Gladys Amanda Reichard (born 17 July 1893 at Bangor, Pennsylvania; died 25 July 1955 at Flagstaff, Arizona) was an American anthropologist and linguist. She is considered one of the most important women to have studied Native American languages and cultures in the first half of the twentieth century. She is best known for her studies of three different Native American languages: Wiyot, Coeur d'Alene and Navajo.[1][2][3] Reichard was concerned with understanding language variation, and with connections between linguistic principles and underpinnings of religion, culture and context.

Gladys Reichard | |

|---|---|

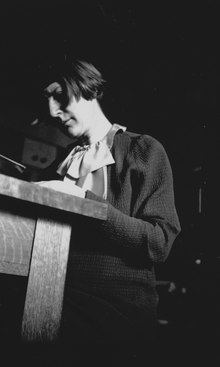

Gladys Amanda Reichard circa 1935 | |

| Born | 17 July 1893 |

| Died | 25 July 1955 |

| Awards | Guggenheim Fellowship |

| Academic background | |

| Alma mater | |

| Academic work | |

| Discipline | anthropology and linguistics |

| Sub-discipline | Native American languages and cultures |

| Institutions | Barnard College |

Biography

editReichard received her bachelor's degree from Swarthmore College in 1919 and her master's degree from the same institution in 1920.[4] She started fieldwork on Wiyot in 1922 under the supervision of A.L. Kroeber of the University of California-Berkeley.[4] Reichard attended Columbia University for her PhD, which she earned in 1925 for her grammar of Wiyot, written under Franz Boas.[4][5] Reichard's fieldwork on Wiyot was undertaken in 1922 to 1923 and resulted in the publication of Wiyot Grammar and Texts[6] in 1925.

In 1923, she took up a position as Instructor in Anthropology at Barnard College. In the same year, she began doing fieldwork on Navajo with Pliny Earle Goddard, and she returned to this work for several summers. After Goddard's death in 1928, Reichard spent her summers living in a Navajo household, learning to weave, tend sheep and participate in the daily life of a Navajo woman. Eventually she became a speaker of Navajo, an accomplishment that is connected to her major works on the language and culture.[7]

Her work on Coeur d'Alene was undertaken during visits to Tekoa, Washington, in 1927 and 1929. She worked with a small group of speakers, three of whom were members of the Nicodemus family – Dorthy Nicodemus, Julia Antelope Nicodemus, and Lawrence Nicodemus, who was Dorthy's grandson.[8] Julia was Reichard's primary translator and interpreter within the group, which also included master storyteller Tom Miyal.[9] Lawrence Nicodemus, who later came to Columbia University to work with Reichard,[8] went on to develop a practical writing system for Coeur d'Alene, and to publish a root dictionary, a reference grammar, and several textbooks on the language.[10][11][12][13]

She returned to work with Navajo during the middle 1930s and continued until the early 1950s. She started a Navajo school in which she worked with students to develop a practical orthography for the Navajo language.[8] Adee Dodge briefly worked as a Navajo language consultant to Reichard in the mid-1930s.[14] During the 1940s, she undertook a broader analysis of Navajo language, belief system, and religious practice which culminated in the two volume study, Navaho Religion, published in 1950 by the Bollingen Foundation.[15] An extensive collection of her notes on Navajo ethnology and language is held by the Museum of Northern Arizona.[16]

Reichard was made full professor at Barnard in 1951 and remained there until her death in 1955.[17] This was for many years the only Department of Anthropology at an undergraduate women's college, and a number of women anthropologists were trained by her.[5]

Reichard died in Flagstaff and is buried in the city's Citizens Cemetery.[18]

Conflicts with Sapir and colleagues

editAs documented by Julia Falk,[2][3] Reichard's work on Navajo in particular was the subject of conflict with other scholars at the time, particularly Edward Sapir and Harry Hoijer, and as a result has not been as often cited as theirs. The conflicts centered around Reichard's scholarly interests, her work style, and her status as a woman working in a linguistic territory claimed by men.

Reichard's scholarly interests centered around the interrelationships of language, culture, religion and art, and she was attentive to the role of language variation in her work. These interests put her at odds with the emerging Sapir school, which focused much more intently on issues of historical reconstruction of language groups, and on a particular approach to the structural analysis of language. Reichard was not interested in historical reconstruction, and expressed impatience with Sapir's attentiveness to the so-called 'phonemic principle'. Reichard's transcriptions were therefore virtually always narrow phonetic transcriptions, and they reflected individual differences in speaker pronunciations. Sapir, and later his student Hoijer, interpreted these irregularities as 'errors', and used them to undermine the credibility of Reichard's work. Sapir and his students were particularly committed to the analysis of sound systems of language based on Sapir's 'phonemic principle', but Reichard was skeptical of the value of that approach, and its increasing influence in the field.[3]

Reichard's work style was immersive, painstaking and detailed. In her work on Coeur d'Alene and Navajo in particular, she spent significant time working with speakers of the languages in their family homes – often collaborating with speakers in both language collection and linguistic analysis. Her co-author Adolph Bitanny[3] was a Navajo speaker who worked with Reichard in the Hogan School she established during her time in Navajo country.[3] She discusses the Hogan School approach in the fictionalized work Dezba, Woman of the Desert,[19] where she also reflects on the experiences Navajo speakers had with other educational institutions.

