Jamestown, also Jamestowne, was the first settlement of the Virginia Colony, founded in 1607, and served as the capital of Virginia until 1699, when the seat of government was moved to Williamsburg. This article covers the history of the fort and town at Jamestown proper, as well as colony-wide trends resulting from and affecting the town during the time period in which it was the colonial capital of Virginia.

Arrival and first landing

editThe London Company sent an expedition to establish a settlement in the Virginia Colony in December 1606. The expedition consisted of three ships, Susan Constant (the largest ship, sometimes known as Sarah Constant, Christopher Newport captain and in command of the group), Godspeed (Bartholomew Gosnold captain), and Discovery (the smallest ship, John Ratcliffe captain). The ships left Blackwall, now part of London, with 105 men and boys and 39 crew members.[1][2]

By April 6, 1607, Godspeed, Susan Constant, and Discovery arrived at the Spanish colony of Puerto Rico, where they stopped for provisions before continuing their journey. By the end of April, the expedition reached the southern edge of the mouth of what is now known as the Chesapeake Bay. After an unusually long journey of more than four months, the 104 men and boys (one passenger of the original 105 died during the journey) arrived at their chosen settlement spot in Virginia.[3] There were no women on the first ships.[4]

They named the Virginia capes after the sons of their king, the southern Cape Henry, for Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales, and the northern Cape Charles, for his younger brother, Charles, Duke of York. On April 26 upon landing at Cape Henry, they set up a cross near the site of the current Cape Henry Memorial, and Chaplain Robert Hunt made the following declaration:

We do hereby dedicate this Land, and ourselves, to reach the People within these shores with the Gospel of Jesus Christ, and to raise up Godly generations after us, and with these generations take the Kingdom of God to all the earth. May this Covenant of Dedication remain to all generations, as long as this earth remains. May all who see this Cross, remember what we have done here, and may those who come here to inhabit join us in this Covenant and in this most noble work that the Holy Scriptures may be fulfilled.

This site came to be known as the "first landing." A party of the men explored the area and had a minor conflict with some Virginia Indians.[5]

Exploration, seeking a site

editAfter the expedition arrived in what is now Virginia, sealed orders from the Virginia Company of London were opened. The orders named Captain John Smith as a member of the governing council. He had been arrested for mutiny during the voyage and was incarcerated aboard one of the ships. He had been scheduled to be hanged upon arrival but was freed by Captain Newport after the opening of the orders. The same orders also directed the expedition to seek an inland site for their settlement, which would afford protection from enemy ships.

Obedient to their orders, the settlers and crew members reboarded their three ships and proceeded into Chesapeake Bay. They landed again at what is now called Old Point Comfort in Hampton. In the following days, seeking a suitable location for their settlement, the ships ventured upstream along the James River. Both the James River and the settlement they sought to establish, Jamestown (originally called "James His Towne") were named in honor of King James I.

Selection of Jamestown

editOn May 14, the colonists chose Jamestown Island for their settlement largely because the Virginia Company advised them to select a location that could be easily defended from attacks by other European states that were also establishing New World colonies and were periodically at war with England, notably the Dutch Republic, France, and Spain.

The island fit the criteria as it had excellent visibility up and down the James River, and it was far enough inland to minimize the potential of contact and conflict with enemy ships. The water immediately adjacent to the land was deep enough to permit the colonists to anchor their ships, yet have an easy and quick departure if necessary. An additional benefit of the site was that the land was not occupied by the Virginia Indians, most of whom were affiliated with the Powhatan Confederacy. Largely cut off from the mainland, the shallow harbor afforded the earliest settlers docking of their ships. This was its greatest attraction, but it also created a number of challenging problems for the settlers.

Original council

editKing James I had outlined the members of the council to govern the settlement in the sealed orders which left London with the colonists in 1606.[6]

Those named for the initial council were:

- Bartholomew Gosnold, captain of Godspeed

- Christopher Newport, captain of Susan Constant, later of Sea Venture

- George Kendall, later executed for espionage

- John Martin, later founder of Martin's Brandon Plantation

- George Percy, twice president of the council

- John Ratcliffe, captain of Discovery, second president of the council

- John Smith, third President of the council and author of many books from the period

- Edward Maria Wingfield, first president of the council

Early settlement

editConstruction of the fort

editThe settlers came ashore and quickly set about constructing their initial fort. Many of the settlers who came over on the initial three ships were not well-equipped for the life they found in Jamestown. A number of the original settlers were upper-class gentlemen who were not accustomed to manual labor; the group included very few farmers or skilled laborers.[7] Also notable among the first settlers was Robert Hunt, chaplain who gave the first Christian prayer at Cape Henry on April 26, 1607, and held open-air services at Jamestown until a church was built there.

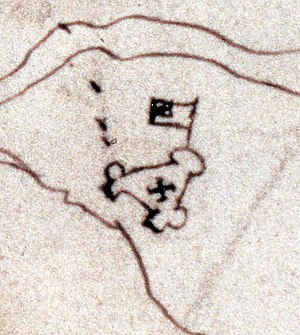

Despite the immediate area of Jamestown being uninhabited, the settlers were attacked less than two weeks after their arrival on May 14 by Paspahegh Indians who succeeded in killing one of the settlers and wounding eleven more. Within a month, James Fort covered an acre on Jamestown Island. By June 15, the settlers finished building the triangular James Fort. The wooden palisaded walls formed a triangle around a storehouse, church, and several houses. A week later, Newport sailed back for London on Susan Constant with a load of pyrite ("fools' gold") and other supposedly precious minerals, leaving behind 104 colonists and Discovery.

