Magic, which encompasses the subgenres of illusion, stage magic, and close-up magic, among others, is a performing art in which audiences are entertained by tricks, effects, or illusions of seemingly impossible feats, using natural means.[1][2] It is to be distinguished from paranormal magic which are effects claimed to be created through supernatural means. It is one of the oldest performing arts in the world.

| Magic | |

|---|---|

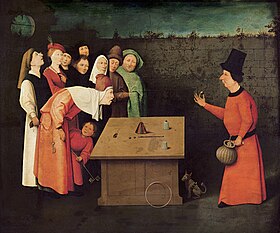

The Conjurer, 1475–1480, by Hieronymus Bosch or his workshop. Notice how the man in the back row steals another man's purse while applying misdirection by looking at the sky. |

Modern entertainment magic, as pioneered by 19th-century magician Jean-Eugène Robert-Houdin, has become a popular theatrical art form.[3] In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, magicians such as John Nevil Maskelyne and David Devant, Howard Thurston, Harry Kellar, and Harry Houdini achieved widespread commercial success during what has become known as "the Golden Age of Magic", a period in which performance magic became a staple of Broadway theatre, vaudeville, and music halls.[4] Meanwhile, magicians such as Georges Méliès, Gaston Velle, Walter R. Booth, and Orson Welles introduced pioneering filmmaking techniques informed by their knowledge of magic.[5][6][7]

Magic has retained its popularity into the 21st century by adapting to the mediums of television and the internet, with magicians such as David Copperfield, Penn & Teller, Paul Daniels, Criss Angel, David Blaine, Derren Brown, Mat Franco, and Shin Lim modernizing the art form.[8] Through the use of social media, magicians can now reach a wider audience than ever before.

Magicians are known for closely guarding the methods they use to achieve their effects, although they often share their techniques through both formal and informal training within the magic community.[9] Magicians use a variety of techniques, including sleight of hand, misdirection, optical and auditory illusions, hidden compartments, contortionism and specially constructed props, as well as verbal and nonverbal psychological techniques such as suggestion, hypnosis, and priming.[10]

History

editThe term "magic" etymologically derives from the Greek word mageia (μαγεία). In ancient times, Greeks and Persians had been at war for centuries, and the Persian priests, called magosh in Persian, came to be known as magoi in Greek. Ritual acts of Persian priests came to be known as mageia, and then magika—which eventually came to mean any foreign, unorthodox, or illegitimate ritual practice. To the general public, successful acts of illusion could be perceived as if it were similar to a feat of magic supposed to have been able to be performed by the ancient magoi. The performance of tricks of illusion, or magical illusion, and the apparent workings and effects of such acts have often been referred to as "magic" and particularly as magic tricks.

One of the earliest known books to explain magic secrets, The Discoverie of Witchcraft, was published in 1584. It was created by Reginald Scot to stop people from being killed for witchcraft. During the 17th century, many books were published that described magic tricks. Until the 18th century, magic shows were a common source of entertainment at fairs. The "Father" of modern entertainment magic was Jean Eugène Robert-Houdin, who had a magic theatre in Paris in 1845.[11] John Henry Anderson was pioneering the same transition in London in the 1840s. Towards the end of the 19th century, large magic shows permanently staged at big theatre venues became the norm.[12] As a form of entertainment, magic easily moved from theatrical venues to television magic specials.

Performances that modern observers would recognize as conjuring have been practiced throughout history. For example, a trick with three cups and balls has been performed since 3 BC[13] and is still performed today on stage and in street magic shows. For many recorded centuries, magicians were associated with the devil and the occult. During the 19th and 20th centuries, many stage magicians even capitalized on this notion in their advertisements.[14] The same level of ingenuity that was used to produce famous ancient deceptions such as the Trojan Horse would also have been used for entertainment, or at least for cheating in money games. They were also used by the practitioners of various religions and cults from ancient times onwards to frighten uneducated people into obedience or turn them into adherents. However, the profession of the illusionist gained strength only in the 18th century, and has enjoyed several popular vogues since.[citation needed]

Magic tricks

editOpinions vary among magicians on how to categorize a given effect, but a number of categories have been developed. Magicians may pull a rabbit from an empty hat, make something seem to disappear, or transform a red silk handkerchief into a green silk handkerchief. Magicians may also destroy something, like cutting a head off, and then "restore" it, make something appear to move from one place to another, or they may escape from a restraining device. Other illusions include making something appear to defy gravity, making a solid object appear to pass through another object, or appearing to predict the choice of a spectator. Many magic routines use combinations of effects.

Among the earliest books on the subject is Gantziony's work of 1489, Natural and Unnatural Magic, which describes and explains old-time tricks.[15] In 1584, Englishman Reginald Scot published The Discoverie of Witchcraft, part of which was devoted to debunking the claims that magicians used supernatural methods, and showing how their "magic tricks" were in reality accomplished. Among the tricks discussed were sleight-of-hand manipulations with rope, paper and coins. At the time, fear and belief in witchcraft was widespread and the book tried to demonstrate that these fears were misplaced.[16] Popular belief held that all obtainable copies were burned on the accession of James I in 1603.[17]

During the 17th century, many similar books were published that described in detail the methods of a number of magic tricks, including The Art of Conjuring (1614) and The Anatomy of Legerdemain: The Art of Juggling (c. 1675).

