I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang is a 1932 American pre-Code crime tragedy film directed by Mervyn LeRoy and starring Paul Muni as a convicted man on a chain gang who escapes to Chicago. It was released on November 10, 1932. The film received critical acclaim and was nominated for three Academy Awards including Best Picture and Best Actor for Muni.

| I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang | |

|---|---|

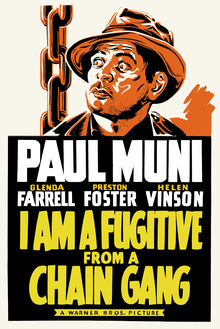

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Mervyn LeRoy |

| Screenplay by | Howard J. Green Brown Holmes |

| Based on | I Am a Fugitive from a Georgia Chain Gang! 1932 book by Robert E. Burns |

| Produced by | Hal B. Wallis |

| Starring | Paul Muni Glenda Farrell Helen Vinson Noel Francis |

| Cinematography | Sol Polito |

| Edited by | William Holmes |

| Music by | Bernhard Kaun |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. |

Release date |

|

Running time | 93 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $228,000[2] |

| Box office | $1,599,000[2] |

The film was written by Howard J. Green and Brown Holmes from Robert Elliott Burns's 1932 autobiography of a similar name I Am a Fugitive from a Georgia Chain Gang! originally serialized in the True Detective magazine.[3] The true life story was later the basis for the television movie The Man Who Broke 1,000 Chains (1987) starring Val Kilmer.[4]

In 1991, the film was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[5][6]

Plot

editWhite American sergeant James Allen returns to civilian life after World War I. He has served with distinction, earning a medal from Allied governments for his bravery, but his war experience has made him restless. His mother and minister brother feel Allen should be grateful for a tedious office clerk job. When he announces that he wants to enter the construction industry and improve society as an engineer, his brother reacts with outrage, but his mother regretfully accepts his ambitions.

He leaves home to find work, but unskilled labor is plentiful, and it is hard for him to find a job. Allen sinks slowly into poverty. In an unnamed Southern state (the events upon which the film was based took place in Georgia), Allen visits a diner with an acquaintance, who forces him at gunpoint to participate in a robbery. The police arrive and shoot and kill his friend. Allen panics and attempts to flee but is caught immediately.

Allen is tried and sentenced to prison with hard labor. He is quickly exposed to the brutal conditions of life on a chain gang. The work is agonizing, and the guards are cruel and sadistically whip prisoners for poor performance. Allen makes friends among the gang members, most notably Bomber Wells, an older murderer and chain gang veteran. The two conspire to stage a breakout.

While working on a railroad, Allen receives assistance from Sebastian T. Yale, a powerfully built prisoner who damages Allen's shackles by hammering them with Allen's ankles still inside. The following Monday, while on a "bathroom break," Allen slips out of his chains and runs. Armed guards and bloodhounds give chase, but Allen evades them by changing clothes and hiding at the bottom of a river. He makes it to a nearby town, where he is given money for a train ticket and a room for the night by one of Bomber's friends.

Allen makes his way to Chicago, where he obtains a job as a manual laborer and uses his knowledge of engineering and construction to rise to a position of importance within a construction company. Along the way, he becomes romantically involved with his landlady, Marie Woods. Allen grows to loathe Marie, but she discovers his secret and blackmails him into an unhappy marriage.

Trying to forget his troubles, he attends a high-society party at the invitation of his superiors and meets and falls in love with a younger woman named Helen. Marie betrays him to the authorities when he asks for a divorce. Allen describes the inhumane conditions of the chain gangs to the press, becoming national news. Many common citizens express their disgust with the chain gangs and their sympathy for a reformed man such as Allen, while editorials written by Southerners describe his continued freedom as a violation of "state's rights."

The governor of Illinois refuses to release Allen to the custody of the Southern state. Its officials offer Allen a deal: return voluntarily and receive a pardon after 90 days of easy clerical labor. Allen accepts, only to find the proposals were a ruse; he is sent to a chain gang, where he languishes for another year after being denied a pardon.

Reunited with Bomber, Allen decides to escape once more. The two steal a dump truck loaded with dynamite from a work site. While leaning out of his seat to taunt pursuing guards, Bomber gets shot. He takes some of the dynamite, lights it, and throws it at a police car, causing a minor landslide. Shortly afterward, Bomber falls from the truck and dies, causing Allen to stop the vehicle. Allen then uses more dynamite to blow up a bridge he just crossed, allowing him to make a close escape. Allen makes his way north again, evading a relentless manhunt.

Months later, he visits Helen in Chicago to wish her a permanent goodbye. Tearfully, she asks, "Can't you tell me where you're going? Will you write? Do you need any money?" Allen repeatedly shakes his head as he backs away. Finally, Helen says, "But you must, Jim. How do you live?" Allen's face is barely visible in the surrounding gloom as he replies, "I steal," disappearing into the darkness.

