Luxembourgish (/ˈlʌksəmbɜːrɡɪʃ/ LUK-səm-bur-ghish; also Luxemburgish,[2] Luxembourgian,[3] Letzebu(e)rgesch;[4] endonym: Lëtzebuergesch [ˈlətsəbuəjəʃ] ) is a West Germanic language that is spoken mainly in Luxembourg. About 300,000 people speak Luxembourgish worldwide.[5]

| Luxembourgish | |

|---|---|

| Lëtzebuergesch | |

| Pronunciation | [ˈlətsəbuəjəʃ] |

| Native to | Luxembourg; Saarland and north-west Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany; Arelerland and Saint-Vith district, Belgium; Moselle department, France |

| Region | Western Europe |

| Ethnicity | Luxembourgers |

Native speakers | 300,000 (2024)[1] |

Early forms | Proto-Indo-European

|

| Official status | |

Official language in | Luxembourg |

Recognised minority language in | Belgium (recognised by the French Community of Belgium) |

| Regulated by | Council for the Luxembourgish Language |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | lb |

| ISO 639-2 | ltz |

| ISO 639-3 | ltz |

| Glottolog | luxe1243 |

| Linguasphere | 52-ACB-db |

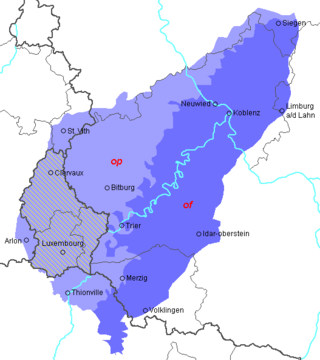

The area where Luxembourgish (pale indigo) and other dialects of Moselle Franconian (medium indigo) are spoken. The internal isogloss for words meaning "on, at", i.e. op and of, is also shown (Standard German: auf). | |

The language is standardized and officially the national language of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg. As such, Luxembourgish is different from the German language also used in the Grand Duchy. The German language exists in a national standard variety of Luxembourg, which is slightly different from the standard varieties in Germany, Austria or Switzerland. Another important language of Luxembourg is French, which had a certain influence on both the national language, Luxembourgish, and the Luxembourg national variety of German. Luxembourgish, German and French are the three official languages (Amtssprachen) of Luxembourg.

As a standard form of the Moselle Franconian language, Luxembourgish has similarities with other High German dialects and the wider group of West Germanic languages. The status of Luxembourgish as the national language of Luxembourg and the existence there of a regulatory body[6] have removed Luxembourgish, at least in part, from the domain of Standard German, its traditional Dachsprache. It is also related to the Transylvanian Saxon dialect spoken by the Transylvanian Saxons in Transylvania, contemporary central Romania.

History

editLuxembourgish was considered a German dialect like many others until about World War II but then it underwent ausbau, creating its own standard form in vocabulary, grammar, and spelling and therefore is seen today as an independent language. Luxembourgish managed to gain linguistic autonomy against a vigorous One Standard German Axiom by being framed as an independent language with a name rather than as a national pluricentric standard variety of German.

As Luxembourgish has a maximum of some 285,000[7] native speakers, resources in the language like books, newspapers, magazines, television, internet etc. are limited. Since most Luxembourgers also speak Standard German and French, there is strong competition with these languages, which both have large language resources. Because of this, the use of Luxembourgish remains limited.

Language family

editLuxembourgish belongs to the West Central German group of the High German languages and is the primary example of a Moselle Franconian language. Furthermore, it is closely related to Transylvanian Saxon which has been spoken since the High Middle Ages by the Transylvanian Saxons in Transylvania, present-day central Romania.[8][9][10]

Speech

editLuxembourgish is considered the national language of Luxembourg and also one of the three administrative languages, alongside German and French.[11][12]

In Luxembourg, 77% of residents can speak Luxembourgish,[13] and it is the primary language of 48% of the population.[14] It is also spoken in the Arelerland region of Belgium (part of the Province of Luxembourg) and in small parts of Lorraine in France.

In the German Eifel and Hunsrück regions, similar local Moselle Franconian dialects of German are spoken. The language is also spoken by a few descendants of Luxembourg immigrants in the United States and Canada.

Other Moselle Franconian dialects are spoken by ethnic Germans long settled in Transylvania, Romania (Siebenbürgen).

Moselle Franconian dialects outside the Luxembourg state border tend to have far fewer French loanwords, and these mostly remain from the French Revolution.

The political party that places the greatest importance on promoting, using and preserving Luxembourgish is the Alternative Democratic Reform Party (ADR) and its electoral success in the 1999 election pushed the CSV-DP government to make knowledge of it a criterion for naturalisation.[15][16] It is currently also the only political party in Luxembourg that wishes to implement written laws also in Luxembourgish and that wants Luxembourgish to be an officially recognized language of the European Union.[17][18] In this context, in 2005, then-Deputy Prime Minister Jean Asselborn of the LSAP rejected a demand made by the ADR to make Luxembourgish an official language of the EU, citing financial reasons and the sufficiency of official German and French.[19] A similar proposal by the ADR was rejected by the Chamber of Deputies in 2024.[20]

Varieties

editThere are several distinct dialect forms of Luxembourgish including Areler (from Arlon), Eechternoacher (Echternach), Dikrecher (Diekirch), Kliärrwer (Clervaux), Miseler (Moselle), Stater (Luxembourg), Veiner (Vianden), Minetter (Southern Luxembourg) and Weelzer (Wiltz). Further small vocabulary differences may be seen even between small villages.

