The term Kra–Dai peoples or Kra–Dai-speaking peoples refers collectively to the ethnic groups of southern China and Southeast Asia, stretching from Hainan to Northeast India and from southern Sichuan to Laos, Thailand and parts of Vietnam, who not only speak languages belonging to the Kra–Dai language family, but also share similar traditions, culture and ancestry.[note 1]

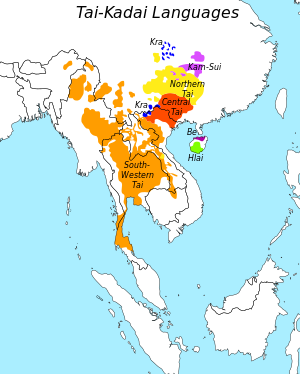

Distribution of the Tai–Kadai (Kra–Dai)–speaking peoples:

| |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| Cambodia, China, India, Laos, Malaysia, Burma, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam | |

| Languages | |

| Kra–Dai languages, Mandarin Chinese (in China) | |

| Religion | |

| Theravada Buddhism, Animism, Shamanism |

Origin

editChamberlain (2016) proposes that the Kra–Dai language family was formed as early as the 12th century BCE in the middle of the Yangtze basin, coinciding roughly with the establishment of the Chu state and the beginning of the Zhou dynasty.[1] Following the southward migrations of Kra and Hlai (Rei/Li) peoples around the 8th century BCE, the Yue (Be-Tai people) started to break away and move to the east coast in the present-day Zhejiang province, in the 6th century BCE, forming the state of Yue and conquering the state of Wu shortly thereafter.[1] According to Chamberlain, Yue people (Be-Tai) began to migrate southwards along the east coast of China to what are now Guangxi, Guizhou and northern Vietnam, after Yue was conquered by Chu around 333 BCE. There the Yue (Be-Tai) formed the Luo Yue, which moved into Lingnan and Annam and then westward into northeastern Laos and Sip Song Chau Tai, and later became the Central-Southwestern Tai, followed by the Xi Ou, which became the Northern Tai).[1]

Tao et. al (2023), however, suggests that the Kra-Dai language family originated from coastal south China, around the Fujian, Guangdong and Guangxi provinces, and underwent a radial expansion into the Guizhou-Yunnan region, Hainan Island, and Mainland Southeast Asia. This language dispersal might also be associated with environmental change and demographic changes.[2]

Kra–Dai peoples are thought to originate from Taiwan, where they spoke a dialect of proto-Austronesian or one of its descendant languages. The Kra–Dai-speaking peoples migrated to southern China, where they brought with them the Proto-Kra–Dai language. Like the Malayo-Polynesians, they may originally have been of Austronesian descent.[3] Unlike the Malayo-Polynesian group who later sailed south to the Philippines and other parts of maritime Southeast Asia, the ancestors of the modern Kra–Dai people sailed west to mainland China and possibly traveled along the Pearl River, where their language greatly changed from other Austronesian languages under the influence of Sino-Tibetan and Hmong–Mien language infusion.[4] However, no archaeological evidence has been identified which would correspond to this Daic expansion in its earliest phases. Aside from linguistic evidence, the connection between Austronesian and Kra–Dai can also be found in some common cultural practices. Roger Blench (2008) demonstrates that dental evulsion, face tattooing, teeth blackening and snake cults are shared between the Taiwanese Austronesians and the Kra–Dai peoples of Southern China.[5][6]

Linguistic subdivisions

editThere are five established branches of the Kra–Dai languages, which may not directly correspond to ethnicity:

- the Tai peoples of China and much of Southeast Asia (including most notably the Thai, Lao, Isan, Shan and Zhuang, and Saek people of Laos and Thailand)

- the Hlai people and Be people of China, especially on Hainan

- the Kra peoples of China and Vietnam (also known as the Geyan peoples)

- the Kam–Sui peoples (which may or not include the Biao people) in central China

The Lakkia people of Guangxi Autonomous Region of China (Tai Lakka in neighboring portions of Vietnam) are ethnically of Yao, but speak a Kra–Dai language called Lakkia.[10] These Yao were likely in an area dominated by Tai speakers and assimilated an early Kra–Dai language (possibly the language of the ancestors of the Biao people).

