Hindush (Old Persian: 𐏃𐎡𐎯𐎢𐏁 Hidūš)[a] was an administrative division of the Achaemenid Empire in modern-day Pakistan. According to the Greek historian Herodotus, it was the "easternmost province" governed by the Achaemenid dynasty. Established through the Persian conquest of the Indus Valley in the 6th century BCE, it is believed to have continued as a province for approximately two centuries, ending when it fell to the Macedonian Empire during the Indian campaign of Alexander the Great.

| Hindush 𐏃𐎡𐎯𐎢𐏁 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Satrapy of the Achaemenid Empire | |||||||||

| c. 513 BCE–c. 325 BCE | |||||||||

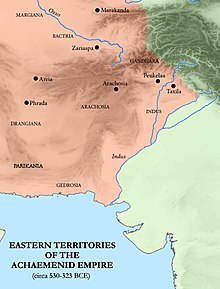

Approximate territorial extent of the Achaemenid realm in the Indus Valley | |||||||||

| Government | |||||||||

| • Type | Monarchy | ||||||||

| Monarchs | |||||||||

• 513–499 BCE | Darius I (first) | ||||||||

• 336–330 BCE | Darius III (last) | ||||||||

| Historical era | Iron Age | ||||||||

| c. 513 BCE | |||||||||

| c. 325 BCE | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Pakistan | ||||||||

Etymology

editHindush was written in Persian inscriptions as Hidūsh (Old Persian cuneiform: 𐏃𐎡𐎯𐎢𐏁, H-i-du-u-š). It is also transliterated as Hiⁿdūš since the nasal "n" before consonants was omitted in the Old Persian script, and simplified as Hindush.[2][3]

It is widely accepted that the name Hindush derives from Sindhu, the Sanskrit name of the Indus river as well as the region at the lower Indus basin. The Proto-Iranian sound change *s > h occurred between 850–600 BCE, according to Asko Parpola.[4] The -sh suffix is common among the names of many Achaemenid provinces, such as Harauvatish (the land of Harauvati or Haraxvaiti, i.e., Arachosia) or Bakhtrish (Bactria). Accordingly, Hindush would mean the land of Sindhu.

The Greeks of Asia Minor, who were also part of the Achaemenid empire, called the province 'India'. More precisely, they called the people of the province as 'Indians' ('Ινδοι, Indoi[5]) The loss of the aspirate /h/ was probably due to the dialects of Greek spoken in Asia Minor.[6][7] Herodotus also generalised the term "Indian" from the people of Hindush to all the people living to the east of Persia, even though he had no knowledge of the geography of the land.[8]

Geography

editThe territory of Hindush may have corresponded to the area covering the lower and central Indus basin (present day Sindh and the southern Punjab region of Pakistan).[9][10][11] Hindush bordered Gandāra (spelt as Gaⁿdāra by the Achaememids) to the north. These areas remained under Persian control until the invasion by Alexander.[12] Alternatively, some authors consider that Hindush may have been located in the Punjab region.[10][13]

Integration

editSecond Persian invasion of Greece

editAccording to Herodotus, the 'Indians' participated to the Second Persian invasion of Greece circa 480 BCE.[16] At the final Battle of Platea (479 BCE), they formed one of the main corps of Achaemenid troops (one of "the greatest of the nations").[17][18] Indians were still supplying troops and elephants for the Achaemenid army at the Battle of Gaugamela (331 BCE).[19] They are also depicted on the Achaemenid tombs of Naqsh-e Rostam and Persepolis.

Demographic representation

editRepresentatives of Hindush are depicted as delegates bringing gifts to the king on the Apadana staircases, and as throne/ dais bearers on the Tripylon and Hall of One Hundred Columns reliefs at Persepolis The representatives of Hindush (as well as Gandara and Thatagus) in each in- stance are characterized by their loincloths, sandals, and exposed upper body, which distinguish them from the representatives of other eastern provinces such as Bactria and Arachosia.[20]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ Transcribed as Hiⁿdūš because the nasal "n" before consonants was omitted in the Old Persian script, and simplified as Hindūš.

References

edit- ^ "Arachosia, Sattagydia, and India are represented and named among the subject nations sculptured on the base of the Egyptian statue of Darius I from Susa."Yar-Shater, Ehsan (1982). Encyclopaedia Iranica. Routledge & Kegan Paul. p. 10. ISBN 9780933273955.

