The grey-tailed tattler (Tringa brevipes, formerly Heteroscelus brevipes[3][4]), also known as the Siberian tattler or Polynesian tattler,[2] is a small shorebird in the genus Tringa. The English name for the tattlers refers to their noisy call.[5] The genus name Tringa is the Neo-Latin name given to the green sandpiper by Aldrovandus in 1599 based on Ancient Greek trungas, a thrush-sized, white-rumped, tail-bobbing wading bird mentioned by Aristotle. The specific brevipes is from Latin brevis, "short", and pes, "foot".[6]

| Grey-tailed tattler | |

|---|---|

| |

| Breeding plumage | |

| |

| Non-breeding plumage | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Charadriiformes |

| Family: | Scolopacidae |

| Genus: | Tringa |

| Species: | T. brevipes

|

| Binomial name | |

| Tringa brevipes (Vieillot, 1816)

| |

| Synonyms[2] | |

|

Heteroscelus brevipes | |

This tattler breeds in northeast Siberia. After breeding, they migrate to an area from southeast Asia to Australia.

Description

editThe grey-tailed tattler is closely related to its North American counterpart, the wandering tattler (T. incana) and is difficult to distinguish from that species. Both tattlers are unique among the species of Tringa for having unpatterned, greyish wings and back, and a scaly breast pattern extending more or less onto the belly in breeding plumage, in which both also have a rather prominent supercilium.

These birds resemble common redshanks in shape and size. The upper parts, underwings, face and neck are grey, and the belly is white. They have short yellowish legs and a bill with a pale base and dark tip. There is a weak supercilium.

They are very similar to their American counterpart, and differentiation depends on details like the length of the nasal groove and scaling on the tarsus. The best distinction is the call; grey-tailed has a disyllabic whistle, and wandering a rippling trill.

Behaviour

editIts breeding habitat is stony riverbeds in northeast Siberia. It nests on the ground, but these birds will perch in trees. They sometimes use old nests of other birds as well.

Grey-tailed tattlers are strongly migratory and winter on muddy and sandy coasts from southeast Asia to Australia. They are very rare vagrants to western North America and western Europe. These are not particularly gregarious birds and are seldom seen in large flocks except at roosts.

These birds forage on the ground or water, picking up food by sight. They eat insects, crustaceans and other invertebrates.

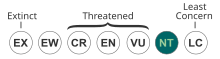

Conservation status

editAustralia

editGrey-tailed tattlers are not listed as "threatened" on the Australian Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999.

The grey-tailed tattler is listed as "threatened" on the Victorian Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act (1988). Under this Act, an Action Statement for the recovery and future management of this species has not been prepared. On the 2007 advisory list of threatened vertebrate fauna in Victoria, the grey-tailed tattler is listed as critically endangered.[7]

References

edit- ^ BirdLife International (2016). "Tringa brevipes". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T22693289A93394897. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22693289A93394897.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ a b "Tringa brevipes". Avibase.

- ^ Banks, Richard C.; Cicero, Carla; Dunn, Jon L.; Kratter, Andrew W.; Rasmussen, Pamela C.; Remsen, J. V. Jr.; Rising, James D. & Stotz, Douglas F. (2006): Forty-seventh Supplement to the American Ornithologists' Union Check-list of North American Birds. Auk 123(3): 926–936. DOI: 10.1642/0004-8038(2006)123[926:FSTTAO]2.0.CO;2

- ^ *Pereira, Sérgio Luiz & Baker, Alan J. (2005): Multiple Gene Evidence for Parallel Evolution and Retention of Ancestral Morphological States in the Shanks (Charadriiformes: Scolopacidae). Condor 107(3): 514–526. DOI: 10.1650/0010-5422(2005)107[0514:MGEFPE]2.0.CO;2

- ^ "Tattler". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Jobling, James A (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 77, 390. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- ^ Victorian Department of Sustainability and Environment (2007). Advisory List of Threatened Vertebrate Fauna in Victoria – 2007. East Melbourne, Victoria: Department of Sustainability and Environment. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-74208-039-0.