This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2021) |

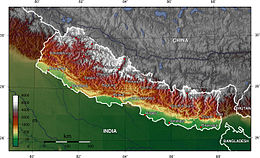

Nepal measures about 880 kilometers (547 mi) along its Himalayan axis by 150 to 250 kilometers (93 to 155 mi) across. It has an area of 147,516 km2 (56,956 sq mi).[1]

| |

| Continent | Asia |

|---|---|

| Region | Southern Asia coordinates = 28°00′N 84°00′E / 28.000°N 84.000°E |

| Area | Ranked 93rd |

| • Total | 147,516 km2 (56,956 sq mi) |

| • Land | 92.94% |

| • Water | 7.06% |

| Coastline | 0 km (0 mi) |

| Borders | Total land borders: 2,926 km (1,818 mi) China (PRC): 1,236 km (768 mi) India: 1,690 km (1,050 mi) |

| Highest point | Mount Everest 8,848 m (29,029 ft) |

| Lowest point | Mukhiyapatti Musharniya 59 m (194 ft) |

| Longest river | Karnali |

| Largest lake | Rara Lake |

Nepal is landlocked by China's Tibet Autonomous Region to the north and India on other three sides. West Bengal's narrow Siliguri Corridor separate Nepal and Bangladesh. To the east are Bhutan and India.

Nepal has a very high degree of geographic diversity and can be divided into three main regions: Terai, Hilly, and Himal. The Terai region, covering 17% of Nepal's area, is a lowland region with some hill ranges and is culturally more similar to parts of India. The Hilly region, encompassing 68% of the country's area, consists of mountainous terrain without snow and is inhabited by various indigenous ethnic groups. The Himal region, covering 15% of Nepal's area, contains snow and is home to several high mountain ranges, including Mount Everest, the world's highest peak. Nepal, with elevations ranging from less than 100 meters to over 8,000 meters, has eight climate zones from tropical to perpetual snow. The majority of the country's population resides in the tropical and subtropical climate zones. The tropical zone, below 1,000 meters, experiences frost less than once per decade and is suitable for growing various fruits and crops. The subtropical climate zone, from 1,000 to 2,000 meters, is the most prevalent and suitable for growing rice, maize, millet, wheat, and other crops. The temperate climate zone, from 2,000 to 3,000 meters, occupies 12% of Nepal's land area and is suitable for cold-tolerant crops. The subalpine, alpine, and nival zones have progressively fewer human settlements and agricultural activities.

Seasons are divided into a wet season from June to September and a dry season from October to June. The summer monsoon can cause flooding and landslides, while the winter monsoon is marked by occasional rainfall and snowfall. The diverse elevation results in various biomes, including tropical savannas, subtropical and temperate forests, montane grasslands, and shrublands.

Nepal has three categories of rivers: the largest systems (Koshi, Gandaki/Narayani, Karnali/Goghra, and Mahakali), second category rivers (rising in the Middle Hills and Lower Himalayan Range), and third category rivers (rising in the outermost Siwalik foothills and mostly seasonal). These rivers can cause serious floods and pose challenges to transportation and communication networks. River management involves addressing flooding, sedimentation, and sustainable water sources for irrigation. Building dams in Nepal is controversial due to seismic activity, glacial lake formation, sedimentation rates, and cross-border equity issues between India and Nepal.

Nepal's land cover is dominated by forests, which cover 39.09% of the country's total geographical area, followed by agriculture areas at 29.83%. The hill region constitutes the largest portion of Nepal, with significant cultivated lands and natural vegetation. Forests in Nepal face deforestation due to over-harvesting of firewood, illegal logging, clearing for agriculture, and infrastructure expansion. As of 2010, 64.8% of the forested area in Nepal is covered by core forests of more than 500 ha in size. Deforestation and degradation are driven by multiple processes, including firewood harvesting, construction, urban expansion, and illegal logging.

Nepal has consistently been ranked as one of the most polluted countries in the world.[2][3][4][5][6][7]

Landform regions

For a country of its size, Nepal has tremendous geographic diversity. It rises from as low as 59 metres (194 ft) elevation in the tropical Terai—the northern rim of the Gangetic Plain, through beyond the perpetual snow line to 90 peaks over 7,000 metres (22,966 ft) including Earth's highest (8,848-metre (29,029 ft) Mount Everest or Sagarmatha). In addition to the continuum from tropical warmth to cold comparable to polar regions, average annual precipitation varies from as little as 160 millimetres (6.3 in) in its narrow proportion of the rainshadow north of the Himalayas to as much as 5,500 millimetres (216.5 in) on windward slopes, the maximum mainly resting on the magnitude of the South Asian monsoon.[8]

Forming south-to-north transects, Nepal can be divided into three belts: Terai, Pahad and Himal. In the other direction, it is divided into three major river systems, east to west: Koshi, Gandaki/Narayani and Karnali (including the Mahakali along the western border), all tributaries of the Ganges river. The Ganges-Yarlung Zangbo/Brahmaputra watershed largely coincides with the Nepal-Tibet border, save for certain tributaries rising beyond it.