Honors and service

editReichard received a Guggenheim fellowship in 1926.[20] Over the course of her career, she served as secretary for the American Ethnological Society, the American Folk-Lore Society, the Linguistic Circle of New York, and the American Association for the Advancement of Science.[16][21]

Major works

editReichard published a variety of works relating to anthropology, linguistics, comparative religion and ethnography of art.

- 1925: Wiyot Grammar and Texts[6]

- 1928: Social Life of the Navajo Indians with Some Attention to Minor Ceremonies.[22]

- 1932: Melanesian Design (2 volumes)[23]

- 1932: Spider Woman: A Story of Navajo Weavers and Chanters[24]

- 1936: Navajo Shepherd and Weaver[25]

- 1938: "Coeur d'Alene", in Handbook of American Indian Languages[26]

- 1939: Dezba, Woman of the Desert[19]

- 1939: Navajo Medicine Man: Sandpaintings and Legends of Miguelito[27]

- 1939: Stemlist of the Coeur d'Alene Language[28]

- 1940: Agentive and Causative Elements in Navajo (co-authored with Adolph Bitanny)[29]

- 1944: The Story of the Navajo Hail Chant[30]

- 1945: Composition and Symbolism of the Coeur d'Alene Verb Stem[31]

- 1945: Linguistic Diversity Among the Navaho Indians.[32]

- 1947: An Analysis of Coeur d'Alene Indian Myths[9]

- 1948: Significance of Aspiration in Navaho[33]

- 1949: The Character of the Navaho Verb Stem[34]

- 1949: Language and Synesthesia (co-authored with Roman Jakobson and Elizabeth Werth)

- 1950: Navaho Religion: A Study of Symbolism (2 volumes)[35]

- 1951: Navaho Grammar[36]

- 1958–1960: A Comparison of Five Salish Languages (in 6 parts)[37]

References

edit- ^ "Reichard, Gladys (1893–1955)". Encyclopedia of Anthropology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Reference. 2006.

- ^ a b Falk, Julia S. (1999). History of Linguistics 1996. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. pp. 111–118. ISBN 978-1556192135.

- ^ a b c d e Falk, Julia S. (1999). Women, Language and Linguistics: Three American Stories from the First Half of the Twentieth Century. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415133159.

- ^ a b c Babcock, Barbara A.; Parezo, Nancy J. (1988). Daughters of the Desert: Women Anthropologists and the Native American Southwest, 1880–1980. University of New Mexico Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-0826310873.

- ^ a b Smith, Marian W. (1956). "Gladys Armanda Reichard" (PDF). American Anthropologist. 58 (5): 913–916. doi:10.1525/aa.1956.58.5.02a00100. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-05-09. Retrieved 2017-12-21.

- ^ a b Reichard, Gladys (1925). Wiyot Grammar and Texts. Vol. 22. University of California: University of California Press.

- ^ Lavender, Catherine (2006). Scientists and Storytellers: Feminist Anthropologists and the Construction of the American Southwest. University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 978-0826338686.

- ^ a b c "Texts". Coeur d'Alene Online Language Resource Center. 2009. Archived from the original on 9 February 2017. Retrieved 1 Dec 2016.

- ^ a b Reichard, Gladys (1947). An analysis of Coeur d'Alene Indian myths. with Adele Froelich. Philadelphia: American Folklore Society.

- ^ Nicodemus, Lawrence (1975). Snchitsu'umshtsn: The Coeur d'Alene language. Spokane, WA: Coeur d'Alene Tribe.

- ^ Nicodemus, Lawrence (1975). Snchitsu'umshtsn: The Coeur d'Alene language. A modern course. Spokane: WA: Coeur d'Alene Tribe.

- ^ Nicodemus, Lawrence; Matt, Wanda; Hess, Reva; Sobbing, Gary; Wagner, Jill Maria; Allen, Dianne (2000). Snchitsu'umshtsn: Coeur d'Alene reference book Volumes 1 and 2. Spokane: WA: Coeur d'Alene Tribe.

- ^ Nicodemus, Lawrence; Matt, Wanda; Hess, Reva; Sobbing, Gary; Wagner, Jill Maria; Allen, Dianne (2000). Snