Kirk Mill is an early example of an Arkwright-type cotton mill and a grade II listed building in Chipping, Lancashire. Built in the 1780s on the site of a corn mill dating back to at least 1544, it operated as a cotton mill with water frames and then throstles until 1886 when it was sold and repurposed as H.J. Berry's chairmaking factory, powered by a 32 ft (9.8 m) waterwheel, which continued in use, generating electricity until the 1940s.

Kirk Mills wood delivery | |

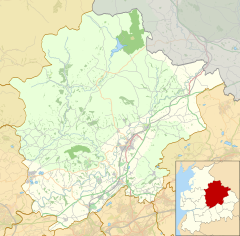

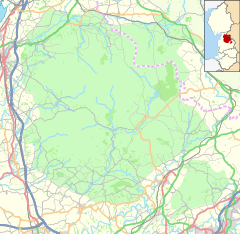

Location in Forest of Bowland | |

| Cotton | |

|---|---|

| Alternative names | Berry's furniture mill Chipping chair works |

| Arkwright-type mill | |

| Architectural style | Stone built three storey |

| Structural system | Stone |

| Location | Chipping, Lancashire, England |

| Coordinates | 53°53′12″N 2°34′43″W / 53.8868°N 2.5785°W |

| Construction | |

| Completed | 1785 |

| Floor count | 3 |

| Water Power | |

| Diameter / width of water wheel | 32 ft / 5 ft |

| Doublers | 1 |

| Other Equipment | Throstles |

Listed Building – Grade II | |

| Official name | Kirk Mill and its associated mill ponds retaining walls, outflow and stone-built leat |

| Designated | 13 May 2011 |

| Reference no. | 1401593 |

Historian Chris Aspin described the historical significance of Kirk Mill, stating, 'To anyone interested in the Lancashire cotton trade, the survival at Chipping of one of the world's first factories is a matter of no little wonder.'[1]

Chipping thrived during the Industrial Revolution when there were seven mills located along Chipping Brook. The last survivor was Kirk Mill, then operating as the chairmaking factory of H.J. Berry. However, in 2010, the company went into administration, the factory closed,[2] and on 7 March 2011, the works were bought by SCPi Bowland Ltd.[3]

Significant refurbishment works including a full re-roof, stone cleaning, re-pointing with lime mortar, removal of incongruous late additions and the introduction of structural steelwork were completed in spring 2017.

Location

editKirk Mill, its 1-acre mill pond behind an embankment, the mill masters mansion Kirk House, the mill manager's house Grove Cottage and the 1823 workhouse are clustered together on the Chipping Brook, a few hundred yards from Chipping Church.[4]

History

editThe original corn mill built on this site was operating in 1544. On the 2 February 1785, Richard Dilworth passed the corn mill to Richard Salisbury of Chipping a cotton manufacturer and William Barrow a merchant of Lancaster, the new mill was functioning by July. On 15 April 1788 the site was offered for sale, and in the advertisement details of its size and equipment were given. The advertised mill, described as 23 by 9 yards, featured a water-wheel of 19.5 by 5.5 feet and was claimed to be in full working condition. It housed 20 spinning frames with 1,032 spindles in operation and had provisions for six additional frames with 48 spindles each. Surrounding facilities included a smithy, barn, three inhabited cottages, one near completion, and four cottages built to the first floor.[5]

Kirk Mill was auctioned again on 25 June 1789 at Preston. The high-bidder was Ellis Houlgrave (1759-1793), the Liverpool-born (later London) clock and watchmaker.[6] On 25 March 1790, Houlgrave insured the mill with the Sun Fire Office for £400, covering the contents for an additional £600.[7] An advertisement in the Manchester Mercury of 6 April 1790, sought ‘about forty hands to work at the branches of carding, roving, spinning, and reeling’.[8] While Houlgrave held the official titles of proprietor and occupier, his father-in-law, the inventor and cotton machinery manufacturer Peter Atherton appears to have played a role in financing and equipping the mill.[9]

