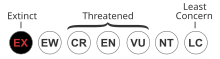

The Lānaʻi hookbill (Dysmorodrepanis munroi) is an extinct species of Hawaiian honeycreeper. It was endemic to the island of Lānaʻi in Hawaiʻi, and was last seen in the southwestern part of the island. George C. Munro collected the only known specimen of this species in 1913, which is housed in the Bernice P. Bishop Museum in Honolulu, and saw the species only twice more, once in 1916 and for a final time in 1918. No other sightings have been reported. They inhabited montane dry forests dominated by ʻakoko (Euphorbia species) and ōpuhe (Touchardia sandwicensis). The Lānaʻi hookbill was monotypic within the genus Dysmorodrepanis and had no known subspecies. Its closest relative is believed to be the ʻōʻū, and some early authors suggested that the Lānaʻi hookbill was merely a deformed ʻōʻū. The Lānaʻi hookbill was a plump, medium-sized bird with greenish olive upperparts and pale whitish yellow underparts. It also had a yellow or white superciliary line and a white chin and throat. The wings also had a distinctive and conspicuous white wing patch. The hookbill's distinguishing characteristic was its heavy, parrotlike bill, which had the mandibles hooking sharply towards each other, leaving a gap between them when the beak was closed.

| Lānaʻi hookbill | |

|---|---|

| |

| Schematic illustration | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Fringillidae |

| Subfamily: | Carduelinae |

| Genus: | †Dysmorodrepanis Perkins, 1919 |

| Species: | †D. munroi

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Dysmorodrepanis munroi Perkins, 1919

| |

| |

| Location of Lānaʻi in the state of Hawaiʻi | |

As the bird became extinct before significant field observations could be made, not much is known about its behavior. The Lānaʻi hookbill is only known to have eaten the fruit of the ōpuhe; however, it is unlikely that its unique bill would have developed to eat fruit, and it may have been a snail specialist. The hookbill has not been seen since 1918, and by 1940 nearly all of Lānaʻi's forests were converted into pineapple fields, destroying the bird's habitat. The combination of habitat destruction and the introduction of feral cats and rats are thought to have led to the Lānaʻi hookbill's extinction.

Taxonomy

editThe Lānaʻi hookbill was first collected by the New Zealand ornithologist George C. Munro from Lānaʻi's Kaiholena Valley on February 22, 1913.[2][3] In 1919 Robert Cyril Layton Perkins described the species as Dysmorodrepanis munroi based upon this specimen, placing the hookbill in a new, monotypic genus.[2] The genus name is derived from the Ancient Greek words dusmoros "ill-fated," and drepanis to identify the species as a Hawaiian honeycreeper. Drepanis comes from the Ancient Greek word drepane "sickle," in reference to most Hawaiian honeycreeper's bills.[4] The specific name munroi recognizes the collector of the specimen, Munro. The common name came from the species' limited range and distinctive bill shape.[4]

However, other taxonomists challenged the validity of the species as early as 1939, noting that the Lānaʻi hookbill was only known from one specimen and arguing that it was merely an aberrant and partially albino female ʻōʻū.[5] The hookbill's validity was not confirmed until 1989 when the specimen's skull was removed and examined. The bird's cranial osteology, myology, plumage, and bill morphology confirmed the distinctness of the species.[3]

The hookbill was a member of the Hawaiian honeycreeper subfamily Drepanididae and the tribe Psittirostrini, which it shared with seven historically recorded species and about ten species known only from fossils.[2] It is believed that the Lānaʻi hookbill was most closely related to the ʻōʻū .[6] No fossil specimens of the Lānaʻi hookbill have been found.[7]

Description

editThe Lānaʻi hookbill was a plump, medium-sized bird.[8] It was about 6 inches (15 cm) in length, and the weight is unknown.[8] It had greenish olive upperparts and pale whitish yellow underparts, as well as a yellow or white superciliary line.[8] The chin and throat were white.[9] The wings' secondaries had a distinctive and conspicuous white wing patch.[8] Due to the subdued colors of the sole specimen, it is believed that it was a female, suggesting that the male would have had a brighter plumage, especially in the superciliary line.[8] The eyes, which were large for a bird of the hookbill's size, were dark brown and the muscular legs were gray with yellow toepads.[10]

The hookbill's distinguishing characteristic was a heavy, parrotlike bill.[8] The upper mandible hooked sharply downwards, while the heavy lower mandible hooked sharply upwards towards the middle of the upper mandible. This structure left a gap between the two mandibles when the bird held its beak closed.[8] It is believed that the bill was pale pink in coloration.[9] The jaw muscles were particularly well developed around the bill.[10] The hookbill's tongue was primitive and nontubular.[3]

Like other Hawaiian honeycreepers, the hookbill possessed a distinctive musty odor.[8] The bird's only known vocalization was an inconspicuous chirp; however, all other Hawaiian honeycreepers are excellent vocalists that demonstrate an array of sounds, and therefore the hookbill likely had a broader, unrecorded repertoire.[11][12]

Distribution and habitat

editThe Lānaʻi hookbill was endemic to the island of Lānaʻi in Hawaii.[7] All recorded sightings of the species were made from the southwestern end of Lānaʻi's forests, which included the Kaiholena Valley and Waiakeakua. These sightings were between 2,000 and 2,600 feet (610 and 790 m) in elevation.[7] However, the species' habitat once covered thousands of acres on Lānaʻi, and it is possible that the species once had a broader range on the island.[6] The species was non-migratory.[6]

It is believed that the Lānaʻi hookbill inhabited montane dry forests on Lānaʻi dominated by ʻakoko (Euphorbia species) and ōpuhe (Touchardia sandwicensis).[13] The unique shape of the hookbill's bill, particularly when compared with the ʻōʻū's bill, and its apparent rarity suggested that the species was an extreme specialist and was therefore restricted to this habitat.[2]

Ecology and behavior

editThe Lānaʻi hookbill is only known to have eaten the fruit of the ōpuhe. The type specimen was caught while feeding on the plant, and its berries were subsequently discovered in its stomach.[6] It is considered likely that the hookbill additionally ate ʻakoko fruits due to their similarity in size and shape to those of the ōpuhe.[6] However, the hookbill's unique bill is considered unlikely to have evolved if the species was purely frugivorous, and it has been suggested that the hookbill specialized in eating snails.[6] The species was very active while searching for food, constantly flying from tree to tree.[14] While perched it shifted restlessly.[10]

Based upon the structure of the bill, it has been suggested that this unique bill was used as a pincer, with the tips of both mandibles touching. The hookbill could have used this movement to pluck fruits or flowers for consumption, or it may have been used to extract snails from their shells.[14] It is also possible that the bird could have crushed a snail shell between its mandibles and then used its tongue to ingest the meat and expel the shell out of the open sides of the beak.[14]

There is no recorded information on the Lānaʻi hookbill's breeding behavior.[15] However, the other Hawaiian honeycreepers are remarkably uniform in their breeding behavior, and it is therefore likely that the hookbills also bred from early winter through the end of summer in August, with pair bonding being completed by January or February.[16] The males likely defended a territory that moved along with his bonded female and became a centered around the nest after the female constructed it.[17] It is hypothesized that the hookbill laid two to three eggs and that its young were altricial.[15]

Extinction

editHistorically, the hookbill was only recorded three times.[2] All three sightings were made by Munro; the first was when he collected a single bird on February 22, 1913, and the other two sightings came on March 16, 1916 and August 12, 1918.[2] The only existing specimen is in the Bernice P. Bishop Museum in Honolulu.[3] The species was not recorded by the native Hawaiians.[4]

The fact that Munro, an excellent observer who spent years on Lānaʻi, only saw the bird three times implies that it was already very rare by the 1910s.[10] From 1900 to 1940 nearly all of Lānaʻi's forests were converted into pineapple fields. This conversion reduced the area of the hookbill's potential habitat, and is believed to be the biggest contributor to the species' extinction.[18] It has also been suggested that avian malaria, which began affecting Lānaʻi's birds in the 1920s, may have contributed to the species' decline.[19] Likewise, the introduction of feral cats and rats to Lānaʻi may have led to a decline in the hookbill's population.[19] The extinction of local snails through human intervention could also have led to the Lānaʻi hookbill's extinction.[3]

References

edit- ^ BirdLife International (2017). "Dysmorodrepanis munroi". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017: e.T22720738A111776369. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-1.RLTS.T22720738A111776369.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Snetsinger 1998, p. 2

- ^ a b c d e James, H. F.; Richard Zusi; S.L. Olson (1989). "Dysmorodrepanis munroi (Fringillidae: Drepanidini), A valid genus and species of Hawaiian Finch" (PDF). The Wilson Bulletin. 101: 159–179.

- ^ a b c Snetsinger 1998, p. 15

- ^ Greenway Jr., James C. (October 1939). "Dysmorodrepanis munroi probably not a valid form" (PDF). The Auk. 56 (4). American Ornithologists' Union: 79–80. doi:10.2307/4078821. JSTOR 4078821. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-08-26.

- ^ a b c d e f Snetsinger 1998, p. 5

- ^ a b c Snetsinger 1998, p. 4

- ^ a b c d e f g h Snetsinger 1998, p. 3

- ^ a b Snetsinger 1998, p. 14

- ^ a b c d Perkins, Robert Cyril Layton (March 1919). "On a new genus and species of bird of the family Drepanididae from the Hawaiian Islands". Annals and Magazine of Natural History. 3 (15). Taylor & Francis: 250–2. doi:10.1080/00222931908673819.

- ^ Snetsinger 1998, p. 8

- ^ Pratt 2010, p. 636

- ^ Snetsinger, Thomas J.; Michelle H. Reynolds; Christina M. Herrmann (1998). "Kona Grosbeak". The Birds of North America Online. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved 2009-02-14.

- ^ a b c Snetsinger 1998, p. 6

- ^ a b Snetsinger 1998, p. 10

- ^ Pratt 2010, p. 640

- ^ Pratt 2010, pp. 640–1

- ^ Snetsinger 1998, p. 13

- ^ a b Snetsinger 1998, p. 11

Cited texts

edit- Pratt, H. Douglas (2010). "Family Drepanididae (Hawaiian Honeycreepers)". In del Hoyo, Josep; Elliott, Andrew; Christie, David (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World. Vol. 15. Weavers to New World Warblers. Barcelona: Lynx Editions.

- Snetsinger, Thomas J.; Reynolds, Michelle H.; Herrmann, Christina M. (1998). "ʻŌʻū (Psittirostra psittacea) and Lānaʻi Hookbill (Dysmorodrepanis munroi)". In Poole, Alan; Gill, Frank (eds.). The Birds of North America. Vol. 335–336. Philadelphia, PA: The Birds of North America, Inc.