Incisoscutum is an extinct genus of arthrodire placoderm from the Early Frasnian Gogo Reef, from Late Devonian Australia. The genus contains two species I. ritchiei,[1] named after Alex Ritchie, a palaeoichthyologist and senior fellow of the Australian Museum, and I. sarahae, named after Sarah Long, daughter of its discoverer and describer, John A. Long.

| Incisoscutum Temporal range: Late Devonian: Frasnian,

| |

|---|---|

| |

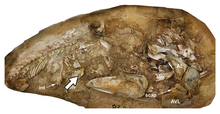

| Incisoscutum specimen WAM 03.3.28 | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | †Placodermi |

| Order: | †Arthrodira |

| Suborder: | †Brachythoraci |

| Clade: | †Eubrachythoraci |

| Clade: | †Coccosteomorphi |

| Superfamily: | †Incisoscutoidea |

| Family: | †Incisoscutidae |

| Genus: | †Incisoscutum Dennis & Miles, 1981 |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The genus is important in the study of early vertebrates as well-preserved fossilized embryos have been found in female specimens[2] and ossified pelvic claspers found in males.[3] This shows that viviparity and internal fertilization was common amongst these primitive jawed vertebrates, which are outside the crown group Gnathostomata.

In a study of fossil remains, comparison of the ontogeny of fourteen dermal plates from Compagopiscis croucheri and the more derived species Incisoscutum ritchiei suggested that lengthwise growth occurs earlier in the ontogeny than growth in width, and that dissociated allometric heterochrony has been an important mechanism in the evolution of the arthrodires, which include placoderms.[4]

Fossils

editThree-dimensional uncrushed Incisioscutum fossils with remarkable soft tissue preservation were discovered within the Western Australian Gogo Formation, a warm, shallow-sea reef facies of Frasnian age.[5] I. ritchiei was a small placoderm with an estimated body length of 30.3 cm (11.9 in).[6]

Palaeobiology

editFeeding and social behavior

editIncisoscutum's body size and morphology are similar to Torosteus and Compagopiscis, suggesting a possible pelagic lifestyle, although they were on different trophic levels of their ecosystem.[7] Jaw morphology suggests that Incisoscutum was durophagous, and individual fossils have been found in numbers, suggesting possible schooling behavior.[7]

Embryos

editWhen Incisoscutum ritchiei was first described, bony plates of smaller arthrodires were discovered within the body cavity of two specimens. Due to their disorganized arrangement, posterior position behind the trunk shield, apparent gastric etching and the fact that one of the small arthodires was posterior facing relative to the adult, these bony plates were thought to represent the stomach contents of the adult Incisoscutum.[1][2]

However, spurred by the discovery of preserved embryos inside the ptyctodonts Materpiscis attenboroughi [8] and Austroptyctodus gardineri, the ‘last meals’ of the Incisoscutum have now been reinterpreted as embryos, 5 cm in length, within pregnant adult females.[2]

The apparent gastric etching is now thought to be an early stage of ossification. The disarrangement is thought to be due to scattering as a result of the body cavity opening postmortem; worm casts throughout the body and surrounding matrix reveal that the fish carcass remained in an open environment after death. Furthermore, the lack of any taxa associated with the completely preserved delicate plates means that the arthrodires can now be excluded as stomach contents and interpreted as embryos.[2]

The discovery of embryos within Incisoscutum is of evolutionary importance as these fossils reveal that arthrodires had advanced reproductive biology and were able to give birth to live young. The Incisoscutum fossils show the oldest record of viviparity in any vertebrate, therefore internal fertilization and viviparity must have evolved in the vertebrates at least 380 million years ago and outside the gnathostomata.[2]

Viviparity in Incisoscutum and the ptyctodontids show that these placoderms were the first K-strategists in relation to breeding. They invested in rearing a smaller amount of eggs, rather than a huge spawn as their ancestors must have done. It is therefore likely that the warm reef environment of the Devonian Gogo Formation was stable and predictable, having a degree of ecological balance (for example hiding places for pregnant placoderms). This would have allowed the placoderms to invest more time and energy in producing and nurturing fewer, but more developed, offspring.[9]

Pelvic claspers

editSexually dimorphic pelvic claspers have been found in male and female Incisoscutum fossil specimens.[2][3] In males (WAM 03.3.28)[3] the completely ossified clasper is a slender rod attached to a square basal plate that articulates directly with the pelvic girdle. This contrasts to modern sharks where the clasper articulates with a basipterygial cartilage element. The tip of the distal end has a small cap of dermal bone with small pits and denticles for clinging on to the female. The proximal part of the clasper expands into a plate with four foramina, two larger above two smaller. It is thought that this anatomy corresponds to the core of an erectile element as in extant sharks.[3]

