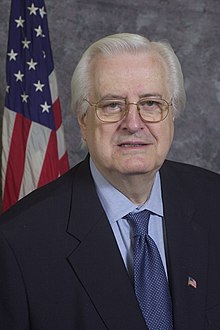

Henry John Hyde (April 18, 1924 – November 29, 2007) was an American politician who served as a Republican member of the United States House of Representatives from 1975 to 2007, representing the 6th District of Illinois, an area of Chicago's northwestern suburbs. He was Chairman of the Judiciary Committee from 1995 to 2001, and the House International Relations Committee from 2001 to 2007. He is most famous for writing the Hyde Amendment, as a vocal opponent of abortion.

Henry Hyde | |

|---|---|

| |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Illinois's 6th district | |

| In office January 3, 1975 – January 3, 2007 | |

| Preceded by | Harold R. Collier |

| Succeeded by | Peter Roskam |

| Chair of the House Foreign Affairs Committee | |

| In office January 3, 2001 – January 3, 2007 | |

| Preceded by | Benjamin Gilman |

| Succeeded by | Tom Lantos |

| Chair of the House Judiciary Committee | |

| In office January 3, 1995 – January 3, 2001 | |

| Preceded by | Jack Brooks |

| Succeeded by | Jim Sensenbrenner |

| Chair of the House Republican Policy Committee | |

| In office January 3, 1993 – January 3, 1995 | |

| Leader | Bob Michel |

| Preceded by | Mickey Edwards |

| Succeeded by | Chris Cox |

| Majority Leader of the Illinois House of Representatives | |

| In office January 13, 1971 – January 10, 1973 | |

| Preceded by | Lewis V. Morgan |

| Succeeded by | William D. Walsh |

| Member of the Illinois House of Representatives from the 18th district | |

| In office January 10, 1973 – January 3, 1975 Serving with Lawrence DiPrima, Robert F. McPartlin | |

| Preceded by | Bernard McDevitt |

| Succeeded by | Robert K. Downs |

| Member of the Illinois House of Representatives from the 16th district | |

| In office January 11, 1967 – January 10, 1973 Serving with Hellmut W. Stolle, William M. Zachacki, Ralph C. Capparelli, Roman J. Kosinski | |

| Preceded by | At-large district abolished |

| Succeeded by | Roger McAuliffe |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Henry John Hyde April 18, 1924 Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Died | November 29, 2007 (aged 83) Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic (before 1952) Republican (1952–2007) |

| Spouse(s) |

Jeanne Simpson

(m. 1947; died 1992)Judy Wolverton |

| Children | 4 |

| Education | Duke University Georgetown University (BA) Loyola University Chicago (JD) |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1944–1968 |

| Rank | |

| Unit | United States Navy Reserve |

Early life and education

editHyde was born in Chicago, the son of Monica (Kelly) and Henry Clay Hyde.[1] His father was English and his mother was Irish Catholic. His family supported the Democratic Party. Hyde graduated from St. George High School in 1942.[2] He attended Duke University, where he joined the Sigma Chi Fraternity, graduated from Georgetown University and obtained his J.D. degree from Loyola University Chicago School of Law. Hyde played basketball for the Georgetown Hoyas where he helped take the team to the 1943 championship game.[3] He served in the Navy during World War II. He remained in the Naval Reserve from 1946 to 1968, as an officer in charge of the U.S. Naval Intelligence Reserve Unit in Chicago. He retired at the rank of Commander. In 1955, Hyde joined the Knights of Columbus, and was a member of Father McDonald Council 1911 in Elmhurst, Illinois.[4]

He was married to Jeanne Simpson Hyde from 1947 until her death in 1992; he had four children and four grandchildren.[5]

Political career

editHyde's political views began drifting rightward after his collegiate years. By 1952, he had become a Republican and supported Dwight Eisenhower for president.[5] He made his first run for Congress in 1962, losing to Democratic incumbent Roman Pucinski in the 11th District.

