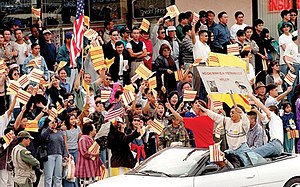

The Hi-Tek incident,[a] referred to in Vietnamese-language media as the Trần Trường incident (Vietnamese: Vụ Trần Trường or Sự kiện Trần Trường), was a series of protests in 1999 by Vietnamese Americans in Little Saigon, Orange County, California in response to Trần Văn Trường's display of the flag of communist Vietnam and a picture of Ho Chi Minh in the window of Hi-Tek Video, a video store that he owned. Occurring amidst the backdrop of the restoration of relations between the two countries and continuous anti-communist activities, some violent, undertaken through the past two decades, it has been considered the largest such protest in the history of Little Saigon.

| Hi-Tek incident | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Protesters on Bolsa Avenue | |||

| Date | January 17 – March 11, 1999 | ||

| Location | |||

| Caused by | Display of the flag of Vietnam and a photo of Ho Chi Minh at Hi-Tek Video | ||

| Goals |

| ||

| Methods | Demonstrations outside the store, sit-ins, candlelight vigils | ||

| Resulted in | Store closed due to eviction and charges of video piracy | ||

| Parties | |||

| |||

| Number | |||

| |||

| Casualties | |||

| Detained | 52 protesters | ||

The protests took place over 53 days, starting on January 17, when the flag and picture were first hung. Over the following two months, hundreds of people gathered daily to protest in front of the shop and called on Trường to remove these symbols, which the community, consisting mostly of anti-communist refugees from South Vietnam and their descendants, found very offensive. The conflict reached its climax on the evening of February 26, when about 15,000 people gathered for a candlelight vigil to protest the human rights situation in Vietnam. The event ended on March 11 when the store closed under threat of eviction and video piracy charges, with Trường being sentenced for the latter five months later.

The demonstrations were considered unique at the time due to their large scale and unlikely participants, with the presence of various demographic groups and more "moderate" voices creating a sense of increased unity among the Vietnamese American community. On the other hand, there were controversies over the disturbances brought on by the protests as well as the cost and manner of police deployment, concerns that Trường's right to freedom of speech was violated, and questions about assimilation and inter-community relations. The event was later regarded as an important turning point in the history of Little Saigon, inspiring many Vietnamese Americans to become more involved in political and civic matters.

Background

editAfter the fall of Saigon in 1975, the United States received an influx of refugees from South Vietnam.[1] By the 1990s, a majority of the refugees and their descendants had settled in Orange County, California, where the Vietnamese community grew from 72,000 in 1990 to 220,000 in 1999.[2] As many of them had fled from the communist government that took over after the defeat of South Vietnam and had witnessed or been a victim of persecution by said government, the community as a whole was virulently anti-communist.[1] Vietnamese Americans who expressed a desire to restore ties with the current state of Vietnam were often pushed away and exiled by the rest of the community.[3] These tensions burst into violence in the 1980s as peace activists and journalists were assassinated and others were assaulted or harassed throughout the decade for expressing supposed pro-communist sympathies or encouraging dialogue with Vietnam, which the FBI has suspected to be the work of a paramilitary group that aimed to overthrow the communist government in Hanoi.[4] The violence subsided later in the decade after the dissolution of this group, but in the 1990s, as Vietnamese American communities became more established in the United States, protests became common to fight off any suspected communist influence, with Orange County becoming the center of political expression.[5] These attitudes also extended to symbols; Vietnamese Americans often use the flag of South Vietnam, also known as the "Vietnamese Heritage and Freedom Flag" or simply the "gold banner" (cờ vàng), as a symbol of their homeland and against communism. On the other hand, the current symbols used by Vietnam have been shunned by the community and are even seen as traumatic.[6]

