The Great Platte River Road was a major overland travel corridor approximately following the course of the Platte River in present-day Nebraska and Wyoming that was shared by several popular emigrant trails during the 19th century, including the Trapper's Trail, the Oregon Trail, the Mormon Trail, the California Trail, the Pony Express route, and the military road connecting Fort Leavenworth and Fort Laramie. The road, which extended nearly 370 miles (600 km) from the Second Fort Kearny to Fort Laramie, was utilized primarily from 1841 to 1866. In modern times it is often regarded as a sort of superhighway of its era, and has been referred to as "the grand corridor of America's westward expansion".[1][2]

Route

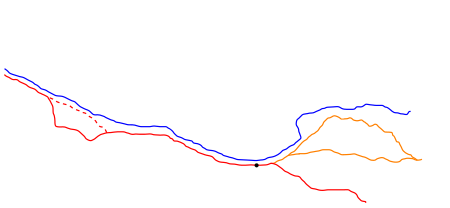

editThe route that would become the Great Platte River Road began in any of several places along the Missouri River, including Omaha, Council Bluffs, Nebraska City, St. Joseph and Kansas City. Each of these separate trails eventually converged near Fort Kearny in the middle of the Nebraska Territory. For those coming from Omaha and Council Bluffs, the trail traversed the north side of the Platte River; those coming from St. Joseph and Kansas City generally used the south side of the river. At some point along the Platte, the travelers would cross to the north side, frequently at great hazard, in order to continue following the road to Fort Laramie.[3] The main stem of the Platte River is formed by the confluence of two smaller branches in western Nebraska; beyond this confluence, some of the emigrant trails continued northwest along the North Platte River, including the Oregon, California, and Mormon Trails, while others turned southwest to follow the South Platte River, including the Overland Trail.

History

editRobert Stuart, an explorer with the Pacific Fur Company, was one of the first European-Americans to explore the potential for the route in the 1810s. As the United States continued to organize new territory in the West, emigration became increasingly popular. Thousands of settlers began to move west along the routes of earlier trail blazers, many of which simply followed the east-west course of the Platte River, which offered an easy navigational aid and a dependable source of water for the first leg of any westward journey.

The Platte River corridor eventually became the primary avenue of transcontinental travel in the United States, a route so straightforward that it was used simultaneously by several of the most popular pioneer trails of the era. All emigrants traveling by the Oregon or California Trails followed the Great Platte River Road for hundreds of miles. There was a prevailing opinion that the north side of the river was healthier,[citation needed] so most Latter-day Saints generally stuck to that side, which also separated them from unpleasant encounters with former enemies, particularly non-Mormon emigrants from Missouri or Illinois. In the years of 1849, 1850 and 1852, traffic was so heavy along the corridor that virtually all feed for grazing livestock was stripped from both sides of the river. The lack of food and the threat of disease made the journey a deadly gamble.[4] An estimated 250,000 travelers made use of the Great Platte River Road during its peak years of 1841 to 1866. The Great Platte River Road was also used by the Pony Express, eventually becoming an important freight and military route.

Aside from the typical hazards of overland travel, ongoing conflict with Native Americans of the Great Plains also threatened migrants on the route. Following attacks in the spring and summer of 1864 by the Colorado Volunteers on the Cheyenne and other Plains Indians, a state of war developed along the South Platte, with numerous raids on stage stations, ranches and freighters along the road. After the Sand Creek massacre, the settlement of Julesburg, Colorado was attacked in January 1865, and again in February.[5]

Traditional modes of travel along the road declined with the completion of the First transcontinental railroad in 1869, which followed much of the same route through Nebraska.[6] The route has remained an important travel corridor in the modern era, being the path of choice for the transcontinental Lincoln Highway beginning in 1913 and eventually Interstate 80.

Points of interest along the route

editNebraska

edit- Fort Kearny (469 miles (755 km) west) — This fort, named after Stephen Watts Kearny, was established in June 1848. Another fort named after Kearny was established in May 1846 but quickly abandoned in May 1848. The second Fort Kearny is therefore sometimes called "New" Fort Kearny. The site for the fort was purchased from Pawnee Indians for $2,000 in goods.[7]

- Confluence Point (563 miles (906 km) west) — On May 11, 1847, three-fourths of a mile north of the confluence of the North and South Platte rivers, a "roadometer" was attached to Heber C. Kimball's wagon driven by Pilo Johnson. Although they did not invent the device, the measurements of the version they used were accurate enough to be used by William Clayton in his famous Latter-day Saints' Emigrants' Guide.[8]

- O'Fallon's Bluff — One of the most treacherous stretches of the road was O'Fallons Bluff, near Sutherland. There the South Platte River cut directly against the bluff and made it necessary to travel a narrow roadway over the bluffs. Deep sand that caught wagon wheels and threats of attacks by marauding bands of Native Americans presented challenges. Referred to in many pioneer traveler journals, during the years 1858 to 1860, there was a trading post, stage station and post office near O'Fallon's Bluff. By 1866, troops sent to protect the wagon trains from ambush had established Fort Heath nearby. In 1867, the O'Fallon's railroad siding, depot and post office were built north of the river opposite the bluff, along with a trading post and saloon.[9]

- Ash Hollow (646 miles (1,040 km) west) — Many passing diarists noted the beauty of Ash Hollow, although this was ruined by thousands of passing emigrants. Sioux Indians were often present at the site and General William S. Harney's troops won a battle over the Sioux there in September 1855, the Battle of Ash Hollow. The site is also the burial ground of many who died of cholera during the gold rush years.[10]

- Chimney Rock (718 miles (1,156 km) west) — Chimney Rock is perhaps the most significant landmark on the Mormon Trail. Emigrants commented in their diaries that the landmark appeared closer than it actually was, and many sketched or painted it in their journals and carved their names into it.[11]

- Scotts Bluff (738 miles (1,188 km) west) — Hiram Scott was a Rocky Mountain Fur Company trapper abandoned by his companions on the bluff that now bears his name when he became ill. Accounts of his death are noted by almost all those who kept journals that traveled on the north side of the Platte. The grave of Rebecca Winters, a Latter-day Saint mother who fell victim to cholera in 1852, is also located near this site, although it has since been moved and re-dedicated.[12]

A photo of the former overland trails, with historic trails marker, through Mitchell Pass at Scotts Bluff National Monument.