Until the 18th century, magic shows were a common source of entertainment at fairs, where itinerant performers would entertain the public with magic tricks, as well as the more traditional spectacles of sword swallowing, juggling and fire breathing. In the early 18th century, as belief in witchcraft was waning, the art became increasingly respectable and shows would be put on for rich private patrons. A notable figure in this transition was the English showman, Isaac Fawkes, who began to promote his act in advertisements from the 1720s—he even claimed to have performed for King George II. One of Fawkes' advertisements described his routine in some detail:

He takes an empty bag, lays it on the Table and turns it several times inside out, then commands 100 Eggs out of it and several showers of real Gold and silver, then the Bag beginning to swell several sorts of wild fowl run out of it upon the Table. He throws up a Pack of Cards, and causes them to be living birds flying about the room. He causes living Beasts, Birds, and other Creatures to appear upon the Table. He blows the spots of the Cards off and on, and changes them to any pictures.[18]

From 1756 to 1781, Jacob Philadelphia performed feats of magic, sometimes under the guise of scientific exhibitions, throughout Europe and in Russia.

Modern stage magic

editThe "Father" of modern entertainment magic was Jean Eugène Robert-Houdin, originally a clockmaker, who opened a magic theatre in Paris in 1845.[11] He transformed his art from one performed at fairs to a performance that the public paid to see at the theatre. His speciality was constructing mechanical automata that appeared to move and act as if alive. Many of Robert-Houdin's mechanisms for illusion were pirated by his assistant and ended up in the performances of his rivals, John Henry Anderson and Alexander Herrmann.

John Henry Anderson was pioneering the same transition in London. In 1840 he opened the New Strand Theatre, where he performed as The Great Wizard of the North. His success came from advertising his shows and captivating his audience with expert showmanship. He became one of the earliest magicians to attain a high level of world renown. He opened a second theatre in Glasgow in 1845.

Towards the end of the century, large magic shows permanently staged at big theatre venues became the norm.[12] The British performer J N Maskelyne and his partner Cooke were established at the Egyptian Hall in London's Piccadilly in 1873 by their manager William Morton, and continued there for 31 years. The show incorporated stage illusions and reinvented traditional tricks with exotic (often Oriental) imagery. The potential of the stage was exploited for hidden mechanisms and assistants, and the control it offers over the audience's point of view. Maskelyne and Cooke invented many of the illusions still performed today—one of his best-known being levitation.[19]

The model for the look of a "typical" magician—a man with wavy hair, a top hat, a goatee, and a tailcoat—was Alexander Herrmann (1844–1896), also known as Herrmann the Great. Herrmann was a French magician and was part of the Herrmann family name that is the "first-family of magic".

The escapologist and magician Harry Houdini (1874–1926) took his stage name from Robert-Houdin and developed a range of stage magic tricks, many of them based on what became known after his death as escapology. Houdini was genuinely skilled in techniques such as lockpicking and escaping straitjackets, but also made full use of the range of conjuring techniques, including fake equipment and collusion with individuals in the audience. Houdini's show-business savvy was as great as his performance skill. There is a Houdini Museum dedicated to him in Scranton, Pennsylvania.

The Magic Circle was formed in London in 1905 to promote and advance the art of stage magic.[20]

As a form of entertainment, magic easily moved from theatrical venues to television specials, which opened up new opportunities for deceptions, and brought stage magic to huge audiences. Famous magicians of the 20th century included Okito, David Devant, Harry Blackstone Sr., Harry Blackstone Jr., Howard Thurston, Theodore Annemann, Cardini, Joseph Dunninger, Dai Vernon, Fred Culpitt, Tommy Wonder, Siegfried & Roy, and Doug Henning. Popular 20th- and 21st-century magicians include David Copperfield, Lance Burton, James Randi, Penn and Teller, David Blaine, Criss Angel, Derren Brown, Dynamo, Shin Lim, Jay & Joss and Hans Klok. Well-known women magicians include Dell O'Dell and Dorothy Dietrich. Most television magicians perform before a live audience, who provide the remote viewer with a reassurance that the illusions are not obtained with post-production visual effects.

Many of the principles of stage magic are old. There is an expression, "it's all done with smoke and mirrors", used to explain something baffling, but effects seldom use mirrors today, due to the amount of installation work and transport difficulties. For example, the famous Pepper's Ghost, a stage illusion first used in 19th-century London, required a specially built theatre. Modern performers have vanished objects as large as the Taj Mahal, the Statue of Liberty, and a space shuttle, using other kinds of optical deceptions.

Types of magic performance

editMagic is often described according to various specialties or genres.

Stage illusions

editStage illusions are performed for large audiences, typically within a theatre or auditorium. This type of magic is distinguished by large-scale props, the use of assistants and often exotic animals such as elephants and tigers. Famous stage illusionists, past and present, include Harry Blackstone, Sr., Howard Thurston, Chung Ling Soo, David Copperfield, Lance Burton, Silvan, Siegfried & Roy, and Harry Blackstone, Jr.

Parlor magic

editParlor magic is done for larger audiences than close-up magic (which is for a few people or even one person) and for smaller audiences than stage magic. In parlor magic, the performer is usually standing and on the same level as the audience, which may be seated on chairs or even on the floor. According to the Encyclopedia of Magic and Magicians by T.A. Waters, "The phrase [parlor magic] is often used as a pejorative to imply that an effect under discussion is not suitable for professional performance." Also, many magicians consider the term "parlor" old fashioned and limiting, since this type of magic is often done in rooms much larger than the traditional parlor, or even outdoors. A better term for this branch of magic may be "platform", "club" or "cabaret". Examples of such magicians include Jeff McBride, David Abbott, Channing Pollock, Black Herman, and Fred Kaps.

Close-up magic

editClose-up magic (or table magic) is performed with the audience close to the magician, sometimes even one-on-one. It usually makes use of everyday items as props, such as cards (see Card manipulation), coins (see Coin magic), and seemingly 'impromptu' effects. This may be called "table magic", particularly when performed as dinner entertainment. Ricky Jay, Mahdi Moudini, and Lee Asher, following in the traditions of Dai Vernon, Slydini, and Max Malini, are considered among the foremost practitioners of close-up magic.

Escapology

editEscapology is the branch of magic that deals with escapes from confinement or restraints. Harry Houdini is a well-known example of an escape artist or escapologist.

Pickpocket magic

editPickpocket magicians use magic to misdirect members of the audience while removing wallets, belts, ties, and other personal effects. It can be presented on a stage, in a cabaret setting, before small close-up groups, or even for one spectator. Well-known pickpockets include James Freedman, David Avadon, Bob Arno, and Apollo Robbins.

Mentalism

editMentalism creates the impression in the minds of the audience that the performer possesses special powers to read thoughts, predict events, control other minds, and similar feats. It can be presented on a stage, in a cabaret setting, before small close-up groups, or even for one spectator. Well-known mentalists of the past and present include Alexander, The Zancigs, Axel Hellstrom, Dunninger, Kreskin, Deddy Corbuzier, Derren Brown, Rich Ferguson, Guy Bavli, Banachek, Max Maven, and Alain Nu.

Séances

editTheatrical séances simulate spiritualistic or mediumistic phenomena for theatrical effect. This genre of stage magic has been misused at times by charlatans pretending to actually be in contact with spirits or supernatural forces. For this reason, some well-known magicians such as James Randi[21][22] (AKA "The Amazing Randi") have made it their goal to debunk such paranormal phenomena and illustrate that any such effects may be achieved by natural or human means. Randi was the "foremost skeptic" in this regard in the United States.[23]

Children's magic

editChildren's magic is performed for an audience primarily composed of children. It is typically performed at birthday parties, preschools, elementary schools, Sunday schools, or libraries. This type of magic is usually comedic in nature and involves audience interaction as well as volunteer assistants.

Online magic

editOnline magic tricks were designed to function on a computer screen. The computer screen affords ways to incorporate magic from the magician's wand to the computer mouse. The use of computing technologies in performance can be traced back to a 1984 presentation by David Copperfield, who used a Commodore 64 to create a "magic show" for his audience. More recently, virtual performers have been experimenting with captivating digital animations and illusions that blur the lines between magic tricks and reality. In some cases, the computer essentially replaces the online magician.

In a 2008 TED Talk, Penn Jillette discussed how technology will continue to play a role in magic by influencing media and communication. According to Jillette, magicians continue to innovate in not only digital communication but also live performances that utilize digital effects. The 2020 COVID-19 lockdowns ushered onto the world stage a surge of online magic shows. These shows are performed via video conferencing platforms such as Zoom.

Some online magic tricks recreate traditional card tricks and require user participation, while others, like Plato's Cursed Triangle, are based on mathematical, geometrical, and/or optical illusions. One such online magic trick, called Esmeralda's Crystal Ball,[24] became a viral phenomenon that fooled so many computer users into believing that their computer had supernatural powers, that the fact-checking website Snopes dedicated a page to debunking the trick.[25]

German magician Wittus Witt performed interactive magic tricks live on TV from 1993 to 1997. Viewers were able to call Wittus Witt live in the television studio and perform a magic trick with him directly. In total, Witt performed this special magic 87 times, every other week.[26]

Theatrical magic

editTheatrical magic describes a dramaturgically well thought-out performance that has been specially designed for the theater and theater-like situations. It is not about individual tricks that are strung together, but about logical connections of tricks that lead to a story. The protagonists of this magic stage art were the German magician Fredo Marvelli, Punx, and Alexander Adrion. In the United States, they included Richard Hatch and Max Maven.

Mathemagic

editMathemagic is a genre of stage magic that combines magic and mathematics. It is commonly used by children's magicians and mentalists.

