The Lakeside Apartments District neighborhood, also known as The Gold Coast, and simply as The Lakeside, is one of Oakland's historic residential neighborhoods between the Downtown district and Lake Merritt. In the context of a Cultural Heritage Survey, the City of Oakland officially named most of the blocks of the neighborhood "The Lakeside Apartments District," and designated it as a local historic district with architecturally significant historic places,[1] and Areas of Primary Importance (APIs). The greater neighborhood includes the interior blocks officially designated as a local historic district and the 'Gold Coast' peripheral areas along Lakeside Drive, 20th Street, and the west edge of Lake Merritt, areas closer to 14th Street and the Civic Center district, and blocks adjacent to downtown along Harrison Street.

Lakeside Apartments District | |

|---|---|

| Nickname: "The Lakeside" "Gold Coast" | |

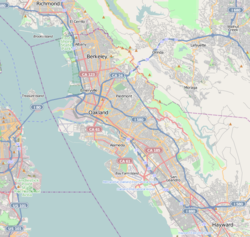

| Coordinates: 37°48′12″N 122°15′51″W / 37.80333°N 122.26417°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| County | Alameda |

| Metro Area | Oakland M.S.A |

| City | Oakland |

| Government | |

| • City Councilmember | Carroll Fife |

| Elevation | 12 ft (4 m) |

| Time zone | UTC-8 (PST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-7 (PDT) |

| ZIP code | 94612 |

| Area code | 510, 341 |

| AC Transit Centers | Downtown Transit Station, Uptown Transit Center |

| AC Transit routes | 26, 1R, 11, 12, 14, 18, 40, 51A, 58L, 72, 72M, 72R, 88; All Nighter Routes 800, 801, 802, 805, 840, 851 |

| BART Stations | 12th Street Oakland City Center, Lake Merritt, 19th Street Oakland |

| BART Lines | R O Y B G |

The district is characterized by a predominance of rent-stabilized apartments, mixed-use buildings, and a long history of regional mass transit connections serving its central location. In recent years, mid-rise, mixed-use, market rate, and affordable rental housing has been planned, proposed, approved, constructed, and inhabited. At the present, other developers have proposed market-rate condominium skyscrapers and other high-rise towers which have idled in various stages of the planning process. From 2007 to 2009, the Oakland Planning Commission revised zoning and building height regulations for the neighborhood.

History

editThe neighborhood was built on what was originally an encinal or Coast Live Oak oak grove on the west shore of the San Antonio Slough, which was later dammed to form Lake Merritt. Prior to the California Mission era, locations around the Slough were fishing and waterfowl hunting grounds for the Ohlone. Later in the Mission era, under the proclaimed authority of his Crown, King Ferdinand VII of Spain deeded the land to Sergeant Luis Maria Peralta in 1820 to become his Rancho San Antonio.

After gold was discovered in 1848 in present-day Coloma 125 miles (201 km) to the northeast, Anglo squatters led by lawyer Horace W. Carpentier took control of the East Bay area which was to become downtown Oakland, including land along the San Antonio Slough.[2]

Before Oakland was even incorporated by the State legislature, by 1850, a trio of three ambitious men, to include Carpentier, had leased land from one of Luis' sons, Vincente Peralta. They hired a Swiss engineer, Julius Kellsburger, to prepare a street grid map. They began selling lots, whether through a good faith belief that US sovereignty superseded Mexican claims, or through deliberate fraud perpetrated on Peralta.[3]

The street grid of Kellsburger's map starts at the Oakland Estuary waterfront, and ends at 14th street, the neighborhood's Southeast boundary. The current streets of the neighborhood show up on E.M. Sessions' 1869 map of Oakland, with long sweeping blocks north of 14th Street. That same year, the western terminus of the transcontinental railroad at Seventh and Broadway brought passengers from New York that had been confined to a train for a week, eager for the comforts and amenities of a city. By this time, horse-drawn streetcars brought passengers up Broadway to 14th Street and points beyond. By the 1890s, the neighborhood had become home to large homes on the lake and interior streets.

By the 1920s, apartment buildings and luxury hotels began to sprout up within walking distance from nearby streetcar lines, and Downtown Oakland.

