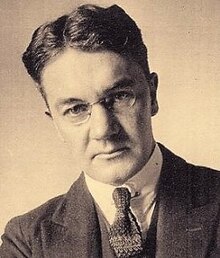

Julius Allan Greenway Harrison (26 March 1885 – 5 April 1963) was an English composer and conductor who was particularly known for his interpretation of operatic works. Born in Lower Mitton, Stourport in Worcestershire, by the age of 16 he was already an established musician. His career included a directorship of opera at the Royal Academy of Music where he was a professor of composition, a position as répétiteur at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, conductor for the British National Opera Company, military service as an officer in the Royal Flying Corps, and founder member and vice-president of the Elgar Society.[1]

Life and career

editEarly years

editHarrison was born in 1885 in Lower Mitton, Stourport in Worcestershire.[2] He was the eldest of four sons and three daughters of Walter Henry Harrison a grocer and candle maker from the village of Powick near Malvern,[3] and his wife, Henriette Julien née Schoeller, a German-born former governess.[2] He was educated at a dame school in Stourport,[3] and at Queen Elizabeth's Grammar School, Hartlebury.[2] The family was musical; Walter Harrison was conductor of the Stourport Glee Union, and Henriette was Julius's first piano teacher. He later took organ and violin lessons from the organist of Wilden parish church, and sang in the church choir.[2]

At the age of 16 Harrison was appointed organist and choirmaster at Areley Kings Church, and at Hartlebury Church at the age of 21.[3] When he was 17 he directed the Worcester Musical Society in a performance of his own Ballade for Strings.[3] He gained two Firsts in music in Cambridge local examinations, and studied under Granville Bantock at the Birmingham and Midland Institute of Music where he specialised in conducting.[1][3]

He first came to wider public notice in 1908 with his setting of Gerald Cumberland's cantata libretto Cleopatra.[4][5] Harrison's setting won the first prize at the Norwich Musical Festival, adjudicated by Frederick Delius, Samuel Coleridge-Taylor and Ernest Walker.[4][6][7] The Times commented on the inadequacy of the libretto, and praised Harrison's orchestration and melodies but complained that the work was "a series of pictures of unbridled passion devoid of all that ordinary people call beauty."[8] The reviewer in The Manchester Guardian was more complimentary; though he commented on the obvious influence of Bantock, and over-elaborate orchestration, he wrote that Harrison had undoubted talent.[6]

Moving to London when he was 23,[3] he took a job with the Orchestrelle Company, a manufacturer of rolls for player-pianos.[2] He conducted amateur ensembles and was organist of the Union Chapel, Islington. In the latter capacity he wrote several pieces for the choir during 1910 and 1911, and his symphonic poem Night on the Mountains was played at the Queen's Hall by the London Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Harrison at the invitation of Hans Richter.[2] The Times said, "The orchestral colouring is laid on with so thick a brush that the outlines get somewhat obscured in places, but it still contains some promising ideas".[9]

Conducting and later career

editFor most of his career Harrison was obliged to earn a living by conducting and other musical work, to the detriment of his composing.[2] In early 1913 he was engaged as a répétiteur at Covent Garden, where he had the opportunity of observing Arthur Nikisch prepare Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen. Later that year Harrison was appointed to the conducting staff for the season.[2] In 1914 he was assistant conductor to Nikisch and Felix Weingartner in Paris, rehearsing Parsifal for the former and Tristan und Isolde for the latter.[2]

In 1915 Thomas Beecham and Robert Courtneidge presented a season of opera at the Shaftesbury Theatre. Harrison was recruited as a conductor along with Percy Pitt, Hamish MacCunn and Landon Ronald.[10] After a second season with Courtneidge, Beecham set up on his own account in 1916, and established the Beecham Opera Company at the Aldwych Theatre of which his father Sir Joseph Beecham was the lessee.[11] Harrison, Pitt, and Eugene Goossens joined him as assistant conductors.[11] In 1916 Harrison joined the Royal Flying Corps and was commissioned as a lieutenant in the technical branch. He was based in London, and was frequently able to conduct for Beecham, often wearing his uniform.[12]