It soon became apparent why the Virginia Indians did not occupy the site: Jamestown Island, then a peninsula, is a swampy area, and its isolation from the mainland meant that there was limited hunting available, as most game animals require large foraging areas. The settlers quickly hunted and killed off all the large and smaller game animals that were found on the tiny peninsula. In addition, the low, marshy area was infested with airborne pests, including mosquitoes which carried malaria, and the brackish water of the tidal James River was not a good source of water. Over 135 settlers died from malaria, and drinking the salinated and contaminated water caused more deaths from salt poisoning, fevers, and dysentery. Despite their original intentions to grow food and trade with the Virginia Indians, the barely surviving colonists became dependent upon supply missions.

First supply

editNewport returned twice from England with additional supplies in the following 18 months, leading what were termed the first and second supply missions. The "first supply" arrived on January 2, 1608. It contained insufficient provisions and more than 70 new colonists.[8] Shortly after its arrival, the fort burned down.[9] The council received additional members.

Second supply

editOn October 1, 1608, 70 additional settlers arrived aboard the Mary and Margaret with the second supply, following a journey of approximately three months. Colonists on the ship included Thomas Graves, Thomas Forrest, Esq and "Mistress Forrest and Anne Burras her maide". Mistress Forrest and Anne Burras were the first two women known to have come to the Jamestown Colony. Remains unearthed at Jamestown in 1997 may be those of Mistress Forrest.[10]

Also included were the first non-English settlers. The company recruited these as skilled craftsmen and industry specialists: soap-ash, glass, lumber milling (wainscot, clapboard, and 'deal' — planks, especially soft wood planks) and naval stores (pitch, turpentine, and tar).[11][12][13][14][15][16] Among these additional settlers were eight "Dutch-men" (consisting of unnamed craftsmen and three who were probably the wood-mill-men — Adam, Franz and Samuel) "Dutch-men" (probably meaning German or German-speakers),[17] Polish and Slovak craftsmen,[11][12][13][14][15][16] who had been hired by the Virginia Company of London's leaders to help develop and manufacture profitable export products. There has been debate about the nationality of the specific craftsmen, and both the Germans and Poles claim the glassmaker for one of their own, but the evidence is insufficient.[18] Ethnicity is further complicated by the fact that the German minority in Royal Prussia lived under Polish control during this period. Originally, the colony's Polish craftsmen were barred from participating in the elections, but after the craftsmen refused to work, colonial leadership agreed to enfranchise them.[19] These workers staged the first recorded strike in Colonial America for the right to vote in the colony's 1619 election.

William Volday (Wilhelm Waldi), a Swiss German mineral prospector, was among those who arrived in 1608. His mission was seeking a silver reservoir that was believed to be within the proximity of Jamestown.[20] Some of the settlers were artisans who built a glass furnace which became the first proto-factory in British North America. Additional craftsmen produced soap, pitch, and wood building supplies. Among all of these were the first made-in-America products to be exported to Europe.[21] However, despite all these efforts, profits from exports were not sufficient to meet the expenses and expectations of the investors back in England, and no silver or gold had been discovered, as earlier hoped.

Ongoing struggles

editSmith's role

editIn the months before becoming president of the colony for a year in September 1608, Smith did considerable exploration up the Chesapeake Bay and along the various rivers. He is credited by legend with naming Stingray Point (near present-day Deltaville in Middlesex County) for an incident there. Smith was always seeking a supply of food for the colonists, and he successfully traded for food with the Nansemond Indians, who lived along the Nansemond River near the modern-day Suffolk, and several other groups. However, while leading one food-gathering expedition in December 1607 (before his term as colony president), this time up the Chickahominy River west of Jamestown, his men were set upon by the Powhatan. As his party was being slaughtered around him, Smith strapped his Native guide in front of him as a shield and escaped with his life but was captured by Opechancanough, the Powhatan chief's half-brother. Smith gave him a compass which pleased the warrior and made him decide to let Smith live.

Smith was taken before Wahunsunacock, who was commonly referred to as Chief Powhatan, at the Powhatan Confederacy's seat of government at Werowocomoco on the York River. However, 17 years later, in 1624, Smith first related that when the chief decided to execute him, this course of action was stopped by the pleas of Chief Powhatan's young daughter, Pocahontas, who was originally named "Matoaka" but whose nickname meant "Playful Mischief". Many historians today find this account dubious, especially as it was omitted in all his previous versions. Smith returned to Jamestown just in time for the first supply in January 1608.

In September 1609, Smith was wounded in an accident. He was walking with his gun in the river, and the powder was in a pouch on his belt. His powder bag exploded. In October, he was sent back to England for medical treatment. While back in England, Smith wrote A True Relation and The Proceedings of the English Colony of Virginia about his experiences in Jamestown. These books, whose accuracy has been questioned by some historians due to some extent by Smith's boastful prose, were to generate public interest and new investment for the colony.