In the 1960s and 1970s, the neighborhood saw continued development of multi-family, mixed-use apartment buildings with the planning and construction of nearby Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) underground rail lines. Starting in 1961, Oakland's "Downtown Property Owner's Association,"[4] and the "Central Business District Association" repeatedly advocated for extending Alice Street directly through Snow Park, which was then the grounds of the Snow Museum, past the Schilling Gardens and the Bechtel Building, and down to 20th Street to alleviate traffic congestion that might be caused by the closure of Broadway during construction of the nearby BART line underneath Broadway. The plan met stiff opposition from Oakland's City Council in October 1964, and caused then Mayor Houlihan to remark that "One of the things which has bothered me about Oakland is the presence of these small time feuds. The city could be better advanced by using their (downtown businessman's) energies in more progressive ways." As reported by the Staff of the Oakland Tribune at the time, the City Council in essence told downtown business interests to "quit wasting its time."[5]

In the early 21st century, the area continues to be attractive to developers as AC Transit's bus rapid transit lines are currently being planned for 12th and 11th Streets in the neighboring Civic Center district, and on Broadway downtown.

Historic places and landmarks

editThe district has an outstanding concentration of club buildings, historic luxury apartments, and a significant cluster of Deco structures,[6] including the terra cotta Charles Jurgens Co. building, the Elks Hall on Alice Street (now the Malonga Casquelord Arts Center), the Hill Castle Apartments on Jackson Street, The Hotel Harrison on Harrison Street, the Scottish Rite Center at the lake's edge on Lakeside Drive, the Alameda County Courthouse in the neighboring Civic Center district, which also features the Civic Center Post Office on 13th Street. The "Ideal Cleaners" shop features a neon sign and period appointments in the Art Deco style. Many of these historic buildings are protected as official city landmarks.[7][8] During a city Cultural Heritage Survey in the 1980s most of the district was designated as featuring historically significant architectural resources. The Survey was conducted by the city of Oakland's Planning Department and its Landmarks Preservation Advisory Board from 1980 to 1985.[1] Other historic places include the Victorian Camron-Stanford house on the shore of Lake Merritt at 14th Street and Lakeside Drive, the Municipal Boathouse on Lakeside Drive, the Greek revival Scottish Rite Center on Lakeside Drive, the eleven story Bechtel Building at 244 Lakeside, the Alician apartments on Alice Street with its ornate marble entrance, the Regillus condominiums on 19th street, the mission revival Scottish Rite Temple on Madison Street, and the historic Schilling Gardens on 19th Street.

One of the least likely structures to be overlooked—easily visible from a few blocks south of the neighborhood looking up Madison Street, is Tudor Hall. Its distinct architecture resembles the namesake period of the late 15th-early 17th centuries.

The district also features other historic assets in several three- to eight-story apartment buildings, this height being a character-defining feature of most of the historic district. Some exceptions to this character punctuate the neighborhood, to include Noble Tower on Lakeside Drive, and the Essex Condominiums at 17th and Lakeside, completed in 2001.

Parks and community assets

editLakeside park

editThe district is adjacent to Lakeside Park, which lies to the east and northeast of the district. Lakeside Park is a public city park ring and green space surrounding Lake Merritt and is often called the Crown Jewel of Oakland's parks.[9] Lakeside park is historically significant as featuring North America's first official wildlife refuge, designated in 1870. The state legislature voted the Lake Merritt Wildlife Refuge into law in 1870, making it the first such refuge on the North American continent. No hunting of any sort was to be allowed and the only fishing was to be by hook and line.[10][11] Under the name Lake Merritt Wild Duck Refuge, the site became a National Historic Landmark on May 23, 1963.[12][13] It also features a garden center with several cultivated gardens, and the Municipal Boat House on Lakeside Drive. A large restaurant has opened in the Boat House building, which has undergone extensive renovations, and was re-dedicated by city staff in 2009 in anticipation of its re-opening.

Malonga Casquelourd Center for the Arts

editThe neighborhood also features the Malonga Casquelourd Center for the Arts on Alice Street, a public community asset owned and administered by the City of Oakland and its Department of Parks and Recreation.[14] Formerly known as the Alice Arts Center, this building was renamed[15] in 2004 in honor of Malonga Casquelourd, a Congolese dancer, choreographer, singer, percussionist, and cultural ambassador of the arts who was killed in 2003 by a drunk driver traveling in the wrong direction on a blind curve on Lakeside Drive in front of the Essex condominium building.[16] The Alice Arts Center was opened in 1987 under then-Mayor Lionel Wilson. It has a 400-seat theater and fine arts and dance studios where numerous dancers, percussionists, and other musicians study and create music and visual arts. It has become a vibrant center for dance and music, particularly African- and African-American-influenced dance forms from Congolese, Guinean[17] and Afro-Brazilian to jazz and hip-hop. City officials estimate that the center serves 50,000 people a year through classes and performances.[18] The Oakland Ballet has had offices and rehearsals at the center.[19]

