High mobility group box 1 protein, also known as high-mobility group protein 1 (HMG-1) and amphoterin, is a protein that in humans is encoded by the HMGB1 gene.[3][4]

HMG-1 belongs to the high mobility group and contains a HMG-box domain.

Function

editLike the histones, HMGB1 is among the most important chromatin proteins. In the nucleus HMGB1 interacts with nucleosomes, transcription factors, and histones.[5] This nuclear protein organizes the DNA and regulates transcription.[6] After binding, HMGB1 bends[7] DNA, which facilitates the binding of other proteins. HMGB1 supports transcription of many genes in interactions with many transcription factors. It also interacts with nucleosomes to loosen packed DNA and remodel the chromatin. Contact with core histones changes the structure of nucleosomes.

The presence of HMGB1 in the nucleus depends on posttranslational modifications. When the protein is not acetylated, it stays in the nucleus, but hyperacetylation on lysine residues causes it to translocate into the cytosol.[6]

HMGB1 has been shown to play an important role in helping the RAG endonuclease form a paired complex during V(D)J recombination.[8]

Role in inflammation

editHMGB1 is secreted by immune cells (e.g. macrophages, monocytes and dendritic cells) through leaderless secretory pathway.[6] Activated macrophages and monocytes secrete HMGB1 as a cytokine mediator of inflammation.[9] Antibodies that neutralize HMGB1 confer protection against damage and tissue injury during arthritis, colitis, ischemia, sepsis, endotoxemia, and systemic lupus erythematosus.[citation needed] The mechanism of inflammation and damage consists of binding to toll-like receptor TLR2 and TLR4, which mediates HMGB1-dependent activation of macrophage cytokine release. This positions HMGB1 at the intersection of sterile and infectious inflammatory responses.[10][11]

ADP-ribosylation of HMGB1 by PARP1 inhibits removal of apoptotic cells, thereby sustaining inflammation.[12] TLR4 binding by HMGB1 or lipopolysaccharide (LPS) sustains ADP-ribosylation of HMGB1 by PARP1 thereby serving as an amplification loop for inflammation.[12]

HMGB1 has been proposed as a DNA vaccine adjuvant.[13] HMGB1 released from tumour cells was demonstrated to mediate anti-tumour immune responses by activating toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) signaling on bone marrow-derived GBM-infiltrating DCs.[14]

Interactions

editHMGB1 has to interact with p53.[15][16]

HMGB1 is a nuclear protein that binds to DNA and acts as an architectural chromatin-binding factor. It can also be released from cells, an extracellular form in which it may bind to toll-like receptors (TLRs) or an inflammatory receptor called the receptor for advanced glycation end-products RAGE. Release from cells seems to involve two distinct processes: necrosis, in which case cell membranes are permeabilized and intracellular constituents may diffuse out of the cell; and some form of active or facilitated secretion induced by signaling through the NF-κB. HMGB1 also translocates to the cytosol under stressful conditions such as increased ROS inside the cells. Under such conditions, HMGB1 promotes cell survival by sustaining autophagy through interactions with beclin-1. It is largely considered as an antiapoptotic protein.

HMGB1 can interact with TLR ligands and cytokines, and activates cells through the multiple surface receptors including TLR2, TLR4, and RAGE.[17]

Interaction via TLR4

editSome actions of HMGB1 are mediated through the toll-like receptors (TLRs).[18] Interaction between HMGB1 and TLR4 results in upregulation of NF-κB, which leads to increased production and release of cytokines. HMGB1 is also able to interact with TLR4 on neutrophils to stimulate the production of reactive oxygen species by NADPH oxidase.[6][19] HMGB1-LPS complex activates TLR4, and causes the binding of adapter proteins (MyD88 and others), leading to signal transduction and the activation of various signaling cascades. The downstream effect of this signaling is to activate MAPK and NF-κB, and thus cause the production of inflammatory molecules such as cytokines.[20][21]

Clinical significance

editHMGB1 has been proposed as a target for cancer therapy,[22] as well as a vector for reducing inflammation from SARS-CoV-2 infection. [23] It also serves as a biomarker for post-COVID-19 condition.[24]

The neurodegenerative disease spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 (SCA1) is caused by mutation in the ataxin 1 gene. In a mouse model of SCA1, mutant ataxin 1 protein mediated the reduction or inhibition of HMGB1 in the mitochondria of neurons.[25] HMGB1 regulates DNA architectural changes essential for repair of DNA damage. In the SCA1 mouse model, over-expression of the HMGB1 protein by means of an introduced virus vector bearing the HMGB1 gene facilitated repair of the mitochondrial DNA damage, ameliorated the neuropathology and the motor defects of the SCA1 mice, and also extended their lifespan.[25] Thus impairment of HMGB1 function appears to have a key role in the pathogenesis of SCA1.

