The Geography Markup Language (GML) is the XML grammar defined by the Open Geospatial Consortium (OGC) to express geographical features. GML serves as a modeling language for geographic systems as well as an open interchange format for geographic transactions on the Internet. Key to GML's utility is its ability to integrate all forms of geographic information, including not only conventional "vector" or discrete objects, but coverages (see also GMLJP2) and sensor data.

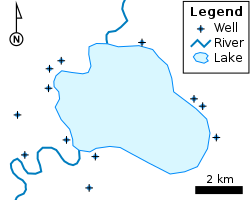

A vector map, with points, polylines and polygons. | |

| Filename extension | .gml or .xml |

|---|---|

| Internet media type |

application/gml+xml[1] |

| Developed by | Open Geospatial Consortium |

| Initial release | 2000 |

| Latest release | 3.2.1[2] 27 August 2007 |

| Type of format | Geographic Information System |

| Extended from | XML |

| Standard | ISO 19136:2007 |

GML model

editGML contains a rich set of primitives which are used to build application specific schemas or application languages. These primitives include:

- Feature

- Geometry

- Coordinate reference system

- Topology

- Time

- Dynamic feature

- Coverage (including geographic images)

- Unit of measure

- Directions

- Observations

- Map presentation styling rules

The original GML model was based on the World Wide Web Consortium's Resource Description Framework (RDF). Subsequently, the OGC introduced XML schemas into GML's structure to help connect the various existing geographic databases, whose relational structure XML schemas more easily defined. The resulting XML-schema-based GML retains many features of RDF, including the idea of child elements as properties of the parent object (RDFS) and the use of remote property references.

Profile

editGML profiles are logical restrictions to GML, and may be expressed by a document, an XML schema or both. These profiles are intended to simplify adoption of GML, to facilitate rapid adoption of the standard. The following profiles, as defined by the GML specification, have been published or proposed for public use:

- A Point Profile for applications with point geometric data but without the need for the full GML grammar;

- A GML Simple Features profile supporting vector feature requests and transactions, e.g. with a WFS;

- A GML profile for GMLJP2 (GML in JPEG 2000);

- A GML profile for RSS.

Profiles are distinct from application schemas. Profiles are part of GML namespaces (Open GIS GML) and define restricted subsets of GML. Application schemas are XML vocabularies defined using GML and which live in an application-defined target namespace. Application schemas can be built on specific GML profiles or use the full GML schema set.

Profiles are often created in support for GML derived languages (see application schemas) created in support of particular application domains such as commercial aviation, nautical charting or resource exploitation.

The GML Specification (Since GML v3.) contains a pair of XSLT scripts (usually referred to as the "subset tool") that can be used to construct GML profiles.

GML Simple Features Profile

editThe GML Simple Features Profile is a more complete profile of GML than the above Point Profile and supports a wide range of vector feature objects, including the following:

- A reduced geometry model allowing 0d, 1d and 2d linear geometric objects (all based on linear interpolation) and the corresponding aggregate geometries (gml:MultiPoint, gml:MultiCurve, etc.).

- A simplified feature model which can only be one level deep (in the general GML model, arbitrary nesting of features and feature properties is not permitted).

- All non-geometric properties must be XML Schema simple types – i.e. cannot contain nested elements.

- Remote property value references (xlink:href) just like in the main GML specification.

Since the profile aims to provide a simple entry point, it does not provide support for the following:

- coverages

- topology

- observations

- value objects (for real time sensor data)

- dynamic features

Nonetheless it supports a good variety of real world problems.

Subset tool

editIn addition, the GML specification provides a subset tool to generate GML profiles containing a user-specified list of components. The tool consists of three XSLT scripts. The scripts generate a profile that a developer may extend manually or otherwise enhance through schema restriction. As restrictions of the full GML specification, application schemas that a profile can generate must themselves be valid GML application schemas.