The building also features 74 S.R.O. hotel rooms where artists in residence reside. In 2003, then-Mayor Jerry Brown proposed expanding his Oakland School for the Arts, which was at the time housed in the basement and first floor of the Alice Street building, to the entire six-floor center. Numerous hotel rooms were withheld and kept vacant while plans were made to displace the artist tenants from their S.R.O. hotel rooms and studios in the center.[20][21] [22]

The building also features a prominent ground floor retail space adjacent to its main entrance. Over the years the space was the home to a cafe with poetry readings.[23] From late 2003 until early 2007, the space was home to the "Jahva House" cafe, owned by Oakland musician Dwayne Wiggins of the music group Tony! Toni! Toné!. The cafe relocated there following its move from a Lakeshore Avenue space. The cafe featured Wednesday night poetry slams, a traditional African drum craftsman with a sidewalk workshop, and regular live music performances. At present Oakland's Real Estate Division is seeking a retail tenant for the space.

Oakland main library

editThe neighborhood is also walking distance to the Main Branch of the Oakland Public Library on 14th Street between Madison and Oak Street.

Oakland Museum of California

editThe Oakland Museum of California is located at 11th and Oak Streets in the neighboring Civic Center district.

Snow Park

editThe district is also adjacent to Oakland's Snow Park a 4.2-acre (17,000 m2),[24] public city park bordered by 19th Street, the Schilling Gardens Parcel, Harrison Street and Lakeside Drive. Snow Park, which is named after Oakland resident Henry Snow, was once the site of the first Oakland Zoo, the Sidney Snow Zoo, named after Henry Snow's son, which opened in 1943.[25] It currently features public restroom facilities, sitting benches, mature shade trees, a grassy, sunlit meadow, and a golf putting green, which many neighborhood and citywide residents, and nearby office workers enjoy.

Schools and colleges

editResidents of the neighborhood are zoned to schools in the Oakland Unified School District. Zoned schools[26] include Lincoln Elementary School (K-5), which is the local public elementary school.[27] Westlake Middle School, and Oakland Technical High School are the respective intermediate and secondary schools.

Laney College is a public community college located at the south end of the Civic Center neighborhood. Cal State East Bay has the Oakland Professional Development and Conference Center at Broadway and 11th Street. Continuing education courses are offered.

Land development

editThe neighborhood is located between Lake Merritt and Downtown Oakland. In recent years, market-rate housing developers have proposed constructing a variety of residential and residential mixed-use buildings which have been proposed to be anywhere from five to forty-two stories high. Neighborhood residents have voiced their concerns and objections to various proposed developments. Others have pressed developers to include meaningful community benefits to improve proposed projects at "community meetings," and before Oakland's Preliminary Design Review Committee, the City's Planning Commission and City Council.

In recent years Oakland city planning authorities have approved proposed residential mixed use development projects in this neighborhood in part because they are considered by some to be "infill". In other words, they are "filling in" under-utilized "vacant" lots in an urbanized setting. Most all such lots have had daily commercial use such as surface parking for the neighborhood's drive-in workforce by day, and for some of the neighborhood's automobile driving residents and drive-in bar and restaurant patrons by night. One such vacant lot on 14th Street at Madison, directly adjacent to the boundaries of the neighborhood, is used as a preschool playground for several neighborhood children who attend the school, as it is within walking distance for their 'car-free' parents. A developer recently proposed a project for this particular lot which has been tentatively titled "1301 Madison".

Some developers purport that projects proposed for the district's parcels, developed and undeveloped, are substantially exempted from the environmental review provisions of the California Environmental Quality Act(CEQA) because they are considered "infill" parcels. In other words, CEQA has a special provision for streamlined environmental review for infill projects located in urban areas of Oakland. Conversely, some activists have pointed to the applicability of the "Cumulative Impact" provisions of CEQA arguing that the residents of the neighborhood have already been subjected to several consecutive years of construction, dust, pile-driving and general construction noise, and carcinogenic diesel fumes from idling trucks and heavy equipment.

Mid-rise, mixed-use apartment buildings

editAn unfinished building languished in the neighborhood from 2003 to 2009. Originally planned as "Jackson Courtyard Condominiums," the mixed-use building at 1401 Jackson Street features transit oriented development characteristics such as ground-floor retail shop spaces and a dedicated bicycle parking room at street level. For several years, the incomplete project sat partially finished, shrink-wrapped in white plastic sheeting, reminiscent of a condom, hence its local nickname: "Trojan Tower."[28] In September 2008, the shrink-wrap was removed for the second time from the building.[29] In the summer of 2009, after years of extensive reconstruction work, the building finally received its certificate of occupancy and has been replanned for monthly rental apartments. Its first residents began moving into the building in August 2009, a full six years after the original developer of the project broke ground.