Recently, a study provided evidence of an association between raised levels of HMGB1 and attention to detail and systemizing in unmedicated children with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder (ASD), suggesting that inflammatory processes mediated by HMGB1 may play a role in the disruption of neurobiological mechanisms regulating cognitive processes in ASD.[26] In this study, HMGB1 serum concentrations in children with ASD were found significantly higher than those of typically developing children. Additionally, HMGB1 serum concentrations were positively correlated with the Autistic quotient (AQ) attention to detail score and the Systemizing Quotient (SQ) total score in the ASD group.[27] However, comprehensive evidence in children is limited, highlighting the need for in-depth research towards understanding possible mechanisms linking HMGB1 with the core features of ASD. Nevertheless, it has been suggested that HMGB1 could be a reliable inflammatory marker, explaining the link between inflammatory processes and several autistic traits, and therefore a possible therapeutic target in this neurodevelopmental disorder.

References

edit- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000189403 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

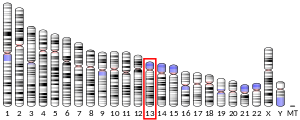

- ^ Ferrari S, Finelli P, Rocchi M, Bianchi ME (July 1996). "The active gene that encodes human high mobility group 1 protein (HMG1) contains introns and maps to chromosome 13". Genomics. 35 (2): 367–71. doi:10.1006/geno.1996.0369. PMID 8661151.

- ^ Chou DK, Evans JE, Jungalwala FB (April 2001). "Identity of nuclear high-mobility-group protein, HMG-1, and sulfoglucuronyl carbohydrate-binding protein, SBP-1, in brain". Journal of Neurochemistry. 77 (1): 120–31. doi:10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.t01-1-00209.x (inactive 23 December 2024). PMID 11279268.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of December 2024 (link) - ^ Bianchi ME, Agresti A (October 2005). "HMG proteins: dynamic players in gene regulation and differentiation". Current Opinion in Genetics & Development. 15 (5): 496–506. doi:10.1016/j.gde.2005.08.007. PMID 16102963.

- ^ a b c d Klune JR, Dhupar R, Cardinal J, Billiar TR, Tsung A (2008). "HMGB1: endogenous danger signaling". Molecular Medicine. 14 (7–8): 476–84. doi:10.2119/2008-00034.Klune. PMC 2323334. PMID 18431461.

- ^ Murugesapillai D, McCauley MJ, Maher LJ, Williams MC (February 2017). "Single-molecule studies of high-mobility group B architectural DNA bending proteins". Biophysical Reviews. 9 (1): 17–40. doi:10.1007/s12551-016-0236-4. PMC 5331113. PMID 28303166.

- ^ Ciubotaru M, Trexler AJ, Spiridon LN, Surleac MD, Rhoades E, Petrescu AJ, Schatz DG (February 2013). "RAG and HMGB1 create a large bend in the 23RSS in the V(D)J recombination synaptic complexes". Nucleic Acids Research. 41 (4): 2437–54. doi:10.1093/nar/gks1294. PMC 3575807. PMID 23293004.

- ^ Wang H, Bloom O, Zhang M, Vishnubhakat JM, Ombrellino M, Che J, Frazier A, Yang H, Ivanova S, Borovikova L, Manogue KR, Faist E, Abraham E, Andersson J, Andersson U, Molina PE, Abumrad NN, Sama A, Tracey KJ (July 1999). "HMG-1 as a late mediator of endotoxin lethality in mice". Science. 285 (5425): 248–51. doi:10.1126/science.285.5425.248. PMID 10398600.

- ^ Yang H, Hreggvidsdottir HS, Palmblad K, Wang H, Ochani M, Li J, Lu B, Chavan S, Rosas-Ballina M, Al-Abed Y, Akira S, Bierhaus A, Erlandsson-Harris H, Andersson U, Tracey KJ (June 2010). "A critical cysteine is required for HMGB1 binding to Toll-like receptor 4 and activation of macrophage cytokine release". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 107 (26): 11942–7. Bibcode:2010PNAS..10711942Y. doi:10.1073/pnas.1003893107. PMC 2900689. PMID 20547845.

- ^ Yang H, Tracey KJ (2010). "Targeting HMGB1 in inflammation". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Gene Regulatory Mechanisms. 1799 (1–2): 149–56. doi:10.1016/j.bbagrm.2009.11.019. PMC 4533842. PMID 19948257.

