Isaac Lee Hayes Jr. (August 20, 1942 – August 10, 2008) was an American singer, songwriter, composer, and actor. He was one of the creative forces behind the Southern soul music label Stax Records in the 1960s,[4] serving as an in-house songwriter with his partner David Porter, as well as a session musician and record producer. Hayes and Porter were inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame in 2005 in recognition of writing scores of songs for themselves, the duo Sam & Dave, Carla Thomas, and others. In 2002, Hayes was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.[5]

Isaac Hayes | |

|---|---|

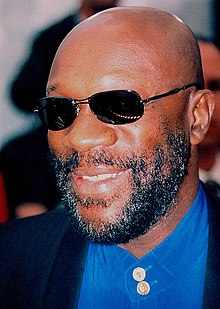

Hayes in 1998 | |

| Born | Isaac Lee Hayes Jr. August 20, 1942 Covington, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Died | August 10, 2008 (aged 65) Memphis, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Burial place | Memorial Park Cemetery, Memphis, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1950–2008 |

| Spouses | Dancy Hayes

(m. 1960, divorced)Emily Ruth Watson

(m. 1965; div. 1972)Mignon Harley

(m. 1973; div. 1986)Adjowa Hayes (m. 2005) |

| Children | 11, including Isaac III |

| Musical career | |

| Genres | |

| Instruments |

|

| Labels | |

"Soul Man," written by Hayes and Porter and first performed by Sam & Dave, was recognized as one of the most influential songs of the past 50 years by the Grammy Hall of Fame. It was also honored by the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, Rolling Stone magazine, and the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) as one of the Songs of the Century. During the late 1960s, Hayes also began a career as a recording artist. He released several successful soul albums such as Hot Buttered Soul (1969) and Black Moses (1971). In addition to his work in popular music, Hayes worked as a film composer.

Hayes was known for his musical score for the film Shaft (1971). For the "Theme from Shaft," he was awarded the Academy Award for Best Original Song in 1972, making him the third black person, after Hattie McDaniel and Sidney Poitier, to win an Academy Award in any competitive field covered by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Hayes also won two Grammy Awards that same year. Later, he won his third Grammy for his album Black Moses.

In 1992, Hayes was crowned honorary king of the Ada region of Ghana in recognition of his humanitarian work there.[6] He acted in films and television, such as in the movies Truck Turner (1974), Escape from New York (1981) and I'm Gonna Git You Sucka (1988), and as Gandolf "Gandy" Fitch in the TV series The Rockford Files (1974–1980). Hayes also voiced the character Chef in the Comedy Central animated series South Park from its debut in 1997 until his controversial departure in 2006.

On August 5, 2003, Hayes was honored as a BMI Icon at the 2003 BMI Urban Awards for his enduring influence on generations of musicians.[7] Throughout his songwriting career, Hayes received five BMI R&B Awards, two BMI Pop Awards, two BMI Urban Awards and six Million-Air citations. As of 2008, his songs had generated more than 12 million performances.[8][clarification needed]

Early life

editIsaac Lee Hayes Jr. was born in Covington, Tennessee,[9] the second child of Eula (née Wade) and Isaac Hayes Sr.[10] After his mother died young and his father abandoned his family, Hayes was raised by his maternal grandparents,[11] Mr. and Mrs. Willie Wade Sr. The child of a sharecropper family, Hayes grew up working on farms in the Tennessee counties of Shelby and Tipton. At age five, Hayes began singing at his local church and he taught himself to play the piano, Hammond organ, flute, and saxophone.[citation needed]

Hayes dropped out of high school, but his former teachers at Manassas High School in Memphis encouraged him to complete his diploma, which he did at the age of 21. After graduating from high school, Hayes was offered several music scholarships from colleges and universities. He turned down all of them to provide for his immediate family, working at a meat-packing plant in Memphis by day and playing nightclubs and juke joints several evenings a week in Memphis and nearby northern Mississippi.[11] Hayes's first professional gigs, in the late 1950s, were as a singer at Curry's Club in North Memphis, backed by Ben Branch's houseband.[12]

Career

edit1963–1974: Stax Records and Shaft

editHayes began his recording career in the early 1960s, as a session musician for acts recorded by the Memphis-based Stax Records.[13] He later wrote a string of hit songs with songwriting partner David Porter, including "You Don't Know Like I Know," "Soul Man,"[14] "When Something Is Wrong with My Baby" and "Hold On, I'm Comin'" for Sam & Dave. Hayes, Porter and Stax studio band Booker T. & the M.G.'s were also the producers for Sam & Dave, Carla Thomas and other Stax artists during the mid-1960s. One of the first Stax records Hayes played on was "Winter Snow" by Booker T. and The M.G.s (Stax 45–236), which indicates "Introducing Isaac Hayes on piano" on the label.

Hayes-Porter contributed to the Stax sound of this period, and Sam & Dave credited Hayes for helping develop both their sound and style. In 1968, Hayes released his debut album, Presenting Isaac Hayes, a jazzy, largely improvised effort that was commercially unsuccessful.[15]

Stax then went through a major upheaval, losing its biggest star when Otis Redding died in a plane crash in December 1967, and then losing its back catalog to Atlantic Records in May 1968. As a result, Stax executive vice president Al Bell called for 27 new albums to be completed in mid-1969; Hayes's second album, Hot Buttered Soul was the most successful of these releases.[15]

On Hot Buttered Soul, Hayes reinterpreted "Walk On By" (previously recorded by Dionne Warwick) into a 12-minute exploration. "By the Time I Get to Phoenix" starts with an eight-minute-long monologue[16] before breaking into song, and the lone original number, the funky "Hyperbolicsyllabicsesquedalymistic" runs nearly ten minutes, a significant break from the standard three-minute soul/pop songs. "Walk On By" would be the first of many times Hayes would take a Burt Bacharach standard, generally known as three-minute pop songs by Dionne Warwick or Dusty Springfield, and transform it into a soulful, lengthy and almost gospel number.[citation needed]

In 1970, Hayes released two albums, The Isaac Hayes Movement and ...To Be Continued. The former stuck to the four-song template of his previous album. Jerry Butler's "I Stand Accused" begins with a trademark spoken word monologue, and Bacharach's "I Just Don't Know What to Do with Myself" is re-worked.[citation needed] The latter album included "The Look of Love," another Bacharach song transformed into an 11-minute epic of lush orchestral rhythm (mid-way it breaks into a rhythm guitar jam for a couple of minutes before suddenly resuming the slow love song). An edited three-minute version was issued as a single.[17] The album featured the instrumental "Ike's Mood," which segues into a version of "You've Lost That Loving Feeling." Hayes released a Christmas single, "The Mistletoe and Me" (with "Winter Snow" as a B-side).[citation needed]

In early 1971, Hayes composed music for the soundtrack of the blaxploitation film Shaft (he appeared in a cameo role as a bartender). The title theme, with its wah-wah guitar and multi-layered symphonic arrangement, would become a worldwide hit single, and spent two weeks at number one in the Billboard Hot 100 in November. The remainder of the album was mostly instrumentals covering big beat jazz, bluesy funk, and hard Stax-styled soul. The other two vocal songs, the social commentary "Soulsville" and the 19-minute jam "Do Your Thing," would be edited down to hit singles.[17] He won an "Academy Award for Best Original Song" for the "Theme from Shaft," and in addition was nominated for Best Original Dramatic Score. Later in the year, Hayes released a double album, Black Moses, that expanded on his earlier sounds and featured The Jackson 5's song "Never Can Say Goodbye." Another single, "I Can't Help It," was not featured on the album.[citation needed]

In 1972, Hayes would record the theme tune for the television series The Men and release a hit single (with "Type Thang" as a B-side).[17] He released a couple of other non-album singles during the year, such as "If Loving You Is Wrong (I Don't Want to Be Right)" and "Rolling Down a Mountainside." Atlantic would re-release Hayes's debut album this year with the new title In The Beginning.[18]

Hayes was back in 1973 with an acclaimed live double album, Live at the Sahara Tahoe, and followed it up with the album Joy. He moved away from cover songs with this album. An edited version of the title track would be a hit single.[19]

In 1974, Hayes was featured in the blaxploitation films Three Tough Guys and Truck Turner, and he recorded soundtracks for both. Tough Guys was almost devoid of vocals and Truck Turner yielded a single with the title theme. The soundtrack score of Truck Turner was eventually used by filmmaker Quentin Tarantino in the Kill Bill film series, and has been used for over 30 years as the opening score of Brazilian radio show Jornal de Esportes on the Jovem Pan station.[citation needed]

Unlike most African American musicians of the period, Hayes did not sport an Afro haircut; his bald head became one of his defining characteristics.[citation needed]

1974–1977: HBS, basketball team ownership, and bankruptcy

editBy 1974, Stax Records was having serious financial problems, stemming from problems with overextension and limited record sales and distribution.[citation needed] Hayes himself was deep in debt to Union Planters Bank, which administered loans for the Stax label and many of its other key employees. In September of that year, Hayes sued Stax for $5.3 million. As Stax was in deep debt and could not pay, the label made an arrangement with Hayes and Union Planters: Stax released Hayes from his recording and production contracts, and Union Planters would collect all of Hayes's income and apply it towards his debts.[citation needed]

Hayes formed his own label, Hot Buttered Soul, which released its product through ABC Records.[20] His new album, 1975's Chocolate Chip, saw Hayes embrace the disco sound with the title track and lead single. "I Can't Turn Around" would prove a popular song as time went on. This would be Hayes's last album to chart in the top 40 for many years. Later in the year, the all-instrumental Disco Connection album fully embraced disco.[citation needed]

On July 17, 1974, Hayes, along with Mike Storen, Avron Fogelman, and Kemmons Wilson, took over ownership of the American Basketball Association team the Memphis Tams.[21] The prior owner was Charles O. Finley, the owner of the Oakland A's baseball team. Hayes's group renamed the team the Memphis Sounds. Despite a 66% increase in home attendance, hiring well regarded coach Joe Mullaney and, unlike in the prior three seasons, making the 1975 ABA Playoffs (losing to the eventual champion Kentucky Colonels in the Eastern Division semi-finals), the team's financial problems continued. The group was given a deadline of June 1, 1975, to sell 4,000 season tickets, obtain new investors and arrange a more favorable lease for the team at the Mid-South Coliseum. However, the group did not come through and the ABA took over the team, selling it to a group in Maryland that renamed the team the Baltimore Hustlers and then the Baltimore Claws before the club finally folded during preseason play for the 1975–1976 season.[22]

In 1976, the album cover of Juicy Fruit featured Hayes in a pool with naked women, and spawned the title track single and the classic "Storm Is Over." Later the same year the Groove-A-Thon album featured the singles "Rock Me Easy Baby" and the title track. However, while all these albums were regarded as solid efforts, Hayes was no longer selling large numbers. He and his wife were forced into bankruptcy in 1976, as they owed over $6 million. By the end of the bankruptcy proceedings in 1977, Hayes had lost his home, much of his personal property, and the rights to all future royalties earned from the music he had written, performed, and produced.[23]

1977–1995: Polydor, hiatus, and film work

editIn 1977, Hayes was back with a new deal with Polydor Records, a live album of duets with Dionne Warwick did moderately well, and his comeback studio album New Horizon sold better and enjoyed a hit single "Out The Ghetto," and also featured the popular "It's Heaven To Me." 1978's For the Sake of Love saw Hayes record a sequel to "Theme from Shaft" ("Shaft II"), but was best known for the single "Zeke The Freak," a song that would have a shelf life of decades and be a major part of the House movement in the UK. The same year, Fantasy Records, which had bought out Stax Records, released an album of Hayes's non-album singles and archived recordings as a "new" album, Hotbed, in 1978. In 1979, Hayes returned to the Top 40 with Don't Let Go and its disco-styled title track that became a hit single (U.S. #18), and also featured the classic "A Few More Kisses To Go." Later in the year he added vocals and worked on Millie Jackson's album Royal Rappin's, and a song he co-wrote, "Deja Vu," became a hit for Dionne Warwick and won her a Grammy for best female R&B vocal. Neither 1980s And Once Again or 1981's Lifetime Thing produced notable songs or big sales, and Hayes chose to take a break from music to pursue acting.[citation needed]

In the 1970s, Hayes was featured in the films Shaft (1971) and Truck Turner (1974); he also had a recurring role in the TV series The Rockford Files as an old cellmate of Rockford's, Gandolph Fitch (who always referred to Rockford as "Rockfish" much to his annoyance), including one episode alongside duet-partner Dionne Warwick. In the 1980s and 1990s, he appeared in numerous films, notably Escape from New York (1981), I'm Gonna Git You Sucka (1988), Prime Target (1991), and Robin Hood: Men in Tights (1993), as well as in episodes of The A-Team and Miami Vice. He also attempted a musical comeback, embracing the style of drum machines and synth for 1986s U-Turn and 1988s Love Attack, though neither proved successful. In 1991, he was featured in a duet with fellow soul singer Barry White on White's ballad "Dark and Lovely (You Over There)."[citation needed]

1995–2006: Return to prominence and South Park

editIn 1995, Hayes appeared as a Las Vegas minister impersonating himself in the comedy series The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air. He launched a comeback on the Virgin label in May 1995 with Branded, an album of new material that earned impressive sales figures as well as positive reviews from critics who proclaimed it a return to form.[24] A companion album released around the same time, Raw & Refined, featured a collection of previously unreleased instrumentals, both old and new. For the 1996 film Beavis and Butt-Head Do America, he wrote a version of the Beavis and Butt-Head theme in the style of the Shaft theme.[citation needed]

Hayes joined the founding cast of Comedy Central's animated TV series South Park. He provided the voice for the character of "Chef", the amorous elementary-school lunchroom cook, from the show's debut on August 13, 1997 (one week shy of his 55th birthday), through the end of its ninth season in 2006. The role of Chef combined his work both as an actor and as a singer, thanks to the character's penchant for making conversational points in the form of crudely suggestive soul songs. A song from the series performed by Chef, "Chocolate Salty Balls (P.S. I Love You)," received international radio airplay in 1999. It reached number one on the UK singles chart and also on the Irish singles chart. The track also appeared on the album Chef Aid: The South Park Album in 1998.[25][26][27]

In 2000, Hayes appeared on the soundtrack of the French movie The Magnet on the song "Is It Really Home" written and composed by rapper Akhenaton (IAM) and composer Bruno Coulais. In 2002, Hayes was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. After he played a set at the 2002 Glastonbury Festival, a documentary highlighting Isaac's career and his impact on many of the Memphis artists in the 1960s onwards was produced, Only The Strong Survive.[citation needed] In 2004, Hayes appeared in a recurring minor role as the Jaffa Tolok on the television series Stargate SG-1. The following year, he appeared in the critically acclaimed independent film Hustle & Flow. He also had a brief recurring role in UPN/The CW's Girlfriends as Eugene Childs (father of Toni).[citation needed]

South Park Scientology episode

editIn the South Park episode "Trapped in the Closet," a satire of Scientology that aired on November 16, 2005, Hayes did not appear in his role as Chef. In an interview for The A.V. Club on January 4, 2006, Hayes was asked about the episode. He said that he told the creators, Matt Stone and Trey Parker, "Guys, you have it all wrong. We're not like that. I know that's your thing, but get your information correct, because somebody might believe that shit, you know?" He then told them to take a couple of Scientology courses to understand what they do. In the interview, Hayes defended South Park's style of controversial humor, noting that he was not pleased with the show's treatment of Scientology, but saying that he "understands what Matt and Trey are doing."[28]

Departure from South Park

editOn March 13, 2006, a statement was issued in Hayes's name, indicating that he was asking to be released from his contract with Comedy Central, calling recent episodes that satirized religious beliefs intolerant. "There is a place in this world for satire, but there is a time when satire ends and intolerance and bigotry towards religious beliefs of others begins", he was quoted as saying in the press-statement. However, the statement did not directly mention Scientology. A response from Stone said that Hayes's complaints stemmed from the show's criticism of Scientology and that he "has no problem –and he's cashed plenty of checks– with our show making fun of Christians, Muslims, Mormons, or Jews."[29][30]

On March 20, 2006, two days before the episode "The Return of Chef" aired, Roger Friedman of Fox News reported having been told that the March 13 statement was made in Hayes's name, but not by Hayes himself. He wrote: "Isaac Hayes did not quit South Park. My sources say that someone quit it for him. ... Friends in Memphis tell me that Hayes did not issue any statements on his own about South Park. They are mystified."[31] In a 2016 oral history of South Park in The Hollywood Reporter, Hayes's son Isaac Hayes III said the decision to leave the show was made by his father's entourage, all of whom were ardent Scientologists, and that it was made after Hayes suffered a stroke, leaving him vulnerable to outside influence and unable to make such decisions on his own.[32]

The first South Park episode that premiered after Hayes's death, "The China Probrem," was dedicated to him.[33]

2006–2008: Final years

editHayes's income was sharply reduced as a result of leaving South Park.[34] There followed announcements that he would be touring and performing. A Fox News reporter present at a January 2007 show in New York City, who had known Hayes fairly well, reported that "Isaac was plunked down at a keyboard, where he pretended to front his band. He spoke-sang, and his words were halting. He was not the Isaac Hayes of the past."[34]

In April 2008, while a guest on The Adam Carolla Show, Hayes stumbled in his responses to questions, possibly as a result of health problems. A caller questioned whether Hayes was under the influence of a substance, and Carolla and co-host Teresa Strasser asked Hayes if he had ever used marijuana. After some confusion on what was being asked, Hayes replied that he had only ever tried it once. During the interview the radio hosts made light of Hayes's awkward answers, and replayed snippets of earlier ones to simulate conversation with his co-hosts. Hayes stated during this interview that he was no longer on good terms with Parker and Stone.[35]

