This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2011) |

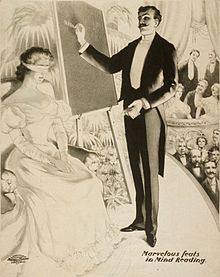

Mentalism is a performing art in which its practitioners, known as mentalists, appear to demonstrate highly developed mental or intuitive abilities. Mentalists perform a theatrical act that includes special effects that may appear to employ psychic or supernatural forces but that is actually achieved by "ordinary conjuring means",[1] natural human abilities (i.e. reading body language, refined intuition, subliminal communication, emotional intelligence), and an in-depth understanding of key principles from human psychology or other behavioral sciences.[2][3][4] Performances may appear to include hypnosis, telepathy, clairvoyance, divination, precognition, psychokinesis, mediumship, mind control, memory feats, deduction, and rapid mathematics.

Mentalism is commonly classified as a subcategory of magic and, when performed by a stage magician, may also be referred to as mental magic. However, many professional mentalists today may generally distinguish themselves from magicians, insisting that their art form leverages a distinct skillset.[5] Instead of doing "magic tricks", mentalists argue that they produce psychological experiences for the mind and imagination, and expand reality with explorations of psychology, suggestion, and influence.[6] Mentalists are also often considered psychic entertainers,[6][7][8] although that category also contains non-mentalist performers such as psychic readers and bizarrists.

Some well-known magicians, such as Penn & Teller, and James Randi, argue that a key differentiation between a mentalist and someone who purports to be an actual psychic is that the former is open about being a skilled artist or entertainer who accomplishes their feats through practice, study, and natural means, while the latter may claim to actually possess genuine supernatural, psychic, or extrasensory powers and, thus, operates unethically.[1][9][10]

Renowned mentalist Joseph Dunninger, who also worked to debunk fraudulent mediums,[11] captured this key sentiment when he explained his impressive abilities in the following way: "Any child of ten could do this – with forty years of experience."[5] Like any performing art, mentalism requires years of dedication, extensive study, practice, and skill to perform well.

Background

editMuch of what modern mentalists perform in their acts can be traced back directly to "tests" of supernatural power that were carried out by mediums, spiritualists, and psychics in the 19th century.[12] However, the history of mentalism goes back even further. Accounts of seers and oracles can be found in the Old Testament[13] of the Bible and in works about ancient Greece.[14] Paracelsus reiterated the theme, so reminiscent of the ancient Greeks, that three principias were incorporated into humanity: the spiritual, the physical, and mentalistic phenomena.[15] The mentalist act generally cited as one of the earliest on record in the modern era was performed by diplomat and pioneering sleight-of-hand magician Girolamo Scotto in 1572.[5] The performance of mentalism may utilize conjuring principles including sleights, feints, misdirection, and other skills of street or stage magic.[16] Nonetheless, modern mentalists also now increasingly incorporate insights from human psychology and behavioral sciences to produce unexplainable experiences and effects for their audiences. Changing with the times, some mentalists incorporate an iPhone into their routine.[17]

Techniques

editPrinciple: sleight of hand and other traditional magicians' techniques

editMentalists typically seek to explain their effects as manifestations of psychology, hypnosis, an ability to influence by subtle verbal cues, an acute sensitivity to body language, etc. These are all genuine phenomena, but they are not sufficiently reliable or impressive to form the basis of a mentalism performance. These are in fact fake explanations - part of the mentalist's misdirection - and the true method being employed is classic magicians' trickery.