- The Lingao people in Hainan Province of China speak a Kra–Dai language called Be or Lincheng, although the ethnicity of the Lingao traces back to the Han nationality.[11]

Geographic distribution

editThe Kra-Dai have historically resided in China, continental Southeast Asia and parts of northeastern India since the early Kra-Dai expansion period. Their primary geographic distribution in those countries is roughly in the shape of an arc extending from northeastern India through southern China and down to Southeast Asia. Recent Kra-Dai migrations have brought considerable numbers of Kra-Dai peoples to Japan, Taiwan, Sri Lanka, the United Arab Emirates, Europe, Australia, New Zealand, North America and Argentina as well. The greatest ethnic diversity within the Kra-Dai occurs in China, which is their prehistoric homeland.

The Kra peoples are clustered in the Guangxi, Guizhou, Yunnan, Hunan and Hainan provinces of China, as well as the Hà Giang, Cao Bằng, Lào Cai and Sơn La provinces of Vietnam.

The Kam–Sui peoples are clustered in China as well as neighboring portions of northern Laos and Vietnam.

List of Kra–Dai-speaking peoples per country

editChina

editIn southern China, people speaking Kra-Dai languages are mainly found in Guangxi, Guizhou, Yunnan, Hunan, Guangdong, and Hainan. According to statistics from the fourth census taken in China in 1990, the total population of these groups amounted to 23,262,000. Their distribution is as follows:

- Dai (or Tai) have a population of about 19 million, mainly inhabiting Guangxi, Yunnan, Guangdong and parts of Guizhou and Hunan provinces.

- Kam-Sui (Kam-Shui) have a population of about 4 million and live mainly in Hunan, Guizhou, and in Guangxi.

- Kra have a population of about 22,000 and live mostly in Yunnan, Guangxi and Hunan.

The following is a list of the Kra–Dai ethnic groups in China:

Tai and Rauz peoples

edit- Thai (Central Thai)

- Bouyei

- Tai Chong (Thai: ไทชอง tai chong)

- Dai (Thai: ไทลื้อ tai léu), including the Lu, Han Tai, Huayao Tai and Paxi people

- Tai Dam

- Dong (Chinese: 侗族, Thai: ต้ง), including the Northern and Southern Dong people

- E (Thai: อี๋ ĕe)

- Tai Eolai (Thai: ไทเอวลาย Tai eo laai)

- Fuma (Thai: ฟูมะ Fū ma)

- Hongjin Tai

- White Thai people

- Tai Kaihua (Thai: ไทไขหัว tai kăi hŭa)

- Kang

- Tai Lai (Thai: ไทลาย tai laai)

- Minggiay (Thai: มิงเกีย ming-gia)

- Mo

- Isan people

- Tai Nuea (Thai: ไทเหนือ tai nĕua), including the Tai Mao and Tai Pong people

- Pachen (Thai: ปาเชน bpaa chayn)

- Tai Payee (Thai: ไทปายี่ tai bpaa yêe)

- Pemiayao (Thai: เปเมียว bpay-mia wor)

- Pulachee (Thai: ปูลาจี bpoo-laa jee)

- Pulungchee (Thai: ปูลุงจี bpoo-lung-jee)

- Puyai (Thai: ปู้ใย่ bpôo)

- San Chay (also referred to as the Cao Lan people)

- Shan (Thai: ไทใหญ่ yài tai), including the Cun (Thai: ไทขึน)

- Tay (Thai: โท้)

- Thuchen (Thai: ตูเชน dtoo chayn)

- Thula (Thai: ตุลา dtù-laa)

- Tai Ya people (Thai: ไทหย่า tai yàa)

- Yoy (Thai: ไทย้อย tai yói)

- Tay (including the Tho people)

- Zhuang (Thai: จ้วง jûang), including the Buyang, Dianbao, Pusha, Tulao, Yongchun and Nùng (Thai: ไทนุง) people

Li/Hlai people

editThe Li/Hlai reside primarily, if not completely, within the Hainan Province of China.