During the spring of 2008, Hayes shot scenes for Soul Men, a comedy inspired by the history of Stax Records, in which he appears as himself in a supporting role. The film was released in November 2008, after both Hayes and his costar, Bernie Mac, had died.[36]

Health problems and death

editOn March 20, 2006, Roger Friedman of Fox News reported that Hayes had suffered a minor stroke in January.[31] Hayes's spokeswoman, Amy Harnell, denied this,[37] but on October 26, 2006, Hayes confirmed he had suffered a stroke.[38]

On August 10, 2008, at the age of 65, Hayes was found unresponsive in his home, just east of Memphis, as reported by the Shelby County, Tennessee Sheriff's Office.[39] A Shelby County Sheriff's deputy and an ambulance from Rural Metro responded to his home after three family members found his body on the floor next to a still-operating treadmill. Hayes was taken to Baptist Memorial Hospital in Memphis, where he was pronounced dead at 2:08 p.m.[39][40][41] The cause of death was not immediately clear,[42] although the area medical examiners later listed a recurrence of stroke as the cause of death.[41][43] Hayes was buried at Memorial Park Cemetery, in Memphis, Tennessee.[44]

Legacy

editThe Tennessee General Assembly enacted legislation in 2010 to honor Hayes by naming a section of Interstate 40 the "Isaac Hayes Memorial Highway." The name was applied to the stretch of highway in Shelby County from Sam Cooper Boulevard in Memphis east to the Fayette County line. The naming was made official at a ceremony held on Hayes's birth anniversary in August 2010.[45]

Personal life

editFamily

editHayes had 11 children, 14 grandchildren, and three great-grandchildren.[46] His first marriage was to Dancy Hayes in 1960 and ended in divorce.[47] His second marriage was to Emily Ruth Watson on November 24, 1965, which ended in divorce in 1972. Children from this marriage included Vincent Eric Hayes, Melanie Mia Hayes, and Nicole A. Hayes (Murrell). He married bank teller[citation needed] Mignon Harley on April 18, 1973, and they divorced in 1986; they had two children. Hayes and his wife were eventually forced into bankruptcy, owing over $6 million. Over the years, Isaac Hayes was able to recover financially.[48]

Hayes's fourth wife, Adjowa,[49] gave birth to a son named Nana Kwadjo Hayes on April 10, 2006.[50] He also had one son to whom he gave his name, Isaac Hayes III, known as rap producer Ike Dirty. Hayes's eldest daughter is named Jackie, also named co-executor of his estate, and other children include Veronica, Felicia, Melanie, Nikki, Lili, Darius, Vincent[51] and Heather.[52]

Scientology

editHayes took his first Scientology course in 1993,[53] later contributing endorsement blurbs for many Scientology books over the ensuing years. In 1996, Hayes began hosting The Isaac Hayes and Friends Radio Show on WRKS in New York City. While there, Hayes became a client of the vegan raw food chef Elijah Joy and his company Organic Soul Inc. Hayes also appears in the Scientology film Orientation. In 1998, Hayes and fellow Scientologist entertainers Anne Archer, Chick Corea and Haywood Nelson attended the 30th anniversary of Freedom Magazine, the Church of Scientology's self-described investigative news journal, at the National Press Club in Washington, D.C., to honor eleven activists.[54] In 2001, Hayes and Doug E. Fresh, another Scientologist musician, recorded a Scientology-inspired album called The Joy of Creating – The Golden Era Musicians and Friends Play L. Ron Hubbard.[55]

Charitable work

editThe Isaac Hayes Foundation was founded in 1999 by Hayes.[56] In February 2006, Hayes appeared in a Youth for Human Rights International music video called "United". YHRI is a human rights group founded by the Church of Scientology-backed non-profit United for Human Rights. He was also involved in other human rights related groups such as the One Campaign. Isaac Hayes was crowned a chief in Ghana for his humanitarian work and economic efforts on the country's behalf.[57]

Discography

edit- Presenting Isaac Hayes (1968)

- Hot Buttered Soul (1969)

- The Isaac Hayes Movement (1970)

- ...To Be Continued (1970)

- Shaft (1971)

- Black Moses (1971)

- Live at the Sahara Tahoe (1973)

- Joy (1973)

- Truck Turner (1974)

- Chocolate Chip (1975)

- Disco Connection (1975)

- Groove-A-Thon (1976)

- Juicy Fruit (Disco Freak) (1976)

