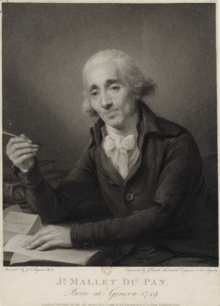

Jacques Mallet du Pan (5 November 1749 – 10 May 1800) was a Genevan political journalist and propagandist.[1] A Calvinist thinker and Counter-Revolutionary reformer, he opposed extreme positions held by both Revolutionary and Counter-Revolutionary partisans during the French Revolution.[2]

Jacques Mallet du Pan | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 5 November 1749 Céligny, Republic of Geneva |

| Died | 10 May 1800 (aged 50) Richmond, London, United Kingdom |

| Signature | |

Life

editPre-French Revolution

editMallet du Pan was born in Céligny to a Protestant minister from an old Huguenot family.[citation needed] He was educated at Geneva, and through the influence of Voltaire was appointed as a Professor of French Literature at Kassel, however he soon resigned from this position. In 1771, at a time of mounting opposition to the oligarchic rule of the upper class, he wrote what was considered by the ruling council in Geneva to be an inflammatory pamphlet entitled Compte rendu de la défense des citoyens bourgeois. It was condemned by the council and burnt in the main square.

Hoping to find more independence as writer, he travelled to London to find Simon Nicholas Henri Linguet and propose that he become co-editor in the production of the "Annales Politiques", to which Linguet agreed. This collaboration was broken in September 1779 with Linguet's imprisonment in the Bastille. Du Pan then brought the Annales to Geneva to continue the work himself (1781–1783) under the title Mémoires historiques, politiques et littéraires.[citation needed] After Linguet's release from the Bastille in 1782, Du Pan felt he had to distance himself from the Annales for fear of being accused of profiting from Linguet's misfortune by seizing his property during his imprisonment, and he discontinued this work.[citation needed]

Following the Geneva Revolution of 1782 and several years in exile he adopted the ideological position of the juste milieu (the middle way). This position stood in opposition to both revolutionary and counter-revolutionary forces and brought him to a second exile. He went to establish himself in Paris, where he had a reputation as a skilled publicist.[citation needed] While in Paris he worked and lived with the book-seller Charles-Joseph Panckoucke, publishing a new journal titled Journal historique et politique de Genève from January 1781

From 1783 he incorporated this work with Panckoucke into an editorial position at the Mercure de France, where Panckoucke was the publisher.[3] In all the political writings published by Mallet du Pan before the revolution he used his position to propagandise in favour of a constitutional monarchy in France. He supported the introduction of a system similar to the constitutional monarchy of Britain, which he believed was possible to apply in France with some light modifications.[citation needed] Staunchly loyal to his ideological positions, he used his post in the Mercure to defend them ferociously and polemicise against those he saw as not sharing his positions. In his writings, he came to increasingly criticise the French Revolution.[2]

French Revolution

editAt the outbreak of the French Revolution, he sided with MPs who wanted to implement a constitutional monarchy and in 1789 he joined the Royalist camp. He viewed the period from 1789, including the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen as a matrice de la démagogie, or a populist circus. He continued political writings and was known for an improper but fiery and frank style that served to evoke the passions of his readers and was able to predict fairly accurately the trajectory of the Revolutionary movement. This combination of factors led to the quick development of a reputation amongst the revolutionary partisans, who denounced him as an enemy to liberty.[citation needed] Mallet, impassioned by the perceived excess of the Revolutionaries, threw himself into the work of the Royalist party, attacking the violence of the Revolution and the people who supported revolutionary principles.

Seen as a safe ally and held in high-esteem by Louis XVI for his counter revolutionary work he was sent on a mission to Frankfurt from 1791–1792 to secure the sympathy and intervention of the German princes. From Germany, he traveled to Switzerland and from Switzerland to Brussels in the Royalist interest.[4] In 1792, he was charged by King Louis XVI to draw up a manifesto in the name of emigrants and coalition powers. The manifesto, believed to have been written by Jérôme-Joseph Geoffroy de Limon and published by Panckoucke, Mallet's old collaborator, was known as the Brunswick Manifesto[5] and declared that if the French royal family was harmed, French civilians would be harmed by the coalition powers. He published a number of anti-revolutionary pamphlets, and a violent attack on Bonaparte and the Directory resulted in his being exiled in 1797 to Berne.[4]