The subset tool can generate profiles for many other reasons as well. Listing the elements and attributes to include in the resultant profile schema and running the tool results in a single profile schema file containing only the user-specified items and all of the element, attribute and type declarations on which the specified items depend. Some Profile schemas created in this manner support other specifications including IHO S-57 and GML in JPEG 2000.

Application schema

editIn order to expose an application's geographic data with GML, a community or organization creates an XML schema specific to the application domain of interest (the application schema). This schema describes the object types whose data the community is interested in and which community applications must expose. For example, an application for tourism may define object types including monuments, places of interest, museums, road exits, and viewpoints in its application schema. Those object types in turn reference the primitive object types defined in the GML standard.

Some other markup languages for geography use schema constructs, but GML builds on the existing XML schema model instead of creating a new schema language. Application schemas are normally designed using ISO 19103 (Geographic information – Conceptual schema language)[3] conformant UML, and then the GML Application created by following the rules given in Annex E of ISO 19136.

List of public GML Application Schemas

editFollowing is a list of known, publicly accessible GML Application Schemas:

- AIXM Aeronautical Information eXchange Model ( see http://aixm.aero – Commercial Aviation Related Schema)

- CAAML – Canadian Avalanche Association Markup Language

- CityGML – a common information model and GML application schema for virtual 3D city / regional models.[4]

- Coverages – an interoperable, encoding-neutral information model for the digital representation of spatio-temporally varying phenomena (such as sensor, image, model, and statistics data), based on the abstract model of ISO 19123

- Climate Science Modelling Language (CSML)[5]

- Darwin Core GML application schema. An implementation of the Darwin Core schema in GML for sharing biodiversity occurrence data.

- GeoSciML – from IUGS Commission for Geoscience Information

- GPML – the GPlates Markup Language, an information model and application schema for plate-tectonics[6]

- InfraGML - a GML implementation initiated 2012,[7] reflecting the then missing update of LandXML

- INSPIRE application schemas[8]

- IWXXM – Aviation weather GML application schema

- NcML/GML – NetCDF-GML[9]

- Observations and Measurements schema for observation metadata and results

- OS MasterMap GML[10]

- SensorML schema for describing instruments and processing chains

- SoTerML schema for describing Soil and Terrain data

- TigerGML – US Census[11]

- Water Quality Data Project Archived 2008-07-21 at the Wayback Machine from Dept. of Natural Resources, New South Wales

- WXXM – Weather Information Exchange Model

- IndoorGML – an OGC standard for an open data model and XML schema for indoor spatial information.

GML and KML

editKML, made popular by Google, complements GML. Whereas GML is a language to encode geographic content for any application, by describing a spectrum of application objects and their properties (e.g. bridges, roads, buoys, vehicles etc.), KML is a language for the visualization of geographic information tailored for Google Earth. KML can be used to render GML content, and GML content can be “styled” using KML for the purposes of presentation. KML is first and foremost a 3D portrayal transport, not a data exchange transport. As a result of this significant difference in purpose, encoding GML content for portrayal using KML results in significant and unrecoverable loss of structure and identity in the resulting KML. Over 90% of GML's structures (such as, to name a few, metadata, coordinate reference systems, horizontal and vertical datums, geometric integrity of circles, ellipses, arcs, etc.) cannot be transformed to KML without loss or non-standard encoding. Similarly, due to KML's design as a portrayal transport, encoding KML content in GML will result in significant loss of KML portrayal structures such as regions, level of detail rules, viewing and animation information, as well as styling information and multiscale representation. The ability to portray placemarks at multiple levels of details distinguishes KML from GML, since portrayal is outside the scope of GML.[12]

GML geometries

editGML encodes the GML geometries, or geometric characteristics, of geographic objects as elements within GML documents according to the "vector" model. The geometries of those objects may describe, for example, roads, rivers, and bridges.

The key GML geometry object types in GML 1.0 and GML 2.0, are the following:

- Point

- LineString

- Polygon

GML 3.0 and higher also includes structures to describe "coverage" information, the "raster" model, such as gathered via remote sensors and images, including most satellite data.

