Kingston Deverill is a village and civil parish in Wiltshire, England. Its nearest towns are Mere, about 3+1⁄2 miles (6 km) to the southwest, and Warminster, about 5 miles (8 km) to the northeast. The parish and its demographic figures include the village of Monkton Deverill.

| Kingston Deverill | |

|---|---|

Approach to the village and St Mary's church; Whitepits in background | |

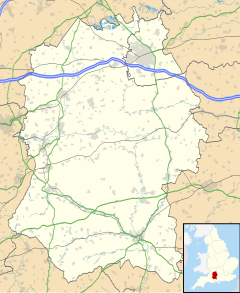

Location within Wiltshire | |

| Population | 248 (in 2011)[1] |

| OS grid reference | ST846371 |

| Unitary authority | |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | WARMINSTER |

| Postcode district | BA12 |

| Dialling code | 01985 |

| Police | Wiltshire |

| Fire | Dorset and Wiltshire |

| Ambulance | South Western |

| UK Parliament | |

| Website | Parish Council |

To the north of the village, under the slope of Cold Kitchen Hill, is the hamlet of Whitepits. The parish is in the Deverill Valley which carries the upper waters of the River Wylye. The six villages of the valley – Kingston, Monkton, Brixton Deverill, Hill Deverill, Longbridge Deverill and Crockerton – are known as the Deverills.

History

editThe area has many bowl barrows, from the Bronze Age or earlier, including one close to the present church.[2] On Whitepits Down is a long linear earthwork from a similar era.[3]

The site of a Romano-Celtic temple on Whitecliff Down in the north of the parish is surrounded by evidence of occupation in the Iron Age and earlier.[4] Two Roman roads crossed at the ford at Kingston Deverill.[5] Near one of those roads, a 1st-century copper alloy pan was discovered by a metal detectorist in 2005. Subsequent excavation by Wessex Archaeology uncovered a pit with two more pans and two copper alloy wine strainers.[6]

A small settlement of nine households was recorded in the Domesday Book of 1086, when the land was held by the canons of Lisieux.[7] Ownership was then taken by the Crown, hence the Kingston prefix.[5] The population of the parish reached 420 at the census of 1841, then declined to 176 in 1901[1] as mechanisation of agriculture reduced employment.[5]

Local government

editUntil 1934, Monkton Deverill was a separate parish.[8]

The parish elects the Upper Deverills Parish Council jointly with neighbouring Brixton Deverill.[9] It falls within the area of the Wiltshire Council unitary authority, which is responsible for all significant local government functions.

Parish church

editThe Church of England parish church of St Mary is from the 15th century. Restoration in 1846 included the rebuilding of the nave, south aisle and chancel. The font is 12th-century.[10][11]

The church was designated as Grade II* listed in 1968.[10] The tower has six bells, cast in 1731 by William Cockey, but they are at present unringable.[12]

The chapelry of Monkton Deverill was transferred to Kingston from Longbridge Deverill in 1892.[13] The small church of King Alfred at Monkton Deverill was made redundant in 1971.[14]

From December 1954 the benefice was held in plurality with that of Brixton Deverill.[15] In 1972 the parish of The Deverills and Horningsham was formed by uniting the parishes of Brixton Deverill, Kingston Deverill with Monkton Deverill, and Longbridge Deverill with Crockerton and Hill Deverill.[16] Today the parish, together with the parish of Corsley and Chapmanslade, is part of the Cley Hill Churches benefice.[17]

Notable buildings

editBesides the parish church, there is a second Grade II* listed building: a timer-framed barn at Manor Farm, formerly thatched, for which tree-ring dating has given a date of 1408–1409.[18][19] Manor farmhouse is a late 18th-century rebuilding, extended in the 19th century.[20]

Kingston House, just below the church, is the former rectory. The 18th-century house was extensively altered in 1858 by the Bath architect G. P. Manners, giving it a ten-window front with many gables.[21] North of the river, Pope's farmhouse was begun in the 16th century.[22]

Notable people

editJohn Howe (1754–1804) was a son of Thomas Howe, rector of Great Wishford and Kingston Deverill. In 1781 he succeeded his uncle Henry as 4th Baron Chedworth. He lived in Suffolk and Norfolk, and seldom visited his extensive landholdings in Gloucestershire and Wiltshire.[23]

The writer, lyricist and ceramicist Lancelot Cayley Shadwell (1882–1963), and his second wife the artist Mary Shadwell, retired to Kingston Deverill[24] in 1937 and lived there until 1957.[citation needed]

References

edit- ^ a b "Wiltshire Community History – Census". Wiltshire Council. Retrieved 16 February 2015. Note ONS raw data encapsulates 'too small to publish all data for reasons of confidentiality of living people' Brixton Deverill in the parish data being here identical to output area E00163628 so more demographic statistics will become available in a few decades from 2011

- ^ Historic England. "Bowl barrow 50m west of St Mary's Church (1010404)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- ^ Historic England. "Linear boundary on Bidcombe Down and Whitepits Down (1016904)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- ^ Historic England. "Romano-Celtic temple and late prehistoric midden (1017314)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- ^ a b c "Kingston Deverill". Wiltshire Community History. Wiltshire Council. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- ^ "Kingston Deverill Hoard". The Salisbury Museum. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- ^ (Kingston) Deveril in the Domesday Book

- ^ "Kingston Deverill". Wiltshire Community History. Wiltshire Council. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- ^ "Upper Deverills Parish Council". Wiltshire Community Web. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- ^ a b Historic England. "Church of St. Mary (1364367)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

- ^ "Church of St. Mary the Virgin, Kingston Deverill". Wiltshire Community History. Wiltshire Council. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

- ^ "Kingston Deverill". Dove's Guide for Church Bell Ringers. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

- ^ "No. 26303". The London Gazette. 1 July 1892. pp. 3794–6.

- ^ "No. 45391". The London Gazette. 8 June 1971. p. 6035.

- ^ "No. 40376". The London Gazette. 4 January 1955. p. 99.

- ^ "No. 45829". The London Gazette. 17 November 1972. p. 13629.

- ^ "St Mary the Virgin Kingston Deverill". Cley Hill Churches. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- ^ Orbach, Julian; Pevsner, Nikolaus; Cherry, Bridget (2021). Wiltshire. The Buildings Of England. New Haven, US and London: Yale University Press. pp. 377–378. ISBN 978-0-300-25120-3. OCLC 1201298091.

- ^ Historic England. "Barn at Manor Farm (1364330)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- ^ Historic England. "Manor Farmhouse (1036405)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- ^ Historic England. "Kingston House (1036402)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- ^ Historic England. "Pope's Farmhouse and Pope's Flat (1036400)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- ^ Blacker, Beaver Henry (1891). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 28. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- ^ CWGC. "Flying Officer Lancelot Rodney Cayley Shadwell | War Casualty Details 2618128". CWGC. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

External links

edit- Upper Deverills Parish Council

- "Kingston Deverill". Wiltshire Community History. Wiltshire Council. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- Kingston Deverill at genuki.org.uk

Media related to Kingston Deverill at Wikimedia Commons