In 2008, "Affordable Housing Associates", a Berkeley, California non-profit completed a seven-story, 76-unit apartment building which has been funded in part with affordable housing entitlement funds and pre-development loans from the California Department of Housing and Community Development and the City of Oakland. It includes studio and one-, two- and three-bedroom units that feature a combination of traditional floor plans as well as two-story lofts with flexible layouts. The building features transit-oriented development characteristics to include multiple ground floor retail shop spaces, a transit information kiosk, and 54 parking spaces for 73 units, a ratio of .74 parking spaces per unit, which departs from Oakland's current 'one to one' parking ratio planning law. This project came under intense scrutiny from neighborhood activists for its architectural design which contrasts with the character of a mosque next door to the project, the Islamic Cultural Center of Northern California, a historic mission-revival building that was originally the Scottish Rite masonic temple.[30]

Proposed condominium skyscrapers

edit(a.k.a. "222 19th Street"/"19th Street Residential Condominiums Project") In 2005, a group of land speculators purchased a historic 1920s luxury apartment building at 244 Lakeside Drive on Lake Merritt. The Greenfield land behind the building features the historic Schilling Gardens. The Shilling Gardens is the last remaining portion of a cultivated Japanese garden originally planted in 1886 behind spice magnate August Schilling's Victorian mansion once located on the West shore of Lake Merritt. Today the garden features a shaded grove of several mature Coast Redwood trees, ferns, a sunny lawn area, and hundreds of other cultivated plants laid out into a multi-tiered, brick masonry landscape design, with artistic concrete floral canopy arbors and walking paths. The garden as a whole is considered by the City of Oakland's Register of Historical Resources, and Oakland's Landmarks Preservation Advisory Board, to be a landmark "of highest importance."[31] After purchasing the parcel, the owners divided the parcel into two pieces, one along Lakeside Drive featuring the apartment building, and another parcel behind the building featuring the gardens. The owners then sought to donate the gardens parcel to the City of Oakland in exchange for Historic Preservation property tax credits. Oakland's Real Estate Services Division and Office of Parks and Recreation Staff entered into discussions with the owners. City staff asserted the parcel would need disability accessibility improvements as per the ADA and its own dedicated bathroom facilities, despite bathroom facilities immediately next door at Snow Park. The city staff also insisted the owners pay $760,000 for the aforementioned upgrades, and an additional $178,000 per year, in perpetuity, for ongoing maintenance.

Subsequently, the negotiations fell apart and Oakland's office of Parks and Recreation Director said she didn't bring the decision before the Oakland City Council because she thought that the department dealing with the owner, Oakland's CEDA Real Estate Services Division, was doing that.[31] The director of Oakland Community and Economic Development Agency, Real Estate Services Division denied any responsibility for the missed opportunity. He said he was presented with "budget restraints" and that, in any case, his role was limited to providing "real estate-related expertise.".[31] [32]

In 2006, the owners, two Santa Clara County residents, and a former San Francisco Building Inspection Commissioner, and pari mutuel racehorse owner, proposed a 42-story high-rise condominium skyscraper for the historic Schilling Gardens parcel. They have tentatively labeled the project "Emerald Views" though the official planning documents on file with the city of Oakland refer to the project as "222 19th Street." This parcel is approximately one half block from the lake's current shoreline, at 222 19th Street between Jackson and Alice Streets. Standing at approximately 530 feet (160 m) tall measured from grade to the top of roof spires.,[33] the Emerald Views skyscraper would become the tallest building in Oakland[34] If constructed, the project's architect [35] concedes that "the entire site has to be dug up"[31] and the trees completely destroyed, to construct the new tower, due to its size and extent However, the architect claims the developers intend to replant some of the existing shrubs, plants, and ferns in a new garden area that will abut the sides and back of their proposed building.[31]

While any project on the parcel could diminish the neighborhood's tree canopy, the proposed skyscraper's height and bulk could cast a shadow over a significant portion of Lakeside Park in the afternoons, and the remaining areas of Snow Park that currently receive easterly sunlight every morning, since trees currently shade much of Snow Park.[36] Because of its height, the building would also be anticipated to cast a long shadow over Lake Merritt, Lakeside Park, and the bird sanctuary within Lakeside Park to the east of the parcel. To date the developers have only publicly circulated a sunlight and shadow impact rendering for high noon on the summer solstice, the time of the year with the most sun and the least shadow. The other sunlight and shadow study renderings will be published in the project's upcoming draft Environmental Impact Report (EIR) which may also include hydro-geological issues, air and noise pollution, among other potential environmental impacts.

