I Walked with a Zombie is a 1943 American horror film directed by Jacques Tourneur and produced by Val Lewton for RKO Pictures. It stars James Ellison, Frances Dee, and Tom Conway, and follows a Canadian nurse who travels to care for the ailing wife of a sugar plantation owner in the Caribbean, where she witnesses Vodou rituals and possibly encounters the walking dead. The screenplay, written by Curt Siodmak and Ardel Wray, is based on an article of the same title by Inez Wallace, and also partly reinterprets the narrative of the 1847 novel Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë.[1][2]

| I Walked with a Zombie | |

|---|---|

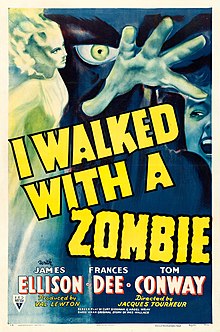

Theatrical release poster by William Rose | |

| Directed by | Jacques Tourneur |

| Written by | |

| Based on |

|

| Produced by | Val Lewton |

| Starring | |

| Narrated by | Frances Dee |

| Cinematography | J. Roy Hunt |

| Edited by | Mark Robson |

| Music by | Roy Webb |

| Distributed by | RKO Radio Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 69 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

The film premiered in New York City on April 21, 1943, before receiving a wider theatrical release later that month. It has been analyzed for its themes of slavery and racism, and for its depiction of beliefs associated with African diaspora religions, particularly Haitian Vodou. Though it received mixed reviews upon its release, retrospective assessments of the film have been more positive.

Plot

editOn a snowy Ottawa day, young nurse Betsy Connell is interviewed to care for the wife of Paul Holland, a sugar plantation owner on Saint Sebastian, a Caribbean island. Although she is told little about the patient, Betsy looks forward to the warmer climate and accepts the job, laughing it off when asked if she believes in witchcraft.

The coachman who takes Betsy to Paul's house, Fort Holland, tells her Saint Sebastian's Afro-Caribbean population is descended from slaves brought by Paul's ancestors. At her first dinner, Betsy meets Paul's younger half-brother and employee, Wesley Rand, who, though good-humored, clearly resents Paul. She encounters Jessica, her patient, wandering the grounds that night, and is initially frightened by the nonverbal, affectless woman, who, as Dr. Maxwell later informs Betsy, was left without the willpower to speak or act by herself after a tropical fever irreparably damaged her spinal cord.

Betsy learns from a calypso musician's song that Paul kept Jessica from running away with Wesley right before she became sick. The issues surrounding Jessica have driven Wesley to drink, and the simmering tension between him and Paul frequently threatens to boil over. Paul apologizes to Betsy for bringing her to Saint Sebastian and admits he feels responsible for Jessica's condition. Betsy, who has fallen in love with Paul, becomes determined to make him happy by curing Jessica and gets him to agree to a risky insulin shock treatment. When that fails, Alma, Paul's maid, convinces Betsy to take Jessica to be healed by the houngan (Vodou priest) at the houmfort (Vodou temple).

After a man dressed in black performs a ritual dance using a small sword, Betsy gets in line at the houmfort to ask the spirit Damballa to heal Jessica. Instead, she is pulled inside a hut and is shocked to see Mrs. Rand, Paul and Wesley's mother, who works with Maxwell. Mrs. Rand reveals that, with the houngan's knowledge, she has been telling the islanders that Vodou spirits speak through her so they will comply with her medical and sanitary recommendations. Meanwhile, Jessica attracts the attention of the man in black, who stabs her in the arm. She does not bleed, causing murmurs of "zombie" among the onlookers, and Mrs. Rand tells Betsy to take Jessica home. An upset Paul greets them, but he softens when he learns Betsy was trying to help him, and lets her know he no longer loves his wife.

