Ilse Bing (23 March 1899 – 10 March 1998) was a German avant-garde and commercial photographer who produced pioneering monochrome images during the inter-war era.

Ilse Bing | |

|---|---|

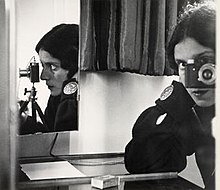

Self portrait in 1931 | |

| Born | 23 March 1899 |

| Died | 10 March 1998 (aged 98) |

| Nationality | German |

| Occupation | Photographer |

| Spouse | |

Biography

editBackground and early life

editBing was born to a wealthy Jewish family of Frankfurt merchants as the daughter of Louis Bing and his wife Johanna Elli Bing, nee. Katz.[1] At the age of 14, she was given a Kodak box camera, which she used to take her first self-portrait.[2] Bing began studying mathematics and physics at Frankfurt University in 1920, but shortly afterwards turned to art history and the history of architecture. She spent the winter semester of 1923/1924 at the Kunsthistorisches Institut Vienna.

In 1924, Bing began a dissertation on the architect Friedrich Gilly (1772-1800). The first photo works were created as part of this work after she bought her first camera, a Voigtländer (9x12cm), for documentation purposes.[3] It was during her time that Bing developed her lifelong interest in photography.[4] When she finished her studies in the summer of 1929 and gave up her dissertation, she turned entirely to photography, bought a newly launched Leica (35mm camera) and began working in photojournalism. For the next two decades, the Leica would remain the basis of Bing's artistic work.

Paris

editAt the end of 1930 Ilse Bing moved to Paris and continued her photographic work there. She received reportage assignments through the mediation of the Hungarian journalist Heinrich Guttmann. To develop her photos, Guttmann provided her with a garage that Bing used as a darkroom.[3]

Her move from Frankfurt to the burgeoning avant-garde and surrealist scene in Paris marked the start of the most notable period of her career.[4] She produced images in the fields of photojournalism, architectural photography, advertising and fashion, and her work was published in magazines such as Le Monde Illustre, Harper's Bazaar, and Vogue.[1] After initially living in the Hotel Londres on Rue Bonaparte, she moved to Avenue de Maine, 146 in 1931. In the same year, Bing's work was exhibited in both France and Germany.[3] Her rapid success as a photographer and her position as the only professional in Paris to use an advanced Leica camera earned her the title "Queen of the Leica"[5] from the critic and photographer Emmanuel Sougez, whom she met in 1931. In 1933, Bing left Avenue de Maine and moved to Rue de Varenne, No. 8. With the pianist and music teacher Konrad Wolff, who lived in the same house, she was initially only known through his piano playing, which could be heard through the courtyard. A little later they would get to know each other personally and become a couple.

When Bing visited New York in 1936, she received the offer to work as a photographer for Life magazine, which she turned down in order not to be separated from Wolff, who lived in Paris.[6] In the same year, her work was included in the first modern photography exhibition held at the Louvre, and in 1937 she traveled to New York City where her images were included in the landmark exhibition "Photography 1839–1937" at the Museum of Modern Art.[5] Bing and Wolff married in November of the same year and moved to Boulevard Jourdan together in 1938.

Bing remained in Paris for ten years, but in 1940, when Paris was taken by the Germans during World War II, she and her husband who were both Jews, were expelled and interned in separate camps in the South of France. Bing spent six weeks in a camp in Gurs, in the Pyrenees, where she met Hannah Arendt.[7][8]

In an interview with the German photographer Herlinde Koelbl, Bing later said:

“A lot of people just call it internment camps because we weren't mistreated. I felt it was a concentration camp. To be separated from my husband, not knowing where he is, not knowing what is going on out in the world. (...) This bondage, the absolute lack of freedom and degradation. I always had a razor blade with me. I was determined not to let the Nazis intern me. Then I would have taken my life. But you can take a lot more than you think. It was worse than you could imagine and you could endure more than you thought possible.”[9]

After Wolff stood up for Bing's release at great expense, they managed to reach Marseille together. There they waited nine months for their visa to enter the USA. The Affidavit of Sponsorship required for this was issued by the author and journalist Hendrik Willem van Loon, whom Bing had already met in 1930.[10] In 1941, Bing and Wolff finally emigrated and settled in New York.[11]

New York

editIn New York, Bing had to re-establish her reputation, and although she got steady work in advertising and portrait photography, she failed to receive important commissions as in Paris.[1]

When Bing and her husband fled Paris, she was unable to bring her prints and left them with a friend for safekeeping. Following the war, her friend shipped Bing's prints to her in New York, but Bing could not afford the custom fees to claim them all. Some of her original prints were lost when Bing had to choose which prints to keep.[12]

In the 1940s and 50s, Bing was best known for her portraits of children, but also photographed personalities such as Dwight D. Eisenhower and his wife Mamie.[13]

By 1947, Bing came to the realization that New York had revitalized her art. Her style was very different; the softness that characterized her work in the 1930s gave way to hard forms and clear lines, with a sense of harshness and isolation. This was indicative of how Bing’s life and worldview had been changed by her move to New York and the war-related events of the 1940s.[14]

Also in 1947, she went on a trip to Germany and France for the first time after the end of the war, visiting a.o. the war-torn Frankfurt and stayed in Paris for three months.[15] From 1950 Bing worked with a Rolleiflex, which she used in alternation with the Leica for the next two years, but in 1952 decided to work exclusively with the medium format of the Rolleiflex.[16]

In 1951 and 1952 she visited Paris again and always had her camera with her. In 1957 she turned away from black-and-white photography and concentrated on working with color negatives. In 1959, Bing decided to give up photography altogether. She felt the medium was no longer adequate for her, and seemed to have tired of it.[1] As a result, texts, collages, and drawings were created. She later said:

“I couldn't say anything new with this medium. I stopped working with the camera at the height of my photographic developments. I couldn't use it to express what I was experiencing. Of course, I could have taken nice pictures, but it no longer came from within. The character of the work changed with my development and has now been given a new face."[17]

In the mid-1970s, the Museum of Modern Art purchased and showed several of her photographs.[5] This show sparked renewed interest in Bing's work, and subsequent exhibitions included a solo show at the Witkins Gallery in 1976, and a traveling retrospective entitled, ''Ilse Bing: Three Decades of Photography,''[5][14] organized by the New Orleans Museum of Art. Numerous solo exhibitions followed in New York, Las Vegas, Chicago, San Francisco, Frankfurt, and many more.[18] Bing's photographs were also featured in multitudinous group exhibitions.

Bing published her first book in 1976 under the title Words as Visions at Ilkon. Press. Another publication with the title Numbers in Images followed in 1978 by the same publisher. In 1982 Bing published the illustrated book Women from Cradle to Old Age – 1929-1955, which contains numerous monochrome as well as color photographic portraits of women. The foreword was written by Gisèle Freund.

The emerging attention that Bing has enjoyed from the 1970s through the 1980s can be traced back to the growing fascination and interest in European photography of the 1920s and 1930s.[19]

From 1984 onwards, Ilse Bing made a number of appearances in the USA and Germany as a speaker on the development of modern art, especially photography. In the course of this activity she held i.a. Lectures in Frankfurt, Essen, Cologne, New Orleans and New York.[20]

In the last few decades of her life, she wrote poetry, made drawings and collages, and occasionally incorporated bits of photos. She was interested in combining mathematics, words, and images.[4]

Bing died on March 10, 1998, shortly before her ninety-ninth birthday, in New York.

Artistic practice and subjects

editArtistic practice

editIlse Bing always took photos from a very individual point of view, both for portraits and for countless architectural photos. What they work best characterizes enlargement of fragments of 35mm film her Leica and the resulting idiosyncratic cropping.[19] Although Bing experimented a lot, her photographs often seem characterized by a natural perfection. While the photographer's access to her craft was often spontaneous and intuitive, it was also characterized by great care and precision.[21] Her work was shaped by contemporary abstract and non-representational painting as well as by New Vision and Surrealism.[19] Since working in the darkroom had a significant impact on the results and appearance of Bing's photography, she always developed her negatives herself.[22] She also discovered a type of solarisation for negatives independently of a similar process developed by the artist Man Ray.[4]

Subjects

editIn addition to numerous portraits, Ilse Bing was primarily interested in urban motifs. They were fascinated by architectural elements and structures as well as urban hustle and bustle. Her way of working repeatedly explores the tracing of symmetry and rhythm in the experience of everyday situations. Bing always worked without additional lighting and operated exclusively with the existing lighting conditions. She used both artificial light sources such as illuminated windows, lanterns, street lamps, spotlights or the Eiffel Tower, as well as natural light from the sun and moon. Reflections can often be found in her work, e.g. in rain puddles, rivers and seas. Bing developed a feeling for movement and standstill, which she expressed in the photographs of water as well as of people and objects.

Words as Visions and Numbers in Images

editWords as Visions: Logograms (1974)

editIn the book dedicated to Konrad Wolff, Ilse Bing presents 111 associated words, which are listed in three languages (German, English and French) and illustrated by her own drawings:

“to be, to have, words, yes, no, why, because, good, bad, crime, pain, envy, mine, i, you, they, identity, reality, illusion, hope, expectation, inspiration, awe, hate, love, ideal, sleep, death, mourning, (to) remember, forgotten, lost, missing, alone, lonely, bored, alive, happy, (to) smile, when, time, timeless, now, yesterday, tomorrow, ever, never, final, endless, no more, eternity, where, here, nowhere, probable, perhaps, sure, obvious, enough, absolute, old, new, discovery, invention, noise, silence, sound, ugly, beautiful, warm, hot, cold, slow, fast, ready, alert, very, and, by, if, so, but, please, thanks, (to) begin, (to) wait, good-bye, something, everything, nothing, this, demonic, true, lie, error, mistake, doubt, trusting, success, bravo, must, chance, hazard, happening, epilogue“[23]

Bing explains the choice of words in the book's epilogue:

“– i picked the words like flowers in a field. the ones which signalled me the strongest were taken first. there is no apparent systems in the choice or order of words, and yet they may stand for, and unveil, the hidden body of my thoughts –”[23]

Numbers in Images: Illuminations of Numerical Meanings (1976)

editIn this work, published in 1976, Ilse Bing dedicates herself to numbers and thus returns to a certain extent to the origins of her academic training when she was still studying mathematics and physics. As in the previously published Words as Visions, the book is fully illustrated with Bing's drawings.

She introduces her thoughts and poems about numbers as follows:

„this limited selection does not touch on all facets of numbers, because its function is to illuminate, and not to explain. it deals with the very lowest numbers, those which we still can count on our fingers. for these are the base of the entire numerical row, and also the fundament for all mathematical constructions.“[24]

Awards

edit- 1990: Women’s Caucus for Art Award, New York.

- 1993: First Gold Medal Award for Photography vom National Arts Club, New York.

Exhibitions

edit- 1948: „Ilse Bing Photographs”, The Brookly Museum

- 1985: „Ilse Bing: Three Decades of Photography“, New Orleans Museum of Art

- 1986: „Ilse Bing“, International Center of Photography, New York

- 1995: „Ilse Bing – Marta Hoepffner – Abisag Tüllmann. Drei Fotografinnen in Frankfurt“, Historical Museum, Frankfurt

- 1996: „Ilse Bing – Fotografien 1929–1956“, Suermondt-Ludwig-Museum, Aachen

- 2004: „Ilse Bing: Queen of the Leica“, Victoria & Albert Museum, London

- 2019: “Ilse Bing (1899-1998): Fotografien”, Galerie Berinson, Berlin

- 2020: “Ilse Bing: Paris and Beyond”, F11 Foto Museum, Hong Kong

- 2020: “Ilse Bing: Queen of the Leica”, The Cleveland Museum of Art

- 2021: in "The New Woman Behind the Camera", The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York [25]

Documentary

editBing was one of three female photographers portrayed in Drei Fotografinnen: Ilse Bing, Grete Stern, Ellen Auerbach, a 1993 documentary by Berlin filmmaker Antonia Lerch.[26]

Public collections

edit- Art Institute of Chicago[27]

- New Orleans Museum of Art[27]

- Glyndebourne[27]

- Jewish Museum, Berlin[27]

- Jewish Museum (Manhattan)[27]

- Los Angeles County Museum of Art[27]

- MOCA Grand Avenue[27]

- Museum Folkwang[27]

- Museum of Modern Art (MoMA)[27]

- National Gallery of Canada[27]

- Rijksmuseum Amsterdam[28]

- San Francisco Museum of Modern Art[27]

- Victoria & Albert Museum[27]

References

edit- ^ a b c d Victoria and Albert Museum, Online Museum, Web Team. "Ilse Bing Biography". www.vam.ac.uk. Retrieved 2018-03-09.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "The Cleveland Museum of Art". 11 December 2019.

- ^ a b c Schmalbach, Hilary (1996). Ilse Bing: Fotografien 1929-1956. Aachen. p. 107. ISBN 3-929203-12-X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c d Loke, Margarett (1998-03-15). "Ilse Bing, 98, 1930's Pioneer Of Avant-Garde Photography". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2018-03-09.

- ^ a b c d arts, Roberta Hershenson; Roberta Hershenson writes frequently about the (1986-02-23). "Camera Pioneer Aluted at Icp". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2018-03-04.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Barrett, Nancy C. (1985). Ilse Bing: Three Decades of Photography. p. 21. ISBN 0-89494-022-8.

