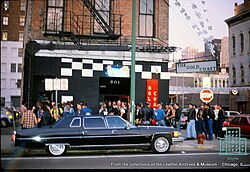

Gold Coast was a leather bar for gay men in Chicago that operated from 1960 to 1988. It was one of the first bars created by and for the gay leather community in the United States.[1][2][3] For most of its 28 year history, between 1967 and 1984, the bar was located at 501 North Clark Street adjacent to Chicago's Gold Coast neighborhood.[4] This was also the period of its legendary basement, called The Pit. It was one of several gay businesses owned and operated by Chuck Renslow.[2] The bar's founding led to the establishment of other gay businesses nearby, creating a kind of "gay district" in the area.[5]

| Gold Coast | |

|---|---|

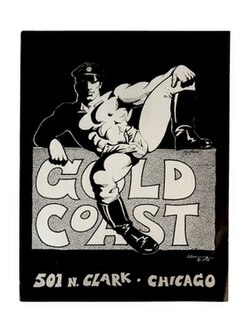

Logo designed by Etienne | |

| |

| |

| General information | |

| Type | Gay bar, Leather bar |

| Address | 501 N Clark Street, Chicago, IL |

| Coordinates | 41°53′28″N 87°37′51″W / 41.891011°N 87.630811°W |

| Opened | 1960 |

| Relocated | 1962, 1965, 1967, 1984 |

| Closed | 1988 |

| Owner | Chuck Renslow |

History

editThe original location of the then-named Gold Coast Show Lounge was 1130 North Clark Street. A group of Chicago leathermen, including Chuck Renslow and Dom Orejudos, had been meeting there regularly as patrons since 1959. After the death of the original owner in the same year, his son offered the bar for sale. Renslow, Herbie Schmidt and Art Marotta bought the bar so as not to lose the meeting place for the emerging gay leather scene.[6]

The bar opened under the new shortened name Gold Coast on March 15, 1960. After a significant rent increase, the bar moved to 1110 North Clark Street in 1962.[7] There, the bar had a "2 am" liquor license which permitted it to serve alcohol but required it to close by 2 am.

In 1965, the bar moved to 2265 North Lincoln Avenue; it relocated to 501 North Clark Street in 1967.[8][9]

The bar was known for its "hardcore" leather culture,[10] and did not pay for a dancing license because the owners felt their clientele would not be interested in dancing.[11] Renslow paid bribes to police to prevent the bar from being raided, although this still occurred occasionally.[12]

Dom Orejudos (widely known by his alias "Etienne"), who was Renslow's partner,[13] created numerous posters and artworks for the Gold Coast.[14] Together with Chuck Arnett, Orejudos also created the bar's famous murals.[14][15] Renslow donated much of this art to the Leather Archives & Museum, some of which is on display in the museum's auditorium.[16][17]

1969, a leather and sex toy shop opened in the bar's basement, selling hankies, leather goods like harnesses, vests, slings and chaps, as well as sex toys, called the Leather Cell. It later became Male Hide Leathers, one of the first gay leather shops.[18]

From 1972 on, the bar hosted an annual "Mr. Gold Coast" pageant, with John Lunning as the first winner.[19] In 1979, the contest was rebranded as International Mr. Leather, which continues to this day.[20][21] In 1984, the bar relocated to 5025 N Clark Street in Andersonville;[9] it was sold one year later to Frank Kellas in exchange for stocks of the GayLife newspaper.[22][23] The bar closed permanently on February 10, 1988, after its liquor license was revoked. Prior to this, it had declined in popularity due in part to the relocation and to changes in management.[22]

Cultural impact and legacy

editAccording to Dazed, "the importance of bars like the Gold Coast stemmed from more than mere fetish; LGBTQ+ communities have always had their sex lives heavily policed and often criminalised. This wasn’t just about fetish or fucking – in a pre-Stonewall age in particular, these rare spaces were about freedom."[24]

On May 25, 2018, the Chicago City Council voted to designate the eastern stretch of Clark Street between Winnemac Ave and Ainslie Ave—the historic location of the Gold Coast, Man's Country, and other businesses owned by Renslow—as "CHUCK RENSLOW WAY."[25][26]

References

edit- ^ "Remembering Chicago Leatherman Chuck Renslow". WBEZ Chicago. 2017-06-30. Retrieved 2023-10-01.

- ^ a b Goldsborough, Bob (2017-06-30). "Chuck Renslow, Chicago gay community icon and International Mr. Leather contest founder, dies at 87". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 2023-10-01.

- ^ "A Conversation About Chicago's Boystown". WBEZ Chicago. 2017-06-18. Retrieved 2023-10-01.

- ^ "Our History". Man's Country Chicago. Retrieved 2023-10-01.