Female Incisoscutum specimens differ from these male claspers and instead fossils have been found with a broad based pelvic plate that articulates with a posteriorly directed basipterygium, similar to modern sharks. The distal end has an articulation for an additional cartilaginous segment or series.[2]

Therefore, the difference in pelvic claspers between genders suggests that sexual dimorphism was already present in the arthrodires in the Devonian. Pelvic claspers have also been discovered in pyctodontid fossils [8] suggesting homology. It is therefore suggested that pelvic claspers may characterize all of the pytodontids and arthrodires.[3] As males and females have never been found in the same locality, it is possible that Incisoscutum males and females inhabited different areas throughout most their life cycles, only coming together to mate, a behavior comparable to some extant sharks.[9]

Phylogeny

editIncisoscutum is a member of the superfamily Incisoscutoidea, which belongs to the clade Coccosteomorphi, one of the two major clades within Eubrachythoraci.[10][11] Incisoscutum was initially placed in the family Incisoscutidae. However, Incisoscutidae is currently a monotypic family, with the genus Incisoscutum as the only member, and thus the family name Incisoscutidae is not widely used.[10] Alternatively, Incisoscutum could possibly be considered a member of the closely related family Camuropiscidae, as shown in the cladogram below:[11]

| Eubrachythoraci |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

edit- ^ a b Kim Dennis; R.S. Miles (1981). "A pachyosteomorph arthrodire from Gogo, Western Australia". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 73 (3): 213–258. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1981.tb01594.x.

- ^ a b c d e f g John Long; Kate Trinajstic; Zerina Johanson (2009). "Devonian arthrodire embryos and the origin of internal fertilization in vertebrates". Nature. 457 (7233): 1124–1127. Bibcode:2009Natur.457.1124L. doi:10.1038/nature07732. PMID 19242474. S2CID 205215898.

- ^ a b c d e Per Ahlberg; Kate Trinajstic; Zerina Johanson; John Long (2009). "Pelvic claspers confirm chondrichthyan-like internal fertilisation in arthrodires". Nature. 460 (7257): 888–889. Bibcode:2009Natur.460..888A. doi:10.1038/nature08176. PMID 19597477. S2CID 205217467.

- ^ Trinajstic, Kate (1995). "The role of heterochrony in the evolution of eubrachythoracid arthrodires with special reference to Compagopiscis croucheri and Incisoscutum ritchei from the Late Devonian Gogo Formation, Western Australia". Geobios. 28 (Suppl. 2): 125–128. Bibcode:1995Geobi..28..125T. doi:10.1016/S0016-6995(95)80099-9.

- ^ John Long; Kate Trinajstic (2010). "The Late Devonian Gogo Formation lägerstatte of Western Australia: exceptional early vertebrate preservation and diversity". Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. 38: 255–279. Bibcode:2010AREPS..38..255L. doi:10.1146/annurev-earth-040809-152416.

- ^ Engelman, Russell K. (2023). "A Devonian Fish Tale: A New Method of Body Length Estimation Suggests Much Smaller Sizes for Dunkleosteus terrelli (Placodermi: Arthrodira)". Diversity. 15 (3). 318. doi:10.3390/d15030318.

- ^ a b Trinajstic, Kate; Briggs, Derek E. G.; Long, John A. (23 November 2021). "The Gogo Formation Lagerstätte: a view of Australia's first great barrier reef". Journal of the Geological Society. 179 (1). doi:10.1144/jgs2021-105. ISSN 0016-7649.

- ^ a b John Long; Kate Trinajstic; Gavin Young; Tim Senden (2008). "Live birth in the Devonian period". Nature. 453 (7195): 650–652. Bibcode:2008Natur.453..650L. doi:10.1038/nature06966. PMID 18509443. S2CID 205213348.

- ^ a b Long J. A., ed. (2012). The Dawn of the Deed. Illinois: University of Chicago Press. pp. 99–127. ISBN 9780226492544.

- ^ a b You-An Zhu; Min Zhu (2013). "A redescription of Kiangyousteus yohii (Arthrodira: Eubrachythoraci) from the Middle Devonian of China, with remarks on the systematics of the Eubrachythoraci". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 169 (4): 798–819. doi:10.1111/zoj12089.

- ^ a b Zhu, You-An; Zhu, Min; Wang, Jun-Qing (1 April 2016). "Redescription of Yinostius major (Arthrodira: Heterostiidae) from the Lower Devonian of China, and the interrelationships of Brachythoraci". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 176 (4): 806–834. doi:10.1111/zoj.12356. ISSN 0024-4082.