- ^ Hörner, Unda (2002). Madame Man Ray: Fotografinnen der Avantgarde in Paris. Berlin. p. 102. ISBN 3-934703-36-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Dryansky, Larisa (2006). Ilse Bing: Photography through the looking glass. New York. p. 52. ISBN 0-8109-5546-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Koelbl, Herlinde (1989). Jüdische Porträts: Photographien und Interviews. Frankfurt am Main. p. 26. ISBN 3-10-040204-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Barrett, Nancy C. (1985). Ilse Bing: Three Decades of Photography. pp. 20f. ISBN 0-89494-022-8.

- ^ Dryansky, Larisa (2006). Ilse Bing: Photography through the looking glass. New York. p. 54. ISBN 0-8109-5546-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Ilse Bing | German-born photographer". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2018-03-09.

- ^ Dryansky, Larisa (2006). Ilse Bing: Photography through the looking glass. New York. pp. 54f. ISBN 0-8109-5546-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b "Ilse Bing | Jewish Women's Archive". jwa.org. Retrieved 2018-03-09.

- ^ Dryansky, Larisa (2006). Ilse Bing: Photography through the looking glass. New York. p. 55. ISBN 0-8109-5546-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Dryansky, Larisa (2006). Ilse Bing: Photography through the looking glass. New York. pp. 57f. ISBN 0-8109-5546-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Koelbl, Herlinde (1989). Jüdische Porträts: Photographien und Interviews. Frankfurt am Main. p. 28. ISBN 3-10-040204-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Schmalbach, Hilary (1996). Ilse Bing. Fotografien 1929-1956. Aachen. p. 109. ISBN 3-929203-12-X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c Barrett, Nancy C. (1985). Ilse Bing: Three Decades of Photography. p. 9. ISBN 0-89494-022-8.

- ^ Schmalbach, Hilary (1996). Ilse Bing. Fotografien 1929-1956. Aachen. p. 108. ISBN 3-929203-12-X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Barrett, Nancy C. (1985). Ilse Bing: Three Decades of Photography. p. 10. ISBN 0-89494-022-8.

- ^ Barrett, Nancy C. (1985). Ilse Bing: Three Decades of Photography. p. 24. ISBN 0-89494-022-8.

- ^ a b Bing, Ilse (1974). Words as Visions: Logograms. New York.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Bing, Ilse (1976). Numbers in Images: Illuminations of Numerical Meaning.

- ^ Pound, Cath. "How the 'New Woman' blazed a trail of empowerment". www.bbc.com. BBC. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- ^ "Film | Drei Fotografinnen: Ilse Bing, Grete Stern, Ellen Auerbach | absolut MEDIEN". absolutmedien.de (in German). Retrieved 2018-03-04.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l London, ArtFacts.Net Ltd. "Ilse Bing - Biography". www.artfacts.net. Archived from the original on 2006-07-21. Retrieved 2018-03-09.

- ^ Collection Rijksmuseum

Further reading

edit- Barrett, Nancy (1985). Ilse Bing, three decades of photography. New Orleans: New Orleans Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0894940224. OCLC 469479874.

- Dryansky, Larisa (2006). Ilse Bing: photography through the looking glass. New York: H.N. Abrams. ISBN 978-0810955462. OCLC 608305260.

- Reynaud, François (1987). Ilse Bing : Paris 1931-1952. Paris, France: Musée Carnavalet. OCLC 680579906.

- Schmalbach, Hilary (1996). Ilse Bing: Fotografien 1929-1956. Aachen, Germany: Suermondt-Ludwig-Museum Aachen. ISBN 978-3929203127. OCLC 432873363.

- Misselbeck, Reinhold, ed. (1996). 20th Century Photography. Germany: Museum Ludwig Cologne. Taschen. ISBN 978-3822858677. OCLC 680579906.

- Greenspoon, Leonard J. (2013). Fashioning Jews: Clothing, Culture, and Commerce. West Lafayette, Ind.: Purdue University Press. ISBN 9781557536570. OCLC 1058492422.

- Wilson, Dawn (Winter 2012). "Facing the Camera: Self-portraits of Photographers as Artists". The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism. 70 (1): 56–66. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6245.2011.01498.x. JSTOR 42635856.

- David, Travis (1987). "In and of the Eiffel Tower". Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies. 13 (1): 5–23. doi:10.2307/4115922. JSTOR 4115922.

- Sarah, Kennel (Autumn 2005). "Fantasies of the Street: Emigré Photography in Interwar Paris". History of Photography. 29 (3): 287–300. doi:10.1080/03087298.2005.10442803. JSTOR 4115922. S2CID 191967058.

External links

edit- Selection of photographs and information

- Ilse Bing fonds at the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario

- Lerch, Antonia. Drei Fotografinnen: Ilse Bing, Grete Stern, Ellen Auerbach. 1993