Cast

edit- Paul Muni as James Allen

- Glenda Farrell as Marie

- Helen Vinson as Helen

- Noel Francis as Linda

- Preston Foster as Pete

- Allen Jenkins as Barney Sykes

- Berton Churchill as the Judge

- Edward Ellis as Bomber Wells

- David Landau as the Warden

- Hale Hamilton as Rev. Allen

- Sally Blane as Alice

- Louise Carter as Mrs. Allen

- Jack LaRue as Ackerman (uncredited)

- Walter Long as Blacksmith (uncredited)

- Charles Middleton as Train Conductor (uncredited)

Development and production

editThe film was based on the book I Am a Fugitive from a Georgia Chain Gang! (1932) written by Robert Elliott Burns and published by Vanguard Press.[7] The book recounts Burns' service on a chain gang while imprisoned in Georgia in the 1920s, his subsequent escape and the furor that developed. The story was first published in January 1932, and serialized in True Detective mysteries magazine.

Despite Jack L. Warner's and Darryl F. Zanuck's interest in adapting Burns's book, the Warner Bros. story department voted against it with a report that concluded: "[T]his book might make a picture if we had no censorship, but all the strong and vivid points in the story are certain to be eliminated by the present censorship board." The story editor's reasons were mostly related to the story's violence and the uproar that was sure to explode in the Deep South. In the end, Warner and Zanuck had the final say and approved the project.[8][9]

Roy Del Ruth, the highest-paid director at Warner Bros., was assigned to direct, but he refused the assignment. In a lengthy memo to supervising producer Hal B. Wallis, Del Ruth explained his decision: "This subject is heavy and morbid...there is not one moment of relief anywhere." Del Ruth further argued that the story "lacks box-office appeal," and that offering a depressing story to the public seemed ill-timed, given the harsh reality of the Great Depression outside the walls of the local neighborhood cinema. Mervyn LeRoy, who was at that time directing 42nd Street (released in 1933), dropped out of the shooting and left the reins to Lloyd Bacon.

LeRoy cast Paul Muni in the role of James Allen after seeing him in a stage production of Counsellor at Law. Muni was not impressed with LeRoy upon first meeting him in the Warner Burbank office, but Muni and LeRoy became close friends. LeRoy was present at Muni's funeral in 1967 along with Muni's agent.

To prepare for the role, Muni conducted several intensive meetings with Robert E. Burns in Burbank to learn how Burns walked and talked, in essence, to catch "the smell of fear." Muni stated to Burns: "I don't want to imitate you; I want to be you."[10] Muni set the Warner Bros. research department on a quest to procure every available book and magazine article about the penal system. He also met with several California prison guards, even one who had worked on a Southern chain gang. Muni fancied the idea of meeting with a guard or warden still working in Georgia, but Warner studio executives quickly rejected his suggestion.

The final lines in the film, "But you must, Jim. How do you live? I steal", are among the most famous closing lines in American film.[11] Director Mervyn LeRoy later claimed that the idea for James' retreat into darkness came to him when a fuse blew on the set, but it had been written into the script.[11]

Box office

editAccording to Warner Bros. Records, the film earned $650,000 domestically and $949,000 foreign, making it the studio's third-highest success of 1932-33 after Gold Diggers of 1933 and Forty Second Street.[2]

Critical reception

editOn the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, the film has an approval rating of 96%, based on reviews from 27 critics.[12]

Variety reviewer Abel Green wrote in November 1932 that it "is a picture with guts. It grips with its stark realism and packs lots of punch." And that "The finale is stark in its realism." The review said, "Muni turns in a pip performance." Variety also included a "Miniature" and "The Woman's Angle" reviews.[13][14]

Frederick James Smith in Liberty in November 1932 gave the film the top score of 4 stars, "extraordinary". "Paul Muni is splendid as the chain-gang victim. All the other roles are well done, but they are incidental to Muni and Mervyn Le Roy's tense, vigorous direction."[15]

The New Republic wrote in December 1932 that it "is one of the finest to come from Hollywood in many a day. It tells with unflinching realism how chain-gang prisoners are treated and at the same time through its direction and acting it is raised far above the level of mere journalistic exposure. It will bring home the conditions among prisoners to millions of persons".[16]

Jeremiah Kipp of Slant Magazine wrote in 2005, "Th[e] soul-crushing horrors of slave labor in the penal system are neatly interwoven into a highly gripping plot." But Kipp thought, "It feels more like an uncompromising prison film than a message movie, so its frequent heavy-handedness seems more like unabashed pulp rather than sanctimony."[17]

Kim Newman wrote in 2006 for Empire, "The most powerful of Warner Brothers’ early 1930s ‘social problem’ films, this indictment of organised cruelty remains potent, hard-hitting melodrama." And he said it was a "Suprisingly [sic] no-holds-barred portrait of institutional bullying for such an early film."[18]

Impact on American society

editThe film is among the first examples of cinema used to garner sympathy for imprisoned convicts without divulging the actual crimes of the convicts. American audiences began to question the legitimacy of the U.S. legal system,[19] and in January 1933, the film's protagonist Robert Elliott Burns, who was still imprisoned in New Jersey, and several other chain gang prisoners nationwide in the U.S., were able to appeal and were released.[20] In January 1933, Georgia chain gang warden J. Harold Hardy, who was also made into a character in the film, sued the studio for one million dollars for displaying "vicious, brutal and false attacks" against him in the film.[21]

Awards and nominations

editAcademy Award Nominations:[22]

National Board of Review Award:

- 1932 – Best Picture

Other Wins:

- 1991 – National Film Registry

References

edit- ^ "Screen Notes". New York Times. November 10, 1932.

