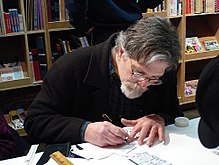

James William Woodring (born October 11, 1952) is an American cartoonist, fine artist, writer and toy designer. He is best known for the dream-based comics he published in his magazine Jim, and as the creator of the anthropomorphic cartoon character Frank, who has appeared in a number of short comics and graphic novels.

Jim Woodring | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | James William Woodring October 11, 1952 Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Occupation(s) | Cartoonist, fine artist, writer, toy designer |

| Notable work | Jim Frank Microsoft Comic Chat |

| Spouse | Mary Woodring |

| Website | jimwoodring |

Since he was a child, Woodring has experienced hallucinatory "apparitions", which have inspired much of his surreal work. He keeps an "autojournal" of his dreams, some of which have formed the basis of some of his comics. His most famous creation is fictional—the pantomime comics set in the universe he calls the Unifactor, usually featuring Frank. These stories incorporate a highly personal symbolism largely inspired by Woodring's belief in Vedanta from Hindu philosophy. He also does a large amount of surrealist painting, and has been the writer on a number of comics from licensed franchises published by Dark Horse and others.

Woodring identified Bimbo's Initiation as "one of the things that laid the foundation for my life's philosophy."[1]

Woodring has won or been nominated for a number of awards. He placed twice on The Comics Journal's list of the 100 best comics of the century, with the Frank stories ranked #55, and The Book of Jim ranked #71.

Biography

editThe elder of two children, Woodring was born in Los Angeles. He suffered from hallucinations (which he called "apparitions") of floating, gibbering faces over his bed (among other visions) when he was a child, and "was obsessed with death at a tender age"[2] and was afraid his parents would come into his bedroom and kill him. He had behavioral problems, finding himself unable to stop himself from doing things he knew he should not be doing, which he says he did not bring in line until he got married. Woodring has also been diagnosed with prosopagnosia.[3][4]

He graduated from high school in 1970 and went to Glendale Junior College for about two months. While there,

"I had the most significant hallucination of my life in this art history class. I took it as an omen that I should just get the hell out of school and stay out! [Laughs.] This hallucination was so much more interesting than the class — it seemed to have forced its way into the classroom and jumped out of the screen where these slides were being projected in order to tell me that I should be somewhere else. I felt that this image had gone to a lot of work to get into the building and get into that room and wait for the screen to turn blank and then appear at me to honk at me to go. So I did."

— Jim Woodring[2]

Woodring dropped out of college and spent the next year and a half as a garbage man.[2] During this time he developed a serious drinking problem, which lasted about eight years. He eventually quit drinking because he felt it was interfering with his growth as an artist.

Animation industry

editIn 1979[2] he was persuaded by his best friend[2][5] John Dorman to take work as an artist with the Ruby-Spears animation studio. He did "[s]toryboards during the production season and presentation work during the off-season." He did work for the cartoon shows Mister T, Rubik the Amazing Cube, and Turbo Teen, and he has often said that these were the worst cartoons ever produced. At that time, he formed friendships with and was somewhat mentored by celebrated comic book artists Gil Kane and Jack Kirby, who were both disgruntled with the comics business and were working in animation at the time.

Comics

editWhile working at Ruby-Spears he began self-publishing Jim, an anthology of comics, dream art and free-form writing which he described as an "autojournal". In 1986, Woodring was introduced by Gil Kane to Gary Groth of Fantagraphics Books. Jim was published as a regular series by Fantagraphics starting in 1986, to critical acclaim if less than spectacular sales, and Woodring became a full-time cartoonist. Frank, a wordless surrealist series which began as an occasional feature within Jim, became his best-known work, eventually spinning off into its own series in 1996. Most of the content of the first of the two volumes of Jim were collected as The Book of Jim in 1993, which was subsequently ranked as #71 on The Comics Journal's100 best comics of the century list.

"There are a lot of elements in the stories that mean something to me that shouldn't mean anything to anybody else, though of course I hope they do. I use these radially symmetrical shapes and bilateral symmetrical shapes and those have both got a different import to me. They stand for different specific qualities. So if Frank cracks open a jar and a bilat comes out, that means one thing. If he cracks it open and a jiva comes out, that means something else. It's like saying a stench came out or a mouse came out. I have this symbolic language worked out."