Virginia Company of London's unrealistic expectations

editThe investors of the Virginia Company of London expected to reap rewards from their speculative investments. With the second supply, they expressed their frustrations and made demands upon the leaders of Jamestown in written form. It fell to the third president of the council to deliver a reply. By this time, Wingfield and Ratcliffe had been replaced by Smith. Ever bold, Smith delivered what must have been a wake-up call to the investors in London. In what has been termed "Smith's Rude Answer", he composed a letter, writing (in part):

When you send again I entreat you rather send but thirty Carpenters, husbandmen, gardiners, fishermen, blacksmiths, masons and diggers up of trees, roots, well provided; than a thousand of such awe have: for except wee be able both to lodge them and feed them, the most will consume with want of necessaries before they can be made good for anything.[6]

Smith did begin his letter with something of an apology, saying "I humbly intreat your Pardons if I offend you with my rude Answer...",[22] although at the time, the word 'rude' was acknowledged to mean 'unfinished' or 'rural', in the same way modern English uses 'rustic'. There are strong indications that those in London comprehended and embraced Smith's message. Their third supply mission was by far the largest and best equipped. They even had a new purpose-built flagship constructed, Sea Venture, placed in the most experienced of hands, Christopher Newport. With a fleet of no fewer than eight ships, the third supply, led by Sea Venture, left Plymouth in June 1609.

Pocahontas

editAlthough the life of Chief Powhatan's young daughter, Pocahontas, would be largely tied to the English after legend credits her with saving Smith's life after his capture by Opechancanough, her contacts with Smith were minimal. However, records indicate that she became something of an emissary to the colonists at Jamestown Island. During their first winter, following an almost complete destruction of their fort by a fire in January 1608, Pocahontas brought food and clothing to the colonists. She later negotiated with Smith for the release of Virginia Indians who had been captured by the colonists during a raid to gain English weaponry.

During the next several years, the relationship between the Virginia Indians and the colonists became more strained, never more so than during the period of poor crops for both the natives and colonists which became known as the Starving Time in late 1609 and early 1610. Chief Powhatan relocated his principal capital from Werowocomoco, which was relatively close to Jamestown along the north shore of the York River, to a point more inland and secure along the upper reaches of the Chickahominy River.

In April 1613, Pocahontas and her husband, Kocoum were residing at Passapatanzy, a village of the Patawomecks, a Powhatan Confederacy tribe which did some trading with Powhatans[citation needed]. They lived in present-day Stafford County on the Potomac River near Fredericksburg, about 65 miles (105 km) from Werowocomoco[citation needed]. She was abducted by Englishmen whose leader was Samuel Argall and transported about 90 miles (140 km) south to the English settlement at Henricus on the James River. There, Pocahontas converted to Christianity and took the name "Rebecca" under the tutelage of Reverend Alexander Whitaker who had arrived in Jamestown in 1611.

She married prominent planter John Rolfe who had lost his first wife and child in the journey from England several years earlier, which served to greatly improve relations between the Virginia Native Americans and the colonists for several years. However, when she and Rolfe took their young son Thomas Rolfe on a public relations trip to England to help raise more investment money for the Virginia Company, she became ill and died just as they were leaving to return to Virginia. Her interment was at St George's Church in Gravesend.

Starving Time

editWhat became known as the "Starving Time" in the Virginia Colony occurred during the winter of 1609–10, when only 60 of 500 English colonists survived.[23][24][25] The colonists had never planned to grow all of their own food. Instead, their plans depended upon trade with the local Virginia Indians to supply them with enough food between the arrival of periodic supply ships from England, upon which they also relied. This period of extreme hardship for the colonists began in 1609 with a drought which caused their already limited farming activities to produce even fewer crops than usual. Then, there were problems with both of their other sources for food. An unexpected delay occurred during the Virginia Company of London's third supply mission from England, so much-needed food and supplies were unavailable for the winter.

After Smith left for England to tend to his injuries, Chief Powhatan severely curtailed trading with the colonists for food. Instead, the Powhatans used the prospect of trading for corn to betray an expedition led by Smith's successor, John Ratcliffe.[26] Ratcliffe was lured by the prospect of food but was kidnapped, tortured, and murdered by the Powhatans.[27] Neither the missing Sea Venture nor any other supply ship arrived as winter set upon the inhabitants of the young colony in late 1609.

Third supply

editLeaving England in 1609, Vice-Admiral Christopher Newport was in charge of a nine-vessel fleet. Aboard the flagship Sea Venture was the Admiral of the company, George Somers, Lieutenant-General Thomas Gates, William Strachey and other notable personages in the early history of English colonization in North America.

While at sea, the fleet encountered a strong storm, perhaps a hurricane, which lasted for three days. Sea Venture and one other ship were separated from the seven other vessels of the fleet. Sea Venture was deliberately driven onto the reefs of Bermuda to prevent her sinking. The 150 passengers and crew members were all landed safely, but the ship was permanently damaged.[28] Sea Venture's longboat was later fitted with a mast and sent to find Virginia, but it and its crew were never seen again. The remaining survivors spent nine months on Bermuda building two smaller ships, Deliverance and Patience, from Bermuda cedar and materials salvaged from Sea Venture.

The survivors of the shipwreck of Sea Venture finally arrived at Jamestown the following May 23, 1610. They found the Virginia Colony in ruins and practically abandoned: of 500 settlers who had preceded them to Jamestown, they found fewer than 100 survivors, many of whom were sick or dying. Worse yet, the Bermuda survivors had brought few supplies and only a small amount of food with them, expecting to find a thriving colony at Jamestown.

Thus, even with the arrival of the two small ships from Bermuda under Newport, they were faced with leaving Jamestown and returning to England. On June 7, having abandoned the fort and many of their possessions, both groups of survivors (from Jamestown and Bermuda) boarded ships, and they all set sail down the James River toward the Chesapeake Bay and the Atlantic Ocean.

