Kenilworth (/ˈkɛnɪlwərθ/ KEN-il-wərth) is a market town and civil parish in the Warwick District of Warwickshire, England, 6 miles (10 km) south-west of Coventry and 5 miles (8 km) north of Warwick. The town lies on Finham Brook, a tributary of the River Sowe, which joins the River Avon 2 miles (3 km) north-east of the town. At the 2021 Census, its population was 22,538.[1] The town is home to the ruins of Kenilworth Castle and Kenilworth Abbey.

| Kenilworth | |

|---|---|

Clock tower at the junction of The Square, Smalley Place and Abbey End | |

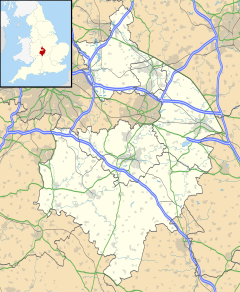

Location within Warwickshire | |

| Population | 22,538 (2021 Census)[1] |

| OS grid reference | SP2971 |

| Civil parish |

|

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | KENILWORTH |

| Postcode district | CV8 |

| Dialling code | 01926 |

| Police | Warwickshire |

| Fire | Warwickshire |

| Ambulance | West Midlands |

| UK Parliament | |

| Website | https://www.kenilworthweb.co.uk/ |

History

editMedieval and Tudor

editA settlement existed at Kenilworth by the time of the 1086 Domesday Book, which records it as Chinewrde.[2]

Geoffrey de Clinton (died 1134) initiated the building of an Augustinian priory in 1122,[3] which coincided with his initiation of Kenilworth Castle.[4] The priory was raised to the rank of an abbey in 1450[3] and suppressed with the Dissolution of the Monasteries in the 1530s. Thereafter, the abbey grounds next to the castle were made common land in exchange for what Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester used to enlarge the castle. Only a few walls and a storage barn of the original abbey survive.

During the Middle Ages, Kenilworth played a significant role in the history of England: Between June and December 1266, as part of the Second Barons' War, Kenilworth Castle underwent a six-month siege, when baronial forces allied to Simon de Montfort, were besieged in the castle by the Royalist forces led by Prince Edward, this is thought to be the longest siege in Medieval English history. Despite numerous efforts at taking the castle, its defences proved impregnable. Whilst the siege was ongoing King Henry III held a Parliament at Kenilworth in August that year, which resulted in the Dictum of Kenilworth; a conciliatory document which set out peace terms to end the conflict between the barons and the monarchy. The barons initially refused to accept, but hunger and disease eventually forced them to surrender, and accept the terms of the Dictum.[5][6]

During the Wars of the Roses in the 15th century, Kenilworth Castle served as an important Lancastrian base in the Midlands: The Lancastrian King Henry VI and his wife, Margaret of Anjou spent much time here.[7]

Elizabeth I visited Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester at Kenilworth Castle several times, the last in 1575. Dudley entertained the Queen with pageants and banquets costing some £1,000 per day that surpassed anything seen in England before.[8][9] These included fireworks.[10]

Near the castle there is a group of thatched cottages called 'Little Virginia': According to local legend they gained this name because the first potatoes brought to England by Sir Walter Raleigh from the New World were planted and grown here in the 16th century. Modern historians however consider this unlikely, and have suggested that the name may have originated from early colonists to America returning to England from Virginia.[11][12]

17th and 18th centuries

editDuring the English Civil War, Kenilworth Castle, was occupied by Parliamentarians, after the Royalist garrison was withdrawn. After the end of the war, the castle's defences were slighted on the orders of Parliament in 1649, after which the castle became a ruin.[5][13]

In 1778 Kenilworth windmill was built. In 1884, it was converted into a water tower, by the addition of a large water tank on the top of the tower in the place of the sails. It continued to be the town's main water supply until 1939, and finally became disused in 1960. It is still a local landmark, but is now a private home.[14]

19th century to present

editWith the demise of the defensive role of the castle, Kenilworth had ceased to be a place of national significance, but Sir Walter Scott's 1821 novel Kenilworth brought it back to public attention, and helped establish the ruins of the castle as a major tourist attraction.[5][15]

In the early 19th century Kenilworth was known for its horn comb making industry, which peaked in the 1830s.[5][16]

Kenilworth was revolutionised by the arrival of the railway to the town in 1844, when the London and Birmingham Railway opened the Coventry to Leamington Line, including Kenilworth railway station. The station was rebuilt in 1884 and a new link line was opened between Kenilworth and Berkswell to bypass Coventry. This closed to all traffic on 3 March 1969.[17] The railway station was located to the south of the Finham Brook valley, and this caused the focus of settlement at Kenilworth to move south, away from the castle, and nearer to the railway station. Industrialists from Birmingham and Coventry arrived, developing the area around the town's railway station with residential and commercial buildings. In the 19th century Kenilworth had some fine large mansions with landscaped gardens; these were demolished after the First World War and Second World War to make way for housing developments. The railway also brought a number of new industries to Kenilworth, such as tanning, brick making, and chemicals, and also caused substantial growth in Kenilworth's market gardening, which became known for producing crops such as tomatoes and strawberries.[15][16]

The town's growth occasioned the addition of a second Church of England parish church, St John's, which is on Warwick Road in Knights Meadow. It was designed by Ewan Christian and built in 1851–1852 as a Gothic Revival building with a south-west bell tower and broach spire.[18] By the 1870s Kenilworth's population had exceeded 4,000.[15]

In 1869, local whitesmith and engineer Edward Langley Fardon demonstrated the first bicycle with wire-spoked wheels and rubber tyres, riding from Warwick Road to Leek Wootton.[19]

During The Blitz in World War II on the night of 21 November 1940, a German aircraft dropped two parachute mines on Kenilworth; the large explosions in the Abbey End area demolished a number of buildings, killing 25 people, and injuring 70 more. The bomb damaged area of the town was redeveloped in the 1960s.[20][5]

In May 1961, the Kenilworth Society was formed over concerns about protecting a group of 17th-century listed cottages adjacent to Finham Brook in Bridge Street.[21] The Society sets out to promote awareness of Kenilworth's character and encourage its preservation.

British Rail withdrew passenger services from the Coventry to Leamington Line and closed Kenilworth Station in January 1965 in line with The Reshaping of British Railways report. In May 1977, British Rail reinstated passenger services, but did not reopen Kenilworth station, which became derelict and was eventually demolished. In 2011 Warwick Council granted John Laing plc planning permission to build a new station,[22] It finally reopened in 2018.[23]

In the early 1980s, the town's name was used by one of the first generation of computer retailers, a company called Kenilworth Computers based near the Clock Tower, for its repackaging of the Nascom microcomputer, with the selling point that it was robust enough to be used by agriculture.[24]

Kenilworth was struck by an F0/T1 tornado on 23 November 1981, as part of the record-breaking nationwide outbreak on that day.[25]

Geography

editKenilworth has several suburbs, including Borrowell, Castle Green, Crackley, Ladyes Hill, Mill End, Park Hill, St Johns, Whitemoor and Windy Arbour. The town has good transport links to Coventry, Warwick, Leamington Spa and Birmingham.[26]

Amenities

editThe principal shopping area of Kenilworth is around Warwick Street, Abbey End and Talisman Square, a 1960s shopping precinct. In 2008, the Square was modernised and partly redeveloped to include a new Waitrose supermarket.[27][28] Kenilworth has been a Fairtrade Town since 2007.[29] The town's public library underwent a renovation in 2021.[30] The Cross, a local pub-restaurant, received a Michelin star in 2015.[31]

Near the centre of Kenilworth is Abbey Fields, a public park which covers 68 acres (28 hectares) within the valley of Finham Brook. Abbey Fields contains the ruins of the historic Kenilworth Abbey as well as St Nicholas Church. It contains public amenities such as a swimming pool, a lake, a children's play area and heritage trails.[32][33] There are several further public open spaces in Kenilworth, including Kenilworth Common, an area of historic common land covering 30 acres (12 hectares).[34][35] Parliament Piece, a field and nature reserve covering 14 acres (5.7 hectares), was where, according to legend, King Henry III held a Parliament in 1266.[36] Knowle Hill Nature Reserve, managed by the Warwickshire Wildlife Trust, is found near the Common and covers 9.7 acres (3.9 hectares).[37]

Landmarks

editIn the centre of Kenilworth stands a Kugel ball water feature, called the Millennium Globe.[38]