The water wheel at Kirk Mill was served by two streams, Chipping (formerly Wolfhouse) Brook[10] and Garstang (now Dobson’s) Brook;[11] however, even this proved insufficient. On 24 June 1792, Houlgrave entered into an agreement with Thomas Weld, owner of the Bowland-with-Leagram and Stonyhurst estates, to dam a third stream (Leagram Brook) and construct a weir and channel. This would divert water from Leagram Brook through one of Weld’s ditches into Dobson’s Brook and then to Kirk Mill. The agreement included the construction of a new corn mill in Chipping. The original corn mill depended on Leagram Brook, which had been damned to redirect water to Kirk Mill. Consequently, after supplying additional power to Kirk Mill, the water then proceeded to a newly established corn mill situated at the edge of the village. It is notable that Houlgrave’s additional water source was located more than a mile from his water wheel at Kirk Mill.[12]

With Houlgrave in failing health, ownership of Kirk Mill passed to his father-in-law Peter Atherton. Short-lived agreements formalised in January 1793 between Atherton and various partners were ultimately superseded by the announcement that from 17 May 1793, Kirk Mill would be carried on by Peter Atherton,William Harrison, and John Rose of Chipping.[13]

Atherton and his partners extended Kirk Mill and turned their attention higher up the valley to Saunder Rake, where they planned a mule mill along with a residence for 150 apprentices.[14] On 11 December 1795, Atherton, Rose, and Harrison insured Kirk Mill. The policy indicated significant business growth since Houlgrave’s insurance more than five and a half years earlier. Although the building figure remained at £400, the millwright’s work and machinery increased from £600 to £4000. Stock was insured for £300. In neighbouring Grove Square, the partners constructed a new building, consisting of stables on the ground floor and a warehouse and reeling rooms above.[15] Grove House was built in the 1790s.

According to the London Gazette, the partnership between Atherton, Harrison, and Rose at Chipping was dissolved on 24 December 1796, and the succeeding partnership between Atherton and Harrison on 11 September 1797. This left Atherton as the sole owner of Kirk Mill until his death in 1799.[16]

It was sold again in 1802, and by then it also housed a 336 spindle mule and an outbuilding suitable for 3 further mules. Mules were more suitable to spinning the softer weft, while water frames of throstles produced a harder twist more suitable for the warp or sewing cotton. An adjoined house that was described as a residence for a genteel family, a further cottage was used as an apprentice house. It is probable that alterations that lengthened the mill were made then. In 1823 Grove Row was constructed as a workhouse, it closed in 1838 and was converted into 5 cottages. One of these cottages served as a shop until 1949.[17] In 1881 the census shows that 10 men, 7 boys and 24 women were employed in the mill.[17]

The cotton mill closed in 1886, and it was acquired by furniture manufacturers. The water wheel stopped being the prime mover in 1923 but drove an electricity generator proving power and light to adjoining houses. Electricity didn't reach the rest of Chipping until 1933. The wheel stopped turning in about 1940, and the top part was cut away to release more space to the mill.[17]

H.J. Berry into administration in 2010, the chair making factory closed.[2] On 7 March 2011 the works were bought by SCPi Bowland Ltd.[3] They are restoring the wheel and the factory and introducing new usages onto the rest of the site.

Arkwright-type mills

editRichard Arkwright was a hard-nosed businessman from Preston. Arkwright produced a continuous spinning machine that was unlike Hargreaves' hand-operated spinning jenny. The jenny required two motions, one to draw and the other to spin and wind. Arkwrights frame spun and wound at the same time and was operated by turning a wheel. The prototype that was powered by hand, was patented in 1769. The process was particular suitable to the application of power which in those times meant a water wheel. Arkwright developed the principle into an industrial machine where a pair of frames would have 96 spindles. In searching for a reliable source of power Arkwright set up his first factory on Cromford, on the River Derwent in Derbyshire. In 1775, he filed a patents for powered preparatory machines that would card and scutch the roving needed by the waterframe. The lantern frame, to draw the roving, and development of the waterframe known as a throstle followed.[18]

Multiple machines were made and placed in one building or factory. The whole process was mechanised; this style of textile production was called the factory system, the operatives had no control on the speed of production or influence on the product, they served the needs of the machines. Arkwright protected his patent and had absolute control over the use of the system. He allowed others to manufacture under licence, but only if they purchased the complete range of machines. To do so they needed plenty of initial capital and a purpose built mill, built mainly to his dimensions with a suitable power source.[18] His patents were revoked in 1785. A watermill required a reliable steady supply of water; while this could be a river that ran at the same velocity throughout the year or a leat running from a river that provided a constant head, but more often a millpond would be built with sluices to regulate the head.