Lord De La Warr

editDuring the same period that Sea Venture suffered its misfortune and its survivors were struggling in Bermuda to continue on to Virginia, back in England, the publication of Captain John Smith's books of his adventures in Virginia sparked a resurgence in interest in the colony. This helped lead to the dispatch in early 1610 of additional colonists, more supplies, and a new governor, Thomas West, Baron De La Warr. Fortuitously, on June 9, 1610, De La Warr arrived on the James River just as the settlers had abandoned Jamestown. Intercepting them about 10 miles (16 km) downstream from Jamestown near Mulberry Island (adjacent to present-day Fort Eustis in Newport News), the new governor forced the remaining 90 settlers to return. Deliverance and Patience turned back, and all the settlers were landed again at Jamestown.[29] With the new supply mission, the De La Warr brought additional colonists, a doctor, food, and much-needed supplies. De La Warr proved to be a new kind of leader for Virginia.

Somers returned to Bermuda with Patience to obtain more food supplies, but he died on the island that summer. His nephew, Matthew Somers, captain of Patience, took the ship back to Lyme Regis, England instead of Virginia (leaving a third man behind). The Third Charter of the Virginia Company was then extended far enough across the Atlantic to include Bermuda in 1612. (Although a separate company, the Somers Isles Company, would be spun off to administer Bermuda from 1615, the first two successful English colonies would retain close ties for many more generations, as was demonstrated when Virginian general George Washington called upon the people of Bermuda for aid during the American War of Independence). In 1613, Thomas Dale founded the settlement of Bermuda Hundred on the James River, which, a year later, became the first incorporated town in Virginia.

Expansion beyond Jamestown

editBy 1611, a majority of the colonists who had arrived at the Jamestown settlement had died, and its economic value was negligible with no active exports to England and very little internal economic activity. Only financial incentives to investors financing the new colony, including a promise of more land to the west from King James I, kept the project afloat.

First Anglo-Powhatan War

editThe Anglo-Powhatan Wars were three wars fought between English settlers of the Virginia Colony, and Indians of the Powhatan Confederacy in the early seventeenth century. The First War started in 1610, and ended in a peace settlement in 1614.

Tobacco

editIn 1610, John Rolfe, whose wife and a child had died in Bermuda during passage in the third supply to Virginia, was just one of the settlers who had arrived in Jamestown following the shipwreck of Sea Venture. Rolfe was the first man to successfully raise export tobacco in the colony (although the colonists had begun to make glass artifacts to export immediately after their arrival). The native tobacco raised in Virginia prior to that time, Nicotiana rustica, was not to the liking of the Europeans, but Rolfe had brought some seed of Nicotiana tabacum with him from Bermuda. Although most people "wouldn't touch" the crop, Rolfe was able to make his fortune farming it, successfully exporting beginning in 1612. Soon almost all other colonists followed suit, as windfall profits in tobacco briefly lent Jamestown something like a gold rush atmosphere.

Governor Dale, Dale's Code

editIn 1611, the Virginia Company of London sent Thomas Dale to act as deputy-governor or as high marshall for the Virginia Colony under the authority of Lord De La Warr. He arrived at Jamestown on May 19 with three ships, additional men, cattle, and provisions. Finding the conditions unhealthy and greatly in need of improvement, he immediately called for a meeting of the Jamestown Council and established crews to rebuild Jamestown.

He served as governor for 3 months in 1611 and again for a two-year period between 1614 and 1616. It was during his administration that the first code of laws of Virginia, nominally in force from 1611 to 1619, was effectively tested. This code, entitled "Articles, Lawes, and Orders Divine, Politique, and Martiall" (popularly known as Dale's Code), was notable for its pitiless severity and seems to have been prepared in large part by Dale.

Henricus

editSeeking a better site than Jamestown with the thought of possibly relocating the capital, Dale sailed up the James to the area now known as Chesterfield County. He was apparently impressed with the possibilities of the general area where the Appomattox River joins the James River, occupied by the Appomattoc Indians, and there are published references to the name "New Bermudas" although it apparently was never formalized. A short distance further up the James, in 1611 he began the construction of a progressive development at Henricus on and about what was later known as Farrar's Island. Henricus was envisioned as possible replacement capital for Jamestown, though it was eventually destroyed during the Indian massacre of 1622, during which a third of the colonists were killed.

An investor relations trip to England

editIn 1616, Governor Dale joined Rolfe and Pocahontas and their young son Thomas as they left their Varina Farms plantation for a public relations mission to England, where Pocahontas was received and treated as a form of visiting royalty by Queen Anne. This stimulated more interest in investments in the Virginia Company, the desired effect. However, as the couple prepared to return to Virginia, Pocahontas died of an illness at Gravesend on March 17, 1617, where she was buried. John Rolfe returned to Virginia alone once again, leaving their son in England to obtain an education.

Once back in Virginia, Rolfe married Jane Pierce and continued to improve the quality of his tobacco with the result that by the time of his death in 1622, the colony was thriving as a producer of tobacco. Orphaned by the age of 8, young Thomas later returned to Virginia and settled across the James River not far from his parents' farm at Varina, where he married Jane Poythress and they had one daughter, Jane Rolfe, who was born in 1650. Many of the First Families of Virginia trace their lineage through Thomas Rolfe to both Pocahontas and John Rolfe, joining English and Virginia Indian heritage.

Changing social and political order

editVirginia's population grew rapidly from 1618 until 1622, rising from a few hundred to nearly 1,400 people. Wheat was also grown in Virginia starting in 1618. The General Assembly, the first elected representative legislature in the New World, met in the choir of the Jamestown Church from July 30 to August 4, 1619. This legislative body continues as today's Virginia General Assembly.[30]

In August 1619, "20 and odd Negroes" arrived on a Dutch man-of-war ship at Point Comfort, several miles south of the Jamestown colony. This is the earliest record of Africans in colonial America.[31] These colonists were freemen and indentured servants.[32][33][34][35] At this time the slave trade between Africa and the English colonies had not yet been established.