- New Horizon (1977)

- Hotbed (1978)

- For the Sake of Love (1978)

- Don't Let Go (1979)

- And Once Again (1980)

- Lifetime Thing (1981)

- U-Turn (1986)

- Love Attack (1988)

- Raw & Refined (1995)

- Branded (1995)

Collaborations

editWith Otis Redding

- Otis Blue: Otis Redding Sings Soul (Volt, 1965)

- The Soul Album (Volt, 1966)

- Complete & Unbelievable: The Otis Redding Dictionary of Soul (Volt, 1966)

- King & Queen (Stax, 1967)

- The Dock of the Bay (Volt, 1968)

With Wilson Pickett

- The Exciting Wilson Pickett (Atlantic, 1966)

With Donald Byrd and 125th Street, N.Y.C.

- Love Byrd (Elektra, 1981)

- Words, Sounds, Colors and Shapes (Elektra, 1982)

With Linda Clifford

- I'm Yours (Curtom/RSO, 1980)

With Albert King

- Born Under a Bad Sign (Stax, 1967)

With William Bell

- The Soul of a Bell (Stax, 1967)

With Dionne Warwick

- No Night So Long (Arista, 1980)

With Rufus Thomas

- Do The Funky Chicken (Stax, 1970)

With Eddie Floyd

- Knock on Wood (Stax, 1967)

Filmography

edit| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1973 | Wattstax | Himself | |

| 1973 | Save the Children | Himself | |

| 1974 | Three Tough Guys | Lee | |

| Truck Turner | Mac "Truck" Turner | ||

| 1976 | It Seemed Like a Good Idea at the Time | Moriarty | |

| 1976–1977 | The Rockford Files | Gandolph Fitch | TV, 3 episodes |

| 1981 | Escape from New York | The Duke | |

| 1985 | The A-Team | C.J. Mack | TV, 1 episode |

| 1986 | Hunter | Jerome "Typhoon" Thompson | TV, 1 episode |

| 1987 | Miami Vice | Holiday | TV, 1 episode |

| 1988 | I'm Gonna Git You Sucka | Hammer | |

| 1990 | Fire, Ice and Dynamite | Hitek Leader/Himself | Alternative title: Feuer, Eis und Dynamit |

| 1991 | Guilty as Charged | Aloysius | |

| 1993 | CB4 | Owner | |

| Posse | Cable | ||

| Robin Hood: Men in Tights | Asneeze | ||

| American Playhouse | Prophet | TV, 1 episode | |

| Acting on Impulse | Cameo role | ||

| 1994 | It Could Happen to You | Angel Dupree | |

| Tales from the Crypt | Samuel | TV, 1 episode | |

| 1995 | The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air | Minister Hayes | TV, 1 episode |

| Soul Survivors | Vernon Holland | TV movie | |

| 1996 | Flipper | Sheriff Buck Cowan | |

| Sliders | The Prime Oracle | TV, 1 episode | |

| 1997 | Uncle Sam | Jed Crowley | |

| 1997–2006 | South Park | Chef (voice) | TV, 136 episodes |

| 1998 | Blues Brothers 2000 | Member of The Louisiana Gator Boys | |

| South Park | Chef (voice) | Video game | |

| 1999 | South Park: Chef's Luv Shack | Chef (voice) | Video game |

| South Park: Bigger, Longer & Uncut | Chef (voice) | ||

| The Hughleys | The Man | TV, 2 episodes | |

| 2000 | South Park Rally | Chef (voice) | Video game |

| Reindeer Games | Zook | ||

| Shaft | Uncredited | ||

| 2001 | Dr. Dolittle 2 | Possum (voice) | |

| 2002 | The Education of Max Bickford | "Night Train" Raymond | TV, 1 episode |

| Fastlane | Detective Marcus | TV, 1 episode | |

| 2003 | Book of Days | Jonah | TV movie |

| Girlfriends | Eugene Childs | TV, 2 episodes | |

| 2003 | Dream Warrior | Zo | |

| 2004 | Anonymous Rex | Elegant Man | |

| 2005 | Hustle & Flow | Arnel | |

| Bernie Mac Show | Himself | ||

| 2006 | That '70s Show | Himself | TV, 1 episode |

| Stargate SG-1 | Tolok | TV, 4 episodes | |

| 2008 | Soul Men | Himself | Released posthumously |

| Kill Switch | Coroner | Released posthumously | |

| Return to Sleepaway Camp | Charlie | Released posthumously | |

| 2014 | South Park: The Stick of Truth | Chef (voice) | Video game; archival recordings |

Awards and nominations

editReferences

edit- ^ Planer, Lindsay (n.d.). "Black Moses – Isaac Hayes". AllMusic. Retrieved January 28, 2021.