A typical Arkwright type mill was 27 feet (8.2 m) wide internally, which provided space for two 48 spindle frames, while being narrow enough to support the wooden floor beams without the need of a central pillar. The pairs of frames would be placed one per window bay as natural light was the means of illumination. An overhead shaft running the length of the building turned wooded drums at floor level, which by means of leather belts powered the frames. They were built under the supervision of specialist such as Thomas Lowe of Nottingham and John Sutcliffe of Halifax.[19]

The buildings

editKirk Mill in 1788 was 9 yards (8.2 m) by 23 yards (21 m) with a water wheel 19.5 feet (5.9 m) by 5.5 feet (1.7 m). It had 26 spinning frames. By the mill were a smithy, a barn and eight cottages. This was a three-storey fireproof mill: first floor had a height of 8.75 feet (2.67 m), the second of 7.82 feet (2.38 m).[17]

The reservoir holds 1,300,000 imperial gallons (5,900 m3) and is fed by 3 brooks: Wolfhouse (Chipping) Brook, Garstang (Dobson's) Brook and Leagram Brook. The total catchment area is 7.84 km2 (3.03 sq mi).[20] The reservoir was built in 1785, and water passed through a cast iron launder into the mill.

Later use

editThe mill continued to spin cotton using throstles until 1886, when it became a furniture making factory. In 2010 HJ Berry, the furniture manufacturer went into administration and the factory closed. The site was bought by SCPi Bowland Ltd. who have put in detailed planning permission, which includes restoration of the 1785 mill and the waterwheel.[21]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Aspin, Chris (2003). The Water-Spinners. West Yorkshire: Helmshore Local History Society. p. 133. ISBN 0906881110.

- ^ a b Coates, David (16 February 2010). "'Phoenix' hope for HJ Berry factory". Lancashire Evening Post. Johnston Press. Retrieved 1 March 2010.

- ^ a b Kirk Mill, accessed 10 March 2011

- ^ The Water Spinners, Chris Aspin, 2003

- ^ Aspin, Chris (2003). The Water-Spinners. West Yorkshire: Helmshore Local History Society. p. 135. ISBN 0906881110.

- ^ Davies, Ken (2010). "Peter Atherton, Cotton Machinery Manufacturer, 1741-1799". Transactions of the Lancashire and Cheshire Antiquarian Society. 106: 85.

- ^ Aspin, Chris (2002). The Water-Spinners. West Yorkshire: Helmshore Local History Society. p. 135. ISBN 0906881110.

- ^ "Chipping Mill". Manchester Mercury. 6 April 1790.

- ^ Davies, Ken (2010). "Peter Atherton, Cotton Machinery Manufacturer, 1741-1799". Transactions of the Lancashire and Cheshire Antiquarian Society. 106: 85–86.

- ^ Aspin, Chris (2003). The Water-Spinners. West Yorkshire: Helmshore Local History Society. p. 132. ISBN 0906881110.

- ^ Aspin, Chris (2003). The Water-Spinners. West Yorkshire: Helmshore Local History Society. p. 134. ISBN 0906881110.

- ^ Aspin, Chris (2003). The Water-Spinners. West Yorkshire: Helmshore Local History Society. p. 137. ISBN 0906881110.

- ^ Davies, Ken (2010). "Peter Atherton, Cotton Machinery Manufacturer, 1741-1799". Transactions of the Lancashire and Cheshire Antiquarian Society. 106: 86.

- ^ Aspin, Chris (2003). The Water-Spinners. West Yorkshire: Helmshore Local History Society. pp. 137–138. ISBN 0906881110.

- ^ Aspin, Chris (2003). The Water-Spinners. West Yorkshire: Helmshore Local History Society. p. 138. ISBN 0906881110.

- ^ Davies, Ken (2010). "Peter Atherton, Cotton Machinery Manufacturer, 1741-1799". Transactions of the Lancashire and Cheshire Antiquarian Society. 106: 86–87.

- ^ a b c d Dowd, Adrian (4 February 2010). "Proposed Kirk Mill Conservation Area" (PDF). Ribble Valley Borough Council. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

- ^ a b Benson pp 13-14

- ^ Aspin, The Water Spinners, p25

- ^ Inter Hydro Technology Forest of Bowland AONB Hydro Feasibility Study

- ^ Presentation to Parish Council Archived 2012-04-25 at the Wayback Machine, 11 May 2010