- ^ a b Pazzaglia S, Pioli C (2019). "Multifaceted Role of PARP-1 in DNA Repair and Inflammation: Pathological and Therapeutic Implications in Cancer and Non-Cancer Diseases". Cells. 9 (1): 41. doi:10.3390/cells9010041. PMC 7017201. PMID 31877876.

- ^ Fagone P, Shedlock DJ, Bao H, Kawalekar OU, Yan J, Gupta D, Morrow MP, Patel A, Kobinger GP, Muthumani K, Weiner DB (November 2011). "Molecular adjuvant HMGB1 enhances anti-influenza immunity during DNA vaccination". Gene Therapy. 18 (11): 1070–7. doi:10.1038/gt.2011.59. PMC 4141626. PMID 21544096.

- ^ Curtin JF, Liu N, Candolfi M, Xiong W, Assi H, Yagiz K, Edwards MR, Michelsen KS, Kroeger KM, Liu C, Muhammad AK, Clark MC, Arditi M, Comin-Anduix B, Ribas A, Lowenstein PR, Castro MG (January 2009). "HMGB1 mediates endogenous TLR2 activation and brain tumor regression". PLOS Medicine. 6 (1): e10. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000010. PMC 2621261. PMID 19143470.

- ^ Imamura T, Izumi H, Nagatani G, Ise T, Nomoto M, Iwamoto Y, Kohno K (March 2001). "Interaction with p53 enhances binding of cisplatin-modified DNA by high mobility group 1 protein". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 276 (10): 7534–40. doi:10.1074/jbc.M008143200. PMID 11106654.

- ^ Dintilhac A, Bernués J (March 2002). "HMGB1 interacts with many apparently unrelated proteins by recognizing short amino acid sequences". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (9): 7021–8. doi:10.1074/jbc.M108417200. hdl:10261/112516. PMID 11748221.

- ^ Sims GP, Rowe DC, Rietdijk ST, Herbst R, Coyle AJ (2010). "HMGB1 and RAGE in inflammation and cancer". Annual Review of Immunology. 28: 367–88. doi:10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132603. PMID 20192808.

- ^ Ibrahim ZA, Armour CL, Phipps S, Sukkar MB (December 2013). "RAGE and TLRs: relatives, friends or neighbours?". Molecular Immunology. 56 (4): 739–44. doi:10.1016/j.molimm.2013.07.008. PMID 23954397.

- ^ Park JS, Gamboni-Robertson F, He Q, Svetkauskaite D, Kim JY, Strassheim D, Sohn JW, Yamada S, Maruyama I, Banerjee A, Ishizaka A, Abraham E (March 2006). "High mobility group box 1 protein interacts with multiple Toll-like receptors". American Journal of Physiology. Cell Physiology. 290 (3): C917-24. doi:10.1152/ajpcell.00401.2005. PMID 16267105. S2CID 21350171.

- ^ Bianchi ME (September 2009). "HMGB1 loves company". Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 86 (3): 573–6. doi:10.1189/jlb.1008585. PMID 19414536.

- ^ Hreggvidsdóttir HS, Lundberg AM, Aveberger AC, Klevenvall L, Andersson U, Harris HE (March 2012). "High mobility group box protein 1 (HMGB1)-partner molecule complexes enhance cytokine production by signaling through the partner molecule receptor". Molecular Medicine. 18 (2): 224–30. doi:10.2119/molmed.2011.00327. PMC 3320135. PMID 22076468.

- ^ Lotze MT, DeMarco RA (December 2003). "Dealing with death: HMGB1 as a novel target for cancer therapy". Current Opinion in Investigational Drugs. 4 (12): 1405–1409. PMID 14763124.

- ^ Andersson U, Ottestad W, Tracey KJ (May 2020). "Extracellular HMGB1: a therapeutic target in severe pulmonary inflammation including COVID-19?". Molecular Medicine. 26 (1): 42. doi:10.1186/s10020-020-00172-4. PMC 7203545. PMID 32380958.

- ^ Ryan FJ, Hope CM, Masavuli MG, Lynn MA, Mekonnen ZA, Yeow AE, et al. (January 2022). "Long-term perturbation of the peripheral immune system months after SARS-CoV-2 infection". BMC Medicine. 20 (1): 26. doi:10.1186/s12916-021-02228-6. PMC 8758383. PMID 35027067.