Kenilworth's clock tower (pictured at top of article) is an important local landmark. It was first built in 1906–1907 by a notable local benefactor, George Marshall Turner, as a memorial for his late wife. It stands in a roundabout in the town centre. The top part of the tower was severely damaged in 1940 by World War II bombing and had to be pulled down, it was fully restored in the 1970s. The clock tower is locally listed as a heritage asset by Warwick District Council.[39][40]

Governance

editThere are three tiers of local government covering Kenilworth, at parish (town), district and county level: Kenilworth Town Council, Warwick District Council and Warwickshire County Council. The town council is based at Jubilee House on Smalley Place in the town centre.[41]

Kenilworth gained a local board of health in 1877, which was converted into an Urban District Council in 1894.[16] Under local government reforms in 1974 Kenilworth Urban District was merged into the new Warwick District along with Warwick and Leamington Spa. The former urban district of Kenilworth was then reconstituted as a successor parish with a Town (parish) Council.[42]

Since 2010, Kenilworth has been part of the Parliamentary constituency of Kenilworth and Southam; prior to that it was part of Rugby and Kenilworth.

Transport

editKenilworth railway station is situated on the Coventry to Leamington Spa line. The original station was closed in 1965 and later demolished; in April 2018, a new station was opened. West Midlands Trains operates services to Nuneaton, Coventry and Leamington Spa.[43]

Warwick Parkway station is located nearby, which hosts Chiltern Railway services between London Marylebone, Birmingham Snow Hill and Stourbridge Junction.

The A46 bypass opened in June 1974.[44] Both Birmingham Airport and the M6, M42 and M40 motorways are within 12 miles (19 km) of the town.

Media

editLocal news and television programmes are provided by BBC Midlands and ITV Central. Television signals are received from the Sutton Coldfield TV transmitter. [45]

Local radio stations are BBC CWR, Capital Mid-Counties, Hits Radio Coventry & Warwickshire, Fresh (Coventry & Warwickshire), Heart West Midlands, Smooth West Midlands, Greatest Hits Radio Midlands and Radio Abbey, a community based station.[46]

The town is served by two local newspapers, the Kenilworth Weekly News[47] and the Leamington Observer (formerly Kenilworth Observer). [48]

Sport

edit- Kenilworth Town FC, located in Gypsy Lane in the south of the town, played in the Midland Combination until June 2011, when it resigned,[49] preferring to spend money on ground improvements rather than fielding a team. It re-entered the English football pyramid in the 2013–14 season and was placed in the Midland Football League Division 3, the 12th highest tier in the English league system. The stay, however, was brief; the first team again resigned shortly afterwards. The Gypsy Lane ground was purchased in 2018 by Coventry Plumbing F.C., which demolished the clubhouse and built a new one, before starting the 2019–20 season there.[50][51]

- Kenilworth Wardens FC is based at Kenilworth Wardens, a Community Amateur Sports Club in Glasshouse Lane to the east of the town.[52]

- Kenilworth RFC is the town's rugby union club. It fields three senior sides and hosts a large minis, juniors and colts section. The ground is also located in Glasshouse Lane.[53]

- Kenilworth Tennis, Squash and Croquet Club, in Crackley Lane, has nine tennis courts, five squash and racketball courts and two croquet lawns.[54]

- Kenilworth has two cricket clubs: Kenilworth Wardens in Glasshouse Lane fields five senior teams and a juniors section starting from seven years old;[55] Kenilworth Cricket Club fields three senior teams and plays at the Warwick Road ground.[56]

- Kenilworth Runners meets at Kenilworth Sporting in Gypsy Lane. The club caters for runners of all ages and abilities.[57]

- Octavian Droobers is the local orienteering club, using maps of Abbey Fields and Kenilworth Common on which to stage events.

- Kenilworth Wheelers meets all the year round on Saturday and Sunday morning for a road ride. During the summer months, regular evening training rides cater for all abilities from novice to racer.[58]

- Abbey Fields Swimming Pool is in Abbey Fields. It has a 25 m by 10 m indoor pool and an outdoor pool open from May to September. It is home to Kenilworth Swimming Club and Kenilworth Masters Swimming Club.[59]

- Kenilworth Golf Club features a mature 18-hole parkland course, plus a small six-hole par 3 course.[60]

Two Castles Run

editThe Two Castles Run began in 1983 as a fun run between Warwick Castle and Kenilworth Castle.[61] It has grown into an English Athletics-licensed run with 3,000 entrants in 2010.[62] In 2010 and 2011 it held the Warwickshire Amateur Athletic Association 10 Kilometre Championship. In 2012 all 4,000 places were sold within 25 hours. The race is organised each June by Kenilworth Rotary Club[63] in conjunction with the Leamington Cycling and Athletic Club.[64][65]

Arts

editTheatres

editThe Talisman Theatre and Arts Centre, founded as Talisman Players in 1942, moved to its current 156-seat premises in Barrow Road in 1969.[66] It won twelve NODA awards between 2004 and 2018.[67]

The Talisman produces around 9 main stage shows a year including performances from the Talisman Youth Theatre. Since 2022, The Talisman Theatre has been presenting Fringe nights at the Holiday Inn, Kenilworth.[68] The Talisman Theatre also operates a monthly cinema night showing recent films.

Work started in 2022 on a two-phase development of the Talisman Theatre.

The Priory Theatre, founded in 1932 as the Kenilworth Players, uses the former Unitarian/Christadelphian chapel, a Gothic Revival building[3] dating from 1816, which was converted into a 119-seat theatre building in 1945–1946.[69] It was gutted by fire in 1976, but restored and reopened in September 1978.[69]

Kenilworth Arts Festival

editThe first Kenilworth Festival was held in 1935. After a 70-year interval, it was revived locally in 2005. Between 2005 and 2015, events were held almost every year, with varying success.[70] The company became a social enterprise in 2010.[71] In 2015–16, a new team oversaw a change in direction, with a new name, branding and mission statement, as 'Kenilworth Arts Festival'.[72]

Kenilworth Arts Festival took place again on 19–28 September 2019.[73]

Education

editKenilworth is close to the University of Warwick at Gibbet Hill in Coventry 2.5 miles (4.0 km) to the north.

The principal secondary school is the Kenilworth School and Sixth Form. There are also a number of schools for primary age children.

Notable people

editIn order of birth:

- Henry III of England (1207–1272) commissioned the Dictum of Kenilworth, which was made public on 31 October 1266.[74]

- Edward II of England (1284–1327) was held prisoner in Kenilworth Castle in 1326–1327.[75]

- Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester (1532 or 1533–1588) lived at Kenilworth Castle.[76]

- Thomas Underhill (1545–1591) was keeper of the wardrobe at Kenilworth Castle.[citation needed]

- Thomas Hearne (1744–1817), landscape artist, painted The Priory Gate at Kenilworth in 1784.[77]

- William Field (1768–1851), Unitarian minister and local historian, served the Old Meeting House at Kenilworth from about 1830 to 1850.[78]

- Sir Walter Scott's (1771–1832) novel Kenilworth. A Romance appeared anonymously in 1821.[79]

- Samuel Butler (1774–1839), classical scholar and bishop, became the incumbent of Kenilworth in 1802.[80]

- John Sumner (1780–1862), Archbishop of Canterbury, was born in Kenilworth.[81]

- Charles Sumner (1790–1874), religious writer and bishop, was born in Kenilworth.[82]

- William Gresley (1801–1876), religious writer and cleric, was born in Kenilworth.[83]

- Samuel Carter MP (1805–1878), inherited property in Kenilworth and is buried in the graveyard of St Nicholas.[84][85]

- Anna Russell (1807–1876), botanist, lived in Kenilworth.[86]

- Samuel Hawksley Burbury (1831–1911), mathematician, was born in Kenilworth.[87]

- Isabel, Lady Burton (née Arundell, 1831–1896), religious writer and wife of the scholar Richard Francis Burton, was born in Kenilworth.[88]

- George Potter (1832–1893), trade unionist, first president of the Trades Union Congress of England and Wales, was born in Kenilworth.

- Edward Langley Fardon (1839–1926), whitesmith and bicycle innovator, lived in Kenilworth.[89]

- Sir Arthur Sullivan's (1842–1900) long association with vocal music began with a cantata, The Masque at Kenilworth, in 1864.[90]

- Jack Burns (1859–1927), Scottish champion golfer, was instrumental in creating the Kenilworth course in 1890.[91]

- Oliver Bodington (1859–1936), Paris-based international lawyer and marriage broker, was baptised in Kenilworth.[92]

- Edith Emma Cooper (1862–1913), poet, dramatist, diarist and half of the pseudonym Michael Field with Katherine Bradley, was born in Kenilworth.[93]

- Edgar Jepson (1863–1938), writer of crime, adventure and fantasy novels, was born in Kenilworth.[94]

- John Siddeley, Lord Kenilworth (1866–1953), motor and aero engineering pioneer, moved to Crackley Hall, Kenilworth, in 1918.

- Reginald Lee (1870–1913), surviving crew member of the RMS Titanic, died in Kenilworth.[95]

- Alec Issigonis (1906-1988), designer of the Morris Minor and Austin Mini cars, lived and worked in Kenilworth.[citation needed]

- Walter Ritchie (1919–1991), sculptor, lived and worked in Kenilworth.[96]

- Basil Heatley (1933–2019) was a marathon runner and Olympic silver medallist born in Kenilworth.[97]

- Andrew Davies (born 1936), is a novelist and screenwriter who lives in Kenilworth (the 1995 BBC Pride and Prejudice).[98]

- Julia Slingo (born 1950), climate scientist and Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire, was born in Kenilworth.[99]

- Peter Marlow (1952–2016) was a photojournalist and photographer.

- Tim Flowers (born 1967 in Kenilworth) is an Association football goalkeeper, notably for Southampton and Blackburn Rovers. He was capped 11 times by England.[100]

- Rebecca Probert (born 1973), legal historian and expert on marriage law, lives in Kenilworth with her travel-writer husband Liam D'Arcy Brown.[101]

- Kelvin Langmead (born 1985), professional football player for Shrewsbury Town and Northampton Town, was educated at Kenilworth School.[102]

- Sarah-Jane Perry (born 1990), professional international squash player, was educated at Kenilworth School.[103]

Twin towns

editKenilworth is twinned with:

- Bourg-la-Reine, Hauts-de-Seine, France

- Eppstein, Hesse, Germany.

- Roccalumera, Sicily, Italy

Kenilworth also has friendship links with:

- Bo, Sierra Leone, through One World Link (OWL)

- Uyogo, Tanzania

References

edit- ^ a b "Kenilworth". City population. Retrieved 25 October 2022.

- ^ "Warwickshire G-P". The Domesday Book Online. Retrieved 8 September 2021.

- ^ a b c Salzman 1951, pp. 132–143.

- ^ "Kenilworth Castle and Elizabethan Gardens". English Heritage. Retrieved 10 November 2018.

- ^ a b c d e "Getting to know Kenilworth's History!". Visit Kenilworth. 10 June 2021. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- ^ "The Siege of Kenilworth". Our Warwickshire. Retrieved 8 September 2021.

- ^ "Kenilworth Castle: Chapter 4 : Lancastrian Stronghold". Tudor Times. Retrieved 13 September 2021.

- ^ Information about Elizabethan masques Archived 21 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Shepherd, Marc (24 December 2003). "Kenilworth (1864)". Gilbert & Sullivan Discography. Archived from the original on 25 June 2008.

- ^ Langham, Robert (1580). Langham letter.

- ^ "Raleigh's Potato Patch". Victorian kenilworth. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- ^ "Little Virginia in Kenilworth". Our Warwickshire. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- ^ "Kenilworth Castle: Phase 3". Our Warwickshire. Retrieved 8 September 2021.

- ^ "Kenilworth Windmill". Our Warwickshire. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- ^ a b c "History of Kenilworthl". Kenilworth Town Council. Retrieved 11 September 2021.

- ^ a b c "Parishes: Kenilworth". British History Online. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- ^ Warwickshire Railways – Kenilworth JunctionWarwickshire Railways website article; Retrieved 3 September 2013

- ^ Pevsner & Wedgwood 1966, p. 319.

- ^ Harringman, Harmer & Harmer (2018). The Fardons of Gloucestershire. Self published. pp. 43–45.

- ^ "The war comes to Kenilworth". Victorian Kenilworth. Archived from the original on 7 September 2021. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- ^ "The Kenilworth Society". Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ "Planning Application WDC/10CC067". Warwickshire County Council. Retrieved 14 September 2011.

- ^ "Green light for Kenilworth station". Press release. Department for Transport. 12 December 2013. Retrieved 13 December 2013.

- ^ http://www.nascomhomepage.com/pdf/Kenilworth_case.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ European Severe Weather Dabase Retrieved 10 November 2018.