Features

editGML defines features distinct from geometry objects. A feature is an application object that represents a physical entity, e.g. a building, a river, or a person. A feature may or may not have geometric aspects. A geometry object defines a location or region instead of a physical entity, and hence is different from a feature.

In GML, a feature can have various geometry properties that describe geometric aspects or characteristics of the feature (e.g. the feature's Point or Extent properties). GML also provides the ability for features to share a geometry property with one another by using a remote property reference on the shared geometry property. Remote properties are a general feature of GML borrowed from RDF. An xlink:href attribute on a GML geometry property means that the value of the property is the resource referenced in the link.

For example, a Building feature in a particular GML application schema might have a position given by the primitive GML geometry object type Point. However, the Building is a separate entity from the Point that defines its position. In addition, a feature may have several geometry properties (or none at all), for example an extent and a position.

Coordinates

editCoordinates in GML represent the coordinates of geometry objects. Coordinates can be specified by any of the following GML elements:

<gml:coordinates>

<gml:pos>

<gml:posList>

GML has multiple ways to represent coordinates. For example, the <gml:coordinates> element can be used, as follows:

<gml:Point gml:id="p21" srsName="http://www.opengis.net/def/crs/EPSG/0/4326">

<gml:coordinates>45.67, 88.56</gml:coordinates>

</gml:Point>

When expressed as above, the individual coordinates (e.g. 88.56) are not separately accessible through the XML Document Object Model since the content of the <gml:coordinates> element is just a single string.

To make GML coordinates accessible through the XML DOM, GML 3.0 introduced the <gml:pos> and <gml:posList> elements. (Although GML versions 1 and 2 had the <gml:coord> element, it is treated as a defect and is not used.) Using the <gml:pos> element instead of the <gml:coordinates> element, the same point can be represented as follows:

<gml:Point gml:id="p21" srsName="http://www.opengis.net/def/crs/EPSG/0/4326">

<gml:pos srsDimension="2">45.67 88.56</gml:pos>

</gml:Point>

The coordinates of a <gml:LineString> geometry object can be represented with the <gml:coordinates> element:

<gml:LineString gml:id="p21" srsName="http://www.opengis.net/def/crs/EPSG/0/4326">

<gml:coordinates>45.67, 88.56 55.56,89.44</gml:coordinates>

</gml:LineString >

The <gml:posList> element is used to represent a list of coordinate tuples, as required for linear geometries:

<gml:LineString gml:id="p21" srsName="http://www.opengis.net/def/crs/EPSG/0/4326">

<gml:posList srsDimension="2">45.67 88.56 55.56 89.44</gml:posList>

</gml:LineString >

For GML data servers (WFS) and conversion tools that only support GML 1 or GML 2 (i.e. only the <gml:coordinates> element), there is no alternative to <gml:coordinates>. For GML 3 documents and later, however, <gml:pos> and <gml:posList> are preferable to <gml:coordinates>.

Coordinate reference system

editA coordinate reference system (CRS) determines the geometry of each geometry element in a GML document.

Unlike KML or GeoRSS, GML does not default to a coordinate system when none is provided. Instead, the desired coordinate system must be specified explicitly with a CRS. The elements whose coordinates are interpreted with respect to such a CRS include the following:

<gml:coordinates><gml:pos><gml:posList>

An srsName attribute attached to a geometry object specifies the object's CRS, as shown in the following example:

<gml:Point gml:id="p1" srsName="#srs36">

<gml:coordinates>100,200</gml:coordinates>

</gml:Point>

The value of the srsName attribute is a Uniform Resource Identifier (URI). It refers to a definition of the CRS that is used to interpret the coordinates in the geometry. The CRS definition may be in a document (i.e. a flat file) or in an online web service. Values of EPSG codes can be resolved by using the EPSG Geodetic Parameter Dataset registry operated by the Oil and Gas Producers Association at [1] Archived 2020-08-09 at the Wayback Machine.

The srsName URI may also be a Uniform Resource Name (URN) for referencing a common CRS definition. The OGC has developed a URN structure and a set specific URNs to encode some common CRS. A URN resolver resolves those URNs to GML CRS definitions.

Examples

editPolygons, Points, and LineString objects are encoded in GML 1.0 and 2.0 as follows:

<gml:Polygon>

<gml:outerBoundaryIs>

<gml:LinearRing>

<gml:coordinates>0,0 100,0 100,100 0,100 0,0</gml:coordinates>

</gml:LinearRing>

</gml:outerBoundaryIs>

</gml:Polygon>

<gml:Point>

<gml:coordinates>100,200</gml:coordinates>

</gml:Point>

<gml:LineString>

<gml:coordinates>100,200 150,300</gml:coordinates>

</gml:LineString>

LineString objects, along with LinearRing objects, assume linear interpolation between the specified points. Also the coordinates of a Polygon have to be closed.

Features using geometries

editThe following GML example illustrates the distinction between features and geometry objects. The Building feature has several geometry objects, sharing one of them (the Point with identifier p21) with the SurveyMonument feature:

<abc:Building gml:id="SearsTower">

<abc:height>52</abc:height>

<abc:position xlink:type="Simple" xlink:href="#p21"/>

</abc:Building>

<abc:SurveyMonument gml:id="g234">

<abc:position>

<gml:Point gml:id="p21">

<gml:posList>100,200</gml:posList>

</gml:Point>

</abc:position>

</abc:SurveyMonument>

The reference is to the shared Point and not to the SurveyMonument, since any feature object can have more than one geometry object property.

Point Profile

editThe GML Point Profile contains a single GML geometry, namely a <gml:Point> object type. Any XML Schema can use the Point Profile by importing it and referencing the subject <gml:Point> instance:

<PhotoCollection xmlns="http://www.myphotos.org" xmlns:gml="http://www.opengis.net/gml"

xmlns:xsi="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance"

xsi:schemaLocation="http://www.myphotos.org

MyGoodPhotos.xsd">

<items>

<Item>

<name>Lynn Valley</name>

<description>A shot of the falls from the suspension bridge</description>

<where>North Vancouver</where>

<position>

<gml:Point srsDimension="2" srsName="http://www.opengis.net/def/crs/EPSG/0/4326">

<gml:pos>49.40 -123.26</gml:pos>

</gml:Point>

</position>

</Item>

</items>

</PhotoCollection>

When using the Point Profile, the only geometry object is the '<gml:Point>' object. The rest of the geography is defined by the photo-collection schema.

History

editInitial work – to OGC recommendation paper

editRon Lake started work on GML in the fall of 1998, following earlier work on XML encodings for radio broadcasting. Lake presented his early ideas to an OGC meeting in Atlanta, Georgia, in February 1999, under the title xGML. This introduced the idea of a GeoDOM, and the notion of Geographic Styling Language (GSL) based on XSL. Akifumi Nakai of NTT Data also presented at the same meeting on work partly underway at NTT Data on an XML encoding called G-XML, which was targeted at location–based services.[13] In April 1999, Galdos created the XBed team (with CubeWerx, Oracle Corporation, MapInfo Corporation, NTT Data, Mitsubishi, and Compusult as subcontractors). Xbed was focused on the use of XML for geospatial. This led to the creation of SFXML (Simple Features XML) with input from Galdos, US Census, and NTT Data. Galdos demonstrated an early map style engine pulling data from an Oracle-based "GML" data server (precursor of the WFS) at the first OGC Web Map Test Bed in September 1999. In October 1999, Galdos Systems rewrote the SFXML draft document into a Request for Comment, and changed the name of the language to GML (Geography Markup Language). This document introduced several key ideas that became the foundation of GML, including the 1) Object-Property-Value rule, 2) Remote properties (via rdf:resource), and 3) the decision to use application schemas rather than a set of static schemas. The paper also proposed that the language be based on the Resource Description Framework (RDF) rather than on the DTDs used to that point. These issues, including the use of RDF, were hotly debated within the OGC community during 1999 and 2000, with the result that the final GML Recommendation Paper contained three GML profiles – two based on DTD, and one on RDF – with one of the DTD's using a static schema approach. This passed as a Recommendation Paper at the OGC in May 2000.[14]

