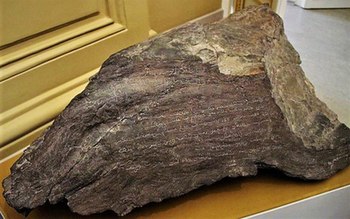

The Karsakpay inscription (also called the Timur's stone)[1] is a message carved on April 28, 1391[2] into a fragment of rock in Ulu Tagh mountainside near the Karsakpay mines, Kazakhstan. It was found in 1935.[2][3] It consists of three lines in Arabic, and eight lines in Chagatai, written in the Old Uyghur alphabet.[4]

After its discovery, the Karsakpay inscription was taken to the Hermitage Museum in Leningrad (now Saint Petersburg) in 1936,[2] where it is today.[5][6] The inscription mentions how Timur is asking to those reading the inscription to remember him with a prayer.[7]

The inscription was researched and published by Nicholas Poppe in 1940, and later researched by Napil Bazilhan, Hasan Eren, Olga Borisovna Frolova, A. P. Grigoryev, N.N. Telitsyn, A.N. Ponomarev and Zeki Velidi Togan.[3]

Measurements

editThe inscription measures 80x40 centimeters. The depth of the carvings are within 1.5–2 millimeters. The distance between Arabic and Chagatai lines are 18 centimeters.[2]

Description

editThe inscription notes the crossing of Timur, a Turco-Mongol conqueror, and his 200,000 men in pursuit of campaign against Tokhtamysh, a ruler of the Golden Horde from 1378 to 1395, and the route that passed through the semi-desert regions of Betpak-Dala.[6]

In Zafarnama (Book of Victories), written in the first quarter of the 15th century, its author Sharaf ad-Din Ali Yazdi gives one historical event of that campaign:

For a joyful survey of that steppe, Timur ascended to the top of the mountain, the whole plain was all green. He stayed there that day, (then) a high order came out, so that the soldiers brought stones and a high sign, like a lighthouse was put in that place. Master stonecutters inscribed on it the date of that day, so that to leave the reminder on the face of time.[8]

Complete text

editArabic

editArabic transliteration: (by the International Turkic Academy)[3]

|

Translation:[9]

|

Chagatai

edit|

Chagatai transliteration:[10]

|

Translation:[10]

|

Chagatai transliteration: (by International Turkic Academy)[3]

|

References

edit- ^ Fomin, V. N.; Usmanova, E.R.; Zhumashev, R.M.; Pokussayev, A.V.; Motuza, G.; Omarov, Kh.B.; Kim, Yu.Yu.; Ishmuratova, M.Yu. (2018). "Chemical-technological analysis of slags from the "Altynshoky" complex" (PDF). Химия (Chemistry). 91 (3): 1. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ^ a b c d Ponomarev, A. I. (1945). "ПОПРАВКИ К ЧТЕНИЮ "НАДПИСИ ТИМУРА" (Amendments to the Readings of Timor's inscriptions" (PDF). Советское востоковедение (Soviet Oriental Studies) (in Russian). 3. Moscow: Academy of Sciences of USSR: 222–224.

- ^ a b c d "Emir Temir'in Yazıtı (Karsakpay //Аltın Şokı anıtı), 1391. Karsakpay Anıtı. Petersburg, Devlet Ermitaj Sergisi Karsakpay Anıtı. N.N.Poppe". 2 October 2020.

- ^ Grigoryev, A. P. (2004). Historiography and source study of the history of the countries of Asia and Africa. pp. 3–24.

- ^ Trever, Kamilla Vasilyevna; Yakubovskiy, A.Y.; Voronets, M.E. (1947). История народов Узбекистана (History of the Peoples of Uzbekistan) (in Russian). Vol. 2. Moscow: Тревер. p. 355. ISBN 978-5-458-44514-6.} (registration required)

- ^ a b Allworth, Edward (1990). The modern Uzbeks: from the fourteenth century to the present: a cultural history. Stanford: Hoover Institution Press. p. 215. ISBN 9780817987329.

- ^ Brummell, Paul (2008). Kazakhstan. Chalfont St. Peter, UK: Bradt Travel Guides. p. 203. OCLC 263068377.

- ^ Tizengauzen, V.G. (1941). Сборник материалов, относящихся к истории Золотой орды (Collection of materials related to the history of the Golden Horde) (in Russian). Vol. 2. Moscow; Leningrad: Academy of Sciences of the Soviet Union.

- ^ "Altynshoky". 6 November 2020.

- ^ a b "A mysterious stone of Timur". Silk Roads World Heritage. 2016. Retrieved 2 October 2020.