José Gonzalo Rodríguez Alvarez Gacha (14 May 1947 – 15 December 1989), also known by the nicknames Don Sombrero (English: Mister Hat) and El Mexicano (English: The Mexican), was a Colombian drug lord who was one of the leaders of the Medellín Cartel along with the Ochoa brothers and Pablo Escobar. At the height of his criminal career, Rodríguez was acknowledged as one of the world's most successful drug dealers. In 1988, Forbes magazine included him in their annual list of the world's billionaires.[1]

José Gonzalo Rodríguez Alvarez Gacha | |

|---|---|

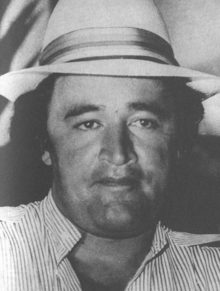

Picture of Rodriguez Alvarez Gacha | |

| Born | 14 May 1947 |

| Died | 15 December 1989 (aged 42) Tolú, Colombia |

| Cause of death | Gunshots |

| Nationality | Colombian |

| Other names | Don Sombrero (Mister hat),El Mexicano (The Mexican) |

| Criminal status | Deceased |

| Spouse | Gladys Álvarez Pimentel |

| Children | 2 |

Early years

editJosé Gonzalo Rodríguez Gacha was born in May 1947 in the small town of Veraguas, near Pacho in the department of Cundinamarca. He came from a poor family of cheese vendors,[2][3] and it is said that his formal education did not extend beyond grade school. He left school in the early 1970s and moved to Muzo, Boyacá, the center of the emerald exploitation in Colombia. There he began to work under Gilberto Molina Moreno, who at the time was called the "tsar" of emeralds in Boyacá, as part of his security, developing a fearsome reputation as a killer. As he started to go up in the ranks among Molina's men, he also became acquainted with drug traffickers. At some point, Rodríguez Gacha decided that the drug business was more profitable and became independent. He moved to Bogotá and became associated up with Verónica Rivera de Vargas, a pioneering drug trafficker who was known as the "queen of cocaine," by murdering the family of her main rival.[4] Rivera introduced him to Pablo Escobar and to Mexican drug lord, Miguel Ángel Félix Gallardo.[5]

Rise of the Medellín Cartel

editAs he started to prosper in the drug trafficking business, Rodríguez Gacha started to buy larger amounts of land in the Middle Magdalena region in the valley bordering the departments of Antioquia, Boyacá, and Santander.[6] After moving to Medellín in 1976, Rodríguez Gacha associated with the Ochoa family, Pablo Escobar, and Carlos Lehder in establishing an alliance that eventually strengthened into what would become known as the Medellín Cartel. The traffickers cooperated in the manufacturing, distribution and marketing of cocaine. During the late 1970s, Rodríguez advanced in the organizational hierarchy, pioneering new trafficking routes through Mexico and into the United States, primarily Los Angeles, California and Houston, Texas. He is often said to have been the first to establish cooperation strategies with drug trafficking cartels in Mexico.[5] This, coupled with his infatuation with Mexican popular culture, music, and horse culture, and his fondness for foul language, earned him the nicknames El Mexicano (the Mexican) and 'Don Sombrero'. He owned a string of farms in his hometown in the locality of Pacho with Mexican inspired names such as Cuernavaca, Chihuahua, Sonora and Mazatlán.[5]

According to the US Justice Department, Rodríguez directed cocaine trafficking operations through Panama and the West Coast (California) of the United States. It is claimed that he helped design a Nicaraguan trafficking operation that employed pilot Barry Seal (who was murdered on February 19, 1986, after agreeing to testify against the Medellín Cartel).[citation needed]

Rodríguez Gacha based much of his operations from Bogotá and other areas in the Cundinamarca region, as well as in the Middle Magdalena region. It was Rodríguez who first set up Tranquilandia, one of the largest and best known of the jungle laboratories where more than two thousand people lived and worked making and packaging cocaine. ["The Accountant's Story", by Roberto Escobar].