- ^ Gibron, Bill (August 10, 2008). "Funk Soul Brother: Isaac Hayes (1942–2008)". PopMatters. Retrieved January 28, 2021.

- ^ Farber, Jim (February 20, 2018). "'I didn't give a damn if it didn't sell': how Isaac Hayes helped create psychedelic soul". The Guardian. Retrieved January 28, 2021.

- ^ Booth, Stanley (February 8, 1969). "The rebirth of the blues: Soul". The Saturday Evening Post. pp. 26–31, 60–61.

- ^ "Isaac Hayes | Rock & Roll Hall of Fame". Archived from the original on October 8, 2016. Retrieved August 17, 2014.

- ^ "Celebrating Isaac Hayes, the philanthropic musician who was crowned king in Ghana". Face2faceafrica.com. August 10, 2018. Retrieved February 23, 2021.

- ^ "BMI Celebrates Urban Music at 2003 Awards Ceremony". bmi.com. August 5, 2003. Retrieved October 2, 2010.

- ^ "Soul King Isaac Hayes Dead at 65". bmi.com. August 11, 2008. Retrieved October 2, 2010.

- ^ "Isaac Hayes – Biography | Billboard". Billboard.com.

- ^ "Isaac Hayes Biography (1942–)". Filmreference.com. Archived from the original on April 2, 2016.

- ^ a b Holley, Joe (August 11, 2008). "Isaac Hayes; Created Memphis Sound, 'Theme From Shaft'". Washingtonpost.com. Retrieved September 11, 2010.

- ^ Bowman 1997, p. 53.

- ^ "Isaac Hayes". staxrecords.com. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- ^ Howe, Sean (November 15, 2017). "Meet the Musicians Who Gave Isaac Hayes His Groove (Published 2017)". The New York Times. Retrieved February 23, 2021.

- ^ a b "Ultimate Isaac Hayes (Can You Dig It?), Audio Archived June 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine". Contactmusic.com. Retrieved March 15, 2008.

- ^ "RIP Isaac Hayes". Perthetic.wordpress.com. August 12, 2008. Retrieved September 11, 2010.

- ^ a b c Isaac Hayes Discography Archived August 4, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, staxrecords.free.fr; retrieved March 15, 2008.

- ^ MusicStack Archived March 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine entries for In the Beginning show that the LP's contents are identical to those of Presenting Isaac Hayes.

- ^ Isaac Hayes Billboard chart history. Allmusic.com; retrieved March 15, 2008.

- ^ Bowman 1997, pp. 332–334.

- ^ "Memphis Sounds". Remember the ABA. Archived from the original on June 3, 2021. Retrieved July 24, 2021.

- ^ "Memphis Sounds". Remember the ABA. Archived from the original on October 19, 2015. Retrieved September 11, 2010.

- ^ Bowman 1997, p. 334.

- ^ "Isaac Hayes interview by Pete Lewis, 'Blues & Soul' May 1995". Bluesandsoul.com. August 10, 2008. Retrieved September 11, 2010.

- ^ "Chef Aid: The South Park Album (Television Compilation) [Extreme Version]: Darren Mitchell, James Hetfield, Marc Shaiman, Matt Stone: Music". Amazon. Retrieved September 11, 2010.

- ^ "Chef – Character Guide – South Park Studios". Southparkstudios.com.[dead link]

- ^ "Featured Artists from the Official UK Charts Company". Theofficialcharts.com. Archived from the original on February 21, 2006. Retrieved September 11, 2010.

- ^ A.V. Club interview of Isaac Hayes Archived October 25, 2006, at the Wayback Machine, January 4, 2006.

- ^ "Isaac Hayes quits 'South Park' citing religious intolerance". CBC. March 23, 2006. Archived from the original on March 14, 2007.

- ^ "South Park gets revenge on Chef". BBC News. March 23, 2006.

- ^ a b Roger Friedman (March 20, 2006). "Chef's Quitting Controversy". Fox News. Archived from the original on October 16, 2006. Retrieved December 7, 2018.

- ^ Parker, Ryan (September 14, 2016). "Holy Shit, 'South Park' Is 20! Trey Parker, Matt Stone on Censors, Tom Cruise and Scientology's Role in Isaac Hayes Quitting". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved September 15, 2016.