Written "billet"

editA characteristic feature of "mind-reading" by a mentalist is that the spectator must write the thought down. Various justifications are given for this - in order to enable the spectator to focus on the thought, or in order to show it to other audience members etc. - but the real reason is to enable the mentalist then secretly to access the written-down information. There are various techniques which the mentalist can use. A classic method is the "centre tear". The spectator is asked to commit her thought to writing on a small piece of paper (referred to by mentalists as a "billet"). She is told to write the thought in the centre of the billet, and sometimes a circle or a line will be added by the mentalist onto the billet to make sure she writes in the middle. She is then instructed to fold the billet up so that the writing cannot be seen by the mentalist. The mentalist then takes the billet and tears it into small pieces, which he may then burn or throw away or return to the spectator's hand "for safe-keeping". Secretly, during the tearing process, the mentalist tears out and secretes the centre part of the billet which bears the written thought, and later finds an opportunity to read it covertly. Alternatively the mentalist may covertly peek at the written thought. There are a large number of detailed choreographies used by mentalists to achieve a peek. One popular version - known as the "acidus novus" peek - requires the spectator to write her thought on the bottom right-hand corner of the billet. Typically the mentalist will fill up the other 3 quadrants of the billet with writing so that only the bottom right-hand quadrant is left clear. Once the thought is written and the billet folded, the mentalist will hold the billet up to the light to demonstrate that no writing can be seen through the paper. In the course of this action he is able, unobserved by the audience, to slip his thumb between the folds of the billet and expose a view of the bottom right-hand quadrant. He then gestures with the billet, bringing it at eye-level across his field of vision, and in so-doing is able secretly to peek at the spectator's written thought. This is only one of a number of such peek choreographies. Some involve placing the billet in a gimmicked wallet, which allows the mentalist covertly to see the writing. Others employ sleights of hand derived from card or coin magic.

Modern gimmicks

editIn addition to these traditional magicians' techniques, there is today a huge range of electronic, computer and other gimmicks available to the mentalist. These include dice which secretly transmit the numbers thrown, decks of cards which secretly transmit the cards chosen, notepads which secretly transmit what has been written etc. Smartphones have added an additional range of possibilities. For example, the mentalist can use concealed NFC tags to covertly download onto a spectator’s phone a fake version of a popular website such as Google Images, which allows him to know an image which the spectator believes has been chosen secretly.

Nail writing and its technological equivalents

editWhere a mind-reading performance does not involve the spectator writing the secret thought down, generally the method employed is that the mentalist purports to predict the secret thought by (apparently) writing an unseen prediction, often behind a clipboard or other hard surface, then he asks the spectator to reveal the thought, and the mentalist at that point quickly and covertly writes or completes his prediction using a nail writer or swami gimmick. These are small devices which allow the mentalist to write unseen with his thumb under cover of a clipboard or in his pocket.

Again, these traditional magicians’ devices have now been supplemented by technology. The mentalist can now buy blackboards and whiteboards which are capable of writing (apparently) handwritten messages fed to them remotely, small printers which can print a spectator’s chosen number and feed the printed paper into an (apparently) sealed jar, and a host of other technological gadgets which make it appear that the mentalist predicted the spectator’s thought, when in fact he simply waited for it to be disclosed by the spectator and then created the evidence of his “prediction”.