- ^ a b Ito H, Fujita K, Tagawa K, Chen X, Homma H, Sasabe T, Shimizu J, Shimizu S, Tamura T, Muramatsu S, Okazawa H (January 2015). "HMGB1 facilitates repair of mitochondrial DNA damage and extends the lifespan of mutant ataxin-1 knock-in mice". EMBO Molecular Medicine. 7 (1): 78–101. doi:10.15252/emmm.201404392. PMC 4309669. PMID 25510912.

- ^ Makris G, Chouliaras G, Apostolakou F, Papageorgiou C, Chrousos G, Papassotiriou I, Pervanidou P (2021). "Increased serum concentrations of high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) protein in children with Autism Spectrum Disorder". Children. 8 (6): 478. doi:10.3390/children8060478. PMC 8228126. PMID 34198762.

- ^ Makris G, Chouliaras G, Apostolakou F, Papageorgiou C, Chrousos G, Papassotiriou I, Pervanidou P (2021). "Increased serum concentrations of high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) protein in children with Autism Spectrum Disorder". Children. 8 (6): 478. doi:10.3390/children8060478. PMC 8228126. PMID 34198762.

Further reading

edit- Thomas JO, Travers AA (March 2001). "HMG1 and 2, and related 'architectural' DNA-binding proteins". Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 26 (3): 167–74. doi:10.1016/S0968-0004(01)01801-1. PMID 11246022.

- Andersson U, Erlandsson-Harris H, Yang H, Tracey KJ (December 2002). "HMGB1 as a DNA-binding cytokine". Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 72 (6): 1084–91. doi:10.1189/jlb.72.6.1084. PMID 12488489. S2CID 11409274.

- Wu H, Wu T, Hua W, Dong X, Gao Y, Zhao X, Chen W, Cao W, Yang Q, Qi J, Zhou J, Wang J (March 2015). "PGE2 receptor agonist misoprostol protects brain against intracerebral hemorrhage in mice". Neurobiology of Aging. 36 (3): 1439–50. doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.12.029. PMC 4417504. PMID 25623334.

- Erlandsson Harris H, Andersson U (June 2004). "Mini-review: The nuclear protein HMGB1 as a proinflammatory mediator". European Journal of Immunology. 34 (6): 1503–12. doi:10.1002/eji.200424916. PMID 15162419. S2CID 11470463.

- Jiang W, Pisetsky DS (January 2007). "Mechanisms of Disease: the role of high-mobility group protein 1 in the pathogenesis of inflammatory arthritis". Nature Clinical Practice. Rheumatology. 3 (1): 52–8. doi:10.1038/ncprheum0379. PMID 17203009. S2CID 428632.

- Ellerman JE, Brown CK, de Vera M, Zeh HJ, Billiar T, Rubartelli A, Lotze MT (May 2007). "Masquerader: high mobility group box-1 and cancer". Clinical Cancer Research. 13 (10): 2836–48. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1953. PMID 17504981. S2CID 32922516.

- Fossati S, Chiarugi A (2007). "Relevance of high-mobility group protein box 1 to neurodegeneration". International Review of Neurobiology. 82: 137–48. doi:10.1016/S0074-7742(07)82007-1. ISBN 9780123739896. PMID 17678959.

- Parkkinen J, Rauvala H (September 1991). "Interactions of plasminogen and tissue plasminogen activator (t-PA) with amphoterin. Enhancement of t-PA-catalyzed plasminogen activation by amphoterin". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 266 (25): 16730–5. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)55362-X. PMID 1909331.

- Wen L, Huang JK, Johnson BH, Reeck GR (February 1989). "A human placental cDNA clone that encodes nonhistone chromosomal protein HMG-1". Nucleic Acids Research. 17 (3): 1197–214. doi:10.1093/nar/17.3.1197. PMC 331735. PMID 2922262.

- Bernués J, Espel E, Querol E (May 1986). "Identification of the core-histone-binding domains of HMG1 and HMG2". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Gene Structure and Expression. 866 (4): 242–51. doi:10.1016/0167-4781(86)90049-7. PMID 3697355.

- Ge H, Roeder RG (June 1994). "The high mobility group protein HMG1 can reversibly inhibit class II gene transcription by interaction with the TATA-binding protein". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 269 (25): 17136–40. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(17)32531-0. PMID 8006019.

- Parkkinen J, Raulo E, Merenmies J, Nolo R, Kajander EO, Baumann M, Rauvala H (September 1993). "Amphoterin, the 30-kDa protein in a family of HMG1-type polypeptides. Enhanced expression in transformed cells, leading edge localization, and interactions with plasminogen activation". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 268 (26): 19726–38. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)36575-5. PMID 8366113.