- ^ "The top 10 ballsiest South Park episodes". Denofgeek.com. September 30, 2015.

- ^ a b Roger Friedman, "Isaac Hayes's History With Scientology" Archived March 20, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, Fox News, August 11, 2008

- ^ Isaac Hayes interview, MP3 format Archived October 28, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, FreeFM: The Adam Carolla Show, April 9, 2008

- ^ Swan, Lisa (August 11, 2008). "Both Bernie Mac and Isaac Hayes appear in 'Soul Men'". New York Daily News. Retrieved November 9, 2021.

- ^ Hayes Slams 'Stroke' Rumors Archived June 5, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Hollywood.com, March 27, 2006

- ^ Hayes has put stroke, 'South Park' behind him, MySanAntonio.com, October 26, 2006. Archived July 20, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "Memphis soul legend Isaac Hayes dead at 65". Action News 5. August 10, 2008. Archived from the original on January 15, 2009. Retrieved September 11, 2010.

- ^ Levine, Doug (August 11, 2008). "Singer, Songwriter Isaac Hayes Dies". VOA News. Voice of America. Archived from the original on December 14, 2008. Retrieved January 3, 2009.

- ^ a b "Soul legend Isaac Hayes dies". CNN. August 10, 2008. Retrieved August 10, 2008.

- ^ Oscar-Winning Singer Isaac Hayes Dead: "Hot Buttered Soul" Made Him Famous Four Decades Ago, "Theme From Shaft" Won Prestigious Awards . CBS News. Retrieved August 12, 2008.

- ^ "Stroke killed singer Isaac Hayes". BBC News. August 13, 2008. Retrieved September 11, 2010.

- ^ "Soul legend Isaac Hayes' grave marker unveiled in Memphis". WMC-TV. August 23, 2009.

- ^ Bob Mehr (August 20, 2010). "I-40 stretch named for Memphis music star Isaac Hayes". Commercial Appeal. Memphis, Tennessee.

- ^ You Can Dig Him [dead link], Chattanooga Pulse, December 13, 2006

- ^ "Isaac Hayes Biography (1942–)". Filmreference.com. Retrieved September 11, 2010.

- ^ "Old School Tidbits". Panache Report. Retrieved September 11, 2010.

- ^ ISAAC HAYES AND ADJOWA HAYES, beliefnet.com Archived September 2, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Isaac Hayes the Father of Baby Boy Archived April 11, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, AP, May 16, 2006

- ^ "Isaac Hayes Sent Off With Legendary Funeral". Actressarchives.com. August 19, 2008. Archived from the original on December 22, 2008. Retrieved September 11, 2010.

- ^ "The Kevin Ross Show – Isaac Hayes His Children Record Label Reflect On A Musical Giant 8/13/2008 – 3BAAS Media Group | Internet Radio". Blog Talk Radio. August 14, 2008. Retrieved September 11, 2010.

- ^ "Biography". Isaac Hayes. Archived from the original on June 20, 2012. Retrieved March 1, 2013.

- ^ Kennedy, James (October 23, 1998). "Haywood You Remember Garden City Park". Mineola American, Anton Community Newspapers. Archived from the original on July 7, 2011. Retrieved July 27, 2010.

- ^ Leggett, Jonathan (March 25, 2006). "Cult musicians". The Guardian. London.

- ^ "charity". Isaac Hayes.com. Archived from the original on July 13, 2011. Retrieved September 11, 2010.

- ^ Day, Echo. "Seven things to know about the legendary Isaac Hayes". Covingtonleader.com. Archived from the original on May 28, 2019. Retrieved May 28, 2019.

- ^ "The 44th Academy Awards (1972) Nominees and Winners". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Retrieved August 26, 2011.

- ^ "American Music Awards – Winner Database (1979)". American Music Awards. Retrieved February 28, 2023.

- ^ "BAFTA Awards: Film in 1972". British Academy Film Awards. Retrieved September 16, 2016.

- ^ "Isaac Hayes". Golden Globe Awards. Retrieved February 28, 2023.

- ^ "Isaac Hayes". Grammy Awards. Retrieved February 28, 2023.

- ^ "Film Hall of Fame: Scores". Online Film & Television Association. Retrieved February 28, 2023.

- ^ "The 12th Annual Screen Actors Guild Awards". Screen Actors Guild Awards. Retrieved May 21, 2016.

Bibliography

edit- Bowman, Rob (1997). Soulsville U.S.A.: The Story of Stax Records. New York: Schirmer Trade. ISBN 978-0-8256-7284-2. OCLC 36824884. Google Books.