Former San Francisco Mayor Willie Brown previously owned a 20 percent stake in the Schilling Gardens parcel, but sold out his share to the other owners in 2006 and maintains that he fears that an adjacent high-rise will hurt the value of the building he bought into. Speaking about the project to investigative reporter Phil Matier, Brown claimed in 2006 that "I ain't in that deal."[37]

Since 2006, the owners have assembled a real estate development team led by San Francisco resident Michael Joseph O'Donoghue, more commonly known as Joe O'Donoghue, who is credited with dramatically changing the landscape across the bay in San Francisco through his long history of a variety of lobbying activity for development projects on behalf of the San Francisco Residential Builders Association (RBA).[38] The parcel owners have also retained the services of Oakland's "Go-To-Lobbyist"[39][40] who resigned from his job as a legislative aide to the current Oakland City Council President Ignacio De La Fuente during a time of controversy over conflicts on interest on zoning matters affecting his personal real property portfolio.[41] This former legislative aide's corporation, "Terra Linda Development Services," is an Oakland-based consulting firm which labels itself as "a land development and entitlement consulting company." [42]

In late 2007, the aforementioned "go to" lobbyist was involved in the founding of the "Oakland Builder's Alliance" which purports to achieve its goals "through the promotion and development of innovative policies, through supporting leaders that promote economic growth in Oakland, and through direct organizing in support of leaders and policies that address the needs of our members and the broad building community of Oakland."

On August 8, 2008, the Oakland CEDA Planning and Zoning Division posted Tree Removal Permit Application notices on the gates to the parcel. The gardens feature a grove of several mature Coast Redwood trees that would be completely destroyed by the buildings bulk and mass. This tree removal application is a 'Development Application' regulated by the City of Oakland, and subject to City Council oversight and appeal.[43]

In early 2007, a developer, proposed the construction of a 37-story market-rate condominium skyscraper at 1439 Alice Street, directly across the street from the Malonga Casquelourd Center for the Arts, and adjacent to the three-story 1920s Cliff Apartments. The building would be one of the tallest in Oakland, second only to the Ordway Building in the neighboring Downtown district.[44] The building would be built on a parcel that currently features a combined two story parking garage and retail shop space with an active, longtime retail tenant. The project would maintain the current parking garage facade, with its existing design for the first two levels, with a modern, angular glass tower springing out of the top, and rising to a height of 395 feet (120 m).[45] Though the developer did propose a ground floor wine bar/cold food cafe space for a small portion of the first floor, he proposed an overall reduction in the square footage of the existing ground floor retail space and a substantial square footage for the proposed building resident lobby, and elimination of a current first floor exterior retail space entrance. The developer also proposed a mid-building "wellness center"/"personal services" commercial space. Depending upon a final zoning designation and the planning process however, this commercial space could also be used as medical or professional office or an inclusive, approachable space with a neighborhood-serving retail tenant. Supporters of the Arts Center had concerns that those would move into the building could eventually have a reverse sensitivity to the music and drumming across the street.

Political representation

editThe entire neighborhood lies within the boundaries of Oakland City Council District 3, represented by Carroll Fife, who defeated incumbent Lynette Gibson McElhaney in the 2020 City Council election.

At the county level, the neighborhood lies within Alameda County Board of Supervisors District 5 and is represented by Supervisor Keith Carson.

At the state level, the neighborhood is in the 18th Assembly District, represented by Democrat Mia Bonta, and the 9th Senate District, represented by Democrat Tim Grayson.[46]

Retail

editMost neighborhood restaurants, shops, and services are locally owned and independently operated and enjoy a good business relationship with neighborhood residents who walk to them. Immediately within the neighborhood are small ground floor retail shop spaces which currently feature six grocery and liquor markets, two laundry and dry-cleaner shops, a fabric shop, a tattoo parlor, a gym, a sidewalk cafe one block from Lake Merritt open into the evenings, a pet shop, a diner, a sandwich shop, and two bars. In the fall of 2008, several new ground floor retail shop spaces will be available for lease at two new mixed-use developments on 14th Street in the neighborhood.

Transportation

editMass transit legacy

editIn 1871, Oakland's first horse-drawn streetcar line running down Broadway was not three years old when Hiram Tubbs opened his luxurious "Tubbs Hotel" at Fifth Avenue in what was then "Brooklyn," an independent municipality on the east side of the tidal slough which is now lake Merritt. Tubbs, flush with cash from his hemp cordage business and Comstock Lode silver bullion, wanted his hotel to be the on par with the finest in the state. He spared no expense, investing US$110,000 in 1871 dollars for the building and over US$100,000 more on furniture for the rooms.