- ^ Baim, Tracy; Keehnen, Owen; Kelley, William B.; Harper, Jorjet (2011). Leatherman: the legend of Chuck Renslow (1st ed.). Chicago: Prairie Avenue Productions. pp. 125–128. ISBN 978-1-4610-9602-3. OCLC 728063271.

- ^ Baim, Tracy; Keehnen, Owen; Kelley, William B.; Harper, Jorjet (2011). Leatherman: the legend of Chuck Renslow (1st ed.). Chicago: Prairie Avenue Productions. pp. 88–89. ISBN 978-1-4610-9602-3. OCLC 728063271.

- ^ Baim, Tracy; Keehnen, Owen; Kelley, William B.; Harper, Jorjet (2011). Leatherman: the legend of Chuck Renslow (1st ed.). Chicago: Prairie Avenue Productions. pp. 89–91. ISBN 978-1-4610-9602-3. OCLC 728063271.

- ^ Baim, Tracy; Keehnen, Owen; Kelley, William B.; Harper, Jorjet (2011). Leatherman: the legend of Chuck Renslow (1st ed.). Chicago: Prairie Avenue Productions. pp. 98–101. ISBN 978-1-4610-9602-3. OCLC 728063271.

- ^ a b Croix, Sukie de la (2003-05-21). "International Mr. Leather Hits 25th Anniversary". Windy City Times. Retrieved 2024-07-03.

- ^ Wagner, R. Richard (2020-05-22). Coming Out, Moving Forward: Wisconsin's Recent Gay History. Wisconsin Historical Society. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-87020-928-4.

- ^ Baim, Tracy; Keehnen, Owen; Kelley, William B.; Harper, Jorjet (2011). Leatherman: the legend of Chuck Renslow (1st ed.). Chicago: Prairie Avenue Productions. pp. 128–130. ISBN 978-1-4610-9602-3. OCLC 728063271.

- ^ Stewart-Winter, Timothy (2016-02-16). Queer Clout: Chicago and the Rise of Gay Politics. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-8122-4791-6.

- ^ Baim, Tracy; Keehnen, Owen; Kelley, William B.; Harper, Jorjet (2011). Leatherman: the legend of Chuck Renslow (1st ed.). Chicago: Prairie Avenue Productions. ISBN 978-1-4610-9602-3. OCLC 728063271.

- ^ a b Lock, Jack. "Dom Orejudos aka "Etienne"". Visual AIDS. Retrieved 2023-10-01.

- ^ Evans Frantz, David. "Dress Codes: Chuck Arnett & Sheree Rose". ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives at the USC Libraries. Retrieved 2024-07-08.

- ^ "The Etienne Auditorium". Leather Archives & Museum. Archived from the original on 2023-11-29. Retrieved 2023-10-01.

- ^ Keehnen, Owen (2016-05-25). "Leather Archives & Museum turns 25". Windy City Times. Retrieved 2023-10-01.

- ^ Baim, Tracy; Keehnen, Owen; Kelley, William B.; Harper, Jorjet (2011). Leatherman: the legend of Chuck Renslow (1st ed.). Chicago: Prairie Avenue Productions. p. 105. ISBN 978-1-4610-9602-3. OCLC 728063271.

- ^ Baim, Tracy; Keehnen, Owen; Kelley, William B.; Harper, Jorjet (2011). Leatherman: the legend of Chuck Renslow (1st ed.). Chicago: Prairie Avenue Productions. p. 109. ISBN 978-1-4610-9602-3. OCLC 728063271.

- ^ "Legendary Chicago businessman, activist Chuck Renslow dies - Windy City Times News". Windy City Times. 2017-06-29. Retrieved 2023-10-01.

- ^ "Chuck Renslow". Chicago Gay History. Retrieved 2023-10-01.

- ^ a b de la Croix, Sukie (2000-09-27). "Gary Chichester: A Remarkable Life". Windy City Times. Retrieved 2024-01-08.

- ^ Baim, Tracy; Keehnen, Owen; Kelley, William B.; Harper, Jorjet (2011). Leatherman: the legend of Chuck Renslow (1st ed.). Chicago: Prairie Avenue Productions. p. 129. ISBN 978-1-4610-9602-3. OCLC 728063271.

- ^ Hall, Jake (2018-02-21). "The pioneering gay erotica artist who inspired JW Anderson's new collection". Dazed. Retrieved 2024-07-14.

- ^ "Record No. O2018-3236". City of Chicago, Office of the City Clerk. Retrieved November 7, 2023.

- ^ "Chuck Renslow street dedication May 19 - Windy City Times News". Windy City Times. 2018-05-07. Retrieved 2023-11-08.