The Voudou congregation demands Jessica be delivered to them for further ritualistic tests, so Maxwell and local authorities want her sent to an asylum on a different island. Paul resists because Wesley wants Jessica to stay, and he tells Betsy to return to Canada before he makes her as unhappy as he made Jessica before her illness. At night, Carrefour, a zombie who guards a crossroads, is sent to retrieve Jessica, approaching Betsy instead after she puts on Jessica's robe, but Mrs. Rand orders him to leave.

Maxwell visits to report there will be an official investigation to determine Jessica's fate. Faced with scandal, and with her sons at each other's throats, Mrs. Rand says Jessica is not sick or insane, but dead, as she went to the houmfort the night Jessica tried to run away with Wesley and, possessed, asked the houngan to make Jessica a zombie. Only Wesley believes the story, and he later asks Betsy to euthanize Jessica, though Betsy refuses.

Using a small effigy of Jessica, the man in black and the houngan attempt to draw her to the houmfort. Paul and Betsy stop her the first time, but Wesley helps her the second, following with an arrow removed from a garden statue depicting Saint Sebastian, "Ti-Misery", that was once the figurehead of a Holland-family slave ship. The man in black stabs the doll with a pin to mirror Wesley stabbing Jessica with the arrow, who is pursued slowly by Carrefour as he carries her body into the sea. Jessica and Wesley are discovered floating in the surf; their bodies are brought back to Fort Holland. A voice-over condemns Jessica as an evil woman who led Paul astray, but asks God's forgiveness for the dead, Ti-Misery looming in the background. Betsy and Paul console each other.

Cast

edit- Frances Dee as Betsy Connell

- Tom Conway as Paul Holland

- James Ellison as Wesley Rand

- Edith Barrett as Mrs. Rand

- James Bell as Dr. Maxwell

- Christine Gordon as Jessica Holland

- Theresa Harris as Alma

- Sir Lancelot as Calypso Singer

- Darby Jones as Carrefour[a]

- Jeni Le Gon as Dancer[5]

- Rita Christiani as a friend of Melise (uncredited)[5]

- Jieno Moxzer as the sabreur (uncredited)[5]

Production

editDevelopment

editRKO executives, rather than producer Val Lewton, chose the film's title,[6] which was taken from an article of the same name written by Inez Wallace for American Weekly Magazine.[7] Whereas the article detailed Wallace's experience meeting "zombies", by which she meant, not the literal living dead, but rather people she encountered working on a plantation in Haiti whose vocal cords and cognitive abilities had been impaired by drug use, rendering them obedient servants who understood and followed simple orders,[8] Lewton asked screenwriters Curt Siodmak and Ardel Wray to research the practices of Haitian Vodou and use Charlotte Brontë's Jane Eyre as a model for the narrative structure,[9] purportedly proclaiming that he wanted to make a "West Indian version of Jane Eyre."[10] Siodmak's initial draft, which was revised significantly by Wray and Lewton, revolved around the wife of a plantation owner who is made into a zombie to prevent her from leaving him and moving to Paris.[11]

Casting

editAnna Lee was originally slated for the role ultimately played by Frances Dee, but had to bow out due to another commitment.[12] Dee received $6,000 for her performance in the film,[13] and Darby Jones was paid, based on his weekly contract salary of $450, $75 a day, totaling $225 for his three days of work.[13]

Filming

editPrincipal photography for the film, which Wray described it as being shot on a "shoestring budget",[11] began October 26, 1942,[11] and wrapped less than a month later, on November 19.[14]

Release

editTheatrical distribution

editI Walked with a Zombie had its theatrical premiere on April 8, 1943, in Cleveland, Ohio, which was the hometown of Inez Wallace, the author of the film's source material.[15] It opened in New York City on April 21, before expanding wide on April 30,[16] and continued to screen in North American theaters until as late as December 19, when it was at the Rialto in Casper, Wyoming.[17]

The film was re-released in the United States by RKO in 1956, opening in Los Angeles in July[18] and screening nationwide throughout the fall and into late December.[19][20]

Home media

editThe film was released on DVD by Warner Home Video in 2005 as part of "The Val Lewton Horror Collection", a 9-film box set, on the same disc as The Body Snatcher (1945).[21]