Kra peoples

editThe Kra peoples are clustered in the Guangxi, Guizhou, Yunnan, Hunan and Hainan provinces of China, as well as the Hà Giang, Cao Bằng, Lào Cai and Sơn La provinces of Vietnam.

Kam–Sui peoples

edit- Bouyei of Guizhou Province (including Ai-Cham, Mak and T'en, although most Bouyei are nuclear Tai)

- Dong of Guizhou, Hunan and Guangxi Provinces (also referred to as the Kam people)

- Mulao of Guizhou Province

- Maonan of Guangxi Province

- Shui of Guizhou, Yunnan and Guangxi Provinces (also referred to as the Sui people)

Cao Miao people

editThe Cao Miao people of Guizhou, Hunan and Guangxi Provinces speak a Kam–Sui language called Mjiuniang, although it is believed that the people are of Hmong–Mien descent.

Kang people

editThe Kang people of Yunnan Province (referred to as Tai Khang in Laos) speak a Kam–Sui language, but ethnically descend from the Dai people.

Biao people

editThe Biao people are clustered in the Guangdong Province of China.[12]

Lakkia people

editThe Lakkia are an ethnic group clustered in the Guangxi Province of China and neighboring portions of Vietnam, whose members are of Yao descent, but speak a Tai–Kadai language called Lakkia.[10] These Yao were likely in an area dominated by Tai speakers and assimilated an early Tai–Kadai language (possibly the language of the ancestors of the Biao people).

Lingao people

editThe Lingao people are an ethnic group clustered in the Hainan Province of China whose members are classified as Han under China's nationality policy, but speak a Tai–Kadai language called Lincheng.[11]

Laos

editNuclear Tai peoples

edit- Tai Daeng[13]

- Tai Dam[13]

- Tai Gapong

- Tai He

- Tay Khang[13]

- Tai Kao[13]

- Kongsat

- Kuan (Population of 2,500 in Laos)[13]

- Tai Laan

- Tai Maen[13]

- Northern Thai (Lanna)[13]

- Lao (Population of 3,000,000 in Laos)[13]

- Lao Lom[13]

- Tai Long[13]

- Dai (Population of 134,100 in Laos[13] including the Lu people))

- Northeastern Thai (including the Lao Kaleun and Isan people)

- Tai Nuea[13]

- Nùng[13]

- Nyaw

- Tai Pao[13]

- Tai Peung

- Phuan (Population of 106,099 in Laos)[13]

- Phutai (Population of 154,400 in Laos)[13]

- Pu Ko[13]

- Rien[13]

- Tai Sam

- Tayten

- Yoy[13]

- Zhuang (including the Nùng people)

- Shan

- Yang[14]

- Thai (Central Thai)

Kam–Sui peoples

editThe Kam–Sui peoples are clustered in China as well as neighboring portions of northern Laos and Vietnam.

Saek people

editThe center of the Saek population is the Mekong River in central Laos. A smaller Saek community makes its home in the Isan region of northeast Thailand, near the border with Laos.

Thailand

editNuclear Tai peoples

edit- Chiang Saeng

- Central Thai (Thai[15] and Khorat Thai)

- Northern Thai (Tai Wang, Lanna and Thai Yuan)

- Southern Thai (including the Tak Bai Thai people)

- Tai Dam

- Tai Daeng

- Phuan[15]

- Tai Song

- Lao–Phutai

- Lao[15] (Lao Loum, Lao Ga, Lao Lom, Lao Ti, Lao Wiang and Lao Krang)

- Northeastern Thai (Tai Kaleun and Isan)

- Phutai[15]

- Nyaw

- Northwestern Tai

- Tai Bueng

- Tai Gapong

- Khün

- Lao Ngaew

- Nyong

- Yoy

Saek people

editThe center of the Saek population is the Mekong River in central Laos. A smaller Saek community makes its home in the Isan region of northeast Thailand, near the border with Laos.

