The goa (Procapra picticaudata), also known as the Tibetan gazelle, is a species of antelope that inhabits the Tibetan plateau.

| Goa | |

|---|---|

| |

| From North Sikkim, India | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Family: | Bovidae |

| Subfamily: | Antilopinae |

| Tribe: | Antilopini |

| Genus: | Procapra |

| Species: | P. picticaudata

|

| Binomial name | |

| Procapra picticaudata Hodgson, 1846

| |

| |

| Population range | |

Description

editThe goa is a relatively small antelope, with slender and graceful bodies. Both males and females stand 54 to 65 centimetres (21 to 26 in) tall at the shoulder, measure 91 to 105 cm (36 to 41 in) in head-body length and weigh 13 to 16 kg (29 to 35 lb). Males have long, tapering, ridged horns, reaching lengths of 26 to 32 cm (10 to 13 in). The horns are positioned close together on the forehead, and rise more or less vertically until they suddenly diverge towards the tips. Females have no horns, and neither sex has distinct facial markings.[2]

The goa is grayish brown over most of its body, with its summer coat being noticeably greyer in colour than its winter one. It has a short, black-tipped tail in the center of its heart-shaped white rump patches. Its fur lacks an undercoat, consisting of long guard hairs only, and is notably thicker in winter. It appears to have excellent senses, including keen eyesight and hearing.[2] Its thin and long legs enhance its running skills, which are required to escape from predators.

Distribution and habitat

editThe goa is native to the Tibetan plateau, and is widespread throughout the region, inhabiting terrain between 3,000 and 5,750 m (9,840 and 18,860 ft) in elevation. It is almost restricted to the Chinese provinces of Gansu, Xinjiang, Tibet, Qinghai, and Sichuan, with tiny populations in the Ladakh and Sikkim regions of India. No distinct subspecies of goa have been reported.[2]

Alpine meadow and high elevation steppe are the primary habitats of the goa. It is scattered widely across its range, being present in numerous small herds spread wide apart; estimates of population density vary from 2.8 individuals per sq km to less than 0.1, depending on the local environment.[2]

Behaviour and ecology

editUnlike some other ungulates, goas do not form large herds, and are typically found in small family groups. Although they occasionally gather into larger aggregations, most goa groups contain no more than 10 individuals, and many are solitary. They have been noted to give short cries and calls to alert the herd on approach of a predator or other perceived threat.[2]

Goas feed on a range of local vegetation, primarily forbs and legumes, supplemented by relatively small amounts of grasses and sedges. Their main local predators are the Himalayan wolf[3] and the snow leopard.[4]

Reproduction

editFor much of the year, the sexes remain separate, with the females grazing in higher altitude terrain than the males. The females descend from their high pastures around September, prior to the mating season in December. During the rut, the males are largely solitary, scent marking their territories and sometimes butting or wrestling rival males with their horns.

Gestation lasts around six months, with the single young being born between July and August. The infants remain hidden with their mother for the first two weeks of life, before rejoining the herd. The age of sexual maturity in goas is unknown, but is probably around 18 months. Goas have lived for up to five years and seven months in captivity.[2]

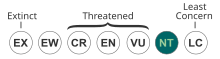

Conservation status

editAlthough goa populations have declined over recent years, they do not inhabit regions of high human population over most of their range, and do not significantly compete with local livestock. Because of their small size, they are not popular targets for hunting, and they are classified as a class II protected species in China. The primary threats to the goa in China are loss of habitat, due to encroachment on their natural ranges by pastoralists and the expansion of agriculture in the western provinces.[2]

In Ladakh, they live at high altitudes (4,750-5,050 m or 15,580-16,570 ft), but prefer relatively flat areas with an affinity for warmer, south-facing slopes. They coexist with domestic yaks and kiang, but are competitive with domestic goats and sheep and avoid herders and their dogs.[5] The population in Ladakh, less than 100 individuals, continues to decline. Within Ladakh, its distribution was spread as far west as the Tsokar Basin in the beginning of the 20th century, but today is confined to the Hanle Valley and the neighbouring areas, such as Chumur. Presently gazelles are suffering not only from poor pasture conditions, but also from problems associated with small populations such as lack of genetic diversity in the population, which makes them less resistant to diseases.[6]

Goa populations in both Ladakh and Tibet seem to be declining precipitously and are threatened with extinction, at least in some regions.[6][7] A small population also exists in northern Sikkim, right at the border between India and Chinese-controlled territories, apparently moving back and forth between the countries.[citation needed]

References

edit- ^ IUCN SSC Antelope Specialist Group (2017) [errata version of 2016 assessment]. "Procapra picticaudata". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T18231A115142581. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T18231A50192968.en. Retrieved 3 November 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g Leslie, D.M. Jr. (2010). "Procapra picticaudata (Artiodactyla: Bovidae)". Mammalian Species. 42 (1): 138–148. doi:10.1644/861.1.

- ^ Lyngdoh, S. B.; Habib, B.; Shrotriya, S. (2019). "Dietary spectrum in Himalayan wolves: comparative analysis of prey choice in conspecifics across high-elevation rangelands of Asia" (PDF). Down to Earth. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- ^ Lyngdoh, S.; Shrotriya, S.; Goyal, S. P., Clements, H.; Hayward, M. W.; Habib, B. (2014). "Prey preferences of the snow leopard (Panthera uncia): regional diet specificity holds global significance for conservation". PLOS ONE. 9 (2): e88349. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...988349L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0088349. PMC 3922817. PMID 24533080.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Namgail, Tsewang; S. Bagchi; C. Mishra; Y. Bhatnagar (2008). "Distributional correlates of the Tibetan gazelle in northern India: Towards a recovery programme". Oryx. 42 (1): 107–112. doi:10.1017/s0030605308000768.

- ^ a b Bhatnagar, Y.V.; Seth, C.M.; Takpa, J.; Ul-Haq, Saleem; Namgail, Tsewang; Bagchi, Sumanta; Mishra, Charudutt (2007). "A Strategy for Conservation of the Tibetan Gazelle Procapra picticaudata in Ladakh" (PDF). Conservation and Society. 5 (2): 262–276. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 10, 2008.

- ^ Rizvi, Janet. Ladakh: Crossroads of High Asia, p. 49. 1983. Oxford University Press. Reprint: Oxford University Press, New Delhi (1996)

External links

edit- "Procapra picticaudata - Images at ADW". Animal Diversity Web.