In 2024, The Criterion Collection announced a 4K/Blu-ray release of the film as part of the double feature set, I Walked with a Zombie / The Seventh Victim: Produced by Val Lewton.[22]

Reception

editContemporaneous reviews

editInitial reception for the film was mixed. While The New York Times was critical, calling it "a dull, disgusting exaggeration of an unhealthy, abnormal concept of life",[23] Wanda Hale of the New York Daily News awarded it two-and-a-half out of three stars and praised it as a "spine-chilling horror film".[24] Whereas The Boston Globe felt the film "gets nowhere in the telling and finishes its overdone melodramatics with a most unconvincing climax",[25] a reviewer in Albany, New York, said it "rigs up a great atmosphere for the haunt and holler audience and, compared with Cat People, the movie with which it is mentioned most often in publicity, it is a success."[26]

Retrospective assessments

editOn review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, the film has an approval rating of 85% based on 41 reviews, with an average score of 8.1/10; the site's "critics consensus" reads: "Evocative direction by Jacques Tourneur collides with the low-rent production values of exploitateer Val Lewton in I Walked with a Zombie, a sultry sleeper that's simultaneously smarmy, eloquent and fascinating."[27]

Author and film critic Leonard Maltin gave the film three-and-a-half out of four stars, praising its atmosphere and story and calling it an "Exceptional Val Lewton chiller".[28] Dennis Schwartz awarded the film an "A" grade, praising the atmosphere, the story, and Tourneur's direction.[29] TV Guide awarded the film their highest rating of five out of five stars, calling it "an unqualified horror masterpiece".[30] Alan Jones of Radio Times gave the film four out of five stars, writing: "Jacques Tourneur's direction creates palpable fear and tension in a typically low-key nightmare from the Lewton fright factory. The lighting, shadows, exotic setting and music all contribute to the immensely disturbing atmosphere, making this stunning piece of poetic horror a classic of the genre."[31]

In 2007, Stylus Magazine named I Walked with a Zombie the fifth best zombie film of all time.[32]

In 2021, Apichatpong Weerasethakul gave the name of Jessica Holland to the main heroine of Memoria, in tribute to I Walked with a Zombie.[33]

Themes and interpretations

editSlavery and racism

edit"Carre-Four must have confronted audiences that summer as an especially charged figure, even if his exact significance requires after-the-fact interpretation. An iconography of racial violence haunts his scenes even amid the erasure of rope-and-gun specifics. Alone, dead, beautifully and self-consciously staged, facing the audience directly and meant for its inspection alone in a story explicitly about a people's long memories of slavery, he is disquietingly insisted upon."

Historian and author Alexander Nemerov asserted that I Walked with a Zombie uses stillness as a metaphor for slavery "in ways that center on Carre-Four",[35] who, like Ti-Misery, "the slave ship's figurehead, is a static and insentient figure". He wrote that the character personifies a link between slavery and the concept of zombies, citing anthropologist Wade Davis, who said: "Zombis do not speak, cannot fend for themselves, do not even know their names. Their fate is enslavement."[36] Numerov added that Carrefour "suggests the violent subjugation and the emergent power of blacks" during World War II, calling the character "a simultaneous portrayal of strength and victimization",[34] and characterized Darby Jones' portrayal as a "monumental [...] dominant screen presence"[37] that, in the context of the war and the American Double V campaign, "equaled the performances of far more famous black actors in the depiction of a charged conceit: the black man standing alone."[13]

Numerov stated that both Carrefour and Ti-Misery "conjure the lynching of a black man",[36] pointing to the film's final shot, which is of Ti-Misery, as particularly establishing the figurehead as an image reminiscent of lynching.[36] Of the narration in the final scene, which is the only narration in the film not spoken by Betsy, he wrote that the line "pity those who are dead, and wish peace and happiness to the living" is "meant to encompass the white characters [...] But the decision to end with the sculpture of Ti Misery and the voice of the black man directs these sentiments back to 'the misery and pain of slavery.'"[38] As the film was released during World War II, Nemerov said "the film's final words and image implied a Willkie-style acknowledgement of injustice at home."[38]