Himal

Himal Region is a mountainous region containing snow. The Mountain Region begins where high ridges (Nepali: लेक; lekh) begin substantially rising above 3,000 metres (10,000 ft) into the subalpine and alpine zone which are mainly used for seasonal pasturage. By geographical view, it covers 15% of the total area of Nepal. A few tens kilometers further north the high Himalaya abruptly rise along the Main Central Thrust fault zone above the snow line at 5,000 to 5,500 metres (16,400 to 18,000 ft). Some 90 of Nepal's peaks exceed 7,000 metres (23,000 ft) and eight exceed 8,000 metres (26,247 ft) including Mount Everest at 8,848 metres (29,029 ft) and Kanchenjunga at 8,598 metres (28,209 ft).

There are some 20 subranges including the Kanchenjunga massif along with the Mahalangur Himal around Mount Everest. Langtang north of Kathmandu, Annapurna and Manaslu north of Pokhara, then Dhaulagiri further west with Kanjiroba north of Jumla and finally Gurans Himal in the far west.

| Mountain | Height | Section | Location | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mount Everest (Highest in the world) |

8,848 m | 29,029 ft | Khumbu Mahalangur | Khumbu Pasanglhamu, Solukhumbu District, Province No. 1 (Nepal-China Border) |

| Kangchenjunga (3rd highest in the world) |

8,586 m | 28,169 ft | Northern Kanchenjunga | Phaktanglung / Sirijangha, Taplejung District, Province No. 1 (Nepal-India Border) |

| Lhotse (4th highest in the world) |

8,516 m | 27,940 ft | Everest Group | Khumbu Pasanglhamu, Solukhumbu District, Province No. 1 (Nepal-China Border) |

| Makalu (5th highest in the world) |

8,462 m | 27,762 ft | Makalu Mahalangur | Makalu, Sankhuwasabha District, Province No. 1 (Nepal-China Border) |

| Cho Oyu (6th highest in the world) |

8,201 m | 26,906 ft | Khumbu Mahalangur | Khumbu Pasanglhamu, Solukhumbu District, Province No. 1 (Nepal-China Border) |

| Dhaulagiri (7th highest in the world) |

8,167 m | 26,795 ft | Dhaulagiri | Dhaulagiri, Myagdi District, |

| Manaslu (8th highest in the world) |

8,163 m | 26,759 ft | Mansiri Himal | Tsum Nubri, Gorkha District / Nashong, Manang District, |

| Annapurna (10th highest in the world) |

8,091 m | 26,545 ft | Annapurna Massif | Annapurna, Kaski District / Annapurna, Myagdi District, |

Trans-Himalayan

The main watershed between the Brahmaputra (called Yarlung Tsangpo in Tibet) and the Ganges system (including all of Nepal) actually lies north of the highest ranges. Alpine, often semi-arid valleys—including Humla, Jumla, Dolpo, Mustang, Manang and Khumbu—cut between Himalayan sub ranges or lie north of them.

Some of these valleys historically were more accessible from Tibet than Nepal and are populated by people with Tibetan affinities called Bhotiya or Bhutia including the famous Sherpas in Kumbu valley near Mount Everest. With Chinese cultural hegemony in Tibet itself, these valleys have become repositories of traditional ways. Valleys with better access from the hill regions to the south are culturally linked to Nepal as well as Tibet, notably the Kali Gandaki Gorge where Thakali culture shows influences in both directions.

Permanent villages in the mountain region stand as high as 4,500 metres (15,000 ft) with summer encampments even higher. Bhotiyas graze yaks, grow cold-tolerant crops such as potatoes, barley, buckwheat and millet. They traditionally traded across the mountains, e.g., Tibetan salt for rice from lowlands in Nepal and India. Since trade was restricted in the 1950s they have found work as high altitude porters, guides, cooks and other accessories to tourism and alpinism.[10]

Hilly

Hilly Region is a mountain region which does not generally contain snow. It is situated to the south of the Himal Region (the snowy mountain region). This region begins at the Lower Himalayan Range, where a fault system called the Main Boundary Thrust creates an escarpment 1,000 to 1,500 metres (3,000 to 5,000 ft) high, to a crest between 1,500 and 2,700 metres (5,000 and 9,000 ft). It covers 68% of the total area of Nepal.

These steep southern slopes are nearly uninhabited, thus an effective buffer between languages and culture in the Terai and Hilly. Paharis mainly populate river and stream bottoms that enable rice cultivation and are warm enough for winter/spring crops of wheat and potato. The increasingly urbanized Kathmandu and Pokhara valleys fall within the Hill region. Newars are an indigenous ethnic group with their own Tibeto-Burman language. The Newar were originally indigenous to the Kathmandu valley but have spread into Pokhara and other towns alongside urbanized Pahari.