From 1920 to 1923 Harrison was co-conductor of the Scottish Orchestra with Ronald, and from 1920 to 1927 he was also in charge of the Bradford Permanent Orchestra.[2] From 1922 to 1924 he was a conductor for the British National Opera Company, specialising in Wagner.[2]

In 1924 Harrison left the opera company and took up an appointment at the Royal Academy of Music where he was director of opera and professor of composition until 1929.[2] He returned to conducting in 1930 as conductor of the Hastings Municipal Orchestra, running an annual festival and, during the summer season, conducting up to twelve concerts a week. He raised the standard of the orchestra to challenge that of its south-coast rival, the Bournemouth Municipal Orchestra.[13] He secured the services of guest artists including the conductors Sir Henry Wood and Adrian Boult, pianists such as Clifford Curzon and Benno Moiseiwitsch and singers including George Baker. He presented concert performances of neglected works such as Sullivan's and German's The Emerald Isle.[14] After the outbreak of the Second World War the Hastings orchestra was disbanded. From 1940 to 1942 Harrison was director of music at Malvern College. He then accepted a post as a conductor with the BBC Northern Orchestra in Manchester.[2]

The onset of deafness forced Harrison to give up conducting. He had been closely associated with the Elgar Festival in Malvern, and his last appearance on the podium was at the final concert of the 1947 festival.[2] He was a founder member and vice-president of the Elgar Society.[15]

Harrison died in 1963, aged 78, in Harpenden in Hertfordshire (at The Greenwood, Ox Lane) where he settled after leaving Malvern towards the end of the 1940s.[16][17]

Works

editMusic

editAlthough he had to focus mainly on conducting as his source of income,[2] Harrison was a fairly prolific composer, beginning in his teens with his Ballade for string orchestra in 1902.[3][18] His output included piano pieces, organ compositions, orchestral and chamber works, songs and part-songs, choral works, and an operetta.

Bredon Hill (1941) for violin and orchestra, influenced by the poem In summertime on Bredon by A. E. Housman,[1] was commissioned by the BBC to reinforce the notion of national music during the war years. Bredon Hill was the most-publicised new work commissioned by the BBC for the war effort, and in the autumn of 1941 it was broadcast to Africa, North America, and the Pacific.[19] The composition takes its name from Bredon Hill, a low rise in the Worcestershire countryside that Harrison could see from his home in Malvern.[1]

His biographer, Geoffrey Self, writes that after 1940 Harrison wrote a series of substantial works; he notes particularly Bredon Hill and the Sonata in C Minor for Viola and Piano (1945), works which, in Self's view, are influenced respectively by Brahms and Vaughan Williams.[13] Harrison's most ambitious works were his Mass in C (1936–47) and Requiem (1948–57), works which Self describes as "conservative and contrapuntally complex, influenced by Bach and Verdi respectively, [with] a mastery of texture and a massive yet balanced structure".[13]

Literature

editHarrison's writings about music include Handbook for Choralists (London, 1928) and Brahms and his Four Symphonies (1939), and chapters on Mendelssohn, Schumann, Brahms and Dvořák in The Symphony (London, 1967), a two-volume work edited by Robert Simpson and dedicated to Harrison's memory.[13]

Discography

edit- Julius Harrison Orchestral Music; Hubert Clifford Serenade for Strings; Dutton Epoch CDLX7174 (2006)

Matthew Trussler (violin); Andrew Knight (harp); BBC Concert Orchestra conducted by Barry Wordsworth

- Worcestershire Suite for orchestra (1918)

- Bredon Hill, Rhapsody for violin and orchestra (1941)

- Troubadour Suite for orchestra (1944)

- Romance, a Song of Adoration for orchestra (1930)

- Prelude-Music for harp and string orchestra (1912)