Corporate magic

editCorporate magic or trade show magic uses magic as a communication and sales tool, as opposed to just straightforward entertainment. Corporate magicians may come from a business background and typically present at meetings, conferences and product launches. They run workshops and can sometimes be found at trade shows, where their patter and illusions enhance an entertaining presentation of the products offered by their corporate sponsors. Pioneer performers in this arena include Eddie Tullock[27] and Guy Bavli.[28][29]

Gospel magic

editGospel magic uses magic to catechize and evangelize. Gospel magic was first used by St. John Bosco to interest children in 19th-century Turin, Italy to come back to school, to accept assistance and to attend church. The Jewish equivalent is termed Torah magic.

Street magic

editStreet magic is a form of street performing or busking that employs a hybrid of stage magic, platform, and close-up magic, usually performed 'in the round' or surrounded by the audience. Notable modern street magic performers include Jeff Sheridan, Gazzo, and Wittus Witt. Since the first David Blaine TV special Street Magic aired in 1997, the term "street magic" has also come to describe a style of 'guerilla' performance in which magicians approach and perform for unsuspecting members of the public on the street. Unlike traditional street magic, this style is almost purely designed for TV and gains its impact from the wild reactions of the public. Magicians of this type include David Blaine and Cyril Takayama.

Bizarre magic

editBizarre magic is a branch of stage magic that creates eerie effects through its use of narratives and esoteric imagery.[30] The experience may be more akin to small, intimate theater or to a conventional magic show.[31] Bizarre magic often uses horror, supernatural, and science fiction imagery in addition to the standard commercial magic approaches of comedy and wonder.[32]

Shock magic

editShock magic is a genre of magic that shocks the audience. Sometimes referred to as "geek magic", it takes its roots from circus sideshows, in which 'freakish' performances were shown to audiences. Common shock magic or geek magic effects include eating razor blades, needle-through-arm, string through neck and pen-through-tongue.

Comedy magic

editComedy magic is the use of magic in which is combined with stand-up comedy. Famous comedy magicians include The Amazing Johnathan, Holly Balay, Mac King, and Penn & Teller.

Quick-change magic

editQuick-change magic is the use of magic which is combined with the very quick changing of costumes. Famous quick-change artists include Sos & Victoria Petrosyan.

Camera magic

editCamera magic (or "video magic") is magic that is aimed at viewers watching broadcasts or recordings. It includes tricks based on the restricted viewing angles of cameras and clever editing. Camera magic often features paid extras posing as spectators who may even be assisting in the performance. Camera magic can be done live, such as Derren Brown's lottery prediction. Famous examples of camera magic include David Copperfield's Floating Over the Grand Canyon and many of Criss Angel's illusions.

Classical magic

editClassical magic is a style of magic that conveys feelings of elegance and skill akin to prominent magicians of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Mechanical magic

editMechanical magic is a form of stage magic in which the magician uses a variety of mechanical devices to perform acts that appear to be physically impossible. Examples include such things as a false-bottomed mortar in which the magician places an audience member's watch only to later produce several feet away inside a wooden frame.[33] Mechanical magic requires a certain degree of sleight of hand and carefully functioning mechanisms and devices to be performed convincingly. This form of magic was popular around the turn of the 19th century—today, many of the original mechanisms used for this magic have become antique collector's pieces and may require significant and careful restoration to function.

Categories of effects

editMagicians describe the type of tricks they perform in various ways. Opinions vary as to how to categorize a given effect, and disagreement as to what categories actually exist. For instance, some magicians consider "penetrations" a separate category, while others consider penetrations a form of restoration or teleportation. Some magicians today, such as Guy Hollingworth[34] and Tom Stone[35] have begun to challenge the notion that all magic effects fit into a limited number of categories. Among magicians who believe in a limited number of categories (such as Dariel Fitzkee, Harlan Tarbell, S.H. Sharpe), there has been disagreement as to how many different types of effects there are. Some of these are listed below.

- Production: The magician produces something from nothing—a rabbit from an empty hat, a fan of cards from thin air, a shower of coins from an empty bucket, a dove from a pan, or the magician himself or herself, appearing in a puff of smoke on an empty stage—all of these effects are productions.

- Vanish: The magician makes something disappear—a coin, a cage of doves, milk from a newspaper, an assistant from a cabinet, or even the Statue of Liberty. A vanish, being the reverse of a production, may use a similar technique in reverse.

- Transformation: The magician transforms something from one state into another—a silk handkerchief changes color, a lady turns into a tiger, an indifferent card changes to the spectator's chosen card.

Transformation: Change of color - Restoration: The magician destroys an object—a rope is cut, a newspaper is torn, a woman is cut in half, a borrowed watch is smashed to pieces—then restores it to its original state.

- Transposition: A transposition involves two or more objects. The magician will cause these objects to change places, as many times as he pleases, and in some cases, ends with a kicker by transforming the objects into something else.