Records from 1623 and 1624 listed the African inhabitants of the colony as servants, not slaves. In the case of William Tucker, the first black person born in the colonies, freedom was his birthright.[36] He was son of "Antony and Isabell", a married couple from Angola who worked as indentured servants for Captain William Tucker whom he was named after. Yet, court records show that at least one African had been declared a slave by 1640; John Punch. He was an indentured servant who ran away along with two white indentured servants, and he was sentenced by the governing council to lifelong servitude. This action is what officially marked the institution of slavery in Jamestown and the future United States.

By 1620, more German settlers arrived from Hamburg, Germany, who were recruited by the Virginia Company set up and operated one of the first sawmills in the region.[37] Among the Germans were several other skilled craftsmen carpenters, and pitch/tar/soap-ash makers, who produced some of the colony's first exports of these products. The Italians included a team of glass makers.[38] On June 30, 1619, Slovak and Polish artisans conducted the first labor strike in American history[39][19] for democratic rights[39][40] in Jamestown.[40][41][42][43] The workers were granted equal voting rights on July 21, 1619.[44] Afterwards, the labor strike was ended, and the artisans resumed their work.[41][42][45][46]

During 1621 fifty-seven unmarried women sailed to Virginia under the auspices of the Virginia Company, who paid for their transport and provided them with a small bundle of clothing and other goods to take with them. A colonist who married one of the women would be responsible for repaying the Virginia Company for his wife's transport and provisions. The women traveled on three ships, The Marmaduke, The Warwick, and The Tyger. Many of the women were not "maids" but widows. Some others were children, for example Priscilla, the eleven-year-old daughter of Joan and Thomas Palmer on the Tyger. Some were women who were traveling with family or relatives: Ursula Clawson, "kinswoman" of ancient planter Richard Pace, traveled with Pace and his wife on the Marmaduke. There were a total of twelve unmarried women on the Marmaduke, one of whom was Ann Jackson, daughter of William Jackson of London. She joined her brother John Jackson who was already in Virginia, living at Martin's Hundred. Ann was one of nineteen women kidnapped by the Powhatans during the Indian massacre of 1622 and was not returned until 1628, when the council ordered her brother John to keep Ann in safety until she returned to England on the first available ship.[47] Some of the women sent to Virginia did marry. Most disappeared from the records—perhaps killed in the massacre, perhaps dead from other causes, perhaps returned to England. In other words, they shared the fate of most of their fellow colonists.[48]

Indian massacre of 1622

editThe relations with the natives took a turn for the worse after the death of Pocahontas in England and the return of Rolfe and other colonial leaders in May 1617. Disease, poor harvests and the growing demand for tobacco lands caused hostilities to escalate. After Wahunsunacock's death in 1618, his younger brother, Opitchapam, briefly became chief. However, he was soon succeeded by his own younger brother, Opechancanough. Opechancanough was not interested in attempting peaceful coexistence with the English settlers. Instead, he was determined to eradicate the colonists from what he considered to be Indian lands. As a result, another war between the two powers lasted from 1622 to 1632.

Chief Opechancanough organized and led a well-coordinated series of surprise attacks on multiple English settlements along both sides of a 50-mile (80 km) long stretch of the James River which took place early on the morning of March 22, 1622. This event resulted in the deaths of 347 colonists (including men, women, and children) and the abduction of many others. The massacre caught most of the Virginia Colony by surprise and virtually wiped out several entire communities, including Henricus and Wolstenholme Towne at Martin's Hundred. A letter by Richard Frethorne, written in 1623, reports, "we live in fear of the enemy every hour."[49]

However, Jamestown was spared from destruction because an Indian boy named Chanco, after learning of the planned attacks from his brother, gave warning to colonist Richard Pace, with whom he lived. Pace, after securing himself and his neighbors on the south side of the James River, took a canoe across river to warn Jamestown, which narrowly escaped destruction, although there was no time to warn the other settlements. Apparently, Opechancanough subsequently was unaware of Chanco's actions, as the young man continued to serve as his courier for some time after.

Royal colony

editSome historians have noted that, as the settlers of the Virginia Colony were allowed some representative government, and they prospered, King James I was reluctant to lose either power or future financial potential. In any case, in 1624, the Virginia Company lost its charter, and Virginia became a crown colony. In 1634, the English Crown created eight shires which had a total population of approximately 5,000. James City Shire was established and included Jamestown. Around 1642–43, the name of the James City Shire was changed to James City County.

New Town and palisade

editThe original Jamestown fort seems to have existed into the middle of the 1620s, but as Jamestown grew into a "New Town" to the east, written references to the original fort disappear. By 1634, a palisade (stockade) was completed across the Virginia Peninsula, which was about 6 miles (9.7 km) wide at that point between Queen's Creek which fed into the York River and Archer's Hope Creek, (since renamed College Creek) which fed into the James River. The palisade provided some security from attacks by the Virginia Indians for colonists farming and fishing lower on the peninsula from that point.