Trần Văn Trường[b] was one of the "boat people" who fled Vietnam in 1980 after members of his family were killed during the war or sent to re-education camps.[7] As a 20-year-old with no high school education, he joined the Vô Vi Friendship Association (Vietnamese: Hội Ái Hữu Vô Vi), a meditation group, and was noticed by its spiritual leader Ong Tam as "the chosen one", which Trường reportedly responded to by declaring himself God. He left the group in 1989, after other members accused him of trying to take over after the death of Tam, and married his only supporter; ten years later, he claimed he only left to lead a simpler life.[8] Trường then moved to California with his wife and two children, where she was the breadwinner as a computer programmer while he salvaged TVs and VCRs. Eventually, he opened Hi-Tek Video, a video cassette and TV rental store, in 1996 after attending electronics classes. Meanwhile, he had taken trips to Vietnam, where his observations of better living conditions spurred him to advocate for the United States to improve bilateral relations.[9]

Throughout the 1990s, the United States and Vietnam had been making progress in normalizing relations after a two-decade freeze, which led to hot debate in the Vietnamese American community and a peak in protest activity.[10] In 1994, the United States lifted its trade embargo, and a number of Vietnamese Americans began exploring business opportunities between the two countries, with the stagnation of the "underground" economy to supply items to Vietnamese family members during the blockade also leading to attempts to replace it with increased economic ties. However, many members of the community opposed these developments, and when the Vietnamese Chamber of Commerce in Westminster announced it would send a delegation to Vietnam led by its president Dr. Phạm Cơ to look at establishing economic ties, protests soon commenced, with demonstrators picketing Cơ's office before and after the trip and a thousand people gathering in Washington D.C. during the trip. During a protest in Orange County, Trường handed out leaflets for a forum that he organized to start a discussion between the pro- and anti-Hanoi sides and support increased trade with Vietnam, but no one attended.[11] He attempted to foster more discourse on the issue by publishing a series of newsletters on the subject over the next five years, but was largely ignored. Finally, in 1999, Trường decided to put up a picture of Ho Chi Minh, the founder of the Communist Party of Vietnam, and the flag of the current state of Vietnam in Hi-Tek Video to provoke a response from the community; he had already hung said flag on an intermittent basis from 1996 onward but got no reaction. He announced his intentions in two faxes a week in advance, asking for a "dialogue" but also stating "I defy you all... if you dare to come to take them off".[12] The police also said that Trường told them "he did it because he could and because he wanted to antagonize neighboring businesses he was unhappy with".[13]

Events

editAs scheduled, Trường started executing his plan on January 17, 1999 (timed around Martin Luther King Jr. Day and, more controversially, Tết[14]), with only the picture of Ho Chi Minh being displayed. With the store located on Bolsa Avenue, which has been described as the center of Little Saigon, a visitor noticed the picture the same day and contacted others, leading to about 50 people gathering at the store and an employee pulling down the display. The next day, however, Trường put the picture of Ho Chi Minh up again and also displayed a Vietnamese flag, causing another demonstration that swelled to 350 protesters by the middle of the day. After closing early due to the picketing, a protester hit Trường on the head, and he was hospitalized for minor injuries.[15]

Following these initial events, protests continued over 52 consecutive days, with up to 15,000 protesters gathering in front of the store on weekends.[16] The protests were mostly peaceful, with demonstrators shouting anti-communist slogans, holding signs and the flag of South Vietnam, stamping on and burning effigies of Ho Chi Minh, and sharing their stories of repression. There were three broad generational groups at the protests: the older Vietnamese refugees, youth groups who focused more on human rights issues in Vietnam, and a "middle generation" of white collar professionals in their 20s and 30s who used their English skills and assimilation in American society to represent the protesters to the press, police and state politicians.[17] Outside the store, the larger Vietnamese American community showed their solidarity, with shopping centers in Little Saigon raising American and South Vietnamese flags to profess their loyalties and show their anti-communist stance and other demonstrations being held simultaneously in San Jose, New Orleans, and Houston.[18] Vietnam war veterans and people from other ethnicities with strong anti-Communist sentiment such as Cuban Americans, Cambodian Americans and Filipino Americans joined in the protests.[18]

