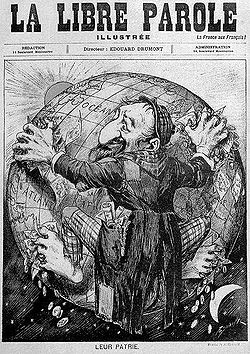

La Libre Parole or La Libre Parole illustrée (French: The Free Speech) was a French antisemitic political newspaper founded in 1892 by journalist and polemicist Édouard Drumont.[1]

| |

| Type | Daily newspaper |

|---|---|

| Owner(s) | Édouard Drumont |

| Founded | April 1892 |

| Political alignment | 1892-1910 Antisemitism Populism Anti-capitalism 1910-1924 Political Catholicism |

| Language | French |

| Ceased publication | June 1924 |

| ISSN | 1256-0294 |

History

editClaiming to adhere to theses close to socialism, La Libre Parole is known for its denunciation of various scandals, including the Panama scandal, which owes its name to the publication of a file about it in Drumont's newspaper.

At the time of the Dreyfus affair, La Libre Parole enjoyed considerable success, becoming the principal organ for Parisian antisemitism. In the aftermath of major Hubert-Joseph Henry's suicide it sponsored a public subscription in favour of the widow in which the donors could express a wish. (A short sample: 0.5 francs "by a cook who would like to put the Jews in her ovens"; 5 francs "by a vicar who ardently wish to exterminate all Jews and Freemasons"; 1 franc "by a little vicar of Poitou who would be happy to sing with joy a Requiem for the last Jew left".)[2] Drumont and his collaborators claimed a link between Jews and capitalism, which shaped the anti-capitalist views of La Libre Parole.

Drumont left the management of the newspaper in 1898 when he made his entry in politics (elected as deputy of Algiers until 1902). Around 1908, wishing to sell La Libre Parole to Léon Daudet, Drumont tried to merge the newspaper with L'Action française, but the project failed.

Following the death of editor Gaston Méry in 1909,[3] Drumont sold La Libre Parole to Joseph Denais in October 1910, who appointed Henri Bazire as new editor-in-chief.[4] The paper became a Catholic organ, close to the Popular Liberal Action and never regained the level of success it had enjoyed with the belligerent style of Drumont. In January 1919, he published a statement by the Marquis de l'Estourbeillon in favour of the teaching of Breton in school.

Antisemitism in France declined during the 1920s, in part because the fact that so many Jews died fighting for France during World War I made it more difficult to accuse them of not being patriotic. La Libre Parole, which had once sold 300,000 copies per issue, closed in 1924.[5]

Legacy

editThe legacy of Drumont's daily newspaper was claimed by several ephemeral publications that reused the title La Libre Parole for nationalist and xenophobic organizations:

- La Libre parole (1er no), later La Libre parole républicaine (Paris, 7 novembre 1926 – avril 1929).

- La Libre Parole de Paris (later Fontainebleau) (1928-1929 [?]) represents itself in 1929 as being the continuation of Drumont's daily newspaper;

1930–1940s : the Libre parole of Henry Coston

edit- La Libre parole, "Monthly review", later "Anti-judeo-masonic review" (Brunoy later Paris, 1930–1936), edited by Henry Coston. In April 1935 it absorbed the biweekly Le Porc-épic (The Porcupine) and then appeared as La Libre parole et le Porc-épic. In October 1937, it was replaced by Le Siècle nouveau, a monthly magazine published by the National Office of Propaganda (Vichy). This Libre parole was published in parallel with the following:

- La Libre Parole, "Independent nationalist body", monthly magazine (Paris, I-III, October 1930–1932), edited by Henry Coston. It also appeared in the same year under the name La Libre parole politique et sociale.

- It later became La Libre parole populaire, "Monthly publication continuing the work of Édouard Drumont" (Paris, I-II, 1933 – November 1934).

- It changed name again to Libres paroles, "Journal de propagande nationaliste" (Paris, December 1934–1935).

- Yet another change to La Libre parole "Journal hebdomadaire" (Paris, September 1935 – April 1939). In 1938, Coston officially took over the volume numbers of Drumont's La Libre parole.

- Algiers deputy candidate Coston renamed his newspaper to La Libre parole d'Alger (later Libre Parole nord-africaine d'Alger et du Nord de l'Afrique), "Anti-jewish weekly of latin action" and sometimes La Parole enchaînée (Alger, avril 1936 – février 1937 and a final issue in 1939). Henry Coston invoked, to justify the cessation of publication, the seizure of publications, leaflets, archives and documents in its offices.[6]

- In 1940, the authorities of Nazi occupied France did not permit the newspaper to reappear. Coston used the title as a publishing label to publish, starting in 1943, the Bulletin d'information anti-maçonnique (Anti-masonic Information Bulletin), and Bulletin d'information sur la question juive (Information Bulletin on the Jewish Question).

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Brustein, William (2003). Roots of Hate: Anti-Semitism in Europe Before the Holocaust. Cambridge University Press. pp. 119–120. ISBN 0521774780.

- ^ R. Girardet, Le nationalisme français. 1871-1914 éd. du Seuil, Paris 1983, pp. 179-181.

- ^ http://revel.unice.fr/revel/pdf.php?id=6&revue=loxias[dead link]

- ^ Prochasson, Christophe (21 November 2013). Les années électriques (1880-1910): Suivi d'une chronologie culturelle détaillée de 1879 à 1911 établie par Véronique Julia (in French). La Découverte. ISBN 978-2-7071-7208-2.

- ^ Jackson, Julian (2001). France: The Dark Years, 1940-1944. Oxford University Press. pp. 105. ISBN 0-19-820706-9.

- ^ André Halimi, La délation sous l'occupation, le cherche midi, p. 70-71