Pre-show work

editMany mentalism effects rely on pre-show work. This involves the mentalist or his assistant interacting with certain members of the audience before the performance begins. This can be in a pre-show reception, or in the auditorium itself as the audience take their seats, or even in the queue outside the performance venue before the performance. Pre-show work can take a number of forms. One type involves the mentalist talking to a spectator whom he will later, during his performance, involve in one of his effects. In this case the mentalist sets up the trick by covertly obtaining information from the spectator which he will later reveal during the performance. The interaction with the spectator may be made to seem like a casual “meet the audience” conversation, with no warning that the spectator is later to be involved in the performance. Alternatively, the mentalist may tell the spectator that he intends to involve her in his show. In that case the pre-show interaction is usually characterised as preparation “to save time during the show” or similar. Either way, the mentalist will use the occasion to obtain information from the spectator covertly for later revelation, either by traditional sleight of hand methods such as a billet peek, or by using electronic gimmickry such as a Parapad. Alternatively, the mentalist may ask the spectator to make a choice (eg a number, a playing card, a selection from a list of items) and to recall that choice when later asked to participate during the performance. Typically the spectator will believe she has a free choice, but in fact it will be a choice forced by the mentalist, This can be done in a number of ways. One popular method is a proprietary device called a Svenpad. This is a notepad in which every second page is imperceptibly shorter. The long pages each have written on them an item from a list of choices (eg film stars, holiday destinations etc), but the short pages each have the same item - the force choice - written on them. When riffled from front to back only the long pages are visible, showing the full range of different choices. But when riffled from back to front only the short pages are visible, each bearing the force selection. Other forcing methods include trick decks of cards, where all the cards are the same. During the performance itself, when the mentalist involves the spectator in his effect, he will usually aim by careful use of language to avoid any mention of the pre-show interaction to the wider audience, either by himself or the chosen spectator. His aim is to suggest that he and the spectator have not previously met. When the spectator’s covertly obtained information or forced choice is revealed, this greatly enhances the effect from the point of view of the wider audience. It will usually seem that the mentalist has elicited a wholly uncommunicated thought from a random audience member. The chosen spectator herself, having participated in the pre-show encounter, perceives a different and less spectacular effect. This is an example of dual reality (discussed below) in mentalism.[18]

Suggestion

editThis technique involves implanting an idea, thought, or impression in the mind of the spectator or participant. The mentalist does this by using subtle verbal cues, gestures, body language, and sometimes visual aids to influence their thoughts. For instance, asking someone to "think of any card in a normal deck" automatically plants the general idea of a playing card in their mind. Similarly, asking them to "visualize the card clearly in your mind" can put the image of a particular card in their imagination.[19]

Misdirection

editAlso known as diversion, this technique aims to divert the audience's attention away from the secret method or process behind a mentalism effect. Magicians and mentalists frequently use grand gestures, animated movement, music, and chatter to distract attention from a sneaky maneuver that sets up the trick. For example, a mentalist may engage in lively conversation while secretly writing something on his palm. Or he may dramatically throw his jacket on a chair to cover up a hidden assistant in the audience.[20]

Cold reading

editThis technique involves making calculated guesses and drawing logical conclusions about a person by carefully observing their appearance, responses, mannerisms, vocal tones, and other unconscious reactions. Mentalists leverage these cues along with high probability assumptions about human nature to come up with surprisingly accurate character insights and details about someone. They can then present this as if they magically knew the information through psychic powers.[21]

Hot reading

editHot reading refers to the practice of gathering background information about the audience or participants before doing a mentalism act or seance. Mentalists can then astonish spectators by revealing something they could not possibly have known otherwise. However, doing hot readings without informing the audience is considered unethical. Ethical mentalists only do hot readings if they explicitly disclose it, or do it for entertainment with the participant's consent.

Psychological manipulation

editMaster mentalists have an in-depth understanding of human psychology which allows them to subtly manipulate thoughts, emotions, and behaviors. They use verbal suggestion, social pressure, visual cues and mental framing to influence perceptions and reactions. This lets them guide participants towards the responses, outcomes or choices they want. For instance, a mentalist may hint that choosing a certain number will lead to something positive.

Dual reality

editThis principle involves structuring a routine to present different experiences to the observer versus the participant. For example, a mentalist may have an audience member pick a "random" card that is actually forced by the mentalist's assistant. The participant believes they freely chose any card, while the audience knows it's manipulated.

Subtle artistry

editThe most skilled mentalists ensure their performances seem completely natural, organic and unrehearsed even though they are carefully planned. They structure their acts, patter and effects to come across as pure luck, coincidence or chance rather than as clever illusions or tricks. This 'invisible' artistry maintains the mystique around mentalist performances.[22]

Performance approaches

editStyles of mentalist presentation can vary greatly. In this vein, Penn & Teller explain that "[m]entalism is a genre of magic that exists across a spectrum of morality."[9] In the past, at times, some performers such as Alexander[23] and Uri Geller[24][25][26] have promoted themselves as genuine psychics.