Hoping to lure passengers from overland trains, Tubbs had rail laid at his own expense, for his own horse-drawn streetcar line, the "Tubbs Line," to carry passengers from the Train Depot at 7th and Broadway eastward to his hotel. The line went up Broadway to 12th Street, and then down 12th Street through what is now the Civic Center neighborhood, out to 13th Avenue. Tubbs' choice of track routing later evolved into the Oakland Brooklyn and Fruitvale Railroad, and eventually, the "A line" of the Key System of electric streetcars which later ran down 12th and 13th Streets. Today, the 12th Street corridor serves articulated AC Transit buses and is currently being planned for a bus rapid transit line.

In the 1960s, on the Broadway corridor, the BART system was planned and constructed, opening for service in 1972 at three stations, each approximately 1/3 mile from the neighborhood.

Rapid transit

editMany residents in this neighborhood do not own or drive cars and walk to transit connections such as the 12th Street Oakland City Center, 19th Street Oakland, and Lake Merritt BART stations.

Within the neighborhood, AC Transit's 26 line carries passengers to and from the neighborhood along 14th Street, routing directly to nearby BART stations. AC Transit's Uptown Regional Transit Center bus mall on nearby Thomas L. Berkeley Way (20th Street) is now in full farebox service, and features multiple bus shelters with seating, NextBus arrival prediction signs, local and Rapid Bus service to Oakland's streetcar suburbs. These stations host local service, Rapid service, Transbay Express, and All Nighter service. A Translink Add Value Machine is located at AC Transit Headquarters on Franklin Street. The number 1 line running along the neighborhood on 12th Street, between San Leandro and Berkeley, is years into the planning process for the implementation of a full scale bus rapid transit line. The most substantial planning alternative proposed for this system would feature double-articulated buses with five to six doors at boarding platform level, a separated bus-only lane, center median platforms with proof-of-payment ticket machines to speed boarding, and signalization priority to allow bus drivers to change traffic lights in their favor.

Bicycle and pedestrian Facilities

editOther residents use bicycle infrastructure in the area such as the neighborhood's class three Arterial Bike Route: 14th Street, 'BikeLink' bicycle lockers at the nearby 12th Street /City Center, 19th Street, and Lake Merritt BART Stations, and numerous city-installed bike racks to which they can lock their bikes. A Bicycle Rental business rents bikes by the hour nearby on the East side of Downtown. Oakland's Bicycle Master Plan, and Oakland's Measure DD park improvement plan for Lake Merritt calls for an automobile lane reduction and re-striping of bike lanes onto two of the district's streets: Lakeside Drive and Madison Street, and on nearby Webster and Franklin Streets, North of 14th Street. The plan also calls for the installation of a separated class one bikeway and multi-use trail immediately around the perimeter of Lake Merritt, and class two bicycle lanes on all arterial streets surrounding the lake, such as Grand Avenue, between Harrison and Macarthur, where a bike lane already exists, and on Lakeshore Boulevard, onto which a bicycle lane has been planned and contracted to be striped.[needs update]

Taxicabs and carsharing

editAn officially zoned taxicab stand is located at the Northeast corner of 19th and Harrison Streets, next to Snow Park. Automobile taxis are available, and a local bicycle pedicab service is on-call during daytime and early evening hours.

A locally based car sharing service, City CarShare, has a shared car and shared truck at 14th and Jackson, and one car at the Lakehurst Apartment Hotel at 17th and Jackson. An hourly carsharing provider, Zipcar, has three locations in the neighborhood, two cars at 15th and Jackson, and one at 15th and Harrison. A former Zipcar location at 17th and Harrison was removed in early 2008 for environmental scoping on that corner parcel, which has recently been repaved and re-striped for the resumption of parking lot operations. Nonetheless, the lot is currently fenced in anticipation of proposed development on the parcel.

Private vehicle storage

editDue to high demand for parking within the neighborhood, both from a density of residents and from numerous nearby parking "attractors," parts of the streets of the neighborhood have been zoned into Oakland's Area-F Residential Permit Parking (RPP) zone which includes most streets in the neighborhood. This program allows for annual fee-based issuance of one sticker per residence or business from the Parking Enforcement Division of Oakland's Finance and Management Agency. The sticker allows those permit-holders who can find a safe space in the public right-of-way to store a car for three days with exemption from the posted parking restrictions, which are two hours in most areas, reducing cold starts and resulting vehicle emissions.