- Widdicombe Fair, Humoresque for string orchestra (1916)

- Hubert Clifford – Serenade for Strings (1943)

- Samuel Coleridge-Taylor: Violin Concerto, Legend, Romance; Julius Harrison: Bredon Hill; Lyrita 317 (2008)

Lorraine McAslan (violin); London Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Nicholas Braithwaite

- Includes Julius Harrison – Bredon Hill, Rhapsody for violin and orchestra (1941) and music of Samuel Coleridge-Taylor

- Viola Sonatas: Edgar Bainton and Julius Harrison (World Premiere Recordings); 3 Pieces by Frank Bridge; British Music Society BMSCD415R (2008)

Martin Outram (viola); Michael Jones (piano)

- Includes Julius Harrison – Viola Sonata in C minor (1945) and music of Frank Bridge and Edgar Bainton

- 'Far Forest', from Severn Country (three sketches for piano, 1928). A Hundred Years of British Piano Miniatures Archived 23 November 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Grand Piano CD GP789 (2018), Duncan Honeybourne

Notes

edit- ^ a b c d France, John (2007). "Julius Harrison & Bredon Hill". MusicWeb International. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Baker, Anne Pimlott (2004). "Harrison, Julius Allan Greenway (1885–1963)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/67642. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ a b c d e f g "Worcestershire's other composer". Worcester News. 14 April 2001.

- ^ a b Martin Lee-Browne; Paul Guinery; Mark Elder (2014). Delius and His Music. Boydell & Brewer. p. 253. ISBN 9781843839590.

- ^ Young, Percy M. (1994). "Reviews of Books: Julius Harrison and the Importunate Muse by Geoffrey Self". Music & Letters. 75 (2). Oxford University Press: 309. doi:10.1093/ml/75.2.309.

- ^ a b "The Norwich Festival". The Manchester Guardian. 31 October 1908. p. 10.

- ^ "University musicians revive lost Cleopatra cantata". University of Bristol. 10 March 2016.

- ^ "Norwich Musical Festival". The Times. 31 October 1908. p. 13.

- ^ "London Symphony Orchestra". The Times. 6 December 1910. p. 13.

- ^ Lucas, p. 125.

- ^ a b Lucas, p. 131.

- ^ Lucas, p. 140.

- ^ a b c d Self, Geoffrey. "Harrison, Julius". Grove Music Online. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 29 February 2012. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- ^ F. H. (April 1936). "Hastings Festival". The Musical Times. 77 (1118): 364. doi:10.2307/918168. JSTOR 918168. (subscription required)

- ^ "1. The Early Years", by Frank Greatwich. "2. The 1950s". In: Michael Trott, ed. (2001). Half-Century The Elgar Society, 1951–2001 (PDF). Elgar Editions. pp. 3, 9. ISBN 0-9537082-2-5. Retrieved 3 December 2016.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Gregory, Andrew (1 May 2012). "Julius Harrison - 1885–1963". Harpenden History Society. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- ^ Norris, Gerald. A Musical Gazetteer of Great Britain & Ireland (1981), p 142

- ^ Mackie, Colin. "Julius Harrison: A Catalogue of the Orchestral Music" (PDF). Gulabin.com. Retrieved 19 December 2016.

- ^ Hughes, Meirion; Stradling, Robert (2001). English Musical Renaissance, 1840–1940. Manchester University Press. p. 200. ISBN 978-0-7190-5830-1.

References

edit- Lucas, John (2008). Thomas Beecham – An Obsession with Music. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-402-1.

Further reading

edit- Rubbra, Edmund (1950). Julius Harrison's Mass. Oxford University Press.

- Self, Geoffrey (1993). Julius Harrison and the Importunate Muse. Scolar Press. ISBN 0-85967-929-2

External links

edit- Bredon Hill: Rhapsody for Violin and Orchestra (audio). London Philharmonic Orchestra, Nicholas Braithwaite conducting; Lorraine McAslan solo violin