- ^ Some sounds are omitted in the writing of Old Persian, and are shown with a raised letter.Old Persian p.164Old Persian p.13. In particular Old Persian nasals such as "n" were omitted in writing before consonants Old Persian p.17Old Persian p.25

- ^ DNa - Livius.

- ^ Parpola, Asko (2015). The Roots of Hinduism. Oxford University Press. Chapter 9.

- ^ 'Ινδοι, Greek Word Study Tool, Tufts University

- ^ Horrocks, Geoffrey (2009), Greek: A History of the Language and its Speakers (Second ed.), John Wiley & Sons, pp. 27–28, ISBN 978-1-4443-1892-0: "Note finally that the letter H/η was originally used to mark word-initial aspiration... Since such aspiration was lost very early in the eastern Ionic-speaking area, the letter was recycled, being used first to denote the new, very open, long e-vowel [æ:] ... and then to represent the inherited long e-vowel [ε:] too, once these two sounds had merged. The use of H to represent open long e-vowels spread quite early to the central Ionic-speaking area and also to the Doric-speaking islands of the southern Aegean, where it doubled up both as the marker of aspiration and as a symbol for open long e-vowels."

- ^ Panayotou, A. (2007), "Ionic and Attic", in A.-F. Christidis (ed.), A History of Ancient Greek: From the Beginnings to Late Antiquity, Cambridge University Press, p. 410, ISBN 978-0-521-83307-3: "The early loss of aspiration is mainly a characteristic of Asia Minor (and also of the Aeolic and Doric of Asia Minor)...In Attica, however (and in some cases in Euboea, its colonies, and in the Ionic-speaking islands of the Aegean), the aspiration survived until later... During the second half of the fifth century BC, however, orthographic variation perhaps indicates that 'a change in the phonetic quality of [h] was taking place' too."

- ^ Arora, Udai Prakash (2005), "Ideas of India in Ancient Greek Literature", in Irfan Habib (ed.), India — Studies in the History of an Idea, Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers, p. 47, ISBN 978-81-215-1152-0: "The term 'Indians' was used by Herodotus as a collective name for all the peoples living east of Persia. This was also a significant development over Hekataios, who had used this term in a strict sense for the groups dwelling in Sindh only."

- ^ Basham, Arthur Llewellyn (1974). The Civilizations of Monsoon Asia. Angus and Robertson. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-207-12687-1.

... that he annexed parts of India as Hindush, the twentieth satrapy of his empire.

- ^ a b Sethna, Kaikhushru Dhunjibhoy (2000). Problems of Ancient India. Aditya Prakashan. p. 127. ISBN 978-81-7742-026-5.

Olmstead's Hindush is the Punjāb east of the Indus - as his first Map, "Satrapies of the Persian Empire ", makes perfectly clear.

- ^ M. A. Dandamaev. "A Political History of the Achaemenid Empire" p 147. BRILL, 1989 ISBN 978-9004091726

- ^ Rafi U. Samad, The Grandeur of Gandhara: The Ancient Civilization of the Swat, Peshawar, Kabul and Indus Valleys. Algora Publishing, 2011, p. 33 ISBN 0875868592

- ^ "Hidus could be the areas of Sindh, or Taxila and West Punjab." in Cambridge Ancient History. Cambridge University Press. 2002. p. 204. ISBN 9780521228046.

- ^ Naqs-e Rostam – Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- ^ Naqs-e Rostam – Encyclopaedia Iranica List of nationalities of the Achaemenid military with corresponding drawings.

- ^ Herodotus VII 64-66

- ^ "A Sindhu contingent formed a part of his army which invaded Greece and stormed the defile at Thermopylae in 480 BC, thus becoming the first ever force from India to fight on the continent of Europe. It, apparently, distinguished itself in battle because it was followed by another contingent which formed a part of the Persian army under Mardonius which lost the battle of Platea"Sandhu, Gurcharn Singh (2000). A military history of ancient India. Vision Books. p. 179. ISBN 9788170943754.

- ^ LacusCurtius • Herodotus — Book IX: Chapters 1‑89. pp. IX-32.

- ^ Tola, Fernando (1986). "India and Greece before Alexander". Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute. 67 (1/4): 165. JSTOR 41693244.

- ^ Magee, Peter; Petrie, Cameron; Knox, Robert; Khan, Farid; Thomas, Ken (October 2005). "The Achaemenid Empire in South Asia and Recent Excavations in Northwest Pakistan". American Journal of Archaeology. 109 (4). University of Chicago: 713. doi:10.3764/aja.109.4.711. JSTOR 40025695. S2CID 54089753.