On January 20, Trường's landlord sued for the removal of the display on the basis that it caused a "public nuisance" and thus violated the leasing agreement, and a temporary injunction was granted ordering the display's removal, to the celebration of protesters. However, this was strongly opposed by civil rights activists such as the American Civil Liberties Union, who backed Trường and countersued, leading to a ruling on February 10 that he could keep displaying the images.[19]

The police escorted Trường back into the store on February 20 so he could safely hang the images again; it was later revealed that they had also found evidence of video piracy while inside the building. Trường and his family would face limited but increased violence over the next few days. This was followed on February 26 by the largest rally held during the protests, with 15,000 gathered in a "flashlight vigil" focusing on human rights in Vietnam. Trường was egged on March 1. Five days afterward, the police raided Hi-Tek Video, seizing thousands of tapes and hundreds of VCRs while looking for evidence of a break-in. A police spokesman stated that they had found an "elaborate video counterfeiting operation" inside the store.[17] On March 8, Trường's lawyer stated that he could not reopen the business, and on March 11 the store was closed, with the landlord removing its sign and the display, bringing an end to the demonstrations.[17]

Reactions

editIn response to the protests, Trường initially stated that he had no regrets. He declared that he was not a communist and did not support their rule of Vietnam, but believed in making peace with them and was simply exercising his right to free speech. He also claimed that the piracy charges were meant to target him and that "they should arrest all the other [video store owners] in Little Saigon because everyone does the same thing".[20] The next year, he expressed regret on hanging the flag, but continued to be frustrated by the protesters, saying "They want to hit me, they want to kill me because... I showed the flag. That is not... freedom. There is no freedom to say what you like in the Vietnamese community. I was trying [to] debate and talk with them and show the freedom here. But they acted here like the Communists do in Vietnam."[21]

The Vietnamese community in the United States were outraged by the display, describing the use of communist symbols as bringing back the trauma of repression, war, and fleeing Vietnam, and most supported the protests.[22] These actions were also marked by a high rate of youth participation, which was spurred on by student groups retaliating to a Los Angeles Times column from Daniel C. Tsang claiming that most of the younger generation had become apolitical and were not as anti-communist as their elders.[c][23] With information on the events spreading quickly through the community via the Internet and a well-established system of Vietnamese-language radio stations, solidarity protests were organized in other cities with high concentrations of Vietnamese Americans, such as San Jose, New Orleans, and Houston. Also Vietnam War veterans and people from other ethnicities with high anti-Communist sentiment like Filipino Americans, Cambodian Americans, and Cuban Americans joined in. In addition to the base issue of Trường's display, protesters also aimed to make a statement on the human rights situation in Vietnam and enhance Vietnamese American political power. This set of protests were marked by increased participation from new groups, including the aforementioned youth, first-time protestors and those with a more "moderate" stance that still wanted to do business with Vietnam.[24] The diversity of protestors led to an increased sense of unity among different groups in the community; other than age, demonstrators came from diverse backgrounds in regard to class, faith, region and gender. During the demonstrations, community leaders who had previously tussled with each other shook hands and inter-religious prayer services were offered.[25]

