This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (February 2024) |

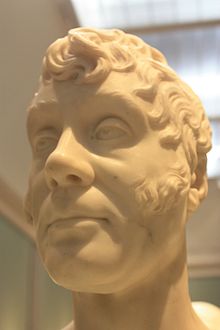

James Maitland, 8th Earl of Lauderdale, KT, PC (26 January 1759 – 10 September 1839) was Keeper of the Great Seal of Scotland and a Scottish representative peer in the House of Lords.[1]

The Earl of Lauderdale | |

|---|---|

| |

| Earl of Lauderdale | |

| Reign | 17 August 1789 – 10 September 1839 |

| Predecessor | James Maitland, 7th Earl of Lauderdale |

| Successor | James Maitland, 9th Earl of Lauderdale |

| Born | 26 January 1759 |

| Died | 10 September 1839 (aged 80) |

| Spouse(s) | Eleanor Todd |

| Issue | 10 |

| Father | James Maitland, 7th Earl of Lauderdale |

Early years

editBorn at Haltoun House near Ratho, the eldest son and heir of James Maitland, 7th Earl of Lauderdale, whom he succeeded in 1789, he became a controversial Scottish politician and writer. His tutor had been the learned Dr. Andrew Dalzell and James Maitland then attended the universities of Edinburgh and Glasgow, completing his education in Paris where, it is said, he became radicalised.

Parliamentary career

editUpon his return home in 1780, he was admitted a member of the Faculty of Advocates and successfully stood for election to parliament the same year. From 1780 until 1784 he was a member of parliament representing Newport and from 1784 to 1789, Malmesbury. In the House of Commons he supported the prominent Whig Charles Fox and took an active part in debate and was one of the managers of the Impeachment of Warren Hastings.

From 1789, in the House of Lords, where he was a Scottish representative peer, he was prominent as an opponent of the policy of William Pitt the Younger and the English government with regard to France.[1] He was a frequent speaker and also distinguished himself by his active opposition to the Habeas Corpus Suspension Act, the Sedition Bill, and other measures. Upon the outbreak of the French Revolution, of which he was thought to be in sympathy, he ostentatiously appeared in the house in the rough costume of Jacobinism.

In July 1792, he fought a bloodless duel with Benedict Arnold after impugning Arnold's honour in the House of Lords.[2]

French Revolution

editIn 1792, in the company of John Moore, Lord Lauderdale travelled again to France. The attack on the Tuileries and the imprisonment of King Louis XVI took place three days after the earl's arrival in the French capital. After the massacres of 2 September, the British ambassador having left Paris, the earl left Paris on the 4th for Calais. However, he returned to Paris the following month and did not leave for London until 5 December. Upon his return from France, he published a Journal during the residence in France from the beginning of August to the middle of December 1792.

According to the antiquarian Andrew Thomson, "James Maitland 8th Earl of Lauderdale was known as 'Citizen Maitland'. An extremist, he was in Paris during the French Revolution and was a personal friend of Jean-Paul Marat. He rarely visited Scotland". The earl had helped to found the British Society of the Friends of the People in 1792.

New peerage

editUpon the formation of the Grenville administration in February 1806, Lauderdale was made a peer of the United Kingdom as Baron Lauderdale of Thirlestane and sworn a member of the Privy Council. For a short time from July 1806 he was keeper of the Great Seal of Scotland.[1]

Napoleonic treaty

editOn 2 August 1806 the earl, fully fluent in French, departed for France, invested with full powers to conclude peace, the negotiations for which had been for several weeks carried on by the Earl of Yarmouth. Arriving on the 5th he and Yarmouth set about the arduous task of treating with Napoleon and Tallyrand. Yarmouth was recalled on the 14th and Lauderdale was left alone.

In his 'Memoirs ' Eugène François Vidocq wrote that circa Battle of Copenhagen (1807) Boulogne was also bombed. According to Vidocq at this moment Lauderdale was right in Boulogne, and was almost lynched by Frenchmen.