Other indigenous Janajati ethnic groups -— natively speaking highly localized Tibeto-Burman languages and dialects -— populate hillsides up to about 2,500 metres (8,000 ft). This group includes Magar and Kham Magar west of Pokhara, Gurung south of the Annapurnas, Tamang around the periphery of Kathmandu Valley and Rai, Koinch Sunuwar and Limbu further east. Temperate and subtropical fruits are grown as cash crops. Marijuana was grown and processed into Charas (hashish) until international pressure persuaded the government to outlaw it in 1976. There is increasing reliance on animal husbandry with elevation, using land above 2,000 metres (7,000 ft) for summer grazing and moving herds to lower elevations in winter. Grain production has not kept pace with population growth at elevations above 1,000 metres (3,300 ft) where colder temperatures inhibit double cropping. Food deficits drive emigration out of the Pahad in search of employment.

The Hilly ends where ridges begin substantially rising out of the temperate climate zone into subalpine zone above 3,000 metres (10,000 ft).

Terai

Terai is a low land region containing some hill ranges. Looking out for its coverage, it covers 17% of the total area of Nepal. The Terai (also spelt Tarai) region begins at the Indian border and includes the southernmost part of the flat, intensively farmed Gangetic Plain called the Outer Terai. By the 19th century, timber and other resources were being exported to India. Industrialization based on agricultural products such as jute began in the 1930s and infrastructure such as roadways, railways and electricity were extended across the border before it reached Nepal's Pahad region.

The Outer Terai is culturally more similar to adjacent parts of India's Bihar and Uttar Pradesh than to the Pahad of Nepal. Nepali is taught in schools and often spoken in government offices, however, the local population mostly uses Maithali, Bhojpuri and Tharu languages.

The Outer Terai ends at the base of the first range of foothills called the Chure Hills or Churia. This range has a densely forested skirt of coarse alluvium called the Bhabar. Below the Bhabhar, finer, less permeable sediments force groundwater to the surface in a zone of springs and marshes. In Persian, terai refers to wet or marshy ground. Before the use of DDT this was dangerously malarial. Nepal's rulers used this for a defensive frontier called the char kose jhadi (four kos forest, one kos equaling about three kilometers or two miles).

Above the Bhabar belt, the Chure Hills rise to about 700 metres (2,297 ft) with peaks as high as 1,000 metres (3,281 ft), steeper on their southern flanks because of faults are known as the Main Frontal Thrust. This range is composed of poorly consolidated, coarse sediments that do not retain water or support soil development so there is virtually no agricultural potential and sparse population.

In several places beyond the Chure, there are dūn valleys called Inner Terai. These valleys have productive soil but were dangerously malarial except to indigenous Tharu people who had genetic resistance. In the mid-1950s DDT came into use to suppress mosquitos and the way was open to settlement from the land-poor hills, to the detriment of the Tharu.

The Terai ends and the Pahad begin at a higher range of foothills called the Lower Himalayan Range.

Climate

Altitudinal belts

Nepal's latitude is about the same as that of the United States state of Florida, however with elevations ranging from less than 100 meters (300 ft) to over 8,000 meters (26,000 ft) and precipitation from 160 millimeters (6 in) to over 5,000 millimeters (16 ft) the country has eight climate zones from tropical to perpetual snow.[11]

The tropical zone below 1,000 meters (3,300 ft) experiences frost less than once per decade. It can be subdivided into lower tropical (below 300 meters or 1,000 ft.) with 18% of the nation's land area) and upper (18% of land area) tropical zones. The best mangoes and well as papaya and banana are largely confined to the lower zone. Other fruit such as litchee, jackfruit, citrus and mangoes of lower quality grow in the upper tropical zone as well. Winter crops include grains and vegetables typically grown in temperate climates. The Outer Terai is virtually all in the lower tropical zone. Inner Terai valleys span both tropical zones. The Sivalik Hills are mostly upper tropical. Tropical climate zones extend far upriver valleys across the Middle Hills and even into the Mountain regions.

The subtropical climate zone from 1,000 to 2,000 meters (3,300 to 6,600 ft) occupies 22% of Nepal's land area and is the most prevalent climate of the Middle Hills above river valleys. It experiences frost up to 53 days per year, however, this varies greatly with elevation, proximity to high mountains and terrain either draining or ponding cold air drainage. Crops include rice, maize, millet, wheat, potato, stone fruits and citrus.

The great majority of Nepal's population occupies the tropical and subtropical climate zones. In the Middle Hills, "upper-caste" Hindus are concentrated in tropical valleys which are well suited for rice cultivation while Janajati ethnic groups mostly live above in the subtropical zone and grow other grains more than rice.