Vietnam

editNuclear Tai peoples

edit- Buyei

- Tày Tac

- Tai Chong

- Tai Daeng

- Tai Dam[16][17]

- Giáy

- Tai La

- Tsun-Lao

- Tai Kao

- Lao

- Dai

- Tai Man Thanh[16]

- Nang

- Zhuang (including the Nùng people)

- Phutai

- Tai Taosao

- Tay[16] (including the Tho people)

- Tai Do (including the Tay Muoi[16] and Tay Jo people)

- Tai Yung

- Ka Lao

- Thu Lao

- Tai So

- Tai Chiang

- Tai Lai

- Pu Thay[16]

- Tai Hang Thong[16]

- San Chay (also referred to as the Cao Lan people)

- Lu

- Yoy

Kra peoples

editMyanmar

edit- Shan (including the Khamti people)

- Dai (including the Lu people)

- Lao

- Tai Khun

- Tai Yong

- Tai Nuea (including the Tai Mao people)

- Tai Laeng

- Tai Phake

- Thai (Central Thai)

- Tai Piw

- Tenasserim Thai

Cambodia

editIndia

editHistory in China

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2021) |

In China, Kra–Dai peoples and languages are mainly distributed in a radial area from the western edge of Yunnan Province to Guangdong, Guangxi, Guizhou Hunan and Hainan Provinces. Most speakers live in compact communities. Some of them are scattered among the Han Chinese or other ethnic minorities. The ancient Baiyue people, who covered a large area in southern China, were their common ancestors.

The use of name Zhuang for the Zhuang people today first appeared in a book named A History of the Local Administration in Guangxi, written by Fan Chengda during the Southern Song dynasty. From then on, Zhuang would usually be seen in Han Chinese historical books together with Lao. In Guangxi, until the Ming dynasty, the name Zhuang was generally used to refer to those called Li (originating from Wuhu Man) who lived in compact communities in Guigang (the present name), the Mountain Lao in Guilin and the Tho in Qinzhou. According to A History of the Ming Dynasty – Biography of Guangxi Ethnic Minority Hereditary Headman "In Guangxi, most of the people were the Yaos and the Zhuangs, ...the other small groups were too numerous to mention individually." Gu Yanwu (a Chinese scholar in the Ming dynasty) gave the correct explanation of this point, saying "The Yao were Jing Man (aborigines from Hunan), and the Zhuang originated from the ancient Yue."

The word Zhuang was the short form of Buzhuang, which was the name the ancestors of the Zhuang people living in the northeast of Guangxi, the south of Guizhou and the west of Guangdong used to refer to themselves. Later this name was gradually accepted by those who had different names, and finally became the general name for the whole group (Ni Dabai 1990). Zhuang had several variant written forms in the ancient Han historical books.

The Buyi, who lived in Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau since ancient times, were called Luoyue, Pu, Puyue, Yi, Yipu, Lao, Pulao, Yilai, etc., in the Qin and Han dynasties. Since the Yuan dynasty, the name Zhong, which appeared in the historical book later than Zhuang was used to refer to the Buyi. It was originally a variant form of Zhuang, referring to both the Zhuang and the Buyi in Yunnan, Guangxi and Guizhou. Later, it referred to the Buyi only, and always appeared in the historical books as Zhongjia, Zhongmiao, and Qingzhong, until the early 1950s. Like Zhuang, Zhong may also be the short form of Buzhuang, which Zhuang people use to refer to themselves, as the pronunciation of Zhong and Zhuang is similar, and Zhong was once a variant form of Zhuang in the Han Chinese historical books. But today, Buyi people never use Buzhuang or Buzhong to refer to themselves, therefore, the use of Zhong as the name of Buyi may have something to do with the common origin of these two groups of peoples, or the mass migration by Zhuang into Buyi areas (Zhou Guoyan 1996)

Hlai (黎) people living on Hainan island were called Luoyue (雒越) during the western Han dynasty. During the period from the Sui to the Tang dynasty, Li began to appear in the Han historical books. Li (黎) was frequently used in the Song dynasty, and sometimes Lao was also used. Fan Chengda wrote in History of Local Administration in Guangxi: "On the island (Hainan island) there is a Limu Mountain; different groups of aborigines lived around it, calling themselves Li."

The Kam lived in compact communities in neighboring areas across the Guizhou and Hunan Provinces, and Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region until the Ming dynasty. At that time, the name Dong and Dong-Man began to be recorded, In the Qing dynasty, they were called Dong Miao, Dong Min and Dong Jia. Much earlier, during the period of the Qin and the Han dynasty, they were called Wulin Man or Wuxi Man. Later the name Lao, Laohu, and Wuhu were used to refer to a group of people who might be the ancestors of the Kam.

As suggested by some scholars, the ancestors of the Sui were a group of Luoyue (雒越) who were forced to move to the adjacent areas of Guangxi and Guizhou from the Yonjiang River Valley, tracing a path along the Longjiang River because of the chaos of war during the Qin dynasty. The name Sui first appeared in the Ming dynasty. Before that, the Sui had been included in the Baiyue, Man and Lao groups.

The ancestors of the Dai in Yunnan were the Dianyue (滇越) group mentioned in the Records of a Historian by Sima Qian. In Records of the Later Han Dynasty, they were called Shan, and in Records of the Local Countries in Southern China, they were called Dianpu. In the Tang dynasty, they were mentioned as Black Teeth, and as Face-Tattooed in a book named A Survey of the Aborigines by Fan Chuo. These monikers were given based on their customs of tattooing and teeth decoration. In the Song dynasty, they were called Baiyi Man, and in the Yuan dynasty were called Jinchi Baiyi. Until the Ming dynasty, they were generally called Baiyi and after the Qing dynasty, they were called Baiyi. The modern Dai people can be traced back to Dianyue, a subgroup among the ancient Baiyue groups.

Common culture

editThis section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2019) |

Language

editThe languages spoken by the Kra-Dai people are classified as the Kra–Dai language family. The high diversity of Kra–Dai languages in southern China points to the origin of the Kra–Dai language family in southern China. The Tai branch moved south into Southeast Asia only around 1000 AD. These languages are tonal languages, meaning variations in tone of a word can change that word's meaning.

Festivals

editSeveral Kra-Dai groups celebrate a number of common festivals, including a holiday known as Songkran, which originally marked the vernal equinox, but is now celebrated on 13 April every year.

Genetics of Kra–Dai-speaking peoples

editLi (2008)

editThe following table of Y-chromosome DNA haplogroup frequencies of modern Kra-Dai speaking peoples is from Li, et al. (2008).[18]

| Ethnolinguistic group | Language branch | n | C | D* | D1 | F | M | K | O* | O1a*-M119 | O1a2-M50 | O2a*-M95 | O2a1-M88 | O3*-M122 | O3a1-M121 | O3a4[broken anchor]-M7 | O3a5-M134 | O3a5a-M117 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qau (Bijie) | Kra | 13 | 15.4 | 7.7 | 23.1 | 15.4 | 30.8 | 7.7 | |||||||||||

| Blue Gelao (Longlin) | Kra | 30 | 3.3 | 13.3 | 60.0 | 16.7 | 3.3 | 3.3 | |||||||||||

| Lachi | Kra | 30 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 13.3 | 13.3 | 16.7 | 6.7 | 10.0 | 3.3 | 6.7 | 23.3 | |||||||

| Mulao (Majiang) | Kra | 30 | 10.0 | 3.3 | 13.3 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 63.3 | 3.3 | ||||||||||

| Red Gelao (Dafang) | Kra | 31 | 3.2 | 6.5 | 22.6 | 22.6 | 16.1 | 12.9 | 16.1 | ||||||||||