Increasing mobility of the population and the dissemination of the language through mass media such as radio and television are leading to a gradual standardisation towards a "Standard Luxembourgish" through the process of koineization.[21]

Surrounding languages

editThere is no distinct geographic boundary between the use of Luxembourgish and the use of other closely related High German dialects (for example, Lorraine Franconian); it instead forms a dialect continuum of gradual change.

Spoken Luxembourgish is relatively hard to understand for speakers of German who are generally not familiar with Moselle Franconian dialects (or at least other West Central German dialects). They can usually read the language to some degree. For those Germans familiar with Moselle Franconian dialects, it is relatively easy to understand and speak Luxembourgish as far as the everyday vocabulary is concerned.[21] The large number of French loanwords in Luxembourgish may hamper communication about certain topics or with certain speakers (those who use many terms taken from French).

Writing

editStandardisation

editA number of proposals for standardising the orthography of Luxembourgish can be documented, going back to the middle of the 19th century. There was no officially recognised system until the adoption of the "OLO" (ofizjel lezebuurjer ortografi) on 5 June 1946.[22] This orthography provided a system for speakers of all varieties of Luxembourgish to transcribe words the way they pronounced them, rather than imposing a single, standard spelling for the words of the language. The rules explicitly rejected certain elements of German orthography (e.g., the use of ⟨ä⟩ and ⟨ö⟩,[23] the capitalisation of nouns). Similarly, new principles were adopted for the spelling of French loanwords.

- fiireje, rééjelen, shwèzt, veinejer (cf. German vorigen, Regeln, schwätzt, weniger)

- bültê, âprê, Shaarel, ssistém (cf. French bulletin, emprunt, Charles, système)

This proposed orthography, so different from existing "foreign" standards that people were already familiar with, did not enjoy widespread approval.

A more successful standard eventually emerged from the work of the committee of specialists charged with the task of creating the Luxemburger Wörterbuch, published in 5 volumes between 1950 and 1977. The orthographic conventions adopted in this decades-long project, set out in Bruch (1955), provided the basis of the standard orthography that became official on 10 October 1975.[24] Modifications to this standard were proposed by the Permanent Council of the Luxembourguish language and adopted officially in the spelling reform of 30 July 1999.[25] A detailed explanation of current practice for Luxembourgish can be found in Schanen & Lulling (2003).

Alphabet

editThe Luxembourgish alphabet consists of the 26 Latin letters plus three letters with diacritics: ⟨é⟩, ⟨ä⟩, and ⟨ë⟩. In loanwords from French and Standard German, other diacritics are usually preserved:

- French: Boîte, Enquête, Piqûre, etc.

- German: blöd, Bühn (from German Bühne), etc.

In German loanwords, the digraphs ⟨eu⟩ and ⟨äu⟩ indicate the diphthong /oɪ/, which does not appear in native words.

Orthography of vowels

edit

|

Eifeler Regel

editLike many other varieties of Western High German, Luxembourgish has a rule of final n-deletion in certain contexts. The effects of this rule (known as the "Eifel Rule") are indicated in writing, and therefore must be taken into account when spelling words and morphemes ending in ⟨n⟩ or ⟨nn⟩. For example:

- wann ech ginn "when I go", but wa mer ginn "when we go"

- fënnefandrësseg "thirty-five", but fënnefavéierzeg "forty-five".

Phonology

editConsonants

editThe consonant inventory of Luxembourgish is quite similar to that of Standard German.[26]

| Labial | Alveolar | Postalveolar | Dorsal | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ŋ | |||

| Plosive | fortis | p | t | k | ||

| lenis | b | d | ɡ | |||

| Affricate | voiceless | (p͡f) | t͡s | t͡ʃ | ||

| voiced | (d͡z) | (d͡ʒ) | ||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s | ʃ | χ | h |

| voiced | v | z | ʒ | ʁ | ||

| Trill | ʀ | |||||

| Approximant | l | j | ||||

- /p͡f/ occurs only in loanwords from Standard German.[27] Just as for many native speakers of Standard German, it tends to be simplified to [f] word-initially. For example, Pflicht ('obligation') is realised as [fliɕt] or, in careful speech, [p͡fliɕt].

- /v/ is realised as [w] when it occurs after /k, t͡s, ʃ/, e.g. zwee [t͡sweː] ('two').[28]

- /d͡z/ appears only in a few words, such as spadséieren /ʃpɑˈd͡zəɪ̯eʀen/ ('to go for a walk').[27]

- /d͡ʒ/ occurs only in loanwords from English.[27]

- /χ, ʁ/ have two types of allophones: alveolo-palatal [ɕ, ʑ] and uvular [χ, ʁ]. The latter occur before back vowels, and the former occur in all other positions.[29]

- Younger speakers tend to vocalize a word-final /ʀ/ to [ɐ].[29]

Vowels

edit| Front | Back | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| unrounded | rounded | |||||

| short | long | short | long | short | long | |

| Close | i | iː | (y) | (yː) | u | uː |

| Close-mid | e | eː | (øː) | o | oː | |

| Open-mid | (œ) | (œː) | ||||

| Open | æ | aː | ɑ | |||

- The front rounded vowels /y, yː, øː, œ, œː/ appear only in loanwords from French and Standard German. In loanwords from French, nasal /õː, ɛ̃ː, ɑ̃ː/ also occur. [27]

- /e/ has two allophones:

- Phonetically, the long mid vowels /eː, oː/ are raised close-mid (near-close) [e̝ː, o̝ː] and may even overlap with /iː, uː/.[31]

- /aː/ is the long variant of /ɑ/, not /æ/, which does not have a long counterpart.

| Ending point | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Front | Central | Back | |

| Close | iə uə | ||

| Mid | əɪ (oɪ) | əʊ | |

| Open | æːɪ ɑɪ | æːʊ ɑʊ | |

- /oɪ/ appears only in loanwords from Standard German.[27]

- The first elements of /æːɪ, æːʊ/ may be phonetically short [æ] in fast speech or in unstressed syllables.[33]

- The /æːɪ–ɑɪ/ and /æːʊ–ɑʊ/ contrasts arose from the former lexical tone contrast; the shorter /ɑɪ, ɑʊ/ were used in words with Accent 1, and the lengthened /æːɪ, æːʊ/ were used in words with Accent 2.[34]

Grammar

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2023) |

Nominal syntax

editLuxembourgish has three genders (masculine, feminine, and neuter), and three cases (nominative, accusative, and dative). These are marked morphologically on determiners and pronouns. As in German, there is no morphological gender distinction in the plural.

The forms of the articles and of some selected determiners are given below:

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

As seen above, Luxembourgish has plural forms of en ("a, an"), namely eng in the nominative/accusative and engen in the dative. They are not used as indefinite articles, which—as in German and English—do not exist in the plural, but they do occur in the compound pronouns wéi en ("what, which") and sou en ("such"). For example: wéi eng Saachen ("what things"); sou eng Saachen ("such things"). Moreover, they are used before numbers to express an estimation: eng 30.000 Spectateuren ("some 30,000 spectators").

Distinct nominative forms survive in a few nominal phrases such as der Däiwel ("the devil") and eiser Herrgott ("our Lord"). Rare examples of the genitive are also found: Enn des Mounts ("end of the month"), Ufanks der Woch ("at the beginning of the week"). The functions of the genitive are normally expressed using a combination of the dative and a possessive determiner: e.g. dem Mann säi Buch (lit. "to the man his book", i.e. "the man's book"). This is known as a periphrastic genitive, and is a phenomenon also commonly seen in dialectal and colloquial German, and in Dutch.

The forms of the personal pronouns are given in the following table (unstressed forms appear in parentheses):

| nominative | accusative | dative | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1sg | ech | mech | mir (mer) |

| 2sg | du (de) | dech | dir (der) |

| 3sgm | hien (en) | him (em) | |

| 3sgn | hatt (et) | ||

| 3sgf | si (se) | hir (er) | |

| 1pl | mir (mer) | äis / eis | |

| 2pl | dir (der) | iech | |

| 3pl | si (se) | hinnen (en) | |

The 2pl form is also used as a polite singular (like French vous, see T-V distinction); the forms are capitalised in writing:

- Wéi hues 'du' de Concert fonnt? ("How did you [informal sg.] like the concert?")

- Wéi hutt dir de Concert fonnt? ("How did you [informal pl.] like the concert?")

- Wéi hutt Dir de Concert fonnt? ("How did you [formal sg. or pl.] like the concert?")

Like most varieties of colloquial German, but even more invariably, Luxembourgish uses definite articles with personal names. They are obligatory and not to be translated:

- De Serge ass an der Kichen. ("Serge is in the kitchen.")

A feature Luxembourgish shares with only some western dialects of German is that women and girls are most often referred to with forms of the neuter pronoun hatt:

- Dat ass d'Nathalie. Hatt ass midd, well et vill a sengem Gaart geschafft huet. ("That's Nathalie. She is tired because she has worked a lot in her garden.")

Adjectives

editAdjectives show a different morphological behaviour when used attributively and predicatively. In predicative use, e.g. when they occur with verbs like sinn ("to be"), adjectives receive no extra ending:

- De Mann ass grouss. (masculine, "The man is tall.")

- D'Fra ass grouss. (feminine, "The woman is tall.")

- D'Meedchen ass grouss. (neuter, "The girl is tall.")

- D'Kanner si grouss. (plural, "The children are tall.")

In attributive use, i.e. when placed before the noun they describe, they change their ending according to the grammatical gender, number and case of the noun:

- de grousse Mann (masculine)

- déi grouss Fra (feminine)

- dat grousst Meedchen (neuter)

- déi grouss Kanner (plural)

The definite article changes with the use of an attributive adjective: feminine d' goes to déi (or di), neuter d' goes to dat, and plural d' changes to déi.