As he became one of the main capos of the rising Cartel, Rodríguez Gacha started having problems with the FARC guerrilla, mostly derived from the fact that the insurgent army taxed some of his coca plantations, and that they sometimes robbed some of his men.[7] When the M-19 guerrilla kidnapped Martha Nieves Ochoa, the sister of fellow drug lord Jorge Luis Ochoa, the cartel decided to create what would be one of the first far-right paramilitary groups to fight the guerrillas, the "Muerte a Secuestradores" (MAS) [Death to Kidnappers] movement. Rodríguez Gacha became one of the main economic supporters of the group. He soon became the de facto military leader of the cartel and thanks to his immense riches, he managed to form the largest paramilitary organization in the country, composed of around 1,000 men, all trained and armed, originally devoted to his security but soon becoming an anti-communist army directed particularly against the FARC, and then against the Unión Patriótica political party.[6][7]

Lara assassination

editOn March 7, 1984, the Colombian Police and the DEA destroyed Rodríguez Gacha's Tranquilandia complex.[5] A few weeks later, on April 30, 1984, Colombian Minister of Justice Rodrigo Lara, who had crusaded against the Medellin Cartel, was assassinated by armed men on a motorcycle. In response, President Belisario Betancur, who had previously opposed extradition, made an announcement that "we will extradite Colombians." Carlos Lehder was the first to be put on the list. The crackdown forced the Ochoas, Escobar and Rodríguez to flee to Panama for several months. A few months later, Escobar was indicted for Lara's murder and Rodríguez was named as a material witness. In an attempt to handle the situation, Escobar, Rodríguez and the Ochoa brothers met with the former Colombian president Alfonso López in the Hotel Marriott in Panama City. The negotiation failed after news of it leaked to the press, provoking the open opposition of the United States to any immunity deal.[8]

Cartel-linked paramilitary groups

editParamilitary groups (or self-defense groups, autodefensas as they are frequently referred to in Colombia), were created with the support of landowners and cattle ranchers who had been under pressure from the guerrillas as well as from groups affiliated with narcotics traffickers such as the Muerte a Secuestradores movement (MAS – Death to Kidnappers). As made clear in a 2004 judgment of the Inter-American court of Human Rights,[9] numerous independent reports and from what the paramilitaries themselves have said, in at least some cases they were given support by the state itself.[10] The top leaders of the Medellín Cartel created private armies to guarantee their own security and protect the property they had acquired. According to The Washington Post, in the mid-1980s, Rodríguez and Pablo Escobar bought huge tracts of land in the Magdalena Department (as well as Puerto Boyacá, Rionegro and the Llanos) which they used to transform their self-defense groups from poorly trained peasant militias into sophisticated fighting forces.[11] By the late 1980s Medellin traffickers controlled 40% of the land in the Middle Magdalena, according to a Colombian military estimate, and also funded most of the paramilitary operations in the region.

Throughout the 1980s, Rodríguez helped catalyze the Medellín Cartel's explosive rise to power by financing the importation and implementation of expensive foreign technology and expertise. According to the report by the Departamento Administrativo de Seguridad (Colombia's Administrative Security Department), between December 1987 and May 1988, Rodríguez hired Israeli and British mercenaries to train teams of assassins at remote training camps in Colombia. Yair Klein, a retired Israeli lieutenant colonel, acknowledged having led a team of instructors in Puerto Boyacá in early 1988.[12] It is not clear whether Klein's mercenary activities in Colombia coincided with those of a group of British mercenaries who had allegedly trained paramilitary squads for the cocaine cartels.[13]

American fight against drugs

editBy 1989, the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) estimated that 80 percent of cocaine consumed in the United States was imported from Colombia by the Medellín Cartel and its rival, the Cali Cartel. The newly elected administration of President George H. W. Bush was under considerable pressure to combat the increasing drug usage and drug-related violence plaguing scores of American cities. Much of the government strategy concentrated on restricting drug supply by extraditing Colombian cartel leaders to the United States for prosecution. On August 21, 1989, Attorney General Dick Thornburgh released a list of the twelve Colombian drug kingpins (commonly referred to as the "dirty dozen") most wanted by the United States and said the names would be shared with the Colombian government and Interpol. The list included Pablo Escobar, Jorge Luis Ochoa, and José Gonzalo Rodríguez, the leading members of the Medellín Cartel.

