Innocent Sinners is a 1958 British black and white film directed by Philip Leacock and starring Flora Robson, David Kossoff and Barbara Mullen.[1]

| Innocent Sinners | |

|---|---|

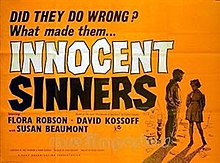

British theatrical poster | |

| Directed by | Philip Leacock |

| Screenplay by | Neil Paterson Rumer Godden |

| Based on | novel An Episode of Sparrows by Rumer Godden |

| Produced by | Hugh Stewart |

| Starring | Flora Robson David Kossoff Susan Beaumont |

| Cinematography | Harry Waxman |

| Edited by | John D. Guthridge |

| Music by | Philip Green |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | J. Arthur Rank Film Distributors (UK) |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 95 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

It was based on the 1955 novel An Episode of Sparrows by Rumer Godden.[2]

Plot

editOlivia Chesney is too ill to leave her home in a post-war London square, but waves out of her window to various neighbours. These include Lovejoy, who is a neglected young girl who finds solace in the secret garden which she creates on a bomb site. Lovejoy buys grass seed using borrowed money, and steals a net from a baby's pram to use to protect the seed growing. She also steals money from the candle box in the church in order to buy a garden fork.

Lovejoy is being looked after by the Vincents. Mr Vincent is the waiter in his own posh restaurant and is very kind to Lovejoy. Her mother is an actress away on tour, and seems to have a dubious lifestyle when she visits Lovejoy; she has "male callers" such as Colonel Baldcock who Lovejoy is asked to address as "Uncle Francis". Mr Vincent is unhappy with her lifestyle and asks her to leave.

A gang of young boys destroy Lovejoy's garden. One boy, Tip, returns her garden fork to her and suggests a better site: a bombed out church. They become friends. He makes her pay "penance" for stealing money from the church.

Mr Vincent buys two special plates to serve dessert on, but his wife chastises him, as they have bills to pay.

Meanwhile a wealthy couple have plans for the bombed church. The woman gives Lovejoy a shilling in the church and is impressed when she puts it straight into the candle box as part of her penance. The couple go to Vincent's restaurant to eat. They give Lovejoy a ride in their car and give her a miniature rose to plant in her garden.

An old man gives Lovejoy some seedlings as it is too late to plant seeds. Tip steals earth from the local private garden square, much to the annoyance of the adults.

On a rainy night Tip brings Lovejoy and a small boy, Sparkey, to the park to steal more earth. Lovejoy gets arrested with the boys. The police are aware that Lovejoy's mother is not around; in fact, she has gone to Canada and got married but has no plans for Lovejoy to follow her.

The Vincents get into serious financial trouble and have to give Lovejoy away to the Home of Compassion care home. Lovejoy appeals to Olivia to help. Olivia regrets having made little use of her life, and decides to write a will setting up a trust to open a new restaurant in the West End, to be run by the Vincents, on condition they look after Lovejoy.

The bombed church is pulled down, and Lovejoy leaves the care home to rescue her rose. Olivia dies before signing the will, so that her sister Angela would inherit her money. Lovejoy leaves her rose at Olivia's house to be looked after by her, not knowing of her death. Angela is deeply moved, and decides to proceed with her sister's wishes for the trust. Lovejoy goes to live with Vincents, and they start preparing for the new restaurant.

Cast

edit- June Archer as Lovejoy Mason

- Christopher Hey as Tip Malone

- Brian Hammond as Sparkey

- Flora Robson as Olivia Chesney

- David Kossoff as George Vincent

- Barbara Mullen as Mrs. Vincent

- Catherine Lacey as Angela Chesney

- Susan Beaumont as Liz

- Lyndon Brook as Charles

- Edward Chapman as Manley

- John Rae as Mr. Isbister

- Vanda Godsell as Bertha Mason - Lovejoy's Mother

- Hilda Fenemore as Cassie

- Pauline Delaney as Mrs. Malone

- Andrew Cruickshank as Dr. Lynch-Cliffe

- Cyril Chamberlain as Colonel Francis Baldock (uncredited)

- Basil Dignam as Mr. Dyson - Olivia's Solicitor (uncredited)

- William Squire as Father Lambert (uncredited)

- Marianne Stone as Sparkey's Mother (uncredited)

- Toke Townley as Bates (uncredited)

Production

editHugh Stewart, the producer, said he made the film because "I loved the story' although he had to change the title because "the studio wouldn’t have a project with a title like that." Neil Paterson wrote the script, which Hugh Stewart said "was very difficult because Rumer Godden’s story was very gossamer, and I was trying to get some bones in it. She hated what Neil did." He was "very pleased" with Philip Leacock as director.[3]

Leacock had made a number of films featuring children including The Kidnappers and The Spanish Garden. He used amateurs to play the children rather than actors, saying "untrained children are not always suitable for a film but for this particular story I felt it was essential to have absolutely ordinary children."[4]

Philip Leacock later said "I don't know why they changed the title... it hurt it because it was a well known novel, you know. And the Rank Organisation didn't think 'Episode of Sparrows' would mean anything and in those days - well they still are - they're so ridiculous about titles. But I think it hurt the picture. "[5]

Reception

editStewart said "It was the one film I made that got universally good notices, it got prizes, and yet it died a death — the biggest disaster I ever had... The critics, like Paul Dehn, went overboard for it: it really got under their skin."[3]

Sight and Sound called it "a well-meaning, uneven and somewhat meandering film" where "a string of sub-plots, although relevant, never quite come coherently together." The critic felt "the children’s scenes are by far the firmest, well played... and directed with delicate care. The adults... stand oddly apart and their playing, by contrast, appears not a little confected. The weakest aspect of the film, though, is its inability to bring to life its background—the dirty, overcrowded London suburb, where busy working-class streets adjoin an upper-class area of tree-lined walks and squares. A weird mixture of location material (Battersea and Victoria) hardly helps here. Despite these flaws, though, Innocent Sinners has a kind of awkward sincerity about it: it is a film whose intentions go beyond its achievement."[6]

Rich. of Variety said it was "a half-hearted stab at being a tearjerker, but it barely tugs at the emotions. With no real star value in its work-manlike cast, chances of survival in the boxoffice jungle are slim."[7]

The Evening Standard called it "fresh, funny and moving."[8]

References

edit- ^ "Innocent Sinners (1958)". Archived from the original on 10 March 2016.

- ^ Goble, Alan (1 January 1999). The Complete Index to Literary Sources in Film. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 9783110951943 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b McFarlane, Brian (1997). An autobiography of British cinema : as told by the filmmakers and actors who made it. p. 547.

- ^ "Back Street 'Stars'". Lincolnshire Echo. 25 March 1958. p. 4.

- ^ Peet, Stephen (1987). "Interview with Philip Leacock" (PDF). British Entertainment History Project.

- ^ Cutts, John (April 1958). "Innocent Sinners". Sight and Sound. p. 203.

- ^ Rich. (2 April 1958). "Innocent Sinners". Variety. p. 16.

- ^ "The dream that grew in a bomb-iste garden". Evening Standard. 20 March 1958. p. 6.

External links

edit