| White Gelao (Malipo) | Kra | 14 | 35.7 | 14.3 | 42.9 | 7.1 | |||||||||||||

| Buyang (Yerong) | Kra | 16 | 62.5 | 6.3 | 18.8 | 12.5 | |||||||||||||

| Paha | Kra | 32 | 3.1 | 6.3 | 6.3 | 9.4 | 3.1 | 71.9 | |||||||||||

| Qabiao | Kra | 25 | 32.0 | 4.0 | 60.0 | 4.0 | |||||||||||||

| Hlai (Qi, Tongza) | Hlai | 34 | 35.3 | 32.4 | 29.4 | 2.9 | |||||||||||||

| Cun | Hlai | 31 | 3.2 | 6.5 | 9.7 | 38.7 | 38.7 | 3.2 | |||||||||||

| Jiamao | Hlai | 27 | 25.9 | 51.9 | 22.2 | ||||||||||||||

| Lingao | Be | 30 | 3.3 | 16.7 | 26.7 | 13.3 | 3.3 | 10.0 | 26.7 | ||||||||||

| E | Northern Tai | 31 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 9.7 | 16.1 | 6.5 | 54.8 | 3.2 | 3.2 | |||||||||

| Zhuang, Northern (Wuming) | Northern Tai | 22 | 13.6 | 4.6 | 72.7 | 4.6 | 4.6 | ||||||||||||

| Zhuang, Southern (Chongzuo) | Central Tai | 15 | 13.3 | 20.0 | 60.0 | 6.7 | |||||||||||||

| Caolan | Central Tai | 30 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 53.3 | 3.3 | 20.0 | 3.3 | |||||||||||

| Biao | Kam–Sui | 34 | 2.9 | 5.9 | 14.7 | 17.7 | 52.9 | 5.9 | |||||||||||

| Lakkia | Kam–Sui | 23 | 4.4 | 52.2 | 4.4 | 8.7 | 26.1 | 4.4 | |||||||||||

| Kam (Sanjiang) | Kam–Sui | 38 | 21.1 | 5.3 | 10.5 | 39.5 | 10.5 | 2.6 | 10.5 | ||||||||||

| Sui (Rongshui) | Kam–Sui | 50 | 8.0 | 10.0 | 18.0 | 44.0 | 20.0 | ||||||||||||

| Mak & Ai-Cham | Kam–Sui | 40 | 2.5 | 87.5 | 5.0 | 2.5 | 2.5 | ||||||||||||

| Mulam | Kam–Sui | 40 | 2.5 | 12.5 | 7.5 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 25.0 | 30.0 | 7.5 | 5.0 | ||||||||

| Maonan | Kam–Sui | 32 | 9.4 | 9.4 | 15.6 | 56.3 | 9.4 | ||||||||||||

| Then | Kam–Sui | 30 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 33.3 | 50.0 | 6.7 | 3.3 | |||||||||||

| Cao Miao | Kam–Sui | 33 | 8.2 | 10.0 | 3.0 | 66.7 | 12.1 |

Full genome analysis

editA 2015 genetic and linguistic analysis showed great genetic homogeneity between Kra-Dai speaking people, suggesting a common ancestry and a large replacement of former non-Kra-Dai groups in Southeast Asia. Kra-Dai populations are closest to southern Chinese and Taiwanese populations.[19]

A 2022 study states that Han Chinese in Fujian and Guangdong provinces show excessive ancestries from Late Neolithic Fujianese sources (35.0–40.3%), which are more significant in modern Ami, Atayal and Kankanaey (66.9–74.3%), and less significant in Han Chinese from Zhejiang (22%), Jiangsu (17%) and Shandong (8%). This suggests a significant genetic contribution from Kra-Dai-speaking peoples, or a peoples related to them, to southern Han Chinese.[20]

Most Kra-Dai-speaking populations in China and Vietnam share connections with the Atayal, with the former harboring about ~3–38% Atayal-related ancestry. They also have Tibetan-related ancestry.[21]

Notes

edit- ^ There is some ambiguity as to the use of the term Tai peoples, as some of the peoples speaking languages in branches of the Kra–Dai language family other than the Tai languages may also call themselves Tai. Therefore the term nuclear Tai peoples is used when discussing speakers of Tai languages.

