The current Indianapolis Masonic Temple, also known as Indiana Freemasons Hall, is a historic Masonic Temple located at Indianapolis, Indiana. Construction was begun in 1908, and the building was dedicated in May 1909. It is an eight-story, Classical Revival style cubic form building faced in Indiana limestone. The building features rows of engaged Ionic order columns.[2] It was jointly financed by the Indianapolis Masonic Temple Association and the Grand Lodge of Free and Accepted Masons of Indiana, and was designed by the distinguished Indianapolis architectural firm of Rubush and Hunter.

Indianapolis Masonic Temple (aka Indiana Freemasons' Hall) | |

The Indianapolis Masonic Temple is the statewide headquarters of the Grand Lodge of Free and Accepted Masons of Indiana. | |

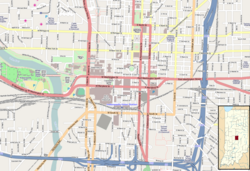

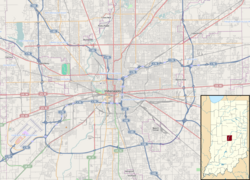

| Location | 525 N. Illinois Street, Indianapolis, Indiana |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 39°46′38″N 86°9′33″W / 39.77722°N 86.15917°W |

| Area | less than one acre |

| Built | 1908 |

| Architect | Rubush & Hunter |

| Architectural style | Classical Revival |

| NRHP reference No. | 08000193[1] |

| Added to NRHP | March 19, 2008 |

The Indianapolis Masonic Temple is the statewide headquarters of the Grand Lodge F&AM of Indiana, and home to numerous individual Masonic lodges and associated groups. It is also the location of the Masonic Library and Museum of Indiana; the Indiana Masonic Home Foundation; Indiana DeMolay, and many more. The building features an auditorium, two stages, a large dining hall and catering kitchen, a ballroom, and seven large lodge rooms designed for a variety of ceremonial and social purposes.

History

editThe Freemasons of Indianapolis had previously built two other jointly owned temples in Indianapolis in partnership with the Grand Lodge. Those stood on the southeast corner of Washington Street and Capitol Avenue (formerly Tennessee Street) and diagonally across from the Indiana Statehouse. The Hyatt Regency Indianapolis Hotel currently stands at that site. The current Temple is the third such building in Indianapolis.

Indianapolis Masonic Hall of 1850

editThe first joint Masonic temple in the city, a colonnaded Greek Revival hall, was built in 1850.[citation needed] The building was the site of the Indiana Constitutional Convention of 1850 that met to draft a new state constitution. The state government rented the Masonic temple for the gathering because the House of Representative in the Indiana Statehouse was too small to accommodate the 150 convention delegates.[3]

A reporter for the Locomotive Magazine sardonically described the convention scene on February l, 1851:[4]

The chandeliers, you observe, these three big dark green things, like great dropsical spiders, swinging by gigantic cobwebs from the ceiling—are too clumsy, too low down, and really disfigure the Hall. Those red settees, and cross-legged poplar tables, like foldup cots, only not so clean, arranged with aisles between, for the convenience of approach, and whittled and inked all over like school-boys desks, are the member’s seats, and stands—where the members write if they happen to be taken industrious. . . . Those seats along the east wall are often full of ladies, when the Convention is in session, and it then looks like an oblong dirty apron, with a bright border down one side.

Along with its intended role as a meeting and ceremonial space for the city's Freemasons, the hall's main auditorium became the first large-scale venue in the city for speakers, entertainers, debates and presentations. Despite Freemasonry's strict rules forbidding the discussion of politics in their meetings, such restrictions did not extend to the use of their auditorium. In 1853, the Masonic Hall hosted fiery demonstrations and presentations by the city's black leaders and white anti-slavery speakers in opposition to the Fugitive Slave Act. The events were touched off by charges leveled against John Freeman, an Indianapolis house painter wrongfully accused of being a runaway slave.[5]

On September 19, 1859, Abraham Lincoln gave a speech at the Temple (the second of three he ultimately made in Indianapolis during his career). He opened his political remarks by recalling his famous words: “This government cannot endure permanently, half slave and half free; that a house divided against itself cannot stand.”[6]

Indianapolis Masonic Hall of 1875

editThe first temple suffered from serious construction defects and was demolished in 1873. It was replaced by an imposing red-brick Romanesque structure on the same corner, officially opened in 1875. The second temple was designed with ample rental space on the first two floors to generate income. Renters would eventually include a cleaners and a Turkish bath, along with several offices.[7] There were ceremonial and social rooms for five Masonic lodges on the upper floors. However, late in the design process it was noted with great alarm by the state's Masons that the architects had neglected to create an appropriately large meeting hall for the annual meetings of hundreds of lodge officers each year. The Grand Lodge was forced to hurriedly purchase an adjoining lot immediately to the south to attach an architecturally incongruous assembly hall to the backside of the building. After an initial estimate of under $70,000, the total cost of the project was $120,000. The embarrassing errors and cost overruns, combined with the great economic Panic of 1873 nearly bankrupted the Grand Lodge.

Indianapolis Masonic Temple of 1909

editThe Masons and the economy eventually rebounded, and by 1900 there were eight Indianapolis Masonic lodges and numerous appendant groups that had filled the second building beyond its designed capacity. Following a devastating fire in the second temple in 1905, it was determined that a new building at a different location needed to be constructed.