Moving to XML Schema – Version 2.

editEven before the passage of the Recommendation Paper at the OGC, Galdos had started work on an XML Schema version of GML, replacing the rdf:resource scheme for remote references with the use of xlink:href, and developing specific patterns (e.g. Barbarians at the Gate) for handling extensions for complex structures like feature collections. Much of the XML Schema design work was done by Mr. Richard Martell of Galdos who served as the document editor and who was mainly responsible for the translation of the basic GML model into an XML Schema. Other important inputs in this time frame came from Simon Cox (CSIRO Australia), Paul Daisey (US Census), David Burggraf (Galdos), and Adrian Cuthbert (Laser-Scan). The US Army Corps of Engineers (particularly Jeff Harrison) were quite supportive of the development of GML. The US Army Corps of Engineers sponsored the “USL Pilot” project, which was very helpful in exploring the utility of linking and styling concepts in the GML specification, with important work being done by Monie (Ionic) and Xia Li (Galdos). The XML Schema specification draft was submitted by Galdos and was approved for public distribution in December 2000. It became a Recommendation Paper in February 2001 and an Adopted Specification in May of the same year. This version (V2.0) eliminated the “profiles” from version 1. and established the key principles, as outlined in the original Galdos submission, as the basis of GML.

GML and G-XML (Japan)

editAs these events were unfolding, work was continuing in parallel in Japan on G-XML under the auspices of the Japanese Database Promotion Center under the direction of Mr. Shige Kawano. G-XML and GML differed in several important respects. Targeted at LBS applications, G-XML employed many concrete geographic objects (e.g. Mover, POI), while GML provided a very limited concrete set and built more complex objects by the use of application schemas. At this point in time, G-XML was still written using a DTD, while GML had already transitioned to an XML Schema. On the one hand G-XML required the use of many fundamental constructs not at the time in the GML lexicon, including temporality, spatial references by identifiers, objects having histories, and the concept of topology-based styling. GML, on the other hand, offered a limited set of primitives (geometry, feature) and a recipe to construct user defined object (feature) types.

A set of meetings held in Tokyo in January 2001, and involving Ron Lake (Galdos), Richard Martell (Galdos), OGC Staff (Kurt Buehler, David Schell), Mr. Shige Kawano (DPC), Mr. Akifumi Nakai (NTT Data) and Dr. Shimada (Hitachi CRL) led to the signing of an MOU between DPC and OGC by which OGC would endeavour to inject the fundamental elements required to support G-XML into GML, thus enabling G-XML to be written as a GML application schema. This resulted in many new types entering GML's core object list, including observations, dynamic features, temporal objects, default styles, topology, and viewpoints. Much of the work was conducted by Galdos under contract to NTT Data. This laid the foundation for GML 3, although a significant new development occurred in this time frame, namely the intersection of the OGC and ISO/TC 211.

Towards ISO – GML 3.0 broadens the scope of GML

editWhile a basic coding existed for most of the new objects introduced by the GML/G-XML agreement, and for some introduced by Galdos within the OGC process (notably coverages), it soon became apparent that few of these encodings were compliant with the abstract specifications developed by the ISO TC/211, specifications which were increasingly becoming the basis for all OGC specifications. GML geometry, for example, had been based on an earlier and only partly documented geometry model (Simple Features Geometry) and this was insufficient to support the more extensive and complex geometries described in TC/211. The management of GML development was also altered in this time frame with the participation of many more individuals. Significant contributions in this time frame were made by Milan Trninic (Galdos) (default styles, CRS), Ron Lake (Galdos) (Observations), Richard Martell (Galdos) (dynamic features).