- ^ OS Explorer Map 221, Coventry & Warwick ISBN 978-0-319-24414-2

- ^ "Supermarkets and Talisman Square". Victorian Kenilworth. Archived from the original on 10 September 2021. Retrieved 10 September 2021.

- ^ "Warwickshire gets its first Waitrose". Coventry Telegraph. 31 July 2008. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- ^ "Everything you need to know about Fairtrade in Kenilworth". Kenilworth Nub News. 16 September 2020. Retrieved 12 September 2021.

- ^ "Home News Local News Kenilworth Library to receive complete refurbishment for first time in 15 years". Kenilworth Nub News. Retrieved 12 September 2021.

- ^ "Top Kenilworth restaurant retains Michelin star". The Leamington Courier. 2 October 2018. Retrieved 12 September 2021.

- ^ "Abbey Fields". Kenilworth Town Council. Retrieved 11 September 2021.

- ^ "Abbey Fields". Visit kenilworth. Retrieved 11 September 2021.

- ^ "Kenilworth Common". Warwickshire Wildlife Trust. Retrieved 12 September 2021.

- ^ "Kenilworth Common". Visit Kenilworth. Retrieved 12 September 2021.

- ^ "Parliament Piece Becomes Nature Reserve". CWN. Retrieved 12 September 2021.

- ^ "Knowle Hill". Warwickshire Wildlife Trust. Retrieved 14 August 2022.

- ^ Snoeijer, Jacco H. "Physics of the granite sphere fountain" (PDF). American Associate of Physics Teachers. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 April 2018. Retrieved 19 November 2016.

- ^ "The Local List of Heritage Assets" (PDF). Warwick District Council. Retrieved 12 September 2021.

- ^ "Kenilworth Clock Tower". Visit Kenilworth. Retrieved 31 October 2021.

- ^ "Kenilworth Town Council". Retrieved 17 June 2023.

- ^ "History Of Kenilworth". Kenilworth Town Council. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- ^ "May Timetable Changes". West Midlands Railway. Retrieved 14 June 2019.

- ^ "Derek, 93, gets award of merit". Kenilworth Weekly News. Johnston Publishing Ltd. 31 May 2007. Archived from the original on 25 March 2018.

- ^ "Sutton Coldfield (Birmingham, England) Full Freeview transmitter". UK Free TV. 1 May 2004. Retrieved 24 December 2023.

- ^ "Radio Abbey". The Kenilworth Centre. Retrieved 24 December 2023.

- ^ "Kenilworth Weekly News". British Papers. 17 January 2014. Retrieved 24 December 2023.

- ^ "Kenilworth Observer (defunct)". British Papers. 31 December 2010. Retrieved 24 December 2023.

- ^ "Kenilworth Pull Out Of Midland Comb". Pitch Hero Non-League. 6 June 2011.

- ^ "'We're bringing football back' say soon-to-be owners of old Kenilworth Town FC land". Kenilworth Weekly News. 10 September 2018.

- ^ "Directory". Midland Football League. Archived from the original on 18 February 2020. Retrieved 18 February 2020.

- ^ "Kenilworth Wardens". Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ "Kenilworth RFC". Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ "Kenilworth Tennis Club". Archived from the original on 14 January 2012. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ "Kenilworth Wardens". Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ "Kenilworth Cricket Club". Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ "Kenilworth Runners". Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ "Kenilworth Wheelers". Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ "Kenilworth Masters". Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ "Kenilworth Golf Club". Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ Rotary Club of Kenilworth Retrieved 10 November 2018.

- ^ English Athletics.

- ^ Kenilworth Rotary Club.

- ^ Leamington Cycling and Athletic Club.

- ^ Two Castles Run.

- ^ "About us". Talisman Theatre and Arts Centre. 4 December 2022. Retrieved 13 February 2023.

- ^ "Archive". Talisman Theatre and Arts Centre. Retrieved 13 February 2023.

- ^ Smith, James (31 March 2022). "Kenilworth theatre announces new monthly fringe night". Kenilworth Nub News. Retrieved 24 March 2023.

- ^ a b "History". About Us. Priory Theatre. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- ^ "Kenilworth Festival makes comeback". Kenilworth Weekly News. 11 February 2008.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Telegraph, Coventry (16 May 2011). "Kenilworth Festival 2011 comes to successful end (Pictures)". Coventry Telegraph. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ "Kenilworth Arts Festival". Visit Kenilworth. Retrieved 3 May 2022.