Hyde was elected to the Illinois House of Representatives in 1967 and served as Majority Leader from 1971 to 1972. He served in the Illinois House until 1974, when he was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in November, 1974 as one of the few bright spots in what was a disastrous year for Republicans in the wake of the Watergate scandal. He faced a bruising contest against former Cook County state's attorney Edward Hanrahan, but was elected by 8,000 votes.

Political positions and legislation

editHyde was one of the most vocal and persistent opponents of abortion in American politics and was the chief sponsor of the eponymous Hyde Amendment to the House Appropriations bill that prohibited the use of federal funds to pay for elective abortions through Medicaid. In 1981, however, he and U.S. Senator Jake Garn of Utah, another abortion opponent, broke with the National Pro-Life Political Action Committee, when its executive director, Peter Gemma, issued a "hit list" to target members of both houses of Congress who supported abortion rights. Hyde said such lists are counterproductive because they create irrevocable discord among legislators, any of whom can be subject to a "single issue" attack of this kind. Gemma said he was surprised by the withdrawal of Garn and Hyde from the PAC committee but continued with plans to spend $650,000 for the 1982 elections on behalf of anti-abortion candidates.[6] In 1993 the 1976 Hyde Amendment law was amended to allow payments for abortions in case of rape, incest, or to save the life of the mother.[7]

An original sponsor of the Brady Bill requiring background checks for gun buyers, Hyde broke with his party in 1994 when he supported a ban on the sale of semi-automatic firearms. An original sponsor of family leave legislation, Hyde said the law promoted "capitalism with a human face." Hyde played a key role in the reauthorization of the Voting Rights Act in 1981.[8]

He was also involved in debates over U.S.-Soviet relations, Central America policy, the War Powers Act, NATO expansion and the investigation of the Iran-Contra affair, and sponsored the United Nations Reform Act of 2005,[9] a bill that ties payment of U.S. dues for United Nations operations to reform of the institution's management.

House committees

editHyde was a member of the House Judiciary Committee for his entire tenure in the House. He was its chairman from 1995 until 2001, during which time he served as the lead manager during the President Clinton impeachment trial.

From 1985 until 1991, Hyde was the ranking Republican on the House Select Committee on Intelligence.[10] Hyde and the committee's senior Democrat, U.S. Rep. Tom Lantos (D-CA), authored America's worldwide response to the HIV/AIDS crisis in 2003 and landmark foreign assistance legislation creating the Millennium Challenge Corporation and expanding U.S. funding for successful microenterprise initiatives.

Savings and Loan scandal

editIn 1981, after leaving the House Banking Committee, Hyde went on the board of directors of Clyde Federal Savings and Loan, whose chairman was one of Hyde's political contributors. According to Salon.com, from 1982 until he left the board in 1984, Hyde used his position on the board of directors to promote the savings and loan's investment in risky financial options. In 1990, the federal government put Clyde in receivership, and paid $67 million to cover insured deposits. In 1993, the Resolution Trust Corporation sued Hyde and other directors for $17.2 million. Four years later, before pretrial investigation and depositions, the government settled with the defendants for $850,000 and made an arrangement exempting Hyde from paying anything. According to Salon.com, Hyde was the only member of the congress sued for "gross negligence" in an S&L failure.[11]

Iran–Contra investigation

editAs a member of the congressional panel investigating the Iran-Contra affair, Hyde vigorously defended the Ronald Reagan administration, and a number of the participants who had been accused of various crimes, particularly Oliver North.[12] Quoting Thomas Jefferson, Hyde argued that although various individuals had lied in testimony before Congress, their actions were excusable because they were in support of the goal of fighting communism.[13]

Clinton impeachment

editHyde argued that the House had a constitutional and civic duty to impeach Bill Clinton for perjury. In the Resolution on Impeachment of the President, Hyde wrote:[14]

What we are telling you today are not the ravings of some vast right-wing conspiracy, but a reaffirmation of a set of values that are tarnished and dim these days, but it is given to us to restore them so our Founding Fathers would be proud. It's your country—the President is our flag bearer, out in front of our people. The flag is falling, my friends—I ask you to catch the falling flag as we keep our appointment with history.

Clinton was impeached by the House on two charges: perjury and obstruction of justice. Hyde served as chief House manager (prosecutor) at the President's trial in the Senate; he became known for his remarks in his closing argument:

A failure to convict will make the statement that lying under oath, while unpleasant and to be avoided, is not all that serious ... We have reduced lying under oath to a breach of etiquette, but only if you are the President ... And now let us all take our place in history on the side of honor, and, oh, yes, let right be done.

Despite Hyde's efforts, President Clinton was acquitted of both perjury and obstruction of justice. With a two-thirds majority required for conviction, only 45 senators voted for conviction on the perjury charge and only 50 on the obstruction of justice charge.[15]

Despite being on opposites sides during the impeachment, Hyde was good friends with representative Barney Frank who praised his efforts to keep the impeachment "personality free".[16]

Extramarital affair

editWhile Hyde was spearheading the impeachment of President Bill Clinton amid the revelations of the Clinton–Lewinsky affair, it was revealed that Hyde himself had conducted an extramarital sexual affair with a former beauty stylist named Cherie Snodgrass, who was also married. Hyde admitted to the affair and attributed the relationship as a "youthful indiscretion". He was 41 years old and married when the affair occurred. Hyde said the affair ended when Snodgrass' husband confronted Mrs. Hyde. At the time, Snodgrass was 29, also married and had three children.[17]

The Snodgrasses divorced in 1967. The Hydes reconciled and remained married until Mrs. Hyde's death in 1992.[18]

9/11 and the Iraq War

editAs Chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee, Hyde was involved in some of the highest level debates concerning the response to the September 11 attacks in 2001. In the aftermath of the September 11, 2001 attacks, Hyde cautioned against attacking Iraq in the absence of clear evidence of Iraqi complicity, telling CNN's Robert Novak that it "would be a big mistake."[19] One year later, however, he voted in support of the October 10, 2002 House resolution that authorized the president to go to war with Iraq. In response to Rep. Ron Paul's resolution requesting a formal declaration of war, Hyde stated: "There are things in the Constitution that have been overtaken by events, by time. Declaration of war is one of them. ... Inappropriate, anachronistic, it isn't done anymore."[20]

In 2006, Hyde made the following observation in regard to the Bush Administration's proclaimed objective of promoting democracy in the Middle East:

Lashing our interests to the indiscriminate promotion of democracy is a tempting but unwarranted strategy, more a leap of faith than a sober calculation. There are other negative consequences as well. A broad and energetic promotion of democracy in other countries that will not enjoy our long-term and guiding presence may equate not to peace and stability but to revolution.[21]

Retirement

editHyde was reelected 15 times with no substantive opposition. This was mainly because, over time, his district was pushed further into DuPage County, a longstanding bastion of suburban Republicanism. However, by the turn of the century, the demographics of his district shifted, leading his 2004 Democratic challenger Christine Cegelis to garner over 44% of the vote—Hyde's closest race since his initial run for the seat. On April 18, 2005 (his 81st birthday), Hyde announced on his website that he would retire at the expiration of his term (in January 2007).[22] A few days earlier, it had been reported that Illinois Republicans were expecting this announcement, and it was further reported that Illinois State Senator Peter Roskam had emerged as a leading contender for the Republican Party's nomination. In August 2005, Hyde endorsed Roskam as his successor.[23]

Order of St. Gregory

editHyde was named a Papal Knight of the Order of St. Gregory the Great by Pope Benedict XVI in 2006, in recognition of his longtime support for political issues important to the Roman Catholic Church.

Presidential Medal of Freedom

editHyde received the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation's highest civilian honor, on November 5, 2007, awarded by President Bush.[24] Hyde was hospitalized, recovering from open-heart surgery, and could not attend the ceremony in person.