Violent crime

editCrime and census statistics published by Oakland police and government circa 2017–2020 indicate a lowering of violent crime correlated to Oakland's sustained economic revival, hypergentrification in general, and the influx of affluent residents to the district in particular.[47][48][49]

Nonetheless, property crimes and acts of violence occur periodically, directly within the interior of the neighborhood. The neighborhood lies completely within Oakland's Police Beat 4x, one of 35 across the city. Eleven years ago, in 2009, violent crimes, as reported by the Oakland Police Department, included five burglaries, twelve robberies, and multiple assaults during the summer of 2009.[50]

Oscar Grant murder riots

editIn the days following BART Police Officer Johannes Mehserle's shooting of Oscar Grant on New Year's Morning 2009, and the ensuing reaction by the Alameda County District Attorney's office, justice activists and community members organized response actions and demonstrations. On January 7, about 200 people marched in protest into Oakland's Central Business District. Some became violent and began rioting. Police lines pushed the rioting east from Downtown along 14th Street and into the neighborhood, where rioters continued rioting on Jackson Street and Madison Street. After helicopter-mounted television cameras broadcast images of rioters smashing the windows at a McDonald's restaurant at 14th and Jackson, the rioting briefly wound down after Mayor Ron Dellums and other Oakland leaders came out to the scene to plead with the crowd for calm. Rioters caused over $200,000 in damage while breaking shop and car windows, burning several cars, to include one on Madison Street, setting trash bins on fire, and throwing bottles at police officers.[51][52][53][54][55][56][57] Police arrested over 100.[51][55]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b "Lakeside Apartment Neighborhood Association (LANA)". Archived from the original on 2016-03-08. Retrieved 2008-02-07.

- ^ Northlakegroup.org [https://web.archive.org/web/20070627222546/http://www.northlakegroup.org/LakeMerritt.cfm Archived 2007-06-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Bagwell, Beth (1982). Oakland, Story of a City. Presidio Press. p. 27. ISBN 0-89141-146-1.

- ^ Oakland Tribune Staff (5 April 1963). "Alice Street Extension Plea Renewed". Oakland Tribune Section E17 (printable).

- ^ Oakland Tribune Staff (29 October 1964). "Newest Alice Street Plan Turned Down; Recurring Subject Riles City". Oakland Tribune Section E13 (printable).

- ^ La Tricia Ransom (30 January 2004). "Black artists in spotlight at Richmond Art Center; Show gives novices their first exposure". The San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 25 July 2009.

- ^ Oakland Planning Commission (16 March 2005). "Staff Report" (PDF). Application to designate 1426 Alice Street as a City of Oakland Landmark. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 August 2009.

- ^ Whiting, Sam (23 June 2002). "Gold Coast Redux, Take a drive on Lakeside, Oakland's memory lane". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ "Lake Merritt, The Jewel of Oakland". Oaklandnet.com. Archived from the original on 2008-09-24. Retrieved 2008-09-19.

- ^ "Bay Nature: Loving Lake Merritt". Baynature.org. Retrieved 2008-09-19.

- ^ "Lake Merritt - Wildlife Sanctuary". Oaklandnet.com. Archived from the original on 2006-01-29. Retrieved 2008-09-19.

- ^ McKithan, Cecil (1977-10-18). "Lake Merritt Wild Duck Refuge" (pdf). National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination. National Park Service.

- ^ "Lake Merritt Wild Duck Refuge--Accompanying 4 photos, from 1977" (pdf). National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination. National Park Service. 1977-10-18.

- ^ City of Oakland, Office of Parks and Recreation (7 February 2008). "Malonga Casquelourd Center for the Arts". Official Website. Archived from the original on 5 February 2008.

- ^ Jim Herron Zamora (16 June 2004). "Arts center renaming ceremony scheduled". Official Website.

- ^ The Associated Press (18 June 2003). "Malonga Casquelourd, African Dancer, Dies at 55". New York Times.

- ^ Rick DelVecchio; Chronicle Staff Writer (6 August 2004). "Oakland: A big leap for African dance, drums". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ DeFao, Janine (5 June 2003). "Artists vs. art students in Oakland Mayor wants to use all of Alice Arts Center for arts charter school". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ Murphy, Ann (23 September 2001). "DANCE; Trying to Reflect Oakland's Many Faces". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 October 2008.

- ^ Hackwell, Bill (26 June 2003). "Community fights to save arts center". Workers World. Retrieved 6 October 2003.

- ^ Dance Magazine Staff (1 February 2003). "Lessons learned at Alice Arts Center: art and politics don't mix at new arts-based charter school". Dance Magazine. Retrieved 6 October 2008.

- ^ Dowell, LeiLani (12 June 2003). "Alice Arts Center wins partial victory". Workers World. Archived from the original on 17 May 2008. Retrieved 6 October 2008.

- ^ Millard, Max (21 September 1995). "Black Poetry Readings Weekly In Oakland". Sun Reporter. Archived from the original on 21 October 2012.