Some contemporary performers, such as Derren Brown, explain that their results and effects are from using natural skills, including the ability to master magic techniques and showmanship, read body language, and influence audiences with psychological principles, such as suggestion.[3] In this vein, Brown explains that he presents and stages "psychological experiments" through his performances.[27] Mentalist and psychic entertainer Banachek also rejects that he possesses any supernatural or actual psychic powers,[28] having worked with the James Randi Educational Foundation for many years to investigate and debunk fake psychics.[29] He is clear with the public that the effects and experiences he creates through his stage performance are the result of his highly developed performance skills and magic techniques, combined with psychological principles and tactics.[28][30]

Max Maven often presented his performances as creating interactive mysteries and explorations of the mysterious dimensions of the human mind.[31] He is described as a "mentalist and master magician"[32] as well as a "mystery theorist."[33] Other mentalists and allied performers also promote themselves as "mystery entertainers".[34]

There are mentalists, including Maurice Fogel, Kreskin, Chan Canasta, and David Berglas, who make no specific claims about how effects are achieved and may leave it up to the audience to decide, creating what has been described as "a wonderful sense of ambiguity about whether they possess true psychic ability or not."[35]

Contemporary mentalists often take their shows onto the streets and perform tricks to a live, unsuspecting audience. They do this by approaching random members of the public and ask to demonstrate so-called supernatural powers. However, some performers such as Derren Brown who often adopt this method of performance tell their audience before the trick starts that everything they see is an illusion and that they are not really "having their mind read." This has been the cause of a lot of controversy in the sphere of magic as some mentalists want their audience to believe that this type of magic is "real" while others think that it is morally wrong to lie to a spectator.[36]

Distinction from magicians

editProfessional mentalists generally do not mix "standard" magic tricks with their mental feats. Doing so associates mentalism too closely with the theatrical trickery employed by stage magicians. Many mentalists claim not to be magicians at all, arguing that it is a different art form altogether.[6][5] The argument is that mentalism invokes belief and imagination that, when presented properly, may allow the audience to interpret a given effect as "real" or may at least provide enough ambiguity that it is unclear whether it is actually possible to somehow achieve.[37][2] This lack of certainty about the limits of what is real may lead individuals in an audience to reach different conclusions and beliefs about mentalist performers' claims – be they about their various so-called psychic abilities, photographic memory, being a "human calculator", power of suggestion, NLP, or other skills. In this way, mentalism may play on the senses and a spectator's perception or understanding of reality in a different way than conjuring techniques utilized in stage magic.[38][2]

Magicians often ask the audience to suspend their disbelief, ignore natural laws, and allow their imagination to play with the various tricks they present. They admit that they are tricksters from the outset, and they know that the audience understands that everything is an illusion.[39][2] Everyone knows that the magician cannot really achieve the impossible feats shown, such as sawing a person in half and putting them back together without injury, but that level of certainty does not generally exist among the mentalist's audience. Still, other mentalists believe it is unethical to portray their powers as real, adopting the same presentation philosophy as most magicians. These mentalists are honest about their deceptions, with some referring to this as "theatrical mentalism".[40]

However, some magicians do still mix mentally-themed performance with magic illusions. For example, a mind-reading stunt might also involve the magical transposition of two different objects. Such hybrid feats of magic are often called mental magic by performers. Magicians who routinely mix magic with mental magic include David Copperfield, David Blaine, The Amazing Kreskin, and Dynamo.[citation needed]