Other Americans looked upon the protests with more mixed reactions, and while some Vietnam veterans attended demonstrations, most of "mainstream society" tended to focus more on free speech concerns. Nam Q. Ha, a scholar at Rice University, analyzed two different comments and took note of how both the expression of support and opposition to the protests from other Americans tended to show "nativist sentiment", characterizing Vietnamese Americans as not understanding the United States.[26] Another scholar, Phuong Nguyen, came to a similar, critical conclusion on the coverage of the events by the mainstream media and instead argued that, if looked at through a transnational perspective, the protesters were instead emphasizing the American way and their Americanness by their demonstrations.[27] In contrast, David Meyer and Như-Ngọc T. Ông stated in an article for the Journal of Vietnamese Studies that it was an example of how early Vietnamese American political activism focused on the Vietnamese government, either directly or against local issues that were ultimately "proxies", rather than domestic American politics.[28] Civil rights activists particularly disapproved of the protests, with the American Civil Liberties Union providing Trường and his attorney legal support and stating that using the "public nuisance" argument against him would create a "dangerous precedent". While Los Angeles Times columnist Dana Parsons was less enthusiastic about Trường and was suspicious of his motives, he still supported Trường and felt that the protesters were hypocritical for attempting to restrict his freedom of expression while having fled and protested human rights abuses in Vietnam, a criticism also shared by the ACLU.[29] On March 3, Orange County Republican Party leader Tom Fuentes announced that the party would back the protests and send personnel to participate in demonstrations, which the Los Angeles Times described as the first mainstream political support for the protestors.[30]

Officials in Westminster were also divided. Some members of the city council disapproved of the protests and issued similar nativist attitudes to other residents, while others supported and participated in the demonstrations. Tony Lâm, the only Vietnamese American on the city council at the time, decided not to join the protests on the advice of city attorneys, which led to significant disapproval from the community.[22] The costs of the protests were another factor, as the city had to mobilize 200 police officers equipped with riot gear to protect Trường and made 52 arrests at a cost of over $750,000.[31] This led to heavy criticism of the local police force, with Chief of Police James Cook being questioned by the police union over his wavering tactics and Trường's attorneys announcing their intention to sue the police force for not adequately protecting him. These controversies were also compounded by slurs and an order to fire indiscriminately into the crowd being broadcast over police frequencies, although it was later determined that it was probably an unaffiliated ham radio operator because of earlier racist broadcast incidents on amateur radio bands.[32]

The Vietnamese government issued multiple statements in support of Trường, with the embassy in Washington D.C. expressing concern for his safety and "exercise of his rights" and the San Francisco consulate phoning him to assure their support.[33] It was widely rumored that Trường was directly backed by the government of Vietnam, with some Vietnamese Americans fearing a "Communist takeover" of their community.[34] One example was a specific allegation that a $50 arrival fee was leveraged on passengers to fund him at Hanoi's Noi Bai International Airport, which was denied by Trường as well as staff at the Vietnamese consulate in San Francisco.[35]

Aftermath and long-term developments

editConcurrent demonstrations were held in front of Councilman Lam's restaurant as his lack of support for the original protests led to accusations that he himself was a communist sympathizer, and a recall campaign was initiated against him. After attempting to sue for financial losses and emotional pain, he ultimately relented, closed his restaurant and withdrew from politics in 2002, having lost all his popularity in the Vietnamese community.[36] The protesters had also raised funds for a community center which was built the following year, although there were accusations that the money had been "misspent" on travel by the organizers.[21] Westminster and neighboring Garden Grove would declare themselves "communist-free zones" in 2004, prohibiting visits by Vietnamese officials, partially to avoid similar costly protests.[14]

Trường was convicted on the piracy charges in August 1999, undergoing both jail time and community service.[37] In 2000, he sued the city and police chief of Westminster for four million dollars, claiming they did not adequately protect him from the protesters and thus violated his free speech rights; the lawsuit was rejected the next year.[38] Afterwards, Trường maintained a low profile and did various odd jobs, including underground wiring for Caltrans and collecting recyclables to supplement his welfare payments. He regained some notoriety for the 2004 "press conference" that he attempted to organize against Garden Grove's "communist-free zone" declaration, which ended in heckling and Trường being escorted to his car along with his wife by police.[39] The next year, he sold his property and moved to his birthplace in Đồng Tháp Province, Vietnam with his wife and two children. Along with a local partner, Trường set up an aquaculture company, but was sued by his partner in 2006, leading to the confiscation of his property by the provincial government.[40]