Third Anglo-Powhatan War

editOn April 18, 1644, Opechancanough again tried to force the colonists to abandon the region with another series of coordinated attacks, killing almost 500 colonists. However, this was a much less devastating portion of the growing population than had been the case in the 1622 attacks. Furthermore, the forces of Royal Governor of Virginia William Berkeley captured Opechancanough in 1646,[50] variously thought to be between 90 and 100 years old. In October, while a prisoner, Opechancanough was killed by a soldier (shot in the back) assigned to guard him. Opechancanough was succeeded as weroance (chief) by Necotowance and then by Totopotomoi and later by his daughter Cockacoeske.

In 1646, the first treaties were signed between the Virginia Indians and the English. The treaties set up reservations, some of the oldest in America, for the surviving Powhatan. It also set up tribute payments for the Virginia Indians to be made yearly to the English.[51] That war resulted in a boundary being defined between the Indians and English lands that could only be crossed for official business with a special pass.

Bacon's Rebellion

editBacon's Rebellion was an armed rebellion in 1676 by Virginia settlers led by Nathaniel Bacon against the rule of Governor William Berkeley. In the 1670s, the governor was serving his second term in office. Berkeley had previously been governor in the 1640s and had experimented with export crops at his Green Spring Plantation near Jamestown. In the mid-1670s, a young cousin through marriage, Nathaniel Bacon, Jr., arrived in Virginia sent by his father in the hope that he would "mature" under the tutelage of the governor. Although lazy, Bacon was intelligent, and Berkeley provided him with a land grant and a seat on the Virginia Colony council. However, the two became at odds over relationships with the Virginia Indians, which were most strained at the outer frontier points of the colony.

In July 1675, Doeg Indians crossed from Maryland and raided the plantation of Thomas Mathews in the northern portion of the colony along the Potomac River, stealing some hogs in order to gain payment for several items Mathews had obtained from the tribe. Mathews pursued them and killed several Doegs, who retaliated by killing Mathews' son and two of his servants, including Robert Hen. A Virginian militia then went to Maryland and besieged the Susquehanaugs (a different tribe) in "retaliation" which led to even more large-scale Indian raids, and a protest from the governor of Maryland colony. Berkeley tried to calm the situation, but many of the colonists, particularly the frontiersmen, refused to listen to him. Bacon disregarded a direct order and captured some Appomattoc Indians who were located many miles south of the site of the initial incident and almost certainly not involved.

Following the establishment of the Long Assembly in 1676, war was declared on "all hostile Indians," and trade with Indian tribes became regulated, often seen by the colonists to favor friends of Berkeley. Bacon led a group in opposition to the governor. Bacon led numerous raids on Indians friendly to the colonists in an attempt to bring down Berkeley. The governor offered him amnesty, but the House of Burgesses refused; insisting that Bacon must acknowledge his mistakes. At about the same time, Bacon was actually elected to the House of Burgesses and attended the June 1676 assembly where he was captured, forced to apologize and was then pardoned by Berkeley.

Bacon then demanded a military commission, but Berkeley refused. Bacon and his supporters surrounded the statehouse and threatened to start shooting the Burgesses if Berkeley did not acknowledge Bacon as "General of all forces against the Indians". Berkeley eventually acceded, and then left Jamestown. He attempted a coup a month later but was unsuccessful. In September, however, Berkeley was successful and occupied Jamestown. Bacon's forces arrived and dug in for a siege, which resulted in Bacon's capturing and burning Jamestown to the ground on September 19, 1676.[52] Bacon died of dysentery on October 26, 1676, and his body is believed to have been burned.

Berkeley returned and hanged William Drummond and the other major leaders of the rebellion (23 in total) at Middle Plantation. With Jamestown unusable due to the burning by Bacon, the Governor convened a session of the General Assembly at his Green Spring Plantation in February, 1677, and another was later held at Middle Plantation. However, upon learning of his actions, King Charles II was reportedly displeased at the degree of retaliation and number of executions, and he recalled Berkeley to England. He returned to London where he died in July 1677.

The capital moves from Jamestown to high ground

editDespite the periodic need to relocate the legislature from Jamestown due to contingencies such as fires, (usually to Middle Plantation), throughout the 17th century, Virginians had been reluctant to permanently move the capital from its "ancient and accustomed place." After all, Jamestown had always been Virginia's capital. It had a state house (except when it periodically burned) and a church, and it offered easy access to ships that came up the James River bringing goods from England and taking on tobacco bound for market.[53] However, Jamestown's status had been in some decline. In 1662, Jamestown's status as mandatory port of entry for Virginia had been ended.

On October 20, 1698, the statehouse (capitol building) in Jamestown burned for the fourth time. Once again removing itself to a familiar alternate location, the legislature met at Middle Plantation, this time in the College Building at the College of William & Mary, which had begun meeting there in temporary quarters in 1694. While meeting there, a group of five students from the college submitted a well-presented and logical proposal to the legislators outlining a plan and good reasons to move the capital permanently to Middle Plantation. The students argued that the change to the high ground at Middle Plantation would escape the dreaded malaria and mosquitoes that had always plagued the swampy, low-lying Jamestown site. The students pointed out that, while not located immediately upon a river, Middle Plantation offered nearby access to not one, but two rivers, via two deep water (6-7' depth) creeks, Queen's Creek leading to the York River, and College Creek which led to the James River.

Several prominent individuals like John Page, Thomas Ludwell, Philip Ludwell, and Otho Thorpe had built fine brick homes and created a substantial town at Middle Plantation. Other advocates of the move included the Reverend Dr. James Blair and Governor Francis Nicholson. The proposal to move the capital of Virginia to higher ground (about 12 miles (20 km) away) at Middle Plantation was received favorably by the House of Burgesses. In 1699, the capital of the Virginia Colony was officially relocated there. The town was renamed Williamsburg, in honor of King William III.