Woodring created a short-lived comics series for children, Tantalizing Stories, with Mark Martin. This was the place in which his character, Frank, first featured prominently, in stories that "have a dreamlike flow and an internal logic to them"[6] written in a "symbolic visual language"[6] that is "defined by thick, unforgiving cartoon lines that marry Walt Kelly with Salvador Dalí." [7] Most of the Frank stories have been done in black and white, but a number are notable for being in (usually painted) full color. In particular, Woodring was nominated for "Best Colorist" at the 1993 Eisner Awards for the story Frank in the River. The Comics Journal ranked the Frank stories #55 in its list of the 100 best comics of the century.

He has also worked as a freelance illustrator and comics writer, adapting the film Freaks with F. Solano Lopez for Fantagraphics and writing comics based on Aliens and Star Wars for Dark Horse.

Woodring produced a new Frank book in 2005 (The Lute String) and in 2010 his first graphic novel-length Frank book, Weathercraft, which found itself on a number of "Best of 2010" lists.[8][9][10] This was followed up with another, Congress of the Animals, in May 2011. Woodring says that, while he had been away from comics, he built up a backlog of new stories, and he intends to complete a total of four 100-page books like Weathercraft and Congress of the Animals, and then return to the types of stories he had done in Jim.[11]

Other projects

editIn June 2010, Scott Eder Gallery[12] in Brooklyn featured a solo show of Jim's Weathercraft art.[13]

A 48-minute DVD called Visions of Frank: Short Films by Japan's Most Audacious Animators was released by Japan's PressPop Music in 2005. It is a collection of nine animated shorts created between 2000 and 2005, each produced by a different artist or team interpreting a different Frank work. Aside from designing the packaging, Woodring had no input into the production of these films, leaving their interpretation entirely up to the animators.[14]

In 2010, a 93-minute documentary was released entitled The Lobster and the Liver: The Unique World of Jim Woodring,[15] directed by Jonathan Howells.

As of April 2011, Woodring keeps an infrequently updated blog,[16] where he sometimes posts panels from works-in-progress, including Weathercraft and Congress of the Animals, as well as other projects, such as new paintings and the construction and demonstration of a working seven-foot dip pen.

Woodring and his wife, Mary, have a son named Maxfield, who has published a graphic novel of his own titled OAK, printed with a grant from the Xeric Foundation, a page[17] from which was featured on November 18, 2012 as an entry for Woodring's blog.[16]

In October, 2022 woodring released his 400 page comics odyssey entitled One Beautiful Spring Day, featuring eccentric woodcut-style panels with clean black outlines and hatched shadows.[18]

Recurring characters

editFrank characters

editThe stories involving these characters occur in the surreal world Woodring calls the Unifactor.

- Frank

- A bipedal, bucktoothed animal of uncertain species with a short tail, described by Woodring as a "generic anthropomorph" and "naive but not innocent", "completely naive, capable of sinning by virtue of not knowing what he's really about."[19] The character design is reminiscent of old American animated shorts from the 1920s and 1930s, such as from Fleischer Studios. Usually he appears in black and white, but when he appears in colour his fur is purple.

Others

edit- Jim

- The artist himself featured prominently in most of his early dream comics.

- Pulque

- A perpetually drunken, man-sized, Spanish-speaking frog-creature. Pulque inexplicably hangs around with a group of suburban American children, despite the fact that he and the children cannot understand each other and are drawn in markedly different styles.

- Chip and Monk

- Boyhood friends.

- Big Red

- A large street cat who hunts and kills with an appropriately cat-like gusto. This is made chilling by Red's dialogue with his prey: "I'll kill you," shrieks a terrified possum, "I killed the old owl!" Red mutters an amused response, "That's nice," as he moves in for the kill.

Themes and motifs

edit- Dreams

- Woodring keeps a dream journal[2] and has turned several of these dreams into comics, which he "tr[ies] to make it as verbatim as possible."[2] Most of these were published in Jim. Since the mid-1990s he has turned away from stories explicitly based on real dreams, later saying: "I got sick of drawing myself. I don't ever want to draw myself again.".[6] He has since focused primarily on stories based in the Unifactor, the surreal Frank universe.

"It's tough to beat a frog for animal symbolism. When they're still, they're completely motionless, sometimes for hours. When they jump, they fly like greased lightning. They metamorphose, and ultimately live in two worlds. They are weirdly anthropomorphic, and of course they are beautiful to look at and fun to draw. I'll never tire of or be ambivalent toward frogs."