Notable mentalists

edit- Lior Suchard

- The Amazing Kreskin

- Uri Geller

- Joseph Dunninger

- Derren Brown

- Alexander

- Theodore Annemann

- Banachek

- Keith Barry

- Guy Bavli

- David Berglas

- Paul Brook

- Akshay Laxman

- Chan Canasta

- Bob Cassidy

- The Clairvoyants

- Corinda

- Anna Eva Fay

- Glenn Falkenstein

- Maurice Fogel

- Haim Goldenberg

- Burling Hull

- Al Koran

- Nina Kulagina

- Max Maven

- Gerry McCambridge

- Alexander J. McIvor-Tyndall

- Wolf Messing

- Alain Nu

- Marc Paul

- Richard Osterlind

- The Piddingtons

- Oz Pearlman

- Princess Mysteria

- Marc Salem

- The Zancigs

Historical figures

editMentalism techniques have, on occasion, been allegedly used outside the entertainment industry to influence the actions of prominent people for personal and/or political gain. Famous examples of accused practitioners include:

- Erik Jan Hanussen, alleged to have influenced Adolf Hitler[41]

- Grigori Rasputin, alleged to have influenced Tsaritsa Alexandra[42]

- Wolf Messing, alleged to have influenced Joseph Stalin[43]

- Count Alessandro di Cagliostro, accused of influencing members of the French aristocracy in the Affair of the Diamond Necklace

In Albert Einstein's preface to Upton Sinclair's 1930 book on telepathy, Mental Radio, he supported his friend's endeavor to test the abilities of purported psychics and skeptically suggested: "So if somehow the facts here set forth rest not upon telepathy, but upon some unconscious hypnotic influence from person to person, this also would be of high psychological interest."[44] As such, Einstein here alluded to techniques of modern mentalism.

In popular culture

editSee also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b "Mentalism – Encyclopedia of Claims". JREF. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- ^ a b c d "What's the difference between magic and mentalism?". CW Magic. 2021. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- ^ a b Brown, Derren (2007). Tricks of the Mind. United Kingdom: Transworld Publishers.

- ^ "What is Mentalism?". Brut. Retrieved January 11, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Brennan, John T. (2007). Ghosts of Newport: Spirits, Scoundres, Legends and Lore. History Press.

- ^ a b c Vanishing, Inc. (2021). What is Mentalism?.

- ^ "Psychic Entertainers Association : Application". www.p-e-a.org. Retrieved January 11, 2021.

- ^ "Bio". Banachek. Retrieved January 11, 2021.

- ^ a b Penn & Teller (2021). Arts and Entertainment: Mentalist or Crook?. MasterClass.

- ^ Roeper, Richard (March 19, 2015). "'An Honest Liar': How the Amazing Randi debunked psychic frauds". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- ^ Green, Adam (September 26, 2019). "How Derren Brown Remade Mind Reading for Skeptics". The New Yorker. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- ^ Cassidy, Bob: "Fundamentals of Professional Mentalism". Lybrary, 2007. pp. 7–9.

- ^ Grant, Elihu (1923). "Oracle in the Old Testament". The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures. 39 (4): 257–281. doi:10.1086/369998. ISSN 1062-0516. JSTOR 528285. S2CID 170460547.

- ^ Flower, Michael Attyah (2008). The Seer in Ancient Greece (PDF). Berkeley and Los Angeles, California: University of California Press.

- ^ Achterberg, J. (2002). Imagery in Healing: Shamanism and Modern Medicine. Shambhala. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-8348-2629-8. Retrieved June 1, 2023.

- ^ Randi, James (1995). "An Encyclopedia of Claims, Frauds, and Hoaxes of the Occult and Supernatural". St. Martin's Press. Retrieved March 28, 2008.

- ^ ""Quicker Than CeeDee Lamb": DK Metcalf Once Fell Prey to Mentalist Oz Pearlman's Mind Boggling Passcode Trick". Sports Rush. August 13, 2023. Retrieved May 19, 2024.

- ^ Wind, Asi (2021). Before We Begin. Vanishing Inc. ISBN 9781954243002.

- ^ "glossary". Lior Suchard. October 25, 2021. Retrieved May 19, 2024.

- ^ "art of misdirection". katherine mills. July 18, 2019. Retrieved May 19, 2024.