The comparative in Luxembourgish is formed analytically, i.e. the adjective itself is not altered (compare the use of -er in German and English; tall → taller, klein → kleiner). Instead it is formed using the adverb méi: e.g. schéin → méi schéin

- Lëtzebuerg ass méi schéi wéi Esch. ("Luxembourg is prettier than Esch.")

The superlative involves a synthetic form consisting of the adjective and the suffix -st: e.g. schéin → schéinst (compare German schönst, English prettiest). Attributive modification requires the emphatic definite article and the inflected superlative adjective:

- dee schéinste Mann ("the most handsome man")

- déi schéinst Fra ("the prettiest woman")

Predicative modification uses either the same adjectival structure or the adverbial structure am+ -sten: e.g. schéin → am schéinsten:

- Lëtzebuerg ass dee schéinsten / deen allerschéinsten / am schéinsten. ("Luxembourg is the most beautiful (of all).")

Some common adjectives have exceptional comparative and superlative forms:

- gutt, besser, am beschten ("good, better, best")

- vill, méi, am meeschten ("much, more, most")

- wéineg, manner, am mannsten ("few, fewer, fewest")

Several other adjectives also have comparative forms, not commonly used as normal comparatives, but in special senses:

- al ("old") → eeler Leit ("elderly people"), but: méi al Leit ("older people, people older than X")

- fréi ("early") → de fréiere President ("the former president"), but: e méi fréien Termin ("an earlier appointment")

- laang ("long") → viru längerer Zäit ("some time ago"), but: eng méi laang Zäit ("a longer period of time")

Word order

editLuxembourgish exhibits "verb second" word order in clauses. More specifically, Luxembourgish is a V2-SOV language, like German and Dutch. In other words, we find the following finite clausal structures:

- the finite verb in second position in declarative clauses and wh-questions

- Ech kafen en Hutt. Muer kafen ech en Hutt. (lit. "I buy a hat. Tomorrow buy I a hat.)

- Wat kafen ech haut? (lit. "What buy I today?")

- the finite verb in first position in yes/no questions and finite imperatives

- Bass de midd? ("Are you tired?")

- Gëff mer deng Hand! ("Give me your hand!")

- the finite verb in final position in subordinate clauses

- Du weess, datt ech midd sinn. (lit. "You know, that I tired am.")

Non-finite verbs (infinitives and participles) generally appear in final position:

- compound past tenses

- Ech hunn en Hutt kaf. (lit. "I have a hat bought.")

- infinitival complements

- Du solls net esou vill Kaffi drénken. (lit. "You should not so much coffee drink.")

- infinitival clauses (e.g., used as imperatives)

- Nëmme Lëtzebuergesch schwätzen! (lit. "Only Luxembourgish speak!")

These rules interact so that in subordinate clauses, the finite verb and any non-finite verbs must all cluster at the end. Luxembourgish allows different word orders in these cases:

- Hie freet, ob ech komme kann. (cf. German Er fragt, ob ich kommen kann.) (lit. "He asks if I come can.")

- Hie freet, ob ech ka kommen. (cf. Dutch Hij vraagt of ik kan komen.) (lit. "He asks if I can come.")

This is also the case when two non-finite verb forms occur together:

- Ech hunn net kënne kommen. (cf. Dutch Ik heb niet kunnen komen.) (lit, "I have not be-able to-come")

- Ech hunn net komme kënnen. (cf. German Ich habe nicht kommen können.) (lit, "I have not to-come be-able")

Luxembourgish (like Dutch and German) allows prepositional phrases to appear after the verb cluster in subordinate clauses:

- alles, wat Der ëmmer wollt wëssen iwwer Lëtzebuerg

- (lit. "everything what you always wanted know about Luxembourg")

Vocabulary

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2023) |

Luxembourgish has borrowed many French words. For example, the word for a bus driver is Buschauffeur (as in Dutch and Swiss German), which would be Busfahrer in German and chauffeur de bus in French.

Some words are different from Standard German, but have equivalents in German dialects. An example is Gromperen (potatoes – German: Kartoffeln). Other words are exclusive to Luxembourgish.

Selected common phrases

editNote: Words spoken in sound clip do not reflect all words on this list.

| Dutch | Luxembourgish | Standard German | English |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ja. | Jo. | Ja. | Yes. |

| Nee(n). | Nee(n). | Nein. | No. |

| Misschien, wellicht | Vläicht. | Vielleicht. | Maybe. |

| Hallo. (also moi in the north and east) | Moien. | Hallo. (also Moin in the north) | Hello. |

| Goedemorgen. | Gudde Moien. | Guten Morgen. | Good morning. |

| Goedendag. or Goedemiddag. | Gudde Mëtteg. | Guten Tag. | Good afternoon. |

| Goedenavond. | Gudden Owend. | Guten Abend. | Good evening. |

| Tot ziens. | Äddi. | Auf Wiedersehen. | Goodbye. |

| Dank u or Merci. (Belgium) | Merci. | Danke. | Thank you. |

| Waarom? or Waarvoor? | Firwat? | Warum? or Wofür? | Why, What for |

| Ik weet het niet. | Ech weess net. | Ich weiß nicht. | I don't know. |

| Ik versta het niet. | Ech verstinn net. | Ich verstehe nicht. | I don't understand. |