The Temperate climate zone from 2,000 to 3,000 meters (6,600 to 9,800 ft) occupies 12% of Nepal's land area and has up to 153 annual days of frost. It is encountered in higher parts of the Middle Hills and throughout much of the Mountain region. Crops include cold-tolerant rice, maize, wheat, barley, potato, apple, walnut, peach, various cole, amaranthus and buckwheat.

The Subalpine zone from 3,000 to 4,000 meters (9,800 to 13,100 ft) occupies 9% of Nepal's land area, mainly in the Mountain and Himalayan regions. It has permanent settlements in the Himalaya, but further south it is only seasonally occupied as pasture for sheep, goats, yak and hybrids in warmer months. There are up to 229 annual days of frost here. Crops include barley, potato, cabbage, cauliflower, amaranthus, buckwheat and apple. Medicinal plants are also gathered.

The Alpine zone from 4,000 to 5,000 meters (13,100 to 16,400 ft) occupies 8% of the country's land area. There are a few permanent settlements above 4,000 meters. There is virtually no plant cultivation although medicinal herbs are gathered. Sheep, goats, yaks and hybrids are pastured in warmer months.

Above 5,000 meters the climate becomes Nival and there is no human habitation or even seasonal use.

Arid and semi-arid land in the rainshadow of high ranges have a Transhimalayan climate. Population density is very low. Cultivation and husbandry conform to subalpine and alpine patterns but depend on snowmelt and streams for irrigation.

Precipitation generally decreases from east to west with increasing distance from the Bay of Bengal, source of the summer monsoon. Eastern Nepal gets about 2,500 mm (100 in) annually; the Kathmandu area about 1,400 mm (55 in) and western Nepal about 1,000 mm (40 in). This pattern is modified by adiabatic effects as rising air masses cool and drop their moisture content on windward slopes, then warm up as they descend so relative humidity drops. Annual precipitation reaches 5,500 mm (18 ft) on windward slopes in the Annapurna Himalaya beyond a relatively low stretch of the Lower Himalayan Range. In rainshadows beyond the high mountains, annual precipitation drops as low as 160 mm (6 in).

Seasons

The year is divided into a wet season from June to September—as summer warmth over Inner Asia creates a low-pressure zone that draws in moist air from the Indian Ocean—and a dry season from October to June as cold temperatures in the vast interior create a high-pressure zone causing dry air to flow outward. April and May are months of intense water stress when cumulative effects of the long dry season are exacerbated by temperatures rising over 40 °C (104 °F) in the tropical climate belt. Seasonal drought further intensifies in the Siwaliks hills consisting of poorly consolidated, coarse, permeable sediments that do not retain water, so hillsides are often covered with drought-tolerant scrub forest. In fact, much of Nepal's native vegetation adapted to withstand drought, but less so at higher elevations where cooler temperatures mean less water stress.

The summer monsoon may be preceded by a buildup of thunderstorm activity that provides water for rice seedbeds. Sustained rain on average arrives in mid-June as rising temperatures over Inner Asia creates a low-pressure zone that draws in moist air from the Indian Ocean, but this can vary up to a month. Significant failure of monsoon rains historically meant drought and famine while above-normal rains still cause flooding and landslides with losses in human lives, farmland and buildings.

The monsoon also complicates transportation with roads and trails washing out while unpaved roads and airstrips may become unusable and cloud cover reduces safety margins for aviation. Rains diminish in September and generally end by mid-October, ushering in generally cool, clear, and dry weather, as well as the most relaxed and jovial period in Nepal. By this time, the harvest is completed and people are in a festive mood. The two largest and most important Hindu festivals—Dashain and Tihar (Dipawali)—arrive during this period, about one month apart. The post-monsoon season lasts until about December.

After the post-monsoon comes the winter monsoon, a strong northeasterly flow marked by occasional, short rainfalls in the lowlands and plains and snowfalls in the high-altitude areas. In this season the Himalayas function as a barrier to cold air masses from Inner Asia, so southern Nepal and northern India have warmer winters than would otherwise be the case. April and May are dry and hot, especially below 1,200 meters (4,000 ft) where afternoon temperatures may exceed 40 °C (104 °F).

Environment

The dramatic changes in elevation along this transect result in a variety of biomes, from tropical savannas along the Indian border, to subtropical broadleaf and coniferous forests in the hills, to temperate broadleaf and coniferous forests on the slopes of the Himalaya, to montane grasslands and shrublands, and finally rock and ice at the highest elevations.

This corresponds to the Terai-Duar savanna and grasslands ecoregion.

Subtropical forests dominate the lower elevations of the Hill region. They form a mosaic running east–west across Nepal, with Himalayan subtropical broadleaf forests between 500 and 1,000 meters (1,600 and 3,300 ft) and Himalayan subtropical pine forests between 1,000 and 2,000 meters (3,300 and 6,600 ft). At higher elevations, to 3,000 meters (10,000 ft), are found temperate broadleaf forests: eastern Himalayan broadleaf forests to the east of the Gandaki River and western Himalayan broadleaf forests to the west.