The protests came back into the public consciousness when a television program on Saigon TV was accused of supporting the communists due to the use of a five-second closeup shot of the display. In addition to existing issues around the display of the symbols, language and generational differences were also cited as a cause for the controversy, as it was an English-language program aimed for younger Vietnamese Americans that was shown on a channel that normally broadcast Vietnamese-language content. Although its creators held a public forum to explain that they had not meant to cause offense, new sit-ins encouraged by community radio and dissatisfaction from attendees led to the network deciding to cancel the rest of the show.[41]

In retrospect, the protests were seen as the "largest anti-communist demonstrations in Little Saigon’s history" and possibly the largest protest ever by Vietnamese-Americans, and came to shape the future of the community.[42] The event served as a catalyst in increasing the civic participation of Vietnamese Americans, with several running for a number of public offices.[1] By early 2007, the Vietnamese community had the largest number of politicians in office out of any Asian American group in Orange County.[43] However, the "generation gap" widened as younger activists focused more on domestic issues rather than the "homeland" and anti-communism.[44] As perceptions of the incident by the community have grown more multifaceted, some Asian American artists and scholars have used the controversy as inspiration for intentionally shocking and angering pieces of art as a form of exposure therapy to assist in healing and managing trauma among Vietnamese refugees.[45]

References

editNotes

edit- ^ The spelling Hi-Tek was more predominant in English-language sources, with HiTek also being used; the storefront featured both spellings.

- ^ Often reordered and anglicized to Truong Van Tran; as is customary for Vietnamese names, he should be referred to by his given name Trường.

- ^ See Tsang 1999 for the original column.

Citations

edit- ^ a b c Berg, Haire & Kopetman 2015.

- ^ Tsang 1999.

- ^ Ha 2002, pp. 36–37; Berg, Haire & Kopetman 2015.

- ^ Datta 2013, pp. 155–156; Thompson 2015.

- ^ Meyer & Ông 2008, p. 92; Datta 2013, pp. 156.

- ^ Collet & Lien 2009, pp. 67–68.

- ^ Ha 2002, p. 40.

- ^ Ha 2002, pp. 40–41; Ressner 1999.

- ^ Ha 2002, p. 41-42.

- ^ Meyer & Ông 2008, p. 92.

- ^ Berg, Haire & Kopetman 2015; Ha 2002, pp. 39–40; Mydans 1994.

- ^ Ha 2002; Tran 1999a.

- ^ Tampa Bay Times 1999.

- ^ a b Allen-Kim 2015, pp. 158–159.

- ^ Balassone 2005; Tran & Warren 1999.

- ^ Ha 2002, p. 42.

- ^ a b c Sheppard & Willon 1999.

- ^ a b Ha 2002, p. 43.

- ^ Sheppard & Tran 1999; Sheppard & Willon 1999.

- ^ Terry 1999; Tran 1999d.

- ^ a b Ebnet 2000.

- ^ a b Sanchez 1999.

- ^ Datta 2013, p. 163.

- ^ Tran 1999b.

- ^ Ha 2002, pp. 43, 50–51; Datta 2013, p. 64.

- ^ Ha 2002, pp. 44–45.

- ^ Nguyen & Kurashige 2017.

- ^ Meyer & Ông 2008, p. 97.

- ^ Parsons 1999.

- ^ Sheppard & Tran 1999a.

- ^ Sheppard & Willon 1999; Tran 1999d.

- ^ Sheppard & Willon 1999; Tran 1999c.

- ^ Ha 2002, pp. 47–48.

- ^ Ha 2002, p. 47.

- ^ Tran 1999a.

- ^ Sanchez 1999; Berg, Haire & Kopetman 2015; Wisckol 2016.

- ^ Allen-Kim 2015, p. 159.

- ^ Haldane 2001.

- ^ Tran 2004.

- ^ BBC 2006.

- ^ Võ 2009, pp. 96–97; Datta 2013, pp. 164–165.