Writer Lee Mandelo characterized Ti-Misery as a symbolic representation of "brutality and intense suffering".[39] He lamented that the film's initial thematic arc, which he wrote made "a few grasps for a more sensitive commentary", was "flipped around to discuss the 'enslavement' of the beautiful white woman, Jessica, who has been either made a zombie or is an up-and-moving catatonic", saying it was "flinch-inducing, as it takes the suffering of the black population of the island and gives it over to a white woman".[39]

Both Nemerov and Mandelo discussed the references in the film to the residents of Saint Sebastian, due to the island's history of slavery, still crying at the births of children and laughing at funerals. Mandelo called this "a cultural tradition that comes from a life without freedom".[35][39]

Writer Jim Vorel asserted that "Although the setting of the film is a post-slavery island of Saint Sebastian, the film's constant visual motifs of bondage and servitude never allow the viewer to forget the horrors of their not-so-distant past."[40] Regarding Carrefour, writer Vikram Murthi asserted that "It's not his visage that unsettles, but rather the history beneath his face. It's no wonder that neither the Hollands nor Betsy can hardly bear to stare at him; he reflects the corrosion of their collective soul."[4]

Voodoo

editVorel argued that the film approaches the beliefs associated with African diaspora religions, particularly Haitian Vodou, in a more thoughtful manner than earlier films like White Zombie (1932).[40] He wrote that I Walked with a Zombie "not only depict[s] them with surprising accuracy and dignity, but consider[s] how those beliefs could be co-opted by the white man as one more element of control over the lives of the island inhabitants."[40]

Nemerov compared the setting of the houmfort, with its black attendees and musical performances, to a Harlem nightclub[41] and noted the film's depiction of a performance of the Haitian Vodou song "O Legba", provided to the film by folklorist Leroy Antoine, as evidence of the research conducted by the filmmakers.[5] Additionally, he wrote that when Alma instructs Betsy on how to reach the houmfort, "her description of Carre-Four as a 'god' sounds almost like 'guard,' and the two words combine not only to define his voodoo role, guardian of the crossroads, but also to assert the importance of his triviality: like the doorman at an actual club, he is a guard who holds godlike power."[42]

Haitian Vodou researcher Laënnec Hurbon felt the "director displayed Haitian voodoo as a series of bizarre practices, chief among them the sorcerers' ability to kill people and then reanimate them in a state of living death. The idea flourished."[43]

See also

editNotes

editReferences

edit- ^ Bansak 2003, pp. 146–147.

- ^ Nochimson, Martha P. (August 2007). "I Walked With a Zombie". Senses of Cinema. No. 44.

- ^ Nemerov 2005, p. 97–98, 102–108, 112–119.

- ^ a b Murthi, Vikram (September 2, 2015). "Criticwire Classic of the Week: 'I Walked With a Zombie'". IndieWire. Retrieved June 29, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Nemerov 2005, p. 118.

- ^ Bansak 2003, p. 143.

- ^ Wallace 1986, pp. 95–102.

- ^ Bansak 2003, p. 146.

- ^ Bowen, Peter (April 21, 2010). "I Walked with a Zombie". Focus Features. Archived from the original on September 27, 2011.

- ^ Bansak 2003, p. 145.

- ^ a b c Bansak 2003, p. 147.

- ^ Hanson & Dunkleberger 1999, p. 1127.

- ^ a b c Nemerov 2005, p. 114.

- ^ Bansak 2003, p. 149.

- ^ "Cleveland Views Local Girls' Film". The Gazette. Montreal, Quebec. April 20, 1943. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "I Walked with a Zombie". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Los Angeles, California: American Film Institute. Archived from the original on December 4, 2018. Retrieved December 4, 2018.