The native forests of the Mountain region change from east to west as precipitation decreases. They can be broadly classified by their relation to the Gandaki River. From 3,000 to 4,000 meters (10,000 to 13,000 ft) are the eastern and western Himalayan subalpine conifer forests. To 5,500 meters (18,000 ft) are the eastern and western Himalayan alpine shrub and meadows.

Environmental issues

- Natural hazards

- Earthquakes, severe thunderstorms (tornadoes are rare[12]), flooding and flash flooding, landslides, drought, and famine depending on the timing, intensity, and duration of the summer monsoons

- Environment - current issues

- Deforestation (overuse of wood for fuel and lack of alternatives); contaminated water (with human and animal wastes, agricultural runoff, and industrial effluents); wildlife conservation; vehicular emissions

- Environment - international agreements

-

- Party to: Biodiversity, Climate Change, Climate Change-Kyoto Protocol, Desertification, Endangered Species, Hazardous Wastes, Law of the Sea, Ozone Layer Protection, Tropical Timber 83, Tropical Timber 94, Wetlands

- Signed, but not ratified: Marine Life Conservation

- Existing and proposed dams, barrages and canals for flood control, irrigation and hydroelectric generation

River systems

Nepal has three categories of rivers. The largest systems -— from east to west the Koshi, Gandaki/Narayani, Karnali/Goghra and Mahakali—originate in multiple tributaries rising in or beyond the high Himalaya that maintain substantial flows from snowmelt through the hot, drought-stricken spring before the summer monsoon. These tributaries cross the highest mountains in deep gorges, flow south through the Middle Hills, then join in candelabra-like configuration before crossing the Lower Himalayan Range and emerging onto the plains where they have deposited megafans exceeding 10,000 km2 (4,000 sq mi) in area.

The Koshi is also called Sapta Koshi for its seven Himalayan tributaries in eastern Nepal: Indrawati, Sun Koshi, Tama Koshi, Dudh Koshi, Liku, Arun, and Tamor. The Arun rises in Tibet some 150 kilometers (100 mi) beyond Nepal's northern border. A tributary of the Sun Koshi, Bhote Koshi also rises in Tibet and is followed by the Arniko Highway connecting Kathmandu and Lhasa.

The Gandaki/Narayani has seven Himalayan tributaries in the center of the country: Daraundi, Seti Gandaki, Madi, Kali, Marsyandi, Budhi, and Trisuli also called Sapta Gandaki. The Kali Gandaki rises on the edge of the Tibetan Plateau and flows through the semi-independent Kingdom of Mustang, then between the 8,000 meter Dhaulagiri and Annapurna ranges in the world's deepest valley. The Trisuli rises north of the international border inside Tibet. After the seven upper tributaries join, the river becomes the Narayani inside Nepal and is joined by the East Rapti from Chitwan Valley. Crossing into India, its name changes to Gandak.

The Karnali drains western Nepal, with the Bheri and Seti as major tributaries. The upper Bheri drains Dolpo, a remote valley beyond the Dhaulagiri Himalaya with traditional Tibetan cultural affinities. The upper Karnali rises inside Tibet near-sacred Lake Manasarovar and Mount Kailash. The area around these features is the hydrographic nexus of South Asia since it holds the sources of the Indus and its major tributary the Sutlej, the Karnali—a Ganges tributary—and the Yarlung Tsangpo/Brahmaputra. It is the centre of the universe according to traditional cosmography. The Mahakali or Kali along the Nepal-India border on the west joins the Karnali in India, where the river is known as Goghra or Ghaghara.

Second category rivers rise in the Middle Hills and Lower Himalayan Range, from east to west the Mechi, Kankai and Kamala south of the Kosi; the Bagmati that drains Kathmandu Valley between the Kosi and Gandaki systems, then the West Rapti and the Babai between the Gandaki and Karnali systems. Without glacial sources, annual flow regimes in these rivers are more variable although limited flow persists through the dry season.

Third category rivers rise in the outermost Siwalik foothills and are mostly seasonal.

None of these river systems supports significant commercial navigation. Instead, deep gorges create obstacles to establishing transport and communication networks and de-fragmenting the economy. Foot-trails are still the primary transportation routes in many hill districts.