- ^ Ha 2002, pp. 40, 51; Datta 2013, p. 162; Okihiro 2014, p. 395.

- ^ Võ 2009, p. 94.

- ^ Meyer & Ông 2008, pp. 97; Le 2011, p. 16.

- ^ Nguyen 2022.

Sources

editBooks

edit- Allen-Kim, Erica (2015). "Chapter Nine - Saigon in the Suburbs: Protest, Exclusion and Visibility". In de Baca, Miguel; Best, Makeda (eds.). Conflict, Identity, and Protest in American Art. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 155–171. ISBN 978-1-4438-8836-3.

- Collet, Christian; Lien, Pei-Te (2009). The Transnational Politics of Asian Americans. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. ISBN 9781592138623. Archived from the original on February 4, 2021. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- Nguyen, Phuong (2017). "Fighting the Postwar in Little Saigon". In Kurashige, Lon (ed.). Pacific America: Histories of Transoceanic Crossings. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 118–120. ISBN 9780824855796. Archived from the original on January 9, 2021. Retrieved January 31, 2021.

- Nguyen, Phuong Tran (2017). Becoming Refugee American: The Politics of Rescue in Little Saigon. University of Illinois Press. pp. 131–135. ISBN 9780252099953. Archived from the original on January 9, 2021. Retrieved January 9, 2021.

- Okihiro, Gary Y., ed. (2014). The Great American Mosaic: An Exploration of Diversity in Primary Documents. Vol. 3: Asian American and Pacific Islander Experience. Santa Barbara, California: Greenwood. ISBN 978-1-61069-612-8. OCLC 870896719.

- Võ, Linda Trinh (April 29, 2009). "Transforming an Ethnic Community". In Ling, Huping (ed.). Asian America: Forming New Communities, Expanding Boundaries (eBook ed.). New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-4867-8. OCLC 647880050.

News articles

edit- Balassone, Merrill (October 23, 2005). "The heart of Little Saigon beats strong". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved February 3, 2021.

- Berg, Tom; Haire, Chris; Kopetman, Roxana (May 1, 2015). "How they became us: Orange County changed forever in the 40 years since the fall of Saigon". Orange County Register. Archived from the original on January 9, 2021. Retrieved January 31, 2021.

- Ebnet, Matthew (January 16, 2000). "Special Report: A year after a Little Saigon merchant touched off protests by displaying a Vietnamese flag . . . A Divided Community Returns to Daily Life". Los Angeles Times. Westminster. Archived from the original on January 9, 2021. Retrieved February 20, 2021.

- Haldane, David (May 25, 2001). "Judge Backs Westminster in Video Store Suit". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 9, 2021. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- Mydans, Seth (September 12, 1994). "California Vietnamese Off to Hanoi". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 26, 2015. Retrieved February 2, 2021.

- Parsons, Dana (March 5, 1999). "Westminster: Noting Irony Isn't Enough". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 9, 2021. Retrieved January 31, 2021.

- Ressner, Jeffrey (March 8, 1999). "The Man Who Brought Back Ho Chi Minh". Time. Retrieved February 1, 2021.

- Sanchez, Rene (March 5, 1999). "Days of Rage in Little Saigon". The Washington Post. Retrieved February 22, 2021.

- Sheppard, Harrison; Tran, Tini (January 22, 1999). "Ho Chi Minh Picture Must Go, Judge Says". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 9, 2021. Retrieved January 31, 2021.

- Sheppard, Harrison; Tran, Tini (March 3, 1999). "Westminster Protest's Scope and Support Spread". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 25, 2021.

- Sheppard, Harrison; Willon, Phil (March 14, 1999). "Past and Present". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 9, 2021. Retrieved January 31, 2021.

- Terry, Don (February 21, 1999). "Display of Ho Chi Minh Poster Spurs Protest and Arrests". The New York Times. p. 32. Archived from the original on January 9, 2021. Retrieved February 20, 2021.