- ^ a b c Warner Bros financial information in The William Schaefer Ledger. See Appendix 1, Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, (1995) 15:sup1, 1-31 p 13 DOI: 10.1080/01439689508604551

- ^ Marr, John. "True Detective, R.I.P." Stim.com. Retrieved January 26, 2016.

- ^ McGee, Scott (2014). "I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang". Turner Classic Movies. Turner Entertainment Networks, Inc. Retrieved November 5, 2022.

- ^ "Complete National Film Registry Listing". Library of Congress. Retrieved November 16, 2020.

- ^ Kehr, Dave (September 26, 1991). "U.S. FILM REGISTRY ADDS 25 'SIGNIFICANT' MOVIES". chicagotribune.com. Retrieved November 16, 2020.

- ^ "A Fugitive From Georgia's Prison System; I Am a Fugitive from a Georgia Chain Gang. By Robert E. Burns. Introduction by the Rev. Vincent G. Burns 257 pp. New York: The Vanguard Press. . New York Times, January 31, 1932. (Retrieved April 28, 2017.)

- ^ "I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang". www.tcm.com. Retrieved April 11, 2022.

- ^ Schatz, Thomas (June 2, 2015). The Genius of the System: Hollywood Filmmaking in the Studio Era. Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 978-1-62779-645-3.

- ^ Lawrence, Jerome. "Chapter 16" Actor, The Life and Times of Paul Muni. G.P. Putnam's Sons, New York, 1982

- ^ a b O'Connor, John E. "Introduction: Warners Finds Its Social Conscience." I Am a Fugitive From a Chain Gang. Ed. John E. O'Connor University of Wisconsin Press, 2005

- ^ "I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang". Rotten Tomatoes.

- ^ Green, Abel (November 15, 1932). "Variety". Media History Digital Library Media History Digital Library. New York, NY: Variety Publishing Company.

{{cite magazine}}: Cite magazine requires|magazine=(help) - ^ Variety Staff (January 1, 1932). "I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang". Variety. Retrieved April 9, 2022.

- ^ "A Success in Chains". Liberty. Vol. 09, no. 48. November 26, 1932. p. 32.

- ^ The New Republic 1932-12-21: Vol 73 Iss 942. New Republic. December 21, 1932.

- ^ Kipp, Jeremiah (May 22, 2005). "Review: I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang". Slant Magazine. Retrieved April 9, 2022.

- ^ "I Am a Fugitive From a Chain Gang Review". Empire. June 1, 2006.

- ^ "States & Cities: Fugitive". Time. December 26, 1932. Archived from the original on January 14, 2009. Retrieved May 4, 2010.

- ^ "States & Cities: Fugitive Free". Time. January 2, 1933. Archived from the original on January 14, 2009. Retrieved May 4, 2010.

- ^ "Milestones, Jan. 16, 1933". Time. January 16, 1933. Archived from the original on January 14, 2009. Retrieved May 4, 2010.

- ^ "The 6th Academy Awards (1934) Nominees and Winners". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Retrieved August 7, 2011.

Further reading

edit- Green, Howard J.; Holmes, Brown; Gibney, Sheridan (1981). O'Connor, John E.; Balio, Tino (eds.). I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang. Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-299-08754-8. Introduction: Warners Finds Its Social Conscience; Screenplay

- Burns, Robert E. (1932). I Am a Fugitive from a Georgia Chain Gang!. University of Georgia Press. ISBN 978-0-8203-1943-8.

- Nollen, Scott Allen (September 22, 2016). The Making and Influence of I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-6677-1.

- Lucia, Cynthia; Simon, Art; Grundmann, Roy (June 25, 2015). American Film History: Selected Readings, Origins to 1960. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-47516-4. Chapter 11: "As Close to Real Life as Hollywood Ever Gets", Richard Maltby

External links

edit- I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang at IMDb

- I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang at the TCM Movie Database

- ‹The template AllMovie title is being considered for deletion.› I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang at AllMovie

- I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang at Rotten Tomatoes

- I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang at TV Guide (1987 write-up was originally published in The Motion Picture Guide)

- I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang at Virtual History

- I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang essay by Daniel Eagan in America's Film Legacy: The Authoritative Guide to the Landmark Movies in the National Film Registry A&C Black, 2010 ISBN 0826429777, pages 198-200