Elias J. Jacoby, an attorney and insurance executive, and a very prominent Mason, helped found the Indianapolis Masonic Temple Association and chaired its building committee. The committee hired the firm of Rubush & Hunter, which has been called "the premier Indianapolis architectural firm of the early 20th Century", to design the new structure. The firm, headed by Indiana natives Preston C. Rubush and Edgar O. Hunter, were largely responsible for the look of Indianapolis during this period of the city's history, at the height of the City Beautiful movement. They constructed the new building from Bedford limestone in the Greek-Ionic style. It is over 100 feet (30 m) tall and measures 130 by 150 feet (40 m × 46 m) at ground level. The original cost of construction was $531,000. On the first floor is what was originally an 1100-seat auditorium which, due to neglect after the 1960s, lay virtually unused for over forty years until its renovation in 2005. During its heyday, the Hall hosted speakers, concerts, political candidates from all parties, debates, movies, and even new citizen swearing-in ceremonies. By 1963, Indiana Masons had outgrown the auditorium and moved their annual meetings across the street into the larger (and air-conditioned) Indianapolis Scottish Rite Cathedral. Because of seating modifications and the closure of the balcony, the Hall's current capacity has been reduced to about 600.

Also on the first floor is the headquarters of the Grand Lodge of Indiana, and the Indiana Masonic Home Foundation. A large banquet hall is located on second floor and is available for wedding receptions, business meetings and other events. The Masonic Library and Museum of Indiana, once housed at Compass Park in Franklin, Indiana, is located on the fifth floor of the Temple building and is open to the public at irregular hours.

While many of the Masonic lodge meeting rooms look very similar, the seventh floor is dedicated to the York Rite appendant organizations. It features a large Knights Templar asylum with gallery seating areas and open floorspace for marching in formation; an arched Royal Arch Chapter Room and 'secret vault' area; and a small Red Cross Room that is decorated in a unique Egyptian revival motif with murals and custom furniture original to the building.

At the time of its construction the Temple held seven separate pipe organs, of which six survive and remain operable. In 1919, there were 1,174 meetings held in the Temple. More than 41,000 meals were served that year, with thirty-six banquets held in December alone.[7]

During World War II, the south end of the basement was converted for use as a Masonic Service Club, a social and recreational area for members of the armed forces, with pool tables, a snack bar, writing desks, and a library of national newspapers–similar to a USO club. Area Masons, women from the auxiliary groups like the Order of the Eastern Star, and teenaged members of the Masonic youth groups like Rainbow Girls and Jobs Daughters volunteered to staff the club 24 hours a day.[7]

Even the rooftop was designed for active use. Originally covered in tile, the rooftop was used for drill team practice by the Knights Templar, as well as open air parties and dinners with a view of the city. Today it is largely covered with cell phone towers and is largely inaccessible.

The Temple was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2008.[2] It is also listed in the Indiana Register of Historic Sites and Structures.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ a b "Indiana State Historic Architectural and Archaeological Research Database (SHAARD)" (Searchable database). Department of Natural Resources, Division of Historic Preservation and Archaeology. Retrieved 2016-08-01. Note: This includes Glory-June Greiff (August 2007). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form: Indianapolis Masonic Temple" (PDF). Retrieved 2016-08-01. and Accompanying photographs

- ^ Dunn, Jacob Piatt (1919). Indiana and Indianans: A History of Aboriginal and Territorial Indiana and the Century of Statehood. Vol. 1. Chicago and New York: The American Historical Society. pp. 442–43. OCLC 2470354.

- ^ Sulgrove, Barry (writing as "Timothy Tugmutton") (1884). "The Locomotive Magazine". History of Indianapolis and Marion County, Indiana [Philadelphia, 1884], p. 256.

- ^ Burlock, Melissa (2014-07-22). "9 Weeks a Fugitive Slave: The 1853 Fugitive Slave Case of Mr. John Freeman". Hoosier State Chronicles: Indiana's Digital Newspaper Program. Retrieved 2019-07-12.

- ^ Lighty, S. Chandler (September 15, 2016). "Lincoln's Forgotten Visit to Indianapolis". Indiana History Blog. Retrieved July 7, 2019.

- ^ a b c Hodapp, Christopher L. (2018). Heritage endures : perspectives on 200 years of Indiana freemasonry. Freemasons. Grand Lodge of Indiana. Indianapolis. pp. 213–14. ISBN 9781513629025. OCLC 1042088156.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

Further reading

edit- McDonald, Daniel (1898). A History of Freemasonry in Indiana from 1806 to 1898. Indianapolis: Grand Lodge F&AM of Indiana.

- Smith, Dwight L. (1968). Goodly Heritage. Indianapolis: Grand Lodge F&AM of Indiana. ISBN 978-1387819928.

- Hodapp, Christopher (2018). Heritage Endures: Perspectives on 200 Years of Indiana Freemasonry. Indianapolis: Grand Lodge F&AM of Indiana. ISBN 9781513629025.

External links

edit- William H. Smythe (Grand Secretary of the M. W. Grand Lodge of the State of Indiana) (1898). Indiana Masonic law and forms of procedure for the use of Freemansons [sic] and Masonic lodges. Indianapolis: Sentinel Printing Co. p. 328. Archived from the original on October 24, 2018. Retrieved October 24, 2018 – via archive.org.