- Zappavigna V, Falciola L, Helmer-Citterich M, Mavilio F, Bianchi ME (September 1996). "HMG1 interacts with HOX proteins and enhances their DNA binding and transcriptional activation". The EMBO Journal. 15 (18): 4981–91. doi:10.1002/j.1460-2075.1996.tb00878.x. PMC 452236. PMID 8890171.

- Xiang YY, Wang DY, Tanaka M, Suzuki M, Kiyokawa E, Igarashi H, Naito Y, Shen Q, Sugimura H (February 1997). "Expression of high-mobility group-1 mRNA in human gastrointestinal adenocarcinoma and corresponding non-cancerous mucosa". International Journal of Cancer. 74 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19970220)74:1<1::AID-IJC1>3.0.CO;2-6. PMID 9036861.

- Rasmussen RK, Ji H, Eddes JS, Moritz RL, Reid GE, Simpson RJ, Dorow DS (1997). "Two-dimensional electrophoretic analysis of human breast carcinoma proteins: mapping of proteins that bind to the SH3 domain of mixed lineage kinase MLK2". Electrophoresis. 18 (3–4): 588–98. doi:10.1002/elps.1150180342. PMID 9150946. S2CID 37336552.

- Jayaraman L, Moorthy NC, Murthy KG, Manley JL, Bustin M, Prives C (February 1998). "High mobility group protein-1 (HMG-1) is a unique activator of p53". Genes & Development. 12 (4): 462–72. doi:10.1101/gad.12.4.462. PMC 316524. PMID 9472015.

- Milev P, Chiba A, Häring M, Rauvala H, Schachner M, Ranscht B, Margolis RK, Margolis RU (March 1998). "High affinity binding and overlapping localization of neurocan and phosphacan/protein-tyrosine phosphatase-zeta/beta with tenascin-R, amphoterin, and the heparin-binding growth-associated molecule". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 273 (12): 6998–7005. doi:10.1074/jbc.273.12.6998. PMID 9507007.

- Nagaki S, Yamamoto M, Yumoto Y, Shirakawa H, Yoshida M, Teraoka H (May 1998). "Non-histone chromosomal proteins HMG1 and 2 enhance ligation reaction of DNA double-strand breaks". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 246 (1): 137–41. doi:10.1006/bbrc.1998.8589. PMID 9600082.

- Claudio JO, Liew CC, Dempsey AA, Cukerman E, Stewart AK, Na E, Atkins HL, Iscove NN, Hawley RG (May 1998). "Identification of sequence-tagged transcripts differentially expressed within the human hematopoietic hierarchy". Genomics. 50 (1): 44–52. doi:10.1006/geno.1998.5308. PMID 9628821.

- Boonyaratanakornkit V, Melvin V, Prendergast P, Altmann M, Ronfani L, Bianchi ME, Taraseviciene L, Nordeen SK, Allegretto EA, Edwards DP (August 1998). "High-mobility group chromatin proteins 1 and 2 functionally interact with steroid hormone receptors to enhance their DNA binding in vitro and transcriptional activity in mammalian cells". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 18 (8): 4471–87. doi:10.1128/mcb.18.8.4471. PMC 109033. PMID 9671457.

- Wu H, Wu T, Han X, Wan J, Jiang C, Chen W, Lu H, Yang Q, Wang J (January 2017). "Cerebroprotection by the neuronal PGE2 receptor EP2 after intracerebral hemorrhage in middle-aged mice". Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 37 (1): 39–51. doi:10.1177/0271678X15625351. PMC 5363749. PMID 26746866.

- Jiao Y, Wang HC, Fan SJ (December 2007). "Growth suppression and radiosensitivity increase by HMGB1 in breast cancer". Acta Pharmacologica Sinica. 28 (12): 1957–67. doi:10.1111/j.1745-7254.2007.00669.x. PMID 18031610.

- Andersson U, Ottestad W, Tracey KJ (May 2020). "Extracellular HMGB1: a therapeutic target in severe pulmonary inflammation including COVID-19?". Mol Med. 26 (1): 42(2020). doi:10.1186/s10020-020-00172-4. PMC 7203545. PMID 32380958.

External links

edit- HMGB1+protein,+human at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Pancreatic Cancer Research and HMGB1 Signaling Pathway

- PDBe-KB provides an overview of all the structure information available in the PDB for Human High mobility group protein B1 (HMGB1)

- PDBe-KB provides an overview of all the structure information available in the PDB for Rat High mobility group protein B1 (HMGB1)