Exile

editMallet fled France on 10 August 1792, initially to Geneva until the advance of the French army forced him to move on. Briefly staying in Brussels before again fleeing the French army he came to Bern, where he would write Considérations sur la nature de la Révolution de France et sur les causes qui en prolongent la durée in 1793. A man of order and property, as hostile to the bourgeoise men of money as he was to Girondins, in this work he analysed the revolution as a revolt of the poor. He denounced the weakness of the Church, the Nobility, and the men of property in the third estate before finally denouncing the non-propertied and the "barbarians". He believed the French had given into the force of things, but in doing so had debased the culture of the whole of Europe. It is in this widely circulated essay that he coined the adage "like Saturn, the Revolution devours its children",[6] which originally appeared as "A l'exemple de Saturne, la révolution dévore ses enfants".[7][8] Translated into English at the time, the essay was read by and influenced William Pitt's views.[7]

In 1798, he came to London, where he founded the Mercure britannique.[4] He died of consumption at Richmond, Surrey, on 10 May 1800, leaving his widow, Françoise Valier, and three children, who received a pension from the British government.

Posterity

editHis son Jean Louis Mallet (John Lewis Mallet) (1775–1861) had a career in the British civil service, becoming secretary of the Board of Audit (the Audit Office). Mallet's grandson, Sir Louis Mallet (1823–1890), also entered the civil service in the Board of Trade and rose to be an economist and a member of the Council of India.[4] His great-grandson was Victor Mallet, a diplomat and author.

Works

edit- Du péril de la balance politique de l'Éurope, 1789

- Réflexions de M. Mallet-du-Pan, calviniste génevois, sur la conduite actuelle du clergé de France, & sur le nouveau serment dont on lui impose l'obligation, 1791

- Du principe des factions en général et de celles qui divisent la France, 1791

- Examen critique du rapport et du projet de loi sur la résidence des fonctionnaires publics, proposés le 23 février, à l'Assemblée nationale, 1791

- Considérations sur la nature de la révolution de France et sur les causes qui en prologent la durée, 1793. Paris, réédition par les Éditions du Trident, 2008

- Correspondance politique, pour servir à l'histoire du républicanisme français, 1796

- Essay historique sur la destruction de la ligue et de la liberté Helvétique, 1798

- Mercure Britannique; ou notices historiques et critiques sur les affaires du tems. Volume I; Volume II; Volume III; Volume IV; Volume V, 1798-1800

- Correspondence inédite avec la cour de Vienne (1794-8) Tome premier; Tome second, 1884

- Mémoires et correspondance de Mallet du Pan : pour servir à l'histoire de la révolution française recueillis et mis en ordre par A. Sayous, Paris 1851, 2 volumes.

Further reading

edit- Mallet du Pan's Mémoires et correspondance, edited by A. Sayous (Paris, 1851).

- Mallet du Pan and the French Revolution (1902) by Bernard Mallet, son of Sir Louis Mallet, author also of a biography of his father (1900)

- Acomb, Frances Dorothy. Mallet du Pan, 1749-1800: A Career in Political Journalism, Duke University Press (1973)[9]

References

edit- ^ Jacques Mallet du Pan, in the Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- ^ a b Sous la direction de Jean-Clément Martin, Dictionnaire de la Contre-Révolution, Jean-Clément Martin, « Mallet du Pan, Jacques », éd. Perrin, 2011, p. 359.

- ^ Kulstein, David I. (1966). "The Ideas of Charles-Joseph Panckoucke, Publisher of the Moniteur Universel, on the French Revolution". French Historical Studies. 4 (3): 304–319. doi:10.2307/285905. ISSN 0016-1071.

- ^ a b c d One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Mallet du Pan, Jacques". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 17 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 491–492.

- ^ Michel Winock, L’échec au Roi, 1791-1792, Paris, Olivier Orban, 1991, ISBN 2-85565-552-8, p. 262.

- ^ Deborah Kennedy (2002). Helen Maria Williams and the Age of Revolution. Bucknell University Press. p. 113. ISBN 978-0-8387-5511-2.

- ^ a b Sir Bernard Mallet (1902). Mallet du Pan and the French revolution. Longmans, Green. p. 164.

- ^ Jacques Mallet du Pan (1793). Considerations sur la nature de la revolution de France. p. 80.

- ^ Mackrell, J.Q.C. (1976). "Reviews : Frances Acomb, Mallet Du Pan (1749-1800). A career in political journalism, Durham, North Carolina, Duke University Press, 1973. xii + 304 pp. $11.75". European Studies Review. 6 (1): 149–150. doi:10.1177/026569147600600111. ISSN 0014-3111.