| Excuseer mij or Wablief? (Belgium) | Watgelift? or Entschëllegt? | Entschuldigung? | Excuse me? |

| Slagerszoon. | Metzleschjong. | Metzgersohn. / Metzgerjunge. | Butcher's son. |

| Spreek je Duits/Frans/Engels? | Schwätzt dir Däitsch/Franséisch/Englesch? | Sprichst du Deutsch/Französisch/Englisch? | Do you speak German/French/English? |

| Hoe heet je? | Wéi heeschs du? | Wie heißt du? | What is your name? |

| Hoe gaat het? | Wéi geet et? | Wie geht's? | How are you?, How is it going? |

| Politiek Fatsoen. | Politeschen Anstand. | Politischer Anstand. | Political decency |

| Zo. | Sou. | So. | So. |

| Vrij. | Fräi. | Frei. | Free. |

| Thuis. | Heem. | zu Hause. / Heim. | Home. |

| Ik. | Ech. | Ich. | I. |

| En. | An. | Und. | And. |

| Mijn. | Mäin. | Mein. | My. |

| Ezel. | Iesel. | Esel. | donkey, ass. |

| Met. | Mat. | Mit. | With. |

| Kind. | Kand. | Kind. | Child, kid |

| Weg. | Wee. | Weg. | Way. |

| Aardappel. | Gromper. | Kartoffel/Erdapfel. | Potato. |

| Brood. | Brout. | Brot. | Bread. |

Neologisms

editNeologisms in Luxembourgish include both entirely new words, and the attachment of new meanings to old words in everyday speech. The most recent neologisms come from the English language in the fields of telecommunications, computer science, and the Internet.

Recent neologisms in Luxembourgish include:[35]

- direct loans from English: Browser, Spam, CD, Fitness, Come-back, Terminal, Hip, Cool, Tip-top

- also found in German: Sichmaschinn (search engine, German: Suchmaschine), schwaarzt Lach (black hole, German: Schwarzes Loch), Handy (mobile phone), Websäit (webpage, German: Webseite)

- native Luxembourgish

- déck as an emphatic like ganz and voll, e.g. Dëse Kuch ass déck gutt! ("This cake is really good!")

- recent expressions, used mainly by teenagers: oh mëllen! ("oh crazy"), en décke gelénkt ("you've been tricked") or cassé (French for "(you've been) owned")

Academic projects

editBetween 2000 and 2002, Luxembourgish linguist Jérôme Lulling compiled a lexical database of 125,000-word forms as the basis for the first Luxembourgish spellchecker (Projet C.ORT.IN.A).[36]

The LaF (Lëtzebuergesch als Friemsprooch – Luxembourgish as a Foreign Language) is a set of four language proficiency certifications for Luxembourgish and follows the ALTE framework of language examination standards. The tests are administered by the Institut National des Langues Luxembourg.[37]

The "Centre for Luxembourg Studies" at the University of Sheffield was founded in 1995 on the initiative of Professor Gerald Newton. It is supported by the government of Luxembourg which funds an endowed chair in Luxembourg Studies at the university.[38] The first class of students to study the language outside of the country as undergraduate students began their studies at the 'Centre for Luxembourg Studies' at Sheffield in the academic year 2011–2012.

Endangered status claims

editUNESCO declared Luxembourgish to be an endangered language in 2019, adding it to its Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger.[39][40]

Additionally, some local media[citation needed] have argued that the Luxembourgish language is at risk of disappearing, and that it should be considered an endangered language.[41] Even though the government claims that more people than ever are able to speak Luxembourgish, these are absolute numbers and often include the many naturalized citizens who have passed the Sproochentest, a language test that certifies the knowledge of merely A.2. in speaking and B.1. in understanding.[42]

Luxembourgish language expert and historian Alain Atten argues that not only the absolute number of Luxembourgish speakers should be considered when defining the status of a language, but also the proportion of speakers in a country. Noting that the proportion of native Luxembourgish speakers has decreased in recent decades, Atten believes that Luxembourgish will inevitably disappear, stating:

"It is simple math, if there are about 70% foreigners and about 30% Luxembourgers (which is the case in Luxembourg City), then it cannot possibly be said that Luxembourgish is thriving. That would be very improbable."[43]

Alain Atten also argues that the situation is even more dramatic, since the cited percentages take only the residents of Luxembourg into account, excluding the 200,000 cross-border-workers present in the country on a daily basis.[43] This group plays a major role in the daily use of languages in Luxembourg, thus further lowering the percentage of Luxembourgish speakers present in the country.

The following numbers are based on statistics by STATEC (those since 2011) and show that the percentage of the population that is able to speak Luxembourgish has been constantly diminishing for years (The 200,000 cross-border workers are not included in this statistic):[43]

| Year | Percentage |

|---|---|

| 1846 | 99.0% [citation needed] |

| 1900 | 88.0% |

| 1983 | 80.6% |

| 2011 | 70.51% |

| 2012 | 70.07% |

| 2013 | 69.65% |

| 2014 | 69.17% |

| 2015 | 68.78% |

| 2016 | 68.35% |

| 2017 | 67.77% |

It has also been argued[citation needed] that two very similar languages, Alsatian and Lorraine Franconian, which were very broadly spoken by the local populations at the beginning of the 20th century in Alsace and in Lorraine respectively, have been nearly completely supplanted by French, and that a similar fate could also be possible for Luxembourgish.[44][45] Another example of the replacement of Luxembourgish by French occurred in Arelerland (historically a part of Luxembourg, today in Belgium), where the vast majority of the local population spoke Luxembourgish as a native language well into the 20th century. Today, Luxembourgish is nearly extinct in this region, having been replaced by French.

According to some Luxembourgish news media[citation needed] and members of Actioun Lëtzebuergesch (an association for the preservation and promotion of the language), the biggest threat to the existence of Luxembourgish is indeed French, since it is the language of most official documents and street signs in Luxembourg; this considerably weakens the possibility for Luxembourgish to be practiced by new speakers and learners.[46] In most cases, this passively forces expats to learn French instead of Luxembourgish.[46]

In 2021 it was announced that public announcements in Luxembourgish (and in German as well) at Luxembourg Airport would cease; it would only be using French and English for future public announcements.[47] This will cause Luxembourgish to go unused at Luxembourg Airport after many decades. Actioun Lëtzebuergesch declared itself to be hugely upset by this new governmental measure, citing that other airports in the world seem to have no problems making public announcements in multiple languages.[48] According to a poll conducted by AL, 92.84% of the Luxembourgish population wished to have public announcements to be made in Luxembourgish at Luxembourg Airport.[48]

ADR politician Fred Keup has claimed that Luxembourgish is already on its way to complete replacement by French.[49]

See also

editNotes and references

editNotes

edit- ^ The letter ⟨é⟩ today represents the same sound as ⟨ë⟩ before ⟨ch⟩. The ostensibly inconsistent spelling ⟨é⟩ is based on the traditional, now widely obsolete pronunciation of the sound represented by ⟨ch⟩ as a palatal [ç]. As this consonant is pronounced further back in the mouth, it triggered the use of the front allophone of /e/ (that is [e]) as is the case before the velars (/k, ŋ/). Since the more forward alveolo-palatal [ɕ] has replaced the palatal [ç] for almost all speakers, the allophone [ə] is used as before any non-velar consonant. So the word mécht ('[he] makes'), which is now pronounced [məɕt], used to be pronounced [meçt]; this is the reason for the spelling. The spelling ⟨mëcht⟩, which reflects the contemporary pronunciation, is not standard.

- ^ In the standard orthography, /ɑʊ̯/ and /æːʊ̯/ are not distinguished.

References

edit- ^ Luxembourgish at Ethnologue (25th ed., 2022)

- ^ "Luxemburgish – definition of Luxemburgish in English from the Oxford dictionary". Archived from the original on 7 July 2012. Retrieved 21 March 2015.

- ^

- Kas Deprez (1997). Michael G. Clyne (ed.). "Diets, Nederlands, Nederduits, Hollands, Vlaams, Belgisch-Nederlands". Undoing and Redoing Corpus Planning. Walter de Gruyter: 249. ISBN 9783110155099.

- Bengt Skoog (1983). Immigrants and Cultural Development in European Towns. Council for Cultural Co-operation. p. 51. ISBN 9789287102393.

- National Geographic Society (2005). Our Country's Regions: Outline maps. Macmillan/McGraw-Hill. p. 59. ISBN 9780021496259.

- ^ "Letzeburgesch – definition of Lëtzeburgesch in English from the Oxford dictionary". Archived from the original on 15 September 2012. Retrieved 21 March 2015.

- ^ "Le nombre de locuteurs du luxembourgeois revu à la hausse" (PDF). Retrieved 8 November 2012.

- ^ "Law establishing the Conseil Permanent de la Langue Luxembourgeoise (CPLL)" (PDF).

- ^ Fehlen, Fernand. "Luxemburgs Sprachenmarkt im Wandel" (PDF). uni.lu.

- ^ Vu(m) Nathalie Lodhi (13 January 2020). "The Transylvanian Saxon dialect, a not-so-distant cousin of Luxembourgish". RTL. Retrieved 18 September 2022.

- ^ Stephen McGrath (10 September 2019). "The Saxons first arrived in Romania's Transylvania region in the 12th Century, but over the past few decades the community has all but vanished from the region". BBC Travel. Retrieved 18 September 2022.

- ^ Victor Rouă (19 August 2015). "A Brief History Of The Transylvanian Saxon Dialect". The Dockyards. Retrieved 16 January 2023.

- ^ "Mémorial A no. 16 (27 February 1984), pp. 196–7: "Loi du 24 février 1984 sur le régime des langues"". Archived from the original on 3 February 2006. Retrieved 15 September 2006.