River management

Rivers in all three categories are capable of causing serious floods. Koshi River in the first category caused a major flood in August 2008 in Bihar state, India after breaking through a poorly maintained embankment just inside Nepal. The West Rapti in the second category is called "Gorakhpur's Sorrow" for its history of urban flooding. Third category Terai rivers are associated with flash floods.[13]

Since uplift and erosion are more or less in equilibrium in the Himalaya, at least where the climate is humid,[14] rapid uplift must be balanced out by annual increments of millions tonnes of sediments washing down from the mountains; then on the plains settling out of suspension on vast alluvial fans over which rivers meander and change course at least every few decades, causing some experts to question whether manmade embankments can contain the problem of flooding.[15] Traditional Mithila culture along the lower Koshi in Nepal and Bihar celebrated the river as the giver of life for its fertile alluvial soil, yet also the taker of life through its catastrophic floods.[16]

Large reservoirs in the Middle Hills may be able to capture peak flows and mitigate downstream flooding, to store surplus monsoon flows for dry season irrigation and to generate electricity. Water for irrigation is especially compelling because the Indian Terai is suspected to have entered a food bubble where dry season crops are dependent on water from tube wells that in the aggregate are unsustainably "mining" groundwater. [17]

Depletion of aquifers without building upstream dams as a sustainable alternative water source could precipitate a Malthusian catastrophe in India's food insecure states Uttar Pradesh[citation needed] and Bihar,[18] with over 300 million combined population. With India already experiencing a Naxalite–Maoist insurgency[19] in Bihar, Jharkhand and Andhra Pradesh, Nepalese reluctance to agree to water projects could even seem an existential threat to India.[20]

As Nepal builds barrages to divert more water for irrigation during the dry season preceding the summer monsoon, there is less for downstream users in Bangladesh and India's Bihar and Uttar Pradesh states. The best solution could be building large upstream reservoirs, to capture and store surplus flows during the summer monsoon as well as providing flood control benefits to Bangladesh and India. Then water-sharing agreements could allocate a portion of the stored water to be left to flow into India during the following dry season.

Nevertheless, building dams in Nepal is controversial for several reasons. First, the region is seismically active. Dam failures caused by earthquakes could cause tremendous death and destruction downstream, particularly on the densely populated Gangetic Plain.[21] Second, global warming has led to the formation of glacial lakes dammed by unstable moraines. Sudden failures of these moraines can cause floods with cascading failures of manmade structures downstream.[22]

Third, sedimentation rates in the Himalaya are extremely high, leading to rapid loss of storage capacity as sediments accumulate behind dams.[23] Fourth, there are complicated questions of cross-border equity in how India and Nepal would share costs and benefits that have proven difficult to resolve in the context of frequent acrimony between the two countries.[20]

Area

- Total: 147,516 km2 (56,956 sq mi)

- Land: 143,181 km2 (55,282 sq mi)

- Water: 4,000 km2 (1,544 sq mi)

- Coastline

- 0 km (landlocked)

- Elevation extremes

-

- Lowest point: Kechana Kawal, jhapa district 59 m

- Highest point: Sagarmatha (Mount Everest) 8,848 m

Resources and land use

- Natural resources

- Quartz, water, timber, hydropower, scenic beauty, small deposits of lignite, copper, cobalt, iron ore

- Land use

-

- Arable land: 16.0%

- Permanent crops: 0.8%

- Other: 83.2% (2001)

- Irrigated land

- 11,680 km² (2003) Nearly 50% of arable land

- Total renewable water resources

- 210.2 km3 (2011)

Land cover

ICIMOD’s first and most complete national land cover[24] database of Nepal prepared using public domain Landsat TM data of 2010 shows that show that forest is the dominant form of land cover in Nepal covering 57,538 km2 with a contribution of 39.09% to the total geographical area of the country. Most of this forest cover is broadleaved closed and open forest, which covers 21,200 km2 or 14.4% of the geographical area.

Needleleaved open forest is the least common of the forest areas covering 8267 km2 (5.62%). Agriculture area is significant extending over 43,910 km2 (29.83%). As would be expected, the high mountain area is largely covered by snow and glaciers and barren land.

The Hill region constitutes the largest portion of Nepal, covering 29.5% of the geographical area, and has a large area (19,783 km2) of cultivated or managed lands, natural and semi natural vegetation (22,621 km2) and artificial surfaces (200 km2). The Tarai region has more cultivated or managed land (14,104 km2) and comparatively less natural and semi natural vegetation (4280 km2). The Tarai has only 267 km2 of natural water bodies. The High mountain region has 12,062 km2 of natural water bodies, snow/glaciers and 13,105 km2 barren areas.