- Thompson, A.C. (November 3, 2015). "Terror in Little Saigon". ProPublica. Archived from the original on January 9, 2021. Retrieved February 1, 2021.

- Tran, Mai (May 19, 2004). "A Reviled Figure Resurfaces to Oppose Unwelcome Mat for Vietnam Officials". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 9, 2021. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- Tran, Tini (February 20, 1999). "In Flag Dispute, Both Sides Vow to Stand Firm". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 9, 2021. Retrieved February 5, 2021.

- Tran, Tini (March 4, 1999). "U.S. Vietnamese Unite Behind County Protesters". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 9, 2021. Retrieved May 17, 2021.

- Tran, Tini (May 28, 1999). "Slurs Aired Amid Tran Protest Not First Time". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 9, 2021. Retrieved February 27, 2021.

- Tran, Tini (August 11, 1999). "Target of Little Saigon Protests Gets 90-Day Term". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 9, 2021. Retrieved February 20, 2021.

- Tran, Tini; Warren, Peter M. (January 19, 1999). "Store's Display of Communist Items Protested". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 9, 2021. Retrieved February 3, 2021.

- Tsang, Daniel C. (January 31, 1999). "Little Saigon Slowly Kicking the Redbaiting Habit". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 9, 2021. Retrieved January 31, 2021.

- Wisckol, Martin (June 10, 2016). "Vietnamese Americans now O.C. political force". Orange County Register. Archived from the original on January 9, 2021. Retrieved March 15, 2021.

- "Judge shields Ho Chi Minh poster in Little Saigon". Tampa Bay Times. February 11, 1999. Retrieved March 16, 2021.

- "Trần Văn Trường: 'Vẫn tin ở quê nhà'" [Trần Văn Trường: 'Still believe in the homeland']. BBC World Service (in Vietnamese). April 10, 2006. Archived from the original on January 9, 2021. Retrieved February 27, 2021.

Research

edit- Datta, Saheli (2013). Determinants of Political Transnationalism Among Vietnamese Americans in the United States (PhD). Syracuse University. Retrieved January 31, 2021.

- Ha, Nam Q. (2002). "4. Anti-Communism and the Hi-Tek incident". Business and politics in Little Saigon, California (Dissertation). Rice University. pp. 35–51. Retrieved January 31, 2021.

- Le, Long S. (2011). "Exploring the Function of the Anti-communist Ideology and Identity in the Vietnamese American Diasporic Community". Journal of Southeast Asian American Education and Advancement. 6 (1). National Association for the Education and Advancement of Cambodian, Laotian, and Vietnamese Americans and Purdue University. doi:10.7771/2153-8999.1030. ISSN 2153-8999.

- Meyer, David S.; Ông, Như-Ngọc T. (February 1, 2008). "Protest and Political Incorporation: Vietnamese American Protests in Orange County, California, 1975–2001". Journal of Vietnamese Studies. 3 (1). University of California Press: 78–107. doi:10.1525/vs.2008.3.1.78. ISSN 1559-372X.

- Nguyen, Minh X. (July 22, 2022). "Commodifying Transnationalism for the General Audience". In Sahoo, Ajaya Kumar (ed.). Routledge Handbook of Asian Transnationalism. London: Routledge. pp. 142–154. doi:10.4324/9781003152149-13. ISBN 978-1-003-15214-9.

- Nguyen, Phuong Tran (2009). The people of the fall: refugee nationalism in Little Saigon, 1975--2005 (PhD). University of Southern California. pp. 256–262. Retrieved January 31, 2021.

External links

edit- Photographs of the Hi-Tek Demonstrations by Lý Kiến Trúc

- USA: VIETNAMESE DEMONSTRATIONS OVER COMMUNIST SYMPATHISER (video by Associated Press)

- AP - USA: VIDEO STORE ORDERED TO REMOVE PORTRAIT OF HO CHI MINH

- 1999...Trần Trường (video of the protests and news coverage)