- ^ "'I Walked with a Zombie' and 'Souls at Sea' at the Rialto". Casper Star-Tribune. Casper, Wyoming. December 19, 1943. p. 7 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "West Coast Fox Theatres program". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles, California. July 3, 1956. p. 12 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "New, Old Films Vie For Orlando Interest This Week". Orlando Sentinel. Orlando, Florida. December 23, 1956. p. 8-C – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Today's Film Showtimes". Democrat and Chronicle. Rochester, New York. December 22, 1956. p. 4 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Erickson, Glenn (September 9, 2005). "DVD Savant Review: The Val Lewton Collection". DVD Talk. Archived from the original on July 28, 2012.

- ^ "I Walked with a Zombie / The Seventh Victim: Produced by Val Lewton". The Criterion Collection. Retrieved July 23, 2024.

- ^ "At the Rialto - The New York Times". The New York Times. 22 April 1943. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- ^ Hale, Wanda (April 22, 1943). "'China' Good War Film On Paramount Screen". New York Daily News. p. 44 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "New Films". The Boston Globe. Boston, Massachusetts. April 22, 1943. p. 21 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Bradt, Clif. "Voodooland Featured in Film at Grand." The Knickerbocker News (Albany, NY), 15 May 1943.

- ^ "I Walked with a Zombie (1943) - Rotten Tomatoes". Rotten Tomatoes.com. Flixster. Retrieved 20 November 2022.

- ^ Leonard Maltin (3 September 2013). Leonard Maltin's 2014 Movie Guide. Penguin Publishing Group. p. 716. ISBN 978-1-101-60955-2.

- ^ Schwartz, Dennis (5 August 2019). "I Walked With a Zombie". dennisschwartzreviews.com. Retrieved 28 October 2022.

- ^ "I Walked With A Zombie - Movie Reviews and Movie Ratings". TV Guide.com. TV Guide. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- ^ Jones, Alan. "I Walked with a Zombie – review". Radio Times.com. Alan Jones. Retrieved 28 October 2022.

- ^ Stylus Magazine's Top 10 Zombie Films of All Time – Movie Review – Stylus Magazine

- ^ Uzal, Marcos (2021-07-16). "Cannes 2021 Memoria de Apichatpong Weerasethakul Des Trous dans la tête". Cahiers du cinéma. Retrieved 2024-01-30.

- ^ a b Nemerov 2005, p. 112.

- ^ a b Nemerov 2005, p. 103.

- ^ a b c Nemerov 2005, p. 104.

- ^ Nemerov 2005, p. 99, 116.

- ^ a b Nemerov 2005, p. 108.

- ^ a b c Mandelo, Lee (February 6, 2020). "Changing Metaphors: On I Walked With a Zombie (1943)". Tor.com. Retrieved June 29, 2021.

- ^ a b c Vorel, Jim (August 16, 2019). "The Best Horror Movie of 1943: I Walked With a Zombie". Paste. Retrieved June 29, 2021.

- ^ Nemerov 2005, p. 118–119.

- ^ Nemerov 2005, p. 119.

- ^ Hurbon 1995, p. 59.

Bibliography

edit- Bansak, Edmund G. (2003). Fearing the Dark: The Val Lewton Career. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-1709-4.

- Fujiwara, Chris (2015) [2001]. Jacques Tourneur: The Cinema of Nightfall. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-6561-9.

- Hanson, Patricia K.; Dunkleberger, Amy (1999). AFI: American Film Institute Catalog of Motion Pictures Produced in the United States : Feature Films 1941-1950 Indexes. Vol. 2. Los Angeles, California: University of California Press. ISBN 0520215214.

- Hurbon, Laënnec (1995). Voodoo: Truth and Fantasy. 'New Horizons' series. Translated by Frankel, Lory. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-30049-7.

- Nemerov, Alexander (2005). Icons of Grief: Val Lewton's Home Front Pictures. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520241008.

- Wallace, Inez (1986). "I Walked with a Zombie". In Haining, Peter (ed.). Zombie! Stories of the Walking Dead. London: W.H. Allen. ISBN 978-0-426-20161-8.