Forests

25.4% of Nepal's land area, or about 36,360 km2 (14,039 sq mi) is covered with forest according to FAO figures from 2005. FAO estimates that around 9.6% of Nepal's forest cover consists of primary forest which is relatively intact. About 12.1% Nepal's forest is classified as protected while about 21.4% is conserved according to FAO. About 5.1% Nepal's forests are classified as production forest. Between 2000 and 2005, Nepal lost about 2,640 km2 (1,019 sq mi) of forest. Nepal's 2000–2005 total deforestation rate was about 1.4% per year meaning it lost an average of 530 km2 (205 sq mi) of forest annually. Nepal's total deforestation rate from 1990 to 2000 was 920 km2 (355 sq mi) or 2.1% per year. The 2000–2005 true deforestation rate in Nepal, defined as the loss of primary forest, is −0.4% or 70 km2 (27 sq mi) per year. Forest is not changing in the plan land of Nepal, forest fragmenting on the "Roof of the World".[25]

According to ICIMOD figures from 2010, forest is the dominant form of land cover in Nepal covering 57,538 km2 with a contribution of 39.09% to the total geographical area of the country.[26] Most of this forest cover is broadleaved closed and open forest, which covers 21,200 km2 or 14.4% of the geographical area. Needleleaved open forest is the least common of the forest areas covering 8,267 km2 (5.62%). At national level 64.8% area is covered by core forests of > 500 ha size and 23.8% forests belong to patch and edge category forests. The patch forest constituted 748 km2 at national level, out of which 494 km2 of patch forests are present in hill regions. Middle mountains, Siwaliks and Terai regions have more than 70% of the forest area under core forest category > 500 ha size. The edge forests constituted around 30% of forest area of High Mountain and Hill regions.[26] Forest Resource Assessment (FRA) which was conducted between 2010 and 2014 by the Ministry of Forest and Soil conservation with the financial and technical help of the Government of Finland shows that 40.36% of the land of Nepal is forested. 4.40% of the land has shrubs and bushes.

Deforestation is driven by multiple processes.[27] Virtually throughout the nation, over-harvest of firewood remains problematic. Despite the availability of liquefied petroleum gas in towns and cities, firewood is sold more at energy-competitive prices because cutting and selling it is a fallback when better employment opportunities aren't forthcoming. Firewood still supplies 80% of Nepal's energy for heating and cooking. Harvesting construction timber and lopping branches for fodder for cattle and other farm animals are also deforestation/degradation drivers in all geographic zones.

Illegal logging is a problem in the Siwaliks, with sawlogs smuggled into India.[28] Clearing for resettlement and agriculture expansion also causes deforestation as does urban expansion, building infrastructure such as schools, hospitals, electric transmission lines, water tanks, police and army barracks, temples and picnic areas.

In the Middle Hills road construction, reservoirs, transmission lines and extractive manufacturing such as cement factories cause deforestation. In the mountains building hotels, monasteries and trekking trails cause deforestation while timber-smuggling into the Tibet Autonomous Region and over-grazing cause degradation.

Boundaries

Border crossings with India

While India and Nepal have an open border with no restrictions on movement of their citizens on either side, there are 23 checkpoints for trade purposes. These are listed in clockwise order, east to west. The six in italics are also used for entry/exit by third country nationals.[29]

Border crossings with China

See also

References

- ^ "Government unveils new political map including Kalapani, Lipulekh and Limpiyadhura inside Nepal borders". kathmandupost.com. Archived from the original on 7 January 2024. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- ^ "Nepal's holy Bagmati River choked with black sewage, trash". Associated Press. 17 August 2022. Archived from the original on 12 July 2023. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ "One more report ranks Nepal among most polluted countries in the world". Archived from the original on 8 July 2023. Retrieved 8 July 2023.

- ^ "Accra, Ghana". Archived from the original on 8 July 2023. Retrieved 8 July 2023.

- ^ "Averting an air pollution disaster in South Asia". 21 April 2023. Archived from the original on 8 July 2023. Retrieved 8 July 2023.

- ^ "Trash and Overcrowding at the Top of the World". Archived from the original on 8 July 2023. Retrieved 8 July 2023.

- ^ "The very air we breathe | UNICEF Nepal". Archived from the original on 8 July 2023. Retrieved 8 July 2023.

- ^ Dahal[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Peaks of Nepal". Travel Guide. Himalayan Echo Trek and Travel. Archived from the original on 7 June 2019. Retrieved 13 December 2014.

- ^ Graafen, Rainer; Seeber, Christian (June 1992). Important Trade Routes in Nepal and Their Importance to the Settlement Process (PDF). Vol. 130. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 April 2021. Retrieved 22 September 2020.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ The Map of Potential Vegetation of Nepal - a forestry/agroecological/biodiversity classification system (PDF), Forest & Landscape Development and Environment Series 2-2005 and CFC-TIS Document Series No.110., 2005, ISBN 87-7903-210-9, archived from the original (PDF) on 3 December 2013, retrieved 22 November 2013

- ^ Mallapaty, Smriti (12 April 2019). "Nepali scientists record country's first tornado: The team confirmed the rare event using satellite images, social-media posts and a visit to the affected area". Nature News. Spring Nature Publishing. Archived from the original on 17 April 2019. Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- ^ Aryal, Ravi Sharma; Rajkarnikar, Gautam (2011). Water Resources of Nepal in the Context of Climate Change (PDF). Kathmandu: Government of Nepal, Water and Energy Commission Secretariat. p. vii. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 January 2016. Retrieved 9 December 2013.