- ^ Hausemer, Georges. Luxemburger Lexikon - Das Großherzogtum von A-Z.

- ^ "What languages do people speak in Luxembourg?". luxembourg.public.lu. Retrieved 28 September 2021.

- ^ "Une diversité linguistique en forte hausse" (PDF). statistiques.public.lu (in French). Retrieved 15 February 2024.

- ^ Moyse, François; Brasseur, Pierre; Scuto, Denis (2004). "Luxembourg". In Bauböck, Rainer; Ersbøll, Eva; Groenendijk, Kees; Waldrauch, Harald (eds.). Acquisition and Loss of Nationality: Policies and Trends in 15 European States – Volume 2: Country Analysis. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. p. 380. ISBN 978-90-5356-921-4.

- ^ "VIDEO: ADR-Kongress: Déi 3 Haaptpilieren: Wuesstem, Lëtzebuerger Sprooch a Famill".

- ^ "Lëtzebuerger Sprooch stäerken: ADR: Wichteg Gesetzer och op Lëtzebuergesch".

- ^ "26. Lëtzebuergesch, DÉI Sprooch fir eist Land!". Archived from the original on 23 October 2021. Retrieved 13 October 2021.

- ^ "De l'usage de la langue luxembourgeoise dans le contexte européen : Une question parlementaire de Fernand Kartheiser - Europaforum Luxembourg - Septembre 2010".

- ^ "Reconnaissance de la langue luxembourgeoise en tant que langue officielle de l'Union européenne au même titre que la langue irlandaise". chd.lu (in French). 30 January 2024.

- ^ a b Ammon, Ulrich - Die Stellung der deutschen Sprache in der Welt (de Gruyter Mouton); ISBN 978-3-11-019298-8

- ^ "Mémorial A no. 40 (7 September 1946), pp. 637–41: "Arrêté ministériel du 5 juin 1946 portant fixation d'un système officiel d'orthographe luxembourgeois"". Archived from the original on 26 April 2005. Retrieved 15 September 2006.

- ^ "Et get kèèn ä geshriven. [...] Et get kèèn ö geshriven." (p. 639)

- ^ Mémorial B no. 68 (16 November 1976), pp. 1365–90: "Arrêté ministériel du 10 octobre 1975 portant réforme du système officiel d'orthographe luxembourgeoise".

- ^ "Mémorial A no. 112 (11 August 1999), pp. 2040–8: "Règlement grand-ducal du 30 juillet 1999 portant réforme du système officiel d'orthographe luxembourgeoise"". Archived from the original on 3 November 2005. Retrieved 15 September 2006.

- ^ a b Gilles & Trouvain (2013), p. 67.

- ^ a b c d e Gilles & Trouvain (2013), p. 72.

- ^ Gilles & Trouvain (2013), p. 69.

- ^ a b Gilles & Trouvain (2013), p. 68.

- ^ Gilles & Trouvain (2013), pp. 68–69.

- ^ a b c d e f Gilles & Trouvain (2013), p. 70.

- ^ Trouvain & Gilles (2009), p. 75.

- ^ a b Gilles & Trouvain (2013), p. 71.

- ^ Trouvain & Gilles (2009), p. 72.

- ^ Lulling, Jérôme. (2002) La créativité lexicale en luxembourgeois, Doctoral thesis, Université Paul Valéry Montpellier III

- ^ "Eurogermanistik - Band 20". 27 September 2007. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 26 July 2021.

- ^ "Institut national des langues – INL – Passer un examen à l'INL". Archived from the original on 8 May 2015.

- ^ "Centre for Luxembourg Studies". Retrieved 11 September 2011.

- ^ ""Endangered" but growing: The Luxemburgish language celebrates 35th anniversary".

- ^ "Is Luxembourgish an endangered language?". 11 December 2017.

- ^ "Lëtzebuergesch gëtt ëmmer méi aus dem Alldag verdrängt". MOIEN.LU (in Luxembourgish). 25 February 2021. Archived from the original on 16 October 2021. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- ^ "Examen d'évaluation de la langue luxembourgeoise " Sproochentest " | Institut National des Langues" (in French). Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- ^ a b c "Lëtzebuergesch gëtt ëmmer méi aus dem Alldag verdrängt". MOIEN.LU (in Luxembourgish). 25 February 2021. Archived from the original on 16 October 2021. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- ^ Babbel.com; GmbH, Lesson Nine. "Welche Sprachen werden in Elsass-Lothringen gesprochen?". Das Babbel Magazin (in German). Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- ^ "D'Lëtzebuergescht, bald eng langue morte?!". Guy Kaiser Online. 12 August 2020. Retrieved 16 October 2021.

- ^ a b "D'Lëtzebuergescht, bald eng langue morte?!". Guy Kaiser Online. 12 August 2020. Retrieved 16 October 2021.

- ^ "Findel airport: Public announcements no longer available in Luxembourgish". today.rtl.lu. Retrieved 13 October 2021.