Later history

editBy the 1750s the land was owned and heavily cultivated, primarily by the Travis and Ambler families. A military post was located on the island during the American Revolutionary War and American and British prisoners were exchanged there. During the American Civil War the island was occupied by Confederate soldiers who built an earth fort near the church as part of the defense system to block the Union advance up the river to Richmond. Little further attention was paid to Virginia until preservation was undertaken in the 21st century.

The U.S. Post Office issued a set of stamps on the 300th anniversary of the founding of the Jamestown colony.

References

edit- ^ Congressional Record (1975). "Congressional Record 1975". Congressional Record. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- ^ Congressional Record (1976). "Congressional Record 1976". Congressional Record. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- ^ Lisa L. Weaver (8 June 2000). Learning Landscapes: Theoretical Issues and Design Considerations for the Development of Children's Educational Landscapes (PDF) (Thesis). Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University. hdl:10919/34095. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-02-05. Retrieved 2020-09-26.

- ^ Kathleen M. Brown. "Women in Early Jamestown". Jamestown Interpretive Essays. Virtual Jamestown. Retrieved 2006-12-19.

- ^ "Virginia Secretary of Natural Resources - Doug Domenech" (PDF). Indians.vipnet.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-02-24. Retrieved 2013-10-26.

- ^ a b "Virginia's History". Xroads.virginia.edu. Archived from the original on 2016-04-18. Retrieved 2012-05-24.

- ^ "Original Settlers". Preservation Virginia. Retrieved 8 June 2011.

- ^ "First Supply". Preservation Virginia. Archived from the original on 7 October 2011. Retrieved 8 June 2011.

- ^ "History of Jamestown - Jamestown Rediscovery". Apva.org. Archived from the original on 2009-04-16. Retrieved 2013-10-26.

- ^ "Jamestown's First Lady - Archaeology Magazine Archive".

- ^ a b Congressional Record (July 5, 1956). "Congressional Record - 1956". Congressional Record. pp. 11905–11906. Retrieved October 1, 2014.

- ^ a b Congressional Record (1975). "Congressional Record 1975". Congressional Record. Retrieved October 1, 2014.

- ^ a b Congressional Record (1976). "Congressional Record 1976". Congressional Record. Retrieved October 1, 2014.

- ^ a b Eisenhower, Dwight D. (September 28, 1958). "Jamestown Pioneers From Poland". White House. Retrieved October 1, 2014.

- ^ a b Henderson, George; Olasij, Thompson Dele (January 10, 1995). Migrants, Immigrants, and Slaves: Racial and Ethnic Groups in America. University Press of America. p. 116. ISBN 978-0819197382. Retrieved October 1, 2014.

- ^ a b Robertson, Patrick (November 8, 2011). Robertson's Book of Firsts: Who Did What for the First Time. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. ISBN 978-1596915794. Retrieved October 2, 2014.

- ^ "Jamestown Dutchmen". Kismeta.com. Archived from the original on July 5, 2008. Retrieved 2008-05-03.

- ^ "Precursor Light Industry in Support of the Jamestown Glass works". Retrieved 2007-03-03.

- ^ a b Grizzard, Frank E.; Smith, Boyd D. (2007). Jamestown Colony: A Political, Social, and Cultural History. ABC-CLIO. p. 171. ISBN 978-1-85109-637-4.

- ^ "First Germans in the colonies". Germanheritage.com. Archived from the original on 2017-01-25. Retrieved 2006-10-10.

- ^ "First Polish Settlers". Polishamericancenter.org. Retrieved 2013-10-26.

- ^ "Presentations and Activities - For Teachers (Library of Congress)". Memory.loc.gov. Retrieved 2012-05-24.

- ^ "Girl's Bones Bear Signs of Cannibalism by Starving Virginia Colonists". The New York Times. Retrieved 2013-10-26.

- ^ Bryan, Corbin Braxton. The Church at Jamestown in Clark, W. M., ed. Colonial Churches in the Original Colony of Virginia. 2d. ed. Richmond, VA: Southern Churchman Company, 1908. OCLC 1397138. p. 20.

- ^ Beverley, Robert. The History of Virginia in Four Parts. Richmond, VA: J. W. Randolph, 1855. OCLC 5837141. 2d revised edition originally published London: 1722. p. 26.

- ^ "Chesapeake Bay - Native Americans - The Mariners' Museum". www.marinersmuseum.org. Retrieved 2018-09-24.

- ^ Strong, Pauline Turner (2018-02-19). Captive Selves, Captivating Others: The Politics And Poetics Of Colonial American Captivity Narratives. Routledge. ISBN 9780429981487.

- ^ Woodward, Hobson. A Brave Vessel: The True Tale of the Castaways Who Rescued Jamestown and Inspired Shakespeare's The Tempest. Viking (2009).

- ^ Because Jamestown was abandoned for two days in June 1610, while Fort Algernon, built in October 1609, was never abandoned, the modern city of Hampton, Virginia puts in a competing claim as "the oldest continuous English-speaking settlement in North America". Rountree 1990 p.53, 54n.