- ^ Hack, John T. (1960). "Interpretation of Erosional Topography in Humid Temperate Regions" (PDF). American Journal of Science. 258-A: 80–97. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 April 2012. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- ^ Devkota, Lochan; Crosato, Alessandra; Giri, Sanjay (2012). "Effect of the barrage and embankments on flooding and channel avulsion, case study Koshi River, Nepal". Rural Infrastructure. 3 (3): 124–132. Retrieved 9 December 2013.

- ^ Thakur, Atul Kumar (7 May 2009). "Floods of Mithila Region: Raising Questions on Survival". Standpoint. Archived from the original on 18 December 2013. Retrieved 9 December 2013.

- ^ Brown, Lester R. (29 November 2013). "India's dangerous 'food bubble'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 18 December 2013. Retrieved 10 December 2013. Alt URL Archived 16 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The United Nations. World Food Programme (2009). Food Security Atlas of Rural Bihar (PDF). New Delhi: Institute for Human Development. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 December 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ^ Kennedy, Kristian A. (17 May 2010). "The Naxalite Insurgency in India". Geopolitical Monitor. Archived from the original on 15 December 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ^ a b Malhotra, Pia (July 2010). "Water Issues between Nepal, India & Bangladesh, a Review of Literature" (PDF). IPCS Special Report No. 95. New Delhi: Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies: 11. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 November 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ^ Thapa, A.B. (January 2010). "Revision of the West Seti Dam Design in Nepal". Hydro Nepal (6). Kathmandu. Archived from the original on 14 December 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ^ ICIMOD (2011). "Glacial Lakes and Glacial Lake Outburst Floods in Nepal" (PDF). Kathmandu: International Center for Integrated Mountain Development. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 January 2014. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Choden, Sonam (2009). "Sediment Transport Studies in Punatsangchu River, Bhutan". Lund, Sweden: Lund University, Water Resources Engineering. Archived from the original on 15 December 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Uddin, Kabir; Shrestha, Him Lal; Murthy, M. S. R.; Bajracharya, Birendra; Shrestha, Basanta; Gilani, Hammad; Pradhan, Sudip; Dangol, Bikash (15 January 2015). "Development of 2010 national land cover database for the Nepal". Journal of Environmental Management. Land Cover/Land Use Change (LC/LUC) and Environmental Impacts in South Asia. 148: 82–90. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2014.07.047. PMID 25181944.

- ^ Uddin, Kabir; Chaudhary, Sunita; Chettri, Nakul; Kotru, Rajan; Murthy, Manchiraju; Chaudhary, Ram Prasad; Ning, Wu; Shrestha, Sahas Man; Gautam, Shree Krishna (September 2015). "The changing land cover and fragmenting forest on the Roof of the World: A case study in Nepal's Kailash Sacred Landscape". Landscape and Urban Planning. 141: 1–10. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2015.04.003.

- ^ a b Uddin, Kabir; Shrestha, Him Lal; Murthy, M. S. R.; Bajracharya, Birendra; Shrestha, Basanta; Gilani, Hammad; Pradhan, Sudip; Dangol, Bikash (15 January 2015). "Development of 2010 national land cover database for the Nepal". Journal of Environmental Management. Land Cover/Land Use Change (LC/LUC) and Environmental Impacts in South Asia. 148: 82–90. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2014.07.047. PMID 25181944.

- ^ Kathmandu Forestry College (2013). Chitwan-Annapurna Landscape Drivers of Deforestation and Forest Degradation (PDF). Kathmandu: World Wildlife Fund Nepal, Hariyo Ban Program. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ^ Khadka, Navin Singh (28 September 2010). "Nepal's forests 'being stripped by Indian timber demand'". London: British Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 13 October 2018. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ^ "Nepal-India Open Border: Prospects, Problems and Challenges". Nepal Democracy. Archived from the original on 18 October 2005. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ^ a b "中华人民共和国政府和尼泊尔政府关于边境口岸及其管理制度的协定" [China-Nepal Agreement on Port of Entry] (in Chinese). Chinese Embassy in Nepal. 14 January 2012. Archived from the original on 19 October 2020. Retrieved 10 February 2017.

- ^ "News from China" (PDF). Chinese Embassy in India. Vol. XXVIII, no. 7. July 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 July 2019. Retrieved 15 February 2017.

- ^ "Kodari Checkpoint To Open Today". The Spotlight Online. 29 May 2019. Archived from the original on 19 October 2020. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

External links

- This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Nepal and Bhutan : country studies. Federal Research Division.

- This article incorporates public domain material from The World Factbook (2024 ed.). CIA. (Archived 2005 edition.)

- Atlas of Nepal Archived 11 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- Nepal Encyclopedia Geopolitical category Archived 14 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Brief and Concise Geography of Nepal Archived 25 September 2022 at the Wayback Machine