- ^ a b "D'Sprooche vun den automateschen Ukënnegungen um Flughafe Findel" (PDF). www.actioun-letzebuergesch.lu (in Luxembourgish). 7 September 2021. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- ^ "Invité vun der Redaktioun (30. Mee) - Fred Keup: "D'ADR ass wichteg fir de politeschen Debat"".

Bibliography

edit- Bruch, Robert. (1955) Précis de grammaire luxembourgeoise. Bulletin Linguistique et Ethnologique de l'Institut Grand-Ducal, Luxembourg, Linden. (2nd edition of 1968)

- Gilles, Peter; Trouvain, Jürgen (2013), "Luxembourgish" (PDF), Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 43 (1): 67–74, doi:10.1017/S0025100312000278

- Schanen, François and Lulling, Jérôme. (2003) Introduction à l'orthographe luxembourgeoise. (text available in French and Luxembourgish)

- Trouvain, Jūrgen; Gilles, Peter (2009). PhonLaF – phonetic online material for Luxembourgish as a foreign language (PDF). Phonetics Teaching & Learning Conference.

Further reading

editIn English

- NEWTON, Gerald (ed.), Luxembourg and Lëtzebuergesch: Language and Communication at the Crossroads of Europe, Oxford, 1996, ISBN 0-19-824016-3

- Tamura, Kenichi (2011), "The Wiltz Dialect in a Luxembourgish Drama for Children: Analysis of the Script for "Den Zauberer vun Oz" (2005)" (PDF), Bulletin of Aichi University of Education, 60: 11–21, archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016

In French

- BRAUN, Josy, et al. (en coll. avec Projet Moien), Grammaire de la langue luxembourgeoise. Luxembourg, Ministère de l'Éducation nationale et de la Formation professionnelle 2005. ISBN 2-495-00025-8

- SCHANEN, François, Parlons Luxembourgeois, Langue et culture linguistique d'un petit pays au coeur de l'Europe. Paris, L'Harmattan 2004, ISBN 2-7475-6289-1

- SCHANEN, François / ZIMMER, Jacqui, 1,2,3 Lëtzebuergesch Grammaire. Band 1: Le groupe verbal. Band 2: Le groupe nominal. Band 3:L'orthographe. Esch-sur-Alzette, éditions Schortgen, 2005 et 2006

- SCHANEN, François / ZIMMER, Jacqui, Lëtzebuergesch Grammaire luxembourgeoise. En un volume. Esch-sur-Alzette, éditions Schortgen, 2012. ISBN 978-2-87953-146-5

In Luxembourgish

- SCHANEN, François, Lëtzebuergesch Sproocherubriken. Esch-sur-Alzette, éditions Schortgen, 2013.ISBN 978-2-87953-174-8

- Meyer, Antoine, E' Schrek ob de' lezeburger Parnassus, Lezeburg (Luxembourg), Lamort, 1829

In German

- BRUCH, Robert, Grundlegung einer Geschichte des Luxemburgischen, Luxembourg, Publications scientifiques et littéraires du Ministère de l'Éducation nationale, 1953, vol. I; Das Luxemburgische im westfränkischen Kreis, Luxembourg, Publications scientifiques et littéraires du Ministère de l'Éducation nationale, 1954, vol. II

- MOULIN, Claudine and Nübling, Damaris (publisher): Perspektiven einer linguistischen Luxemburgistik. Studien zu Diachronie und Synchronie., Universitätsverlag Winter, Heidelberg, 2006. This book has been published with the support of the Fonds National de la Recherche

- GILLES, Peter (1998). "Die Emanzipation des Lëtzebuergeschen aus dem Gefüge der deutschen Mundarten". Zeitschrift für deutsche Philologie. 117: 20–35.

- BERG, Guy, Mir wëlle bleiwe wat mir sin: Soziolinguistische und sprachtypologische Betrachtungen zur luxemburgischen Mehrsprachigkeit., Tübingen, 1993 (Reihe Germanistische Linguistik 140). ISBN 3-484-31140-1

- (phrasebook) REMUS, Joscha, Lëtzebuergesch Wort für Wort. Kauderwelsch Band 104. Bielefeld, Reise Know-How Verlag 1997. ISBN 3-89416-310-0

- WELSCHBILLIG Myriam, SCHANEN François, Jérôme Lulling, Luxdico Deutsch: Luxemburgisch ↔ Deutsches Wörterbuch, Luxemburg (Éditions Schortgen) 2008, Luxdico Deutsch

External links

edit- Conseil Permanent de la Langue Luxembourgeoise

- LuxVocabulary: Web application for learning Luxembourgish vocabulary

- Spellcheckers and dictionaries

- Spellcheckers for Luxembourgish: Spellchecker.lu, Spellchecker.lu - Richteg Lëtzebuergesch schreiwen

- Luxdico online dictionary (24.000 words)

- Lëtzebuerger Online Dictionnaire (Luxembourgish Online Dictionary) with German, French and Portuguese translations created by the CPLL

- dico.lu – Dictionnaire Luxembourgeois//Français

- Luxembourgish Dictionary with pronunciation, translation to and from English, French, German, Portuguese, Spanish, Italian

- Luxogramm – Information system for the Luxembourgish grammar (University of Luxembourg, LU)