- ^ Snow Park, City Of Oakland, Office of Parks and Recreation Archived January 11, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Historic Dates,"City Of Oakland, Office of Parks and Recreation Archived September 27, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "OUSD School-Finder". Mapstacker.ousd.k12.ca.us. Archived from the original on 2008-04-23. Retrieved 2008-09-19.

- ^ Lincoln Elementary School website Archived February 16, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Burt, Cecily (6 June 2008). "Shrink-wrapped buildings have neighbors seeing red". Oakland Tribune.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ Avalos, George (11 September 2008). "Oakland condo project revived". San Jose Mercury News. Retrieved 14 October 2008.

- ^ Burt, Cecily (20 November 2003). "Council approves disputed apartments". Oakland Tribune. Archived from the original on 22 February 2008.

- ^ a b c d e Patterson, Wendy (5 December 2007). "A Wasted Opportunity The city of Oakland botched a chance to save a historic garden near Lake Merritt, where a 42-story condominium is now proposed". East Bay Express. Archived from the original on 5 February 2008.

- ^ Heredia, Chris (13 September 2006). "Councilwoman angry managers didn't tell of garden offer". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ Oakland Community and Economic Development Agency, Planning and Zoning Division. "Project page:"222 19th Street"". Archived from the original on 2008-05-13.

- ^ Heredia, Chris (2007-07-31). "42-story condos sought for lake Developer's high-rise would be the tallest building in city". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ Ian Birchall and Associates (2008-02-07). "Company Website". Archived from the original on 2008-02-05.

- ^ Snow Park, City of Oakland, Office of Parks and Recreation Archived January 11, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Matier, Phillip; Ross, Andrew (10 September 2006). "Heavy hitters square off -- garden or high-rise condos?". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ Sward, Susan (17 July 2000). "The House That Joe Built, How belligerent construction titan has reshaped S.F." San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ Gammon, Robert (9 January 2008). "Meet Oakland's New Go-To Lobbyist". East Bay Express. Archived from the original on 22 February 2008.

- ^ Oakland Public Ethics Commission (30 October 2007). "list of registered lobbyists and their clients as of October 30, 2007". Oakland Public Ethics Commission.

- ^ Harper, Will (23 August 2006). "Nacho's top aide moves into real estate". East Bay Express. Archived from the original on 22 January 2013.

- ^ "Terra Linda Development Services, LLC website". 7 February 2007. Archived from the original on 8 January 2008.

- ^ Public Works Agency, Tree Section (23 September 2008). "Protected Trees Ordinance". City Of Oakland. Retrieved 23 September 2008.

- ^ Burt, Cecily (25 May 2007). "Feedback may foil lakeside high-rise". Oakland Tribune.

- ^ Oakland Planning Department (23 May 2007). "Staff Report, 1439 Alice Street Proposal" (PDF). Oakland City Planning Commission.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Statewide Database". UC Regents. Archived from the original on February 1, 2015. Retrieved November 23, 2014.

- ^ "New Oakland apartments push rents higher than other Bay Area cities". 11 December 2019.

- ^ "Lakeside, Oakland CA - Neighborhood Guide | Trulia".

- ^ "Oakland murders dip to lowest level in 19 years, not everyone impressed". 3 January 2019.

- ^ "CrimeView Community Incident Map". Gismaps.oaklandnet.com. Retrieved 2009-07-23.

- ^ a b Henry K. Lee (10 January 2009). "3 charged in protest over BART shooting". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2009-01-15.

- ^ Matthai Kuruvila; Charles Burress; Demian Bulwa (9 January 2009). "Oakland protest organizer watched in horror". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2009-01-09.

- ^ Dori J. Maynard (2009-01-13). "When is a riot a riot? Did you see what I saw?". San Jose Mercury News. Retrieved 2009-01-14.

- ^ "Oakland: Fewer Businesses Damaged By Protest Than Originally Estimated". KPIX. 2009-01-12.[dead link]

- ^ a b "Grant's family pleads for peace". The San Jose Mercury News. Retrieved 2009-01-08.

- ^ Johnson, Chip (2009-01-09). "Protesters who trashed Oakland missed the mark". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2009-01-11.

- ^ Collins, Terry (2009). "Fatal Calif. train station shooting sparks anger". Associated Press. Retrieved 2009-01-08.[dead link]

Further reading

edit- Bagwell, Elizabeth (1982). Oakland, the Story of a City. Presidio Press. ISBN 0-89141-146-1.

- Evanosky, Dennis; Kos, Eric (2004). East Bay, Then and Now. PRC Publishing. ISBN 1-592-23350-3.