Wyoming

edit- Fort Laramie (788 miles (1,268 km) west) — This old trading and military post served as a place for emigrants to rest and re-stock provisions. The 1856 Willie Handcart Company was unable to obtain provisions at Fort Laramie, contributing to their subsequent tragedy when they ran out of food while encountering blizzard conditions along the Sweetwater River.[13][14]

- Upper Platte/Mormon Ferry (914 miles (1,471 km) west) — The last crossing of the Platte River took place near modern Casper. For several years, the Latter-day Saints operated a commercial ferry at the site, earning revenue from the Oregon- and California-bound emigrants. The ferry was discontinued in 1853 after a competing toll bridge was constructed. On October 19, 1856, the Martin Handcart Company forded the freezing river in mid-October, leading to exposure that would prove fatal to many members of the company.[15][16]

- Red Butte (940 miles (1,513 km) west) — Red Butte was the most tragic site of the Mormon Trail. After crossing the Platte River, the Martin Handcart Company camped near Red Butte as heavy snow fell. Snow continued to fall for three days, and the company came to a halt as many emigrants died. For nine days the company remained there, while 56 persons died from cold or disease. Finally, on October 28, an advance team of three men from the Utah rescue party reached them. The rescuers encouraged them that help was on the way and urged the company to start moving on.[17]

- Sweetwater River (964 miles (1,551 km) west) — From the last crossing of the Platte, the trail heads directly southwest toward Independence Rock, where it meets and follows the Sweetwater River to South Pass. To shorten the journey by avoiding the twists and turns of the river, the trail includes nine river crossings.[18][19]

Roadside settlements

editThe ranches and towns that settled alongside the road provided outfitters from Missouri River towns places to sell their wares, and gave pioneers resting areas along the route. The following settlements appeared east to west along the Great Platte River Road in the Nebraska Territory.[20]

- Hook

- Fort Kearny

- Dobytown

- Platte

- 17 Mile

- Hopeful

- Craig

- Blondeau

- Thomas

- Freeman

- Mullaley

- Pinniston and Miller

- Midway

- Gilman

- Clark

- Machete

- McDonald

- Post Cottonwood

- Box Elder

- Cold Springs

- Bishop

- Fremont's Springs

- O'Fallon

- Williams

- Moore

- Alkali

- Sandhill

- Diamond Springs

- Beauvais

- Bueller

- Julesburg

- Camp Rankin

Conjoining routes

editTrails, rails and highways that overlapped with or connected to the Great Platte River Road include:

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Mattes, M. (1987) The Great Platte River Road. University of Nebraska Press. p 6.

- ^ "More About the Great Platte River Road"[usurped], Nebraska State Historical Society. Retrieved 2008-03-28.

- ^ Mattes, M. (1987) The Great Platte River Road. University of Nebraska Press. Chapter VII.

- ^ The Pioneer Story. churchofjesuschrist.org. Retrieved 2006-05-22.

- ^ Pages 149 to 203 The Fighting Cheyenne, George Bird Grinnell, University of Oklahoma Press (1956 original copyright 1915 Charles Scribner's Sons), hardcover, 454 pages

- ^ Olson, J.C. and Naugle, R.C. (1997) History of Nebraska. University of Nebraska Press. p64.

- ^ "The Pioneer Story / Trail Location / Fort Kearny". churchofjesuschrist.org. Retrieved 2006-05-24.

- ^ "The Pioneer Story / Trail Location / Confluence Point". churchofjesuschrist.org. Retrieved 2006-05-29.

- ^ "Great Platte River Road"[usurped], Nebraska State Historical Society. Retrieved 2008-03-30.

- ^ "The Pioneer Story / Trail Location / Ash Hollow". churchofjesuschrist.org. Retrieved 2006-05-30.

- ^ "The Pioneer Story / Trail Location / Chimney Rock". churchofjesuschrist.org. Retrieved 2006-05-30.

- ^ "The Pioneer Story / Trail Location / Scotts Bluff". churchofjesuschrist.org. Retrieved 2006-05-30.

- ^ Hafen & Hafen (1992), p. 101

- ^ "The Pioneer Story / Trail Location / Fort Laramie". churchofjesuschrist.org. Retrieved 2009-06-18.

- ^ Hafen & Hafen (1992), pp. 108–109

- ^ "The Pioneer Story / Trail Location / Upper Platte (Mormon) Ferry". churchofjesuschrist.org. Retrieved 2009-06-18.

- ^ Hafen & Hafen (1992), pp. 110–115

- ^ "The Pioneer Story / Trail Location / Sweetwater River". churchofjesuschrist.org. Retrieved 2009-06-18.

- ^ "Ninth Crossing of the Sweetwater (Burnt Ranch)". Wyoming State Historic Preservation Office. Archived from the original on 2009-05-23. Retrieved 2009-06-18.

- ^ Becher, R. (1999) Massacre Along the Medicine Road: A Social History of the Indian War. Caxton Press. p 246.

Works cited

edit- Hafen, Leroy; Hafen, Ann (May 1992). Handcarts to Zion. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-7255-3.