- Frogs

- feature prominently in Woodring's comics, and their symbolism seems to change from story to story. Often they are spiritually-minded but rather pompous creatures, but they can sometimes be sinister and alien. At other times, they are "average joes", struggling to protect their homes or their families from predators. A giant cartoon painting of a frog leaning against a wall made up the cover of the first issue of Jim in 1986, and frogs framed the cover of Weathercraft in 2010.

- Jivas

- appear frequently in Woodring's autobiographical dream comics and in Frank, where they appear as floating, flexible, colorful, occasionally radiant bulbous spindles resembling children's tops, and are both cognizant and motile, and neither vaporous nor altogether benevolent. Woodring has occasionally referred to them as "angels" and "conditioned souls".[14] In some Jim stories the Jivas can speak, and in one he accidentally pierces one's skin and it deflates like a balloon.

- The Unifactor

- The world in which Frank and associated characters appear, "a world where concepts like justice and logic read as alien",[20] "a picturesque but occasionally sinister world inhabited by alien plantlife and mischievous creatures, dream-logic and unknowable forces".[11]

The Unifactor functions under its own internal logic; death, destruction and mutilation in one story do not necessarily have any bearing on subsequent stories—Manhog removes the skin from his own leg in Manhog Beyond the Face,[21] which seems to leave no mark on him in other stories; and in a single issue of Jim, he has all his limbs, skin, and most of his facial features removed, becoming a mutilated jiva-like figure in one story, only to reappear later on in a separate story, apparently "normal", only to be killed, stuffed and sewn back up again.[22] On the positive side, however, Manhog, due to a chain of events started by a Jerry-Chicken, becomes civilized, cultured and the owner of a stately manor. This has no effect on his savage bestial nature in following stories.

Other work

editAs a comics historian, Woodring has written about T. S. Sullivant and other classic cartoonists for The Comics Journal. He also interviewed cartoonist Jack Davis for the publication.

Woodring illustrated Microsoft's Comic Chat program, an IRC client previously packaged with multiple versions of Internet Explorer.

He illustrated the cover of The Grifters' 1996 album Ain't My Lookout. He also illustrated the front cover, endpapers and the song "Toy Boy" in singer-songwriter Mika's 2009 EP Songs for Sorrow.[3][23]

For years, Woodring ran ads for "Jimland Novelties" in the back of his comics. These toys, books and oddities included a kit to make a frog's (severed) legs swim by hooking them up to a little motor, and another kit for leaving Woodring's own fingerprints around your home. For a time, Woodring was sending his readers free drawings, his "jiva portraits" of what he imagined their souls looked like. A sample of the "Jimland Novelties" pages can be glimpsed in the back of The Book of Jim.

Collaborations

editIn 1991 and 1992, Woodring illustrated the Harvey Pekar stories Snake, Watching the Media Watchers and Sheiboneth Beis Hamikdosh for American Splendor.[24] and for Introducing Dennis Eichhorn, which appeared in Real Stuff #1.

Woodring did the artwork for Dennis Eichhorn's The Meaning of Life in Real Stuff #3, and contributed the cover to issue #8.

Woodring wrote the scripts for the comic-book adaptation of Freaks, illustrated by Francisco Solano Lopez and colored by Mary Woodring.

In the 1990s, Woodring wrote a number of stories for Dark Horse Comics that were based on the Aliens franchise. The stories were illustrated by Kilian Plunkett, Jason Green and Francisco Solano Lopez, and have been collected as Aliens: Labyrinth in 1997 and Aliens: Kidnapped in 1999.

Released in November 2013, Woodring created an interpretative story based on artwork from Yo La Tengo's album Fade. The resultant product is a set of three soft vinyl figurines (sculpted by Tomohiro Yasui) representing the band members; they come with a DVD featuring an animated short (5:20 minutes) called The Tree, featuring music by Yo La Tengo (plus a "bonus comic" from Woodring is included with the rest).

Toys

editWoodring's strange toy creations have been sold in vending machines in Japan and are available in American comics shops. In a 2002 interview with The Comics Journal, Woodring said that he was gradually leaving comics behind because they simply were not lucrative enough, and he was increasingly concentrating on individual paintings. He made his return to comics at the turn of the decade, however, producing two new graphic novels.

Style

editStories

editThis section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2011) |

Woodring's work often has a nightmarish surreal quality. Woodring told The Comics Journal that under the right circumstances he is capable of "hallucinating like mad."[2] The desire to draw something that "wasn't there" was always of "paramount importance" to Woodring.