Death

editHyde died November 29, 2007, nearly eleven months after leaving office, at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago following complications from open heart surgery at Provena Mercy Medical Center in Aurora, Illinois several months earlier. His funeral Mass was presided by Cardinal Francis George of Chicago, and was attended by several dignitaries, including then Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi and future Speaker of the House John Boehner, at St. John Neumann Catholic Church in Saint Charles, Illinois.[25]

See also

edit- Hyde Amendment regarding federal payment for abortions

- Hyde Amendment (1997)

- List of federal political sex scandals in the United States

References

edit- ^ "Hyde, Henry John". American National Biography Online.

- ^ "Henry Hyde, the man behind the anti-abortion amendment Biden now opposes". Chicago Sun-Times. June 7, 2019.

- ^ McDevitt, Caitlin & Sarinsky, Max (December 4, 2007). "Georgetown Mourns Death of Henry Hyde". The Hoya.

- ^ ""Few In Public Life Have Served As Well," Supreme Knight Says". Knights of Columbus. November 29, 2007. Archived from the original on November 16, 2018. Retrieved January 23, 2017.

- ^ a b "Official biography". U.S. House of Representatives. Archived from the original on February 7, 2003. Retrieved February 1, 2013. at Hyde's congressional site

- ^ "The Nation: Congressmen; Draw the Line at; New 'Hit List'". The New York Times. June 7, 1981. Retrieved May 23, 2016.

- ^ "Unknown". EBSCO Industries. Retrieved February 2, 2019.

- ^ "Henry J. Hyde, a Power in the House of Representatives, Dies at 83". November 30, 2007.

- ^ H.R. 2745

- ^ "Biography". Archived from the original on July 5, 2002.

- ^ Moberg, David (June 7, 1999). "The real Henry Hyde scandal". Salon. Archived from the original on December 2, 2007.

- ^ Butterfield, Fox (May 26, 1987). "Republicans on Iran-Contra panel at odds over best tactics to use". The New York Times.

- ^ Savage, David G. (December 4, 1998). "Hyde View on Lying Is Back Haunting Him". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Hyde, Henry (December 18, 1998). "Statement of The Honorable Henry J. Hyde". House Judiciary Committee. Archived from the original on May 17, 2011.

- ^ Senate LIS (February 12, 1999). "U.S. Senate Roll Call Votes 106th Congress – 1st Session: vote number 18 – Guilty or Not Guilty (Art II, Articles of Impeachment v. President W. J. Clinton)". United States Senate. Archived from the original on January 2, 2003. Retrieved April 20, 2010.

- ^ Sally Quinn. "Rep. Barney Frank, Minority Wit". The Washington Post.

- ^ Kurtz, Howard (September 17, 1998). "Report of Hyde Affair Stirs Anger". The Washington Post. p. A15.

- ^ Talbot, David (September 18, 1998). "This hypocrite broke up my family". Salon. Archived from the original on May 11, 2000. Retrieved December 9, 2014.

- ^ Jeffrey, Terence P. (October 29, 2001). "Do we need a war with Iraq?". Human Events.

- ^ Yates, Steven (April 7, 2004). "An Evening With Dr. Ron Paul". Lew Rockwell. Archived from the original on March 13, 2014. Retrieved June 13, 2007.

- ^ Hyde, Henry. "Perils of the Golden Theory", speech in Congress on February 26, 2006.

- ^ "Rep. Henry Hyde announces retirement". NBC News. April 19, 2005.

- ^ "Hyde endorses Roskam". Chicago Tribune. August 5, 2005.

- ^ "Citations Recipients of the Presidential Medal of Freedom". The White House. November 5, 2007. Retrieved March 11, 2013.

- ^ "Video: Henry Hyde laid to rest". The Daily Register. December 8, 2007.

External links

edit- Biography at the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress

- USC Center on Public Diplomacy Profile

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Letter to the FDIC concerning Hyde and the failed Clyde Federal Savings and Loan Archived June 17, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- Memorial Addresses and Other Tributes Held in the House of Representatives and Senate of the United States Together with a Memorial Service in Honor of Henry J. Hyde, Late a Representative from Illinois: One Hundred Tenth Congress, First Session