On June 12, 2002, Mr. Ron Lake was recognized by the OGC for his work in creating GML by being presented the Gardels award.[15] The citation on the award reads “In particular, this award recognizes your great achievement in creating the Geography Markup Language, (GML), and your uniquely sensitive and effective work to promote the reconciliation of national differences to promote meaningful standardization of GML on a global level.” Simon Cox (CSIRO)[16] and Clemens Portele (Interactive Instruments)[17] also subsequently received the Gardels award, in part for their contributions to GML.

Standards

editThe Open Geospatial Consortium (OGC) is an international voluntary consensus standards organization whose members maintain the Geography Markup Language standard. The OGC coordinates with the ISO TC 211 standards organization to maintain consistency between OGC and ISO standards work. GML was adopted as an International Standard (ISO 19136:2007) in 2007.

GML can[clarification needed] also be included in version 2.1 of the United States National Information Exchange Model (NIEM).

ISO 19136

editISO 19136 Geographic information – Geography Markup Language, is a standard from the family ISO – of the standards for geographic information (ISO 191xx). It resulted from unification of the Open Geospatial Consortium definitions and Geography Markup Language (GML) with the ISO-191xx standards.

Earlier versions of GML were not ISO conformal (GML 1, GML 2) with GML version 3.1.1. ISO conformity means in particular that GML is now also an implementation of ISO 19107.

The Geography Markup Language (GML) is an XML encoding in compliance with ISO 19118 for the transport and storage of geographic information modelled according to the conceptual modelling framework used in the ISO 19100-series and including both the spatial and nonspatial properties of geographic features. This specification defines the XML Schema syntax, mechanisms, and conventions that:

- Provide an open, vendor-neutral framework for the definition of geospatial application schemas and objects;

- Allow profiles that support proper subsets of GML framework descriptive capabilities;

- Support the description of geospatial application schemas for specialized domains and information communities;

- Enable the creation and maintenance of linked geographic application schemas and datasets;

- Support the storage and transport of application schemas and data sets;

- Increase the ability of organizations to share geographic application schemas and the information they describe.

See also

edit- CityGML

- Geographic Data Files (GDF)

- GeoSPARQL – GML for geospatially-linked data and the Semantic Web

- GeoJSON

- GML Application Schemas

- ISO/TS 19103 – Conceptual Schema Language (units of measure, basic types),

- ISO 19108 – Temporal schema (temporal geometry and topology objects, temporal reference systems),

- ISO 19109 – Rules for application schemas (features),

- ISO 19111 – Spatial referencing by coordinates (coordinate reference systems),

- ISO 19123 – Coverages

- SDEP

- SOSI

- Well-known text representation of geometry

References

edit- ^ Open Geospatial Consortium Inc. (2010-02-08), Technical Committee Policies and Procedures: MIME Media Types for GML (PDF)

- ^ "OpenGIS Geography Markup Language (GML) Encoding Standard". Retrieved 2011-03-25.

- ^ "Iso 19103:2015".

- ^ "CityGML homepage". Archived from the original on 2013-02-01. Retrieved 2018-06-18.

- ^ "Climate Science Modelling Language - CSML". Archived from the original on 2015-06-13. Retrieved 2018-06-18.

- ^ "GPlates Geological Information Model : Resource Page".

- ^ "News".

- ^ "Index of /schemas". inspire.ec.europa.eu.

- ^ "NetCDF in XML". Archived from the original on 2010-03-23. Retrieved 2007-04-10.

- ^ "OS MasterMap – GML (Geography Mark-up Language) explained". Archived from the original on 2013-05-05. Retrieved 2011-10-12.

- ^ "The Home of Location Technology Innovation and Collaboration | OGC".

- ^ "KML Reference | Keyhole Markup Language". Google Developers.

- ^ "G-XML". Archived from the original on 2009-12-17.

- ^ "GML in JPEG 2000 for Geographic Imagery (GMLJP2) Encoding Specification".

- ^ "award citation for Ron Lake".

- ^ "award citation for Simon Cox".

- ^ "award citation for Clemens Portele".