- ^ Retrieved 18 February 2020.

- ^ Rothwell, H., ed. (1975), English Historical Documents III, 1189–1327, London, p. 380.

- ^ J. R. S. Phillips, "Edward II (1284–1327)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography accessed 18 April 2014

- ^ Haynes, Alan (1992): Invisible Power: The Elizabethan Secret Services 1570–1603, p. 12.

- ^ Retrieved 18 April 2014.

- ^ "Field, William". Dictionary of National Biography. London, 1885–1900.

- ^ British Library catalogue. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.) Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Edward J. Davies, "Some Connections of the Birds of Warwickshire", The Genealogist, 26 (2012): pp. 58–76.

- ^ "Ridley, William Henry". Dictionary of National Biography. London, 1885–1900.

- ^ Goodwin, Gordon (1890). "Gresley, William". In Stephen, Leslie; Lee, Sidney. Dictionary of National Biography 23. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 153–55.

- ^ "Samuel Carter". Dictionary of Unitarian and Universalist Biography. Archived from the original on 20 March 2018. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ "Carter, Samuel". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/49346. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Creese, Mary R. S. (2000). Ladies in the Laboratory? American and British Women in Science, 1800–1900: A Survey of Their Contributions to Research. Scarecrow Press. pp. 31–32. ISBN 9780585276847.

- ^ "Burbury, Samuel Hawksley". Dictionary of National Biography, 1912 suppl. London.

- ^ Lovell, Mary S., A Rage to Live, W. W. Norton, 1998.

- ^ Leach, Robin D. (2011). Kenilworth People and Places, Volume I. Rookfield Publications. pp. 62–66. ISBN 978-0-9552646-1-0.

- ^ Robin Gordon-Powell (Archivist & music librarian of the Sir Arthur Sullivan Society), Preface to score of Kenilworth, London, 2002.

- ^ "Club History". Kenilworth Golf Club. Retrieved 27 September 2013..

- ^ Joseph Foster: Men-at-the-Bar (1885), p. 42.

- ^ White, Chris (1992), "'Poets and Lovers Evermore': The poetry and journals of Michael Field", in Bristow, Joseph (ed.), Sexual Sameness: Textual Differences in Lesbian and Gay Writing, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-06937-8

- ^ "Edgar Jepson, 74, English Novelist". The New York Times (Wireless to The New York Times), 12 April 1938, p. 23.

- ^ Mr Reginald Robinson Lee – Titanic Biography – Encyclopedia Titanica at www.encyclopedia-titanica.org

- ^ Rogers, Byron, The Arts: Sculpture – do's and don'ts Walter Ritchie's career...The Sunday Telegraph 12 May 1996.

- ^ HeroID=5150 Sporting Heroes www.sporting-heroes.net

- ^ Ive-a-monstrous-ego-to-keep-in-check accessed 16 November 2019.

- ^ "Slingo, Prof. Julia Mary". Who's Who 2014, A & C Black, 2014.

- ^ Soccer Base stats player_id=2562 www.soccerbase.com accessed 28 November 2014.

- ^ Professor Probert's Warwick University webpage warwick.ac.uk accessed 21 August 2023

- ^ Squashinfo www.skysports.com accessed 21 August 2023

- ^ Squashinfo. Sarah-Jane Perry accessed 18 April 2014.

Sources

edit- Pevsner, Nikolaus; Wedgwood, Alexandra (1966). Warwickshire. The Buildings of England. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. pp. 317–326.

- Salzman, LF, ed. (1951). "Kenilworth". A History of the County of Warwick. Victoria County History. Vol. 6: Knightlow hundred. London: Oxford University Press for the Institute of Historical Research. pp. 132–143.

External links

edit- Kenilworth Town Council

- Kenilworth The Best Kept Secret in Warwickshire — official Kenilworth town centre website

- Kenilworth Chamber of Trade

- Geograph photos of Kenilworth and surrounding area

- Kenilworth local history articles and books

- Kenilworth in the Second World War

- Catalogue of the Kenilworth Urban District Council archives held at the Modern Records Centre, University of Warwick

- Warwickshire Geological Conservation Group (WGCG) is based in Kenilworth

- Kenilworth archives – Our Warwickshire