References

edit- ^ a b c Chamberlain (2016)

- ^ Tao, Yuxin; Wei, Yuancheng; Ge, Jiaqi; et al. (2023). "Phylogenetic evidence reveals early Kra-Dai divergence and dispersal in the late Holocene". Nature Communications. 14 (6924) – via NCBI.

- ^ Sagart 2004, pp. 411–440.

- ^ Blench 2004, p. 12.

- ^ Blench 2009, pp. 4–7.

- ^ Blench 2008, pp. 17–32.

- ^ Blench, Roger (2018). Tai-Kadai and Austronesian Are Related at Multiple Levels and Their Archaeological Interpretation (Draft) – via Academia.edu.

The volume of cognates between Austronesian and Daic, notably in fundamental vocabulary, is such that they must be related. Borrowing can be excluded as an explanation

- ^ Chamberlain (2016), p. 67

- ^ Gerner, Matthias (2014). Project Discussion: The Austro-Tai Hypothesis. The 14th International Symposium on Chinese Languages and Linguistics (IsCLL-14) (PDF). The 14th International Symposium on Chinese Languages and Linguistics (IsCLL -14). p. 158.

- ^ a b Lakkia on Ethnologue

- ^ a b Lingao on Ethnologue

- ^ Biao at Ethnologue

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Ethnologue report for Laos

- ^ The Research and Classification of the Ethnic Groups in Laos[dead link]

- ^ a b c d e The Thai and Other Tai-speaking Peoples

- ^ a b c d e f Thai Ethnic Group in Vietnam

- ^ Vets With a Mission

- ^ Li, Hui, et al. (2008). "Paternal genetic affinity between western Austronesians and Daic populations." BMC Evolutionary Biology 2008, 8:146. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-8-146

- ^ Srithawong, Suparat; Srikummool, Metawee; Pittayaporn, Pittayawat; Ghirotto, Silvia; Chantawannakul, Panuwan; Sun, Jie; Eisenberg, Arthur; Chakraborty, Ranajit; Kutanan, Wibhu (July 2015). "Genetic and linguistic correlation of the Kra-Dai-speaking groups in Thailand". Journal of Human Genetics. 60 (7): 371–380. doi:10.1038/jhg.2015.32. ISSN 1435-232X. PMID 25833471. S2CID 21509343.

- ^ Huang, Xiufeng; Xia, Zi-Yang; Bin, Xiaoyun; He, Guanglin (2022). "Genomic Insights Into the Demographic History of the Southern Chinese". Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution. 10. doi:10.3389/fevo.2022.853391.

- ^ Changmai, Piya; Jaisamut, Kitipong; Kampuansai, Jatupol; et al. (2022). "Indian genetic heritage in Southeast Asian populations". PLOS Genetics. 18 (2): e1010036. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1010036. PMC 8853555. PMID 35176016.

Works cited

edit- Blench, Roger (12 July 2009). "The Prehistory of the Daic (Taikadai) Speaking Peoples and the Hypothesis of an Austronesian Connection" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 April 2019. Retrieved 2 May 2018. Presented at the 12th EURASEAA meeting Leiden, 1–5 September 2008.

- Blench, Roger (2008). The Prehistory of the Daic (Taikadai) Speaking Peoples and the Hypothesis of an Austronesian Connection (PDF). EURASEAA, Leiden, 1–5 September 2008.

- Blench, Roger (2004). Stratification in the peopling of China: how far does the linguistic evidence match genetics and archaeology? (PDF). Human Migrations in Continental East Asia and Taiwan: Genetic, Linguistic and Archaeological Evidence in Geneva, Geneva 10–13 June 2004. Cambridge, England. pp. 1–25. Retrieved 30 October 2018.

- Chamberlain, James R. (2016). "Kra-Dai and the Proto-History of South China and Vietnam". Journal of the Siam Society. 104: 27–77.

- Sagart, Laurent (2004). "The higher phylogeny of Austronesian and the position of Tai–Kadai" (PDF). Oceanic Linguistics. 43 (2): 411–444. doi:10.1353/ol.2005.0012. S2CID 49547647.