- ^ Horn, James P. P: 1619; Jamestown and the Forging of American Democracy; (New York, Basic Books, 2018)

- ^ "John Rolf Reports on Virginia to Sir Edwin Sandys, 1619 - American Memory Timeline- Classroom Presentation | Teacher Resources - Library of Congress". www.loc.gov. Retrieved 2018-01-03.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-02-26. Retrieved 2014-12-27.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Colonial WIlliamsburg, WInter 2010. "Slavery, Freedom, and Fort Monroe" (PDF). Retrieved 2018-01-04.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Wagner, Margaret E.; Gallagher, Gary W.; McPherson, James M. (24 November 2009). The Library of Congress Civil War Desk Reference. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9781439148846. Retrieved 12 October 2016 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-01-03. Retrieved 2014-12-27.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "African American Men: Moments in History from Colonial Times to the Present". www.washingtonpost.com. Retrieved 2018-01-03.

- ^ "German sawmill in 1620". Germanheritage.com. Retrieved 2006-10-10.

- ^ "German and Polish craftsmen in Jamestown". Germanheritage.com. Retrieved 2006-10-10.

- ^ a b Holshouser, Joshua D.; Brylinsk-Padnbey, Lucyna; Kielbasa, Katarzyna (July 2007). "Jamestown: The Birth of American Polonia 1608-2008 (The Role and Accomplishments of Polish Pioneers in the Jamestown Colony)". Polish American Congress. Archived from the original on July 24, 2015. Retrieved October 3, 2014.

- ^ a b Odrowaz-Sypniewska, Margaret (Jun 29, 2007). "Poles and Powhatans in Jamestown, Virginia (1606-1617)". Retrieved October 3, 2014.

- ^ a b Badaczewski, Dennis (February 28, 2002). Poles in Michigan. Michigan State University Press. ISBN 978-0870136184.

- ^ a b Staff. "Spuscizna - History of Poles in the USA". The Spuscizna Group. Retrieved October 3, 2014.

- ^ ushistory.org. "The House of Burgesses". Ushistory.org. Retrieved 2013-07-10.

- ^ Obst, Peter J. (July 20, 2012). "Dedication of Historical Marker to Honor Jamestown Poles of 1608 - The First Poles in Jamestown". Poles.org. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

- ^ Smith, John (1624). "VII". The generall historie of Virginia, New England & the Summer Isles, together with The true travels, adventures and observations. Vol. 1. American Memory. pp. 150–184. Retrieved October 3, 2014.

- ^ Seroczynski, Felix Thomas (1911). Poles in the United States. Vol. XII. Catholic Encyclopedia. Retrieved October 3, 2014.

- ^ Fausz, J. Frederick, "Powhatan Uprising of 1622", American History Magazine, March 1998

- ^ "The Ferrar Papers 1590-1790" (PDF). Microform.co.uk. Retrieved 2013-10-26.

- ^ Frethorne, Richard. Richard Frethorne to his father and mother, March 20, April 2 and 3, 1623 Archived 2013-09-26 at the Wayback Machine (Electronic Text Center, University of Virginia Library).

- ^ Rountree, Helen C. Pocahontas, Powhatan, Opechancanough: Three Indian Lives Changed by Jamestown. University of Virginia Press: Charlottesville, 2005

- ^ We're Still Here: Virginia Indians Tell Their Stories by Sandra F. Waugaman and Danielle Moretti-Langholtz, Ph.D.

- ^ McCulley, Susan (June 1987). "Bacon's Rebellion". nps.gov. National Park Service. Retrieved October 6, 2015.

- ^ Jones, Jennifer (2009-11-05). "Middle Plantation". Research.history.org. Archived from the original on 2012-02-04. Retrieved 2012-05-24.

Further reading

edit- Bernard Bailyn, The Barbarous Years: The Peopling of British North America: The Conflict of Civilizations, 1600-1675 (Vintage, 2012)

- Warren M. Billings (Editor), The Old Dominion in the Seventeenth Century: A Documentary History of Virginia, 1606-1700 (University of North Carolina Press, 2007)

- James Horn, A Land as God Made It (Perseus Books, 2005)

- Margaret Huber, Powhatan Lords of Life and Death: Command and Consent in Seventeenth-Century Virginia (University of Nebraska Press, 2008)

- William M. Kelso, Jamestown, The Buried Truth (University of Virginia Press, 2006)

- David A. Price, Love and Hate in Jamestown (Alfred A. Knopf, 2003)

- Helen C. Rountree, The Powhatan Indians of Virginia: Their Traditional Culture (University of Oklahoma Press, 2013)

- Ed Southern (Editor), Jamestown Adventure, The: Accounts of the Virginia Colony, 1605-1614 (Blair, 2011)

- Jocelyn R. Wingfield, Virginia's True Founder: Edward Maria Wingfield and His Times (Booksurge, 2007)

- Benjamin Woolley, Savage Kingdom: The True Story of Jamestown, 1607, and the Settlement of America (Harper Perennial, 2008)

- William M. Kelso, Nicholas M. Luccketti, Beverly A. Straube, The Jamestown Rediscovery Archaeology Project

External links

edit- Historic Jamestowne

- Jamestown 1607

- America's 400th Anniversary

- APVA web site for the Jamestown Rediscovery project

- National Geographic Magazine Jamestown Interactive[dead link]

- Jamestown Settlement and Yorktown Victory Center

- Virtual Jamestown

- National Park Service: Jamestown National Historic Site

- New Discoveries at Jamestown by John L. Cotter and J. Paul Hudson, (1957) at Project Gutenberg

- First Landing State Park

- State Tourism Website – Virginia is for Lovers

- Jamestown Discovery Trail

- Time Team Special: Jamestown – America's Birthplace

- Following in Godspeeds Wake

- NBC News Interview with Dr. William Kelso[permanent dead link]

- History Channel Web Site

- Geographical coordinates: 37°12′33″N 76°46′39″W / 37.20917°N 76.77750°W