Financial crackdown

editPresident Bush declared money laundering a critical target in the war on drugs, allocating $15 million to launch a counteroffensive. Only hours after Bush unveiled his antidrug offensive in September 1989, a federal task force began taking shape. The Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FINCEN) was designed to zero in on money launderers with computer programs capable of spotting suspicious movements of electronic money. On December 6, 1989, Attorney General Dick Thornburgh announced that authorities had frozen accounts in five countries holding $61.8 million belonging to Rodriguez Gacha. According to the Justice Department, the money represented long-term high-yield stocks and investments and was held in bank accounts in England, Switzerland, Austria, Luxembourg and the United States. An additional $20 million of Gacha's drug money was suddenly transferred to Panama, where it was protected from American authorities.[14]

Rodríguez Gacha's final years

editThe growth of Rodríguez Gacha's criminal empire had allowed him to increase his fortune but also made him a lot of enemies. By 1987, animosity started with the Cali Cartel, his previous partners in MAS, as he attempted to move in on the New York City market. The animosity turned into an open cartel war in 1988, moved mostly by the personal vendetta of Pablo Escobar against Pacho Herrera. As the military leader of the cartel, Rodríguez Gacha was instrumental in many assassinations and other violent actions against the Cali Cartel.

Furthermore, he was already in an open war against the FARC guerrilla and he was already in a crusade against the Colombian government and the DEA. His push to join his properties in his hometown in Pacho with his many lands in the middle Magdalena region soon put him in conflict with his old allies in the emerald business, as the emerald region of Muzo was in between.[7] To ensure his dominion on the land, Rodríguez Gacha became involved in an intense and violent power struggle over control of the emerald mines. On February 27, 1989, he directed a group of 25 gunmen to kill emerald magnate Gilberto Molina, his former boss, who was previously considered among his close associates, along with sixteen other individuals at a party in Molina's home.[6] Then he went after his former associate Verónica Rivera, the "queen of cocaine," who was killed in Bogota by hitmen under his command, on July 1, 1989.[15] Later, he detonated a bomb in the offices of Tecminas in Bogotá, which were property of Victor Carranza, the new emerald tsar, whose nephew's murder he also ordered.[16]

El Mexicano or 'Don Sombrero' was later charged in Colombia and the United States for his involvement in a number of killings, including the assassination of the president of the leftist Patriotic Union party, Jaime Pardo Leal on October 12, 1987, in retaliation for guerrilla attacks on drug traffickers in the eastern plains area known as the "llanos orientales".[17] Rodriguez Gacha starts the 1989 (year of horror in Colombia) massacring 12 judicial officials to allegedly remove them the judicial files. Pablo Escobar and Rodríguez contracted trained hitmen by Jair Klein for the slaying of popular presidential candidate Luis Carlos Galán on August 18, 1989, who was considered likely to be elected Colombia's next president. After the murder of Galán, "Don Sombrero" had begun to have a less active role in the terrorist attacks of the Medellin cartel.[6]

Government crackdown and narcoterrorism

editIn response to a wave of drug-related assassinations, Colombian President Virgilio Barco launched an all-out offensive on the cocaine cartels and re-established extraditions with the United States. At first, the Colombian public overwhelmingly backed Barco's crackdown, which was announced hours after the assassination of Galán on August 18. The government made quick and unprecedented strides against the traffickers - seizing expensive homes, ranches, airfields, cocaine processing labs and large amounts of cash and drugs. Authorities conducted raids throughout the country and made thousands of arrests. The Medellin Cartel responded by declaring "war" on the government, and over the next four months, bombings became an almost daily occurrence and scores of people died.

By October 1989, public support for the crackdown was beginning to wane and the government decided to focus its attention on capturing either Pablo Escobar or Rodríguez. However, both men managed to stay one step ahead of law enforcement and continued to finance a campaign of retaliatory terrorism which claimed the lives of hundreds of politicians, judges and civilians. Colombian authorities said that Rodriguez Gacha and Pablo Escobar planned the December 7, 1989 bombing of the secret investigative police headquarters in Bogotá which killed 63 people and injured an estimated 1,000. The two men were also accused of involvement in the November 27, 1989 bombing of Avianca Flight 203 outside Bogotá that killed all 107 people aboard.

Death

editAt the time of his death, Rodríguez Gacha was fighting wars simultaneously against the Colombian government, the Cali cartel, the FARC guerrillas, the DEA, and the emerald businessmen led by Víctor Carranza. All of them began collaborating to bring him down.[7][16] His organization was infiltrated by the Cali cartel, Carranza and the emerald guild were also providing intelligence reports.[6] In August 1989, the Colombian Government caught a break when Rodríguez Gacha's son, Freddy Rodriguez Celades, was arrested during an army raid of one of Rodriguez Gacha's ranches in the north of Bogotá. Freddy's alleged crime, possession of illegal weapons, was relatively minor but police held him longer than most unindicted prisoners, hoping to put pressure on Rodríguez. When no signs of fatherly concern emerged, the police released Freddy and waited.

Jorge Velásquez (alias "El Navegante"), an informant placed by the Cali Cartel into Gacha's organisation who was allegedly seeking the government reward, revealed to the police that the drug lord was in Cartagena de Indias protected by 25 bodyguards.[18] When the police arrived there, Gacha fled to Tolú by motorboat. At the destination, the drug lord was accompanied by his son Freddy, Gilberto Rendón Hurtado (alias "mano de yuca" – the alleged No. 8 man in the Medellín Cartel and who had then control over the network to transport cocaine from the Caribe Coast), four bodyguards and El Navegante. El Navegante again gave information on Gacha's location to the police after he left in the evening on December 14, 1989. With this new information, the police intercepted his motorboat and placed him on one of the two Colombian military helicopters prepared for the offensive.[19][20]

At noon on December 15, 1989, twenty-two policemen (seventeen of whom were from the elite police) boarded the two artillery helicopters and flew over El Tesoro, a village between Coveñas and Tolú where the police were told that the target was hidden. By talking through a loudspeaker, the police demanded that Rodríguez Gacha surrender, but Gacha and his men, disguised as farm workers, waited for the police to withdraw. Still, the two helicopters kept flying over the zone. When the fugitives got an opportunity, they ran to a red truck parked near the village and drove away, and were pursued by the police.[19][20]

After several unsuccessful attempts to escape from the police, Freddy Gonzalo (armed with a 9 mm pistol), Gilberto Rendón and three other bodyguards got off the truck and, while running towards a group of trees, engaged in a shootout with one of the aircraft, during which two of the fugitives were killed by a burst of the helicopter-mounted machine gun. The helicopter then landed; 5 elite policemen engaged in another shootout with the remaining fugitives, two bodyguards and Freddy Gonzalo, eventually killing them.[19][20]

Meanwhile, the other helicopter was chasing the truck with Gacha and one of his men inside. When another police patrol appeared ahead on the road, Gacha and his bodyguard stopped the truck, got out of it and ran away into a banana plantation on the side of the road. The artillerymen opened fire to try to detect the fugitives's whereabouts on the plantation. Gacha, armed with a German submachine gun, slowed his pace when he tore his scalp while trying to get through a wire fence. Feeling cornered, he fired his submachine gun at the aircraft, which revealed his whereabouts. As a response, the police fired a burst of the helicopter-mounted machine gun at him, wounding him in one of his legs and making him fall. He was then shot in the face, killing him. His last bodyguard was killed shortly afterwards.[19][20]

Neighbours deduced from the sound of grenades and the damage to his face that El Mexicano had died by suicide by detonating a grenade against his head. However, police confirmed that he had died from a bullet, citing the destructive effect of a large-caliber bullet and the fact that El Mexicano's hands were not damaged, which would have been the case if he had detonated a grenade.[21]

Funeral

editThousands of mourners thronged the streets of the town of Pacho for Rodriguez Gacha's funeral on Sunday, December 17, 1989. Residents of Pacho said he donated money to renovate buildings, and some viewed him as a public benefactor. About 3,000 people surrounded the cemetery because access to the funeral was limited to relatives. A newspaper estimated the number of mourners as high as 15,000.[22]

In popular culture

edit- In the TV series Escobar, el Patrón del Mal, Rodriguez Gacha is portrayed by the Colombian actor Juan Carlos Arango as the character Gustavo Ramirez Rocha "El Mariachi".

- In 2013 TV Series Tres Caínes, Rodríguez Gacha is portrayed by the Colombian actor Rodolfo Silva (who portrayed Roberto Escobar in the previous series) as the character of Gonzalo Mahecha.

- In the 2015 TV thriller-drama series Narcos, produced by Netflix, Rodriguez Gacha is portrayed by Luis Guzmán. Narcos follows drug kingpin Pablo Escobar (played by Brazilian actor Wagner Moura), as well as the ruthless Medellín Cartel.

- In the 2013 based on a true story TV series Alias El Mexicano, Gonzalo Rodriguez Gacha is portrayed by Colombian actor Juan Sebastián Calero. Calero has portrayed before a younger version of Gustavo Gaviria in Escobar, el patrón del mal. Calero reprises his role in TV Series Diomedes, el cacique de la junta.

- In the 2016 TV series Bloque de búsqueda is portrayed by the Colombian actor Elkin Díaz as the character of Gonzalo Rodríguez Largacha.

- In the same year 2016, Rodríguez Gacha is portrayed by the Colombian actor Andrés Soleibe in TV Series En la boca del lobo as the character of Jaime Gonzalo Ramírez Lacha.

- In the 2019 TV Series El General Naranjo, Rodríguez Gacha is portrayed by the Colombian actor Walter Luengas.

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ U.S. Congress, Office of Technology AssessmentInformation Technologies for the Control of Money Laundering OTA-ITC-630, Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, September 1995

- ^ https://www.kienyke.com/historias/tras-los-rastros-de-gacha

- ^ https://www.infobae.com/america/mexico/2019/05/15/el-mexicano-el-despiadado-narco-que-festejaba-con-mariachis-y-se-unio-a-pablo-escobar/

- ^ 'Drug Kingpin 'El Mexicano' or 'Don Sombrero' Is Violent Empire-Builder : 40-Year-Old a Symbol of Cocaine Wealth'. The Washington Post, November 14, 1987

- ^ a b c d "Le decían 'El Mexicano'; fue pionero de alianza de capos [Capos] - 05/01/2014 | Periódico Zócalo". www.zocalo.com.mx. Archived from the original on 2015-07-24. Retrieved 2017-01-26.

- ^ a b c d e "El otro capo que ensangrentó a Colombia". ElEspectador. Retrieved 2017-01-26.

- ^ a b c d "EL FIN DE 'EL MEXICANO'". www.semana.com. 8 June 1992. Retrieved 2017-01-26.

- ^ Alonso Salazar J, La Parábola de Pablo: Auge y caída de un gran capo del narcotráfico (Santafé de Bogotá: Editorial Planeta, 2001), pp. 129-131.

- ^ See the Judgement of the Court of July 5, 2004 in the Case of 19 Merchants, paragraphs, 84a-84d

- ^ In the speech, the Magdalena Medio commander present at the Congress of the Republic on July 28, 2004, he said: “we went to Base Calderón, now the Barbula battalion, we stated what we wished to do and they helped us with 8 shotguns and munitions…and then on February 18, 1978, the now Peasant Self Defence of the Magdalena Medio Antioqueno were both.”

- ^ Doug Farah, "Massacres Imperil U.S. Aid to Colombia Paramilitary Groups Linked to Army, The Washington Post, January 31, 1999, A01

- ^ Colombian Security Alleges Mercenary Aid to Cartels. August 29, 1989, Washington Post Foreign Service

- ^ Tony Thompson, ‘High-tech Crime of the Future Will be all Mod Cons’, The Observer, October 3, 1999, The Omega Foundation (Manchester, UK) carried out a study of new security technologies for the Scientific and Technological Options Assessment Panel at the request of the Committee on Civil Liberties and Internal Affairs of European Parliament in January 1998

- ^ Jonathan Beaty and Richard Hornik, "A Torrent of Dirty Dollars", Time magazine, Posted June 24, 2001

- ^ "Asesinada la 'reina de la coca'". EL PAÍS (in Spanish). 1989-07-02. Retrieved 2017-01-26.

- ^ a b "Ha muerto el zar, el zar ha muerto: el funeral de Víctor Carranza - Las2orillas". Las2orillas (in European Spanish). 2013-06-13. Retrieved 2017-01-26.

- ^ "Drug Kingpin 'El Mexicano' Is Violent Empire-Builder: 40-Year-Old a Symbol of Cocaine Wealth", November 14, 1987, The Washington Post

- ^ https://www.semana.com/especiales/articulo/el-fin-de-el-mexicano/17554-3/

- ^ a b c d Alonso Salazar J, La Parábola de Pablo: Auge y caída de un gran capo del narcotráfico (Santafé de Bogotá: Editorial Planeta, 2001), pp. 473-475.

- ^ a b c d ""El Mexicano": contra todo y contra todos" (in Spanish). Editorial El Tiempo. 17 December 1989. Retrieved 24 February 2018.

- ^ "La cacería final contra Rodríguez Gacha" (in Spanish). Editorial El Tiempo. 17 December 1989. Retrieved 4 October 2015.

- ^ 'Hometown Mourns Colombian Drug Dealer'. December 19, 1989 The New York Times