- Teleportation: The magician causes something to move from one place to another—a borrowed ring is found inside a ball of wool, a canary inside a light bulb, an assistant from a cabinet to the back of the theatre, or a coin from one hand to the other. When two objects exchange places, it is called a transposition: a simultaneous, double transportation. A transportation can be seen as a combination of a vanish and a production. When performed by a mentalist it might be called teleportation.

- Escape: The magician (or less often, an assistant) is placed in a restraining device (e.g., handcuffs or a straitjacket) or a death trap, and escapes to safety. Examples include being put in a straitjacket and into an overflowing tank of water, and being tied up and placed in a car being sent through a car crusher.

- Levitation: The magician defies gravity, either by making something float in the air, or with the aid of another object (suspension)—a silver ball floats around a cloth, an assistant floats in mid-air, another is suspended from a broom, a scarf dances in a sealed bottle, the magician levitates his own body in midair. There are many popular ways to create this illusion, including Asrah levitation, Balducci levitation, invisible thread, and King levitation.[citation needed] The flying illusion has often been performed by David Copperfield. Harry Blackstone floated a light bulb over the heads of the public.

- Penetration: The magician makes a solid object pass through another—a set of steel rings link and unlink, a candle penetrates an arm, swords pass through an assistant in a basket, a salt shaker penetrates a tabletop, or a man walks through a mirror. Sometimes referred to as "solid-through-solid".

- Prediction: The magician accurately predicts the choice of a spectator or the outcome of an event—a newspaper headline, the total amount of loose change in the spectator's pocket, a picture drawn on a slate—under seemingly impossible circumstances.

Many magic routines use combinations of effects. For example, in "cups and balls" a magician may use vanishes, productions, penetrations, teleportation and transformations as part of the one presentation.

The methodology behind magic is often referred to as a science (often a branch of physics) while the performance aspect is more of an art form.

Learning magic

editDedication to magic can teach confidence and creativity, as well as the work ethic associated with regular practice and the responsibility that comes with devotion to an art.[36] The teaching of performance magic was once a secretive practice.[37] Professional magicians were unwilling to share knowledge with anyone outside the profession to prevent the laity from learning their secrets.[38] This often made it difficult for an interested apprentice to learn anything but the basics of magic. Some had strict rules against members discussing magic secrets with anyone but established magicians.

From the 1584 publication of Reginald Scot's Discoverie of Witchcraft until the end of the 19th century, only a few books were available for magicians to learn the craft, whereas today mass-market books offer a myriad titles. Videos and DVDs are newer media, but many of the methods found in this format are readily found in previously published books. However, they can serve as a visual demonstration.

Persons interested in learning to perform magic can join magic clubs. Here magicians, both seasoned and novitiate, can work together and help one another for mutual improvement, to learn new techniques, to discuss all aspects of magic, to perform for each other—sharing advice, encouragement, and criticism. Before a magician can join one of these clubs, they usually have to audition. The purpose is to show to the membership they are a magician and not just someone off the street wanting to discover magic secrets.

The world's largest magic organization is the International Brotherhood of Magicians; it publishes a monthly journal, The Linking Ring. The oldest organization is the Society of American Magicians, which publishes the monthly magazine M-U-M and of which Houdini was a member and president for several years. In London, England, there is The Magic Circle, which houses the largest magic library in Europe. Also PSYCRETS—The British Society of Mystery Entertainers[39]—caters specifically to mentalists, bizarrists, storytellers, readers, spiritualist performers, and other mystery entertainers. Davenport's Magic[40] in London's The Strand was the world's oldest family-run magic shop.[41] It is now closed. The Magic Castle in Hollywood, California, is home to the Academy of Magical Arts.

Traditionally, magicians refuse to reveal the methods behind their tricks to the audience. Membership in professional magicians' organizations often requires a commitment never to reveal the secrets of magic to non-magicians. When Justin Flom in 2020 began disclosing how tricks worked in Facebook videos, other magicians publicly and privately criticized and ostracized him.[42]

Magic performances tend to fall into a few specialties or genres. Stage illusions use large-scale props and even large animals. Platform magic is performed for a medium to large audience. Close-up magic is performed with the audience close to the magician. Escapology involves escapes from confinement or restraints. Pickpocket magicians take audience members' wallets, wristwatches, belts, and ties. Mentalism creates the illusion that the magician can read minds. Comedy magic is the use of magic combined with stand-up comedy, an example being Penn & Teller. Some modern illusionists believe that it is unethical to give a performance that claims to be anything other than a clever and skillful deception. Others argue that they can claim that the effects are due to magic. These apparently irreconcilable differences of opinion have led to some conflicts among performers. Another issue is the use of deceptive practices for personal gain outside the venue of a magic performance. Examples include fraudulent mediums, con men and grifters who use deception for cheating at card games.