He was an Englishman, and the exasperated people were desirous of revenging themselves on him: they surrounded him, mobbed him, and pressed upon him; and in defiance of the protection of two officers who were attending him, they showered stones and mud upon him from all sides. Pale, trembling, and faltering, the peer thought he was about to fall a sacrifice, when sword in hand, I cleared my way through the rabble, crying 'Destruction to whoever strikes him!' I harangued the multitude, dispersed them, and led the way to the harbour, where, without being subjected to further insult, he embarked on board a flag of truce boat. He soon reached the English squadron, which the next evening renewed the bombardment.

Following the renewal of hostilities he left Paris for London on 9 October. A full account of the progress and termination of the negotiations appeared in the London Gazette of 21 October 1806.

After acting as the leader of the Whigs in Scotland, Lauderdale became a Tory and voted against the Reform Bill of 1832.[1] Lord Lauderdale was made a Privy Counsellor in 1806 and a Knight of the Thistle in 1821.

Banner dispute

editIn 1672 on the death of the Earl of Dundee, the Duke of Lauderdale was appointed Hereditary Bearer for the Sovereign of the Standard of Scotland, and this right was retained by his heirs until 1910.

In 1790, James Maitland, 8th Earl of Lauderdale matriculated arms in the character of Hereditary Bearer for the Sovereign of the Standard of Scotland and Hereditary Bearer for the Sovereign of the National Flag of Scotland.

In 1952 after a meeting with the Earls of Lauderdale and Dundee the Lord Lyon advised the Queen to confirm the Earl of Lauderdale's right to bear the saltire as the Bearer of the National Flag of Scotland, and to confirm that the Earl of Dundee as the Bearer of the Royal Banner bears the Royal Standard of the lion rampant.

Writings

editMaitland wrote an Inquiry into the Nature and Origin of Public Wealth (1804 and 1819), in which he introduced the concept that has come to be known as the "Lauderdale Paradox": there is an inverse correlation between public wealth and private wealth; an increase in the one can only come at the cost of a decrease in the other.[3] This work, which was translated into French and Italian, produced a controversy between the author and Lord Brougham; The Depreciation of the Paper-currency of Great Britain Proved (1812); and other writings of a similar nature.[1] The "Inquiry" was the first work to draw attention to the economic consequences of a budget surplus or deficit and its influence on the expansion or contraction of the economy, and was thus the basis of the later Keynesian economic theories which are now widely applied.

Death

editHe died at Thirlestane Castle, near Lauder, Berwickshire, at 80.

He is buried in the Maitland vault, also called the Lauderdale Aisle, at St Mary's Collegiate Church, Haddington.

Family

editOn 15 August 1782, he married Eleanor Todd (1762–1856), the only daughter and heiress of Anthony Todd, Secretary of the General Post Office. They had ten children:

- Lady Eleanor, married James Balfour (parents of James Maitland Balfour MP, and grandparents of Prime Minister Arthur Balfour)

- Lady Mary, married Edward Stanley of Cross Hall, near Ormskirk. Mother of Edward Stanley MP.

- Lady Julia, married in 1823 Sir John Warrender, 5th Baronet (1786–1867)

- James Maitland, 9th Earl of Lauderdale (1784–1860)

- Admiral Anthony Maitland, 10th Earl of Lauderdale (1785–1863)

- Five other sons.

None of his seven sons were married.

Works

edit- An Inquiry into The Nature and Origin of Public Wealth and into the Means and Causes of its Increase Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine 1804 (second edition 1819)

References

edit- ^ a b c d e One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Yorke, Philip Chesney (1911). "Lauderdale, John Maitland, Duke of s.v. James Maitland, 8th earl of Lauderdale". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 16 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 280.

- ^ Fahey, Curtis (1983). "Arnold, Benedict". In Halpenny, Francess G (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. V (1801–1820) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press. Retrieved 9 December 2007.

- ^ Clark, Brett; Foster, John Bellamy (2010). "Marx's Ecology in the 21st Century" (PDF). World Review of Political Economy. 1 (1): 142.

- Anderson, William, The Scottish Nation, Edinburgh, 1867, vol.i, p. 637–638.

- Lauder & Lauderdale, by Andrew Thomson, FSA (Scot), Galashiels, 1902.

- Barker, George Fisher Russell (1893). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 35. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 355–357.

- Leigh Rayment's Peerage Pages [self-published source] [better source needed]