- ^ "how does cold reading work". Vanishing Inc Magic. Retrieved May 19, 2024.

- ^ 'Mentalism Techniques': Techniques to master mentalism, March 2024, retrieved March 30, 2024

- ^ "Alexander – The man who knows". ForzoniMagic. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- ^ "The Psychic ... and the Skeptic : Uri Geller and James Randi have fought each other for nearly 20 years. Now they're at it again". Los Angeles Times. July 27, 2020. Archived from the original on July 27, 2020. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- ^ AFP. "Uri Geller offers UK his 'psychic powers' in job bid". www.timesofisrael.com. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- ^ Larimer, Sarah. "That time the CIA was convinced a self-proclaimed psychic had paranormal abilities". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- ^ Derren Brown (August 26, 2019). "Mentalism, mind reading and the art of getting inside your head". www.youtube.com. Retrieved January 11, 2021 – via YouTube.

- ^ a b "Project Alpha". Banachek. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- ^ Cerrado, Derrick (November 13, 2009). "Banachek – Mentalism and Skepticism | Point of Inquiry". Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- ^ Measom, Tyler; Weinstein, Justin (November 2, 2014), An Honest Liar (Documentary, Biography, Comedy, History), James Randi, José Alvarez, Penn Jillette, Teller, Left Turn Films, Pure Mutt Productions, BBC Storyville, retrieved January 10, 2021

- ^ "All About Max ~ MaxMaven.com". www.maxmaven.com. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- ^ "Magician Max Maven's Thinking in Person Set for Off-Broadway Run | TheaterMania". www.theatermania.com. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- ^ "Max Maven, Mystery Theorist & Magician (EG8)". EG Conference. October 30, 2019. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- ^ "PSYCRETS British Society of Mystery Entertainers". PSYCRETS British Society of Mystery Entertainers. Retrieved January 11, 2021.

- ^ Landman, Todd (March 18, 2016). "Magic professor: magicians tap into what it means to be human". The Conversation. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- ^ "Is it wrong to work Magic?". Archived from the original on April 26, 2015. Retrieved April 12, 2015.

- ^ Mio (March 22, 2016). "Key Differences Between Mentalism and Magic". Magic by Mio. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- ^ Mio (March 22, 2016). "Key Differences Between Mentalism and Magic". Magic by Mio. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- ^ Mio (March 22, 2016). "Key Differences Between Mentalism and Magic". Magic by Mio. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- ^ Kimlat, Kostya. "Mentalist Magician". Kostya Kimlat the Business Magician. Retrieved February 14, 2024.

- ^ Gordon, Mel: "Hanussen: Hitler's Jewish Clairvoyant". Feral House, 2001

- ^ George King, The Last Empress: The Life and Times of Alexandra Feodorovna, Tsarina of Russia. Replica Books, 2001. ISBN 978-0735101043

- ^ Hamilton-Parker, Craig (December 1, 1996). "Medium with a message". Scotland on Sunday. p. 5.

- ^ Halpern, Paul (August 30, 2020). "Einstein and the Mentalists". Medium. Retrieved January 11, 2021.

Further reading

edit- H. J. Burlingame. (1891). Mind-Readers and Their Tricks. In Leaves from Conjurers' Scrap books: Or, Modern Magicians and Their Works. Chicago: Donohue, Henneberry & Co. pp. 108–127

- Derren Brown (2007). Tricks of the Mind. Transworld Press. United Kingdom.

- Steve Drury (2016). Beyond Knowledge. Drury. ISBN 978-1326544867

- Max Maven (1992). Max Maven's Book of Fortunetelling. Prentice Hall General; 1st edition. ISBN 0135641217

- William V. Rauscher. (2002). Mind Readers: Masters of Deception. Mystic Light Press.

- Barry H. Wiley. (2012). The Thought Reader Craze: Victorian Science at the Enchanted Boundary. McFarland. ISBN 978-0786464708

External links

edit- Media related to Mentalists at Wikimedia Commons