Misuse of the term "magic"

editSome modern illusionists believe that it is unethical to give a performance that claims to be anything other than a clever and skillful deception. Most of these performers therefore eschew the term "magician" (which they view as making a claim to supernatural power) in favor of "illusionist" and similar descriptions; for example, the performer Jamy Ian Swiss makes these points by billing himself as an "honest liar".[43] Alternatively, many performers say that magical acts, as a form of theatre, need no more of a disclaimer than any play or film; this policy was advocated by the magician and mentalist Joseph Dunninger, who stated "For those who believe, no explanation is necessary; for those who do not believe, no explanation will suffice."[44]

These apparently irreconcilable differences of opinion have led to some conflicts among performers. For example, more than thirty years after the illusionist Uri Geller made his first appearances on television in the 1970s to exhibit his self-proclaimed psychic ability to bend spoons, his actions still provoke controversy among some magic performers, because he claimed what he did was not an illusion. On the other hand, because Geller bent—and continues to bend—spoons within a performance context and has lectured at several magic conventions, the Dunninger quote may be said to apply.

In 2016, self-proclaimed psychic The Amazing Kreskin was barred from sending fraudulent letters to solicit money from the elderly. "This settlement ends these efforts to cheat Iowa's most vulnerable people," stated Attorney General Tom Miller. "The letters were shamelessly predatory and manipulative, variously promising riches, protection from ill-health, and even personal friendship to each recipient – all to get the victim to send money."[45]

Less fraught with controversy, however, may be the use of deceptive practices by those who employ stage magic techniques for personal gain outside the venue of a magic performance.

Fraudulent mediums have long capitalized on the popular belief in paranormal phenomena to prey on the bereaved for financial gain. From the 1840s to the 1920s, during the greatest popularity of the spiritualism religious movement as well as public interest in séances, a number of fraudulent mediums used stage magic methods to perform illusions such as table-knocking, slate-writing, and telekinetic effects, which they attributed to the actions of ghosts or other spirits. The great escapologist and illusionist Harry Houdini devoted much of his time to exposing such fraudulent operators.[46] Magician James Randi, magic duo Penn & Teller, and the mentalist Derren Brown have also devoted much time to investigating and debunking paranormal, occult, and supernatural claims.[47][48]

Fraudulent faith healers have also been shown to employ sleight of hand to give the appearance of removing chicken-giblet "tumors" from patients' abdomens.[49]

Con men and grifters too may use techniques of stage magic for fraudulent goals. Cheating at card games is an obvious example, and not a surprising one: one of the most respected textbooks of card techniques for magicians, The Expert at the Card Table by Erdnase, was primarily written as an instruction manual for card sharps. The card trick known as "Find the Lady" or "Three-card Monte" is an old favourite of street hustlers, who lure the victim into betting on what seems like a simple proposition: to identify, after a seemingly easy-to-track mixing sequence, which one of three face-down cards is the Queen. Another example is the shell game, in which a pea is hidden under one of three walnut shells, then shuffled around the table (or sidewalk) so slowly as to make the pea's position seemingly obvious. Although these are well known as frauds, people still lose money on them; a shell-game ring was broken up in Los Angeles as recently as December 2009.[50]

Researching magic

editBecause of the secretive nature of magic, research can be a challenge.[51] Many magic resources are privately held and most libraries only have small populist collections of magicana. However, organizations exist to band together independent collectors, writers, and researchers of magic history, including the Magic Collectors' Association,[52] which publishes a quarterly magazine and hosts an annual convention; and the Conjuring Arts Research Center,[53] which publishes a monthly newsletter and biannual magazine, and offers its members use of a searchable database of rare books and periodicals.

Performance magic is particularly notable as a key area of popular culture from the mid-19th to mid-20th centuries. Many performances and performers can be followed through newspapers[54] of the time.

Many books have been written about magic tricks; so many are written every year that at least one magic author[55] has suggested that more books are written about magic than any other performing art. Although the bulk of these books are not seen on the shelves of libraries or public bookstores, the serious student can find many titles through specialized stores catering to the needs of magic performers.

Several notable public research collections on magic are the WG Alma Conjuring Collection[56] at the State Library of Victoria; the R. B. Robbins Collection of Stage Magic and Conjuring[57] at the State Library of NSW; the H. Adrian Smith Collection of Conjuring and Magicana[58] at Brown University; and the Carl W. Jones Magic Collection, 1870s–1948[59] at Princeton University.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Foley, Elise (3 May 2016). "Do You Believe In Magic? Congress Does" Archived 2016-06-15 at the Wayback Machine. The Huffington Post. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- ^ Gibson, Bill (18 March 2016). "David Copperfield Is The Magic Force Behind A Must-Read Congressional Resolution" Archived 2016-05-27 at the Wayback Machine. The Washington Post. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- ^ Recognizing magic as a rare and valuable art form and national treasure (H.Res 642). March 2016.

- ^ Steinmeyer, Jim (2003). Hiding the Elephant. Da Capo Press.

- ^ King, Susan (19 Nov 2013). "A look at the magicians of cinema" The Los Angeles Times

- ^ Gress, Jon (2015). Visual Effects and Compositing. San Francisco: New Riders. p. 23. ISBN 9780133807240. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- ^ Buffum, Richard (20 October 1985). "Magic Loomed Large in World of Orson Welles" The Los Angeles Times

- ^ Chambers, Colin (2002). Continuum Companion to Twentieth Century Theatre. Continuum. p. 471.

- ^ Rissanen, Olli; Pitkänen, Petteri; Juvonen, Antti; Kuhn, Gustav; Hakkarainen, Kai (2014). "Expertise among professional magicians: an interview study". Frontiers in Psychology. 5. Finland: 1484. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01484. PMC 4274899. PMID 25566156.

- ^ Pailhès, Alice; Gustav, Kuhn (2020). "Influencing choices with conversational primes: How a magic trick unconsciously influences card choices". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 117 (30): 17675–17679. Bibcode:2020PNAS..11717675P. doi:10.1073/pnas.2000682117. PMC 7395500. PMID 32661142.

- ^ a b Jones, Graham M. (2008). "The Family Romance of Modern Magic: Contesting Robert-Houdin's Cultural Legacy in Contemporary France". Performing Magic on the Western Stage. pp. 33–60. doi:10.1057/9780230617124_3. ISBN 978-1349374649. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ a b "History of Magic". This French site, Magiczoom, has now closed its doors. Archived from the original on 15 May 2006.

- ^ Macknik, Stephen L. "Penn & Teller's Cups-and-Balls Magic Trick". Scientific American Blog Network. Archived from the original on 6 July 2020. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- ^ Romano, Chuck (January 1995). "The Art of Deception, or The Magical Affinity Between Conjuring and Art". The Linking Ring. 75 (1): 67–70.

- ^ Houdini, Harry (1908). The Unmasking of Robert-Houdin. p. 19.

- ^ "10 Facts About Magicians – Andi Gladwin – Close-Up Magician". Illusionist.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2 October 2010. Retrieved 2 January 2011.

- ^ Almond, Philip C. (2009). "King James I and the burning of Reginald Scot's The Discoverie of Witchcraft: The invention of a tradition". Notes and Queries. 56 (2): 209–213. doi:10.1093/notesj/gjp002.

- ^ Christopher, Milbourne (1991) [1962]. Magic: A Picture History. New York: Courier Dover Publications. p. 16. ISBN 0486263738.

- ^ Dawes, Edwin (1979). The Great Illusionists. Chartwell Books Inc. p. 161. ISBN 978-0890092408.

- ^ Jack Delvin. "About The Magic Circle". Archived from the original on 11 December 2013. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ^ "James Randi". www.macfound.org. Archived from the original on 15 January 2021. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- ^ Fox, Margalit (22 October 2020). "James Randi, Magician Who Debunked Paranormal Claims, Dies at 92". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 22 October 2020. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- ^ "Final goodbye: Recalling influential people who died in 2020". www.wwnytv.com. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 12 January 2021. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- ^ "online magic tricks magical illusions". Real Magic. Archived from the original on 17 April 2011. Retrieved 17 March 2012.

- ^ "Online Psychic Trick". snopes.com. 21 February 2003. Retrieved 17 March 2012.

- ^ Halbe Wahrheit – Ganzes Vergnügen, book by Franz Schiffer,Eppe Co., ISBN 978-3-89089-861-2, 2008, page 125

- ^ Bill Herz with Paul Harris. Secrets of the Astonishing Executive (New York: Avon Books, 1991). [ISBN missing]

- ^ "Guy Bavli – Biography". All About Magicians.com. Archived from the original on 3 January 2011. Retrieved 2 January 2011.

- ^ Master of the Mind – Guy Bavoi

- ^ Jones, Graham (2011). Trade of the Tricks: Inside the Magician's Craft. University of California Press. p. 125. ISBN 978-0520950528.

- ^ Burger, Eugene (1989). "A Midnight Talk". The New Invocation (49): 558–593.

- ^ Taylor, Nik; Nolan, Stuart. "Performing Fabulous Monsters: re-inventing the gothic personae in bizarre magick". Monstrous media/spectral subjects : imaging Gothic from the nineteenth century to the present. Botting, Fred,, Spooner, Catherine. Manchester. pp. 128–142. ISBN 978-0719098130. OCLC 921217998.

- ^ Nevil Monroe Hopkins (1898). Twentieth Century Magic and the Construction of Modern Magical Apparatus. Routledge & Sons Ltd. pp. 29–70. Archived from the original on 8 April 2023. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

- ^ Hollingworth, Guy. "Waiting For Inspiration." Genii Magazine. January 2008 – December 2008.

- ^ Stone, Tom. "Lodestones." Genii Magazine. February 2009

- ^ Hass, Larry & Burger, Eugene (November 2000). "The Theory and Art of Magic". The Linking Ring. The International Brotherhood of Magicians.

- ^ "Magic Summer Reading List". www.mattmatthewsmagic.com. Archived from the original on 1 March 2021. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- ^ "The Magician's Oath: A Conversation with Pat Hammond on Magic, Science, and the Wind | Drachen Foundation". www.drachen.org. Archived from the original on 1 December 2016. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- ^ S.J.Drury [web-aviso.com]. "psycrets.org.uk". psycrets.org.uk. Archived from the original on 31 July 2019. Retrieved 17 March 2012.

- ^ "Davenports Magic. Central London magic shop and school since 1898". www.davenportsmagic.co.uk. Archived from the original on 22 October 2018. Retrieved 18 December 2018.

- ^ "Oldest magic shop". Guinness World Records. Archived from the original on 1 January 2019. Retrieved 18 December 2018.

- ^ Mears, Ashley (28 July 2022). "Hocus focus: how magicians made a fortune on Facebook". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 6 August 2022.

- ^ Norman, Tony (31 October 2008). "Deception's his tool (but he's no politician)". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Archived from the original on 9 March 2014. Retrieved 9 March 2014.

- ^ "Memorable-Quotes.com". Memorable-Quotes.com. Archived from the original on 7 February 2011. Retrieved 2 January 2011.

- ^ "Judgment Bars New York-based Mailing Operation from Iowa; Miller Alleged Company Defrauded Elderly". Iowa Attorney General. Archived from the original on 1 September 2021. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

- ^ Harry Houdini. A Magician Among the Spirits (New York: Harper and Bros., 1924)

- ^ Randi, James (9 February 2007). "More Geller Woo-Woo". SWIFT Newsletter. James Randi Educational Foundation. Archived from the original on 10 July 2009. Retrieved 29 January 2007.

- ^ One-Million-Dollar Challenge Archived 2011-07-27 at the Wayback Machine from MIT Media Lab: Affective Computing Group

- ^ Robert T. Carroll (23 February 2009). "Psychic 'surgery'". The Skeptic's Dictionary. Archived from the original on 14 May 2011. Retrieved 19 August 2010.

- ^ Andrew Blankenstein. "8 Arrested in Downtown Shell-Game Operation," Los Angeles Times, December 10, 2009.

- ^ Dunstan, Dominique. "Research Guides: Magic & magicians: Get started". guides.slv.vic.gov.au. Archived from the original on 18 December 2018. Retrieved 18 December 2018.

- ^ "Magic Collectors". Magicana. Archived from the original on 21 October 2013. Retrieved 17 March 2012.

- ^ "conjuringarts.org". conjuringarts.org. Archived from the original on 29 June 2005. Retrieved 17 March 2012.

- ^ "Magicians – Magic & magicians – Research Guides at State Library of Victoria". Guides.slv.vic.gov.au. 12 February 2012. Archived from the original on 26 March 2015. Retrieved 17 March 2012.

- ^ Bart King, The Pocket Guide to Magic, Gibbs Smith, 2009

- ^ "Get started – Magic & magicians – Research Guides at State Library of Victoria". Guides.slv.vic.gov.au. 12 February 2012. Archived from the original on 6 April 2011. Retrieved 17 March 2012.

- ^ "Special collections | State Library of New South Wales". Sl.nsw.gov.au. 3 February 2010. Archived from the original on 22 April 2011. Retrieved 17 March 2012.

- ^ "John Hay Library: Collections". Brown.edu. Archived from the original on 30 December 2011. Retrieved 17 March 2012.

- ^ "Carl W. Jones Magic Collection, 1870s–1948: Finding Aid". Arks.princeton.edu. Retrieved 17 March 2012.

Further reading

edit- Barrett, Caitlín E. "Plaster Perspectives on "Magical" Gems: Rethinking the Meaning of "Magic"". Cornell Collection of Antiquities. Cornell University Library. Archived from the original on 26 May 2015. Retrieved 24 August 2015.

- Burlingame, H. J. (1895). History of Magic and Magicians. Charles L. Burlingame & Company.

- Christopher, Maurine; Christopher, Milbourne (1996). The Illustrated History of Magic. Heinemann. ISBN 0435070169.

- Christopher, Milbourne (1962). Panorama of Magic.

- Daniel, Noel; Caveney, Mike; Steinmeyer, Jim, eds. (2009). Magic 1400–1950s. Los Angeles: Taschen. ISBN 978-3836509770.

- Dunninger, Joseph. The Complete Encyclopedia of Magic.

- Nadis, Fred, ed. (2006). Wonder Shows: Performing Science, Magic, and Religion in America. Rutgers University Press.

- Frost, Thomas (1876). The Lives of the Conjurors. Tinsley Brothers.

- Hart, Martin T. (2014). We know how they did it!. Manipulatist Books Global.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - Price, David (1985). Magic: A Pictorial History of Conjurers in the Theatre. Cornwall Books.

- Randi, James (1992). Conjuring: A Definitive History. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0312086342.

- Stebbins, Robert A. (1993). Career, Culture and Social Psychology in a Variety Art: The Magician. Malabar, FL: Krieger.

- Hawk, Mike. The Illusionist. Tiverton, ON: IBM, 1999. 234–238. Print. (Hawk 234–238)[ISBN missing]

External links

edit- Boston Public Library. Magic posters

- State Library of Victoria (Australia). Magic and magicians Research Guide

- Science, Math and Magic Books From the Rare Book and Special Collections Division at the Library of Congress

- Magic Apparatus From the Rare Book and Special Collections Division at the Library of Congress