Artwork

editThis section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2011) |

Woodring's drawing style in the black-and-white Frank stories has often been mistaken for brushwork due to the greatly varying thickness of the linework typical of brush cartooning, but he has insisted,[note 1] and indeed demonstrated[citation needed], that it is done with a Brause #29 Index Finger dip pen.[25] He has said, "pen and ink for me is the ne plus ultra of drawing."[2]

In his Frank stories, Woodring employed a style that combined 1920s–30s Fleischer Studios-like character designs with an Eastern architectural and design flavor. He also makes heavy use of a distinctive controlled wavy line that adds contour and texture to the backgrounds, which has become his trademark.

Woodring also works in charcoal and paint (mostly in watercolor). A selection of these works (mostly charcoal) appeared in the collection Seeing Things in 2005.

Beliefs

editWoodring is a follower of Vedanta, and aspects of this philosophy often appear in his stories. He says, "Meditation is the uber-skill. It ought to be taught in elementary school."[14]

Artistic influences

editCartooning

editWoodring singles out for praise the cartoon work of Mark Martin, Justin Green, Rachel Bell, John Dorman, Mark Newgarden, Roy Thomkins, Peter Bagge, Terry LaBan, Chester Brown, Seth, Joe Matt, Robert Crumb, Charles Burns, Gilbert Hernandez, Jaime Hernandez, Lat,[19] Gil Kane and Jack Kirby (Woodring inked and colored Kirby's designs during his time at Ruby-Spears). He considers Kim Deitch to be "the most under-appreciated comic artist working today."[26]

Art

editHarry McNaught,[2][19] Boris Artzybasheff,[2] 17th Century Dutch painting,[2] Ingres,[2] Salvador Dalí

Literature

editWoodring has read widely in literature. Under the Volcano[6] by Malcolm Lowry and Les Misérables by Victor Hugo are two works that he has mentioned more than once in interviews.

Music

editWoodring frequently mentions Captain Beefheart, Bill Frisell as musical favorites, but also "schmaltzy, potent, cheap pop music with strings from the late 50s and early 60s, the Theme from A Summer Place, Holiday for Strings, the theme from Midnight Cowboy...that sort of dreck."[14] He also listens to a lot of classical music—his brother, with whom he's close, is a classical musician and has introduced him to much of what he listens to.[2][14]

Critical reception

editReaction amongst critics and fellow artists has generally been quite positive, despite low sales.[note 2]

"Frank, and I say this without a shred of hyperbole, is a work of true genius by one of the all-time greats."

Awards

editIn December 2006, he became one of the first group of United States Artists Fellows. His work was featured prominently at the Centre National de la Bande Dessinée et de l’Image in Angoulême, France as part of the international comics festival held there in January 2007. The following year, Woodring received an Inkpot Award at the 2008 San Diego Comic-Con, and he was awarded an Artist Trust/Washington State Arts Commission Fellowship in the fall of 2008. In November 2014 he received the Lynd Ward Prize from the Pennsylvania Center for the Book, for his graphic novel Fran.

| Year | Organisation | Award To | Award | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1993 | Harvey Awards[28] | Woodring | Best Colorist | Won |

| Tantalizing Stories Presents Frank in the River | Best Single Issue or Story | Won | ||

| Eisner Awards[29][30] | Frank in the River | Best Short Story | Nominated | |

| Best Colorist | Nominated | |||

| 1996 | Jim | Best Cover Artist | Nominated | |

| Best Writer/Artist, Humor | Nominated | |||

| 1998 | Ignatz Awards[31] | Frank Vol. 2 | Outstanding Graphic Novel or Collection | Nominated |

| 2003 | Ignatz Awards | The Frank Book | Outstanding Graphic Novel or Collection[32] | Nominated |

| Artist Trust | Woodring | Gap Award | Won | |

| 2006 | United States Artists | Woodring and Bill Frisell | Fellowship | Won |

| 2008 | Artist Trust | Woodring | Won | |

| Inkpot Awards | Woodring | Comic Arts | Won | |

| 2010 | Rasmuson Foundation and Artist Trust | Woodring | one month residency in Homer, Alaska | Won |

| The Stranger | Woodring | Genius of Literature | Won | |

| 2014 | Pennsylvania Center for the Book | Woodring | Lynd Ward Graphic Novel Prize | Won |

Collected works

editWoodring has published a large number of short works in diverse periodicals and anthologies. Below is a list of collections of some of those works, but a large amount has yet to be collected in book form. As of April 2011, many of these works are out of print.

Solo

edit| Year | Title | Publisher | ISBN | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1993 | The Book of Jim | Fantagraphics Books | 1-141-29836-8 | foreword by Mark Martin |

| 1994 | Frank Vol. 1 | 978-1-560-97153-5 | ||

| 1997 | Frank Vol. 2 | 978-1-56097-279-2 | ||

| 2002 | Trosper (with music by Bill Frisell) |

1-56097-426-5 | ||

| 2003 | The Frank Book | 1-56097-534-2 | foreword by Francis Ford Coppola | |

| Oneiric Diary | Dark Horse Comics | 1-59307-002-0 | notebook with blank pages | |

| 2004 | Pupshaw and Pushpaw | Press Pop | 4-9900812-9-3 | |

| 2005 | Seeing Things | Fantagraphics Books | 1-56097-648-9 | |

| The Lute String リュートの弦 |

Presspop Gallery | 978-4-90309-003-0 | ||

| 2006 | The Frank color stories | 978-4-90309-006-1 | ||

| 2008 | The Museum of Love and Mystery | 978-4-903090-14-6 | ||

| The Portable Frank | Fantagraphics Books | 978-1-56097-978-4 | foreword by Justin Green | |

| 2010 | Weathercraft | 978-1-60699-340-8 | ||

| 2011 | Congress of the Animals | 978-1-60699-437-5 | ||

| 2012 | Problematic: Sketchbook Drawings 2004–2012 | 978-1-60699-594-5 | ||

| 2013 | Fran | 978-1-60699-661-4 | ||

| 2018 | Poochytown | 978-1-68396-119-2 | ||

| 2020 | And Now Sir, Is This Your Missing Gonad? | 978-1-68396-326-4 | ||

| 2022 | One Beautiful Spring Day | Fantagraphics Books | 978-1-68396-555-8 | a compilation of Congress of the Animals, Fran and Poochytown, along with 100 pages never before published |

As writer

edit| Year | Title | Collaborator(s) | Publisher | ISBN |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1997 | Aliens: Labyrinth | Kilian Plunkett (Illustrator) |

Dark Horse Comics | 1-56971-245-X |

| 1998 | Star Wars: Jabba the Hutt: Art of the Deal | Art Wetherell Monty Sheldon (Illustrators) |

978-1569713105 | |

| 1999 | Aliens: Kidnapped | Jason Green, Francisco Solano Lopez (Illustrators) |

978-1569713723 |

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ "...I could never, ever, in a trillion years do what you do with a brush and paper. (Pen—J.W.)".

Letter from Ivan Brunetti in Jim Vol. II, #5, pg 18 (May 1995). Fantagraphics Books - ^ "But I read recently that only about 3000 copies of his comics are sold..."

Bob's Comic Reviews, February 1999

References

edit- ^ Groth, Gary. "Jim Woodring Interview". The Comics Journal #164 (December 1993), p. 83.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n 1993 interview Archived September 24, 2015, at the Wayback Machine with Gary Groth from The Comics Journal

- ^ a b "Jim Woodring". lambiek.net. October 11, 1952. Retrieved March 1, 2020.

- ^ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fdJ5LPa-Skc Jim Woodring speech Making Light VASD Program, around the 32:00 mark. 24 March 2016.

- ^ Woodring, Jim (January 29, 2011). "JOHN". Retrieved April 6, 2011. Blog post reminiscing about John Dorman upon his death

- ^ a b c d e interview with Gary Groth in the Comics Journal Special Edition Summer 2002 (excerpt Archived July 10, 2011, at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ Heater, Brian (September 16, 2008). "The Portable Frank by Jim Woodring". The Daily Crosshatch. Retrieved April 5, 2011.

- ^ "The 2011 Los Angeles Times Book Prizes ceremony honors the best books of 2010". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 10, 2017. Retrieved April 4, 2011.

- ^ "Best Books of 2010". Publishers Weekly. November 8, 2010. Retrieved April 4, 2011.

- ^ Wolk, Douglas (December 20, 2010). "The Best Graphic Novels of 2010". Time. Archived from the original on May 1, 2011. Retrieved April 4, 2011.

- ^ a b c Manning, Shaun (April 9, 2010). "Woodring Practices "Weathercraft" (interview)". Comic Book Resources. Retrieved April 15, 2011.

- ^ "scott eder gallery :: 18 bridge st. DUMBO :: comic book art". scottedergallery.com.

- ^ ScottEderGallery.com

- ^ a b c d e "The Words and Worlds of Jim Woodring". October 1, 2010. Archived from the original on October 4, 2010. Retrieved April 12, 2010.

- ^ "listing for The Lobster and the Liver". IMDb.

- ^ a b "The Woodring Monitor". jimwoodring.blogspot.com.

- ^ "Comic". 3.bp.blogspot.com. Retrieved March 1, 2020.

- ^ Thielman, Sam (August 9, 2022). "The Cute and Horrifying World of Jim Woodring". The New Yorker. ISSN 0028-792X. Retrieved July 25, 2023.

- ^ a b c Reilly, Chris (March 25–31, 1993). "Jim Woodring: From Tantalus to Revelations?". Retrieved April 12, 2011.

- ^ Stone, Tucker (June 1, 2010). "Description is a Myth". comixology.com. Archived from the original on June 5, 2010. Retrieved April 14, 2010.

- ^ Woodring, Jim. Jim Volume II, #1. Fantagraphics Books (December 1993 issue)

- ^ Woodring, Jim. Jim Volume II, #4. Fantagraphics Books (December 1994 issue, printed November 1994)

- ^ Jim Woodring speech Making Light VASD Program, around the 32:00 mark. 24 March 2016.

- ^ "Josh Neufeld Comix and Stories: And...: Harvey Pekar's Artists". Archived from the original on February 13, 2010. Retrieved February 5, 2010.

- ^ https://www.imdb.com/title/tt11230770/ [user-generated source]

- ^ "Toronto Comics Art Festival 2010: Jim Woodring". National Post. May 7, 2010. Retrieved April 5, 2011.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Daniel Clowes, from the back cover of The Portable Frank. Fantagraphics Books. 2008. ISBN 978-1-56097-978-4

- ^ "Harvey Awards". Fantagraphics Books/The Comics Journal. Archived from the original on March 24, 2012. Retrieved April 19, 2011.

- ^ "1993 Will Eisner Comic Industry Award Nominees and Winners". Retrieved April 19, 2011.

- ^ "1996 Will Eisner Comic Industry Award Nominees and Winners". Retrieved April 19, 2011.

- ^ Hahn, Joel. "1998 Ignatz Award Nominees and Winners". Retrieved May 2, 2011.

- ^ Hahn, Joel. "2003 Ignatz Award Nominees and Winners". Retrieved May 2, 2011.

Sources

edit- Lambiek: Jim Woodring

- Jim Woodring at the Grand Comics Database

- Jim Woodring at the Comic Book DB (archived from the original)

Further reading

edit- Bonar, Hugh (December 1993). "Screechy Peachy is Screaming". The Comics Journal (164). Fantagraphics Books: 44–46. ISSN 0194-7869.

External links

edit- Official website

- Demonstration of 7-foot pen (2011)

- Close reading of one panel of Woodring's work: Hatfield, Charles (January 8, 2011). "One-Panel Criticism: Holy Terror". thepanelists.org. Archived from the original on July 26, 2011. Retrieved April 12, 2011.

- Biography at Strangeco

- Brainyquote

Interviews

edit- Rudick, Nicole. "The Mind of a Worldly Man Is Like a Fly": A Jim Woodring Interview part 1 2 3 4. The Comics Journal. June 27, 2011. Retrieved 2011-06-28

- 2018 McCulloch, Joe (September 17, 2018). "Lit By an Invisible Source: Briefly, with Jim Woodring". The Comics Journal. Retrieved August 5, 2024.

- 2011 Video interview on YouTube. Seattle Channel. 2011-03-25. retrieved 2011-04-12

- 2010 Video Interview on The Dusty Wright Show (22 minutes)

- 2010 "The Words and Worlds of Jim Woodring". October 1, 2010. Archived from the original on October 4, 2010. Retrieved April 12, 2010.

- 2010 Heller, Jason (July 8, 2010). "Interview: Jim Woodring". The A.V. Club. Retrieved April 12, 2011.

- 2007 Heater, Brian (March 27, 2007). Interview: Jim Woodring Pt. 1 Pt. 2.[permanent dead link] Retrieved August 5, 2024.

- Groth, Gary (1993). "The Comics Journal #164 interview" (PDF). Fantagraphics. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 24, 2015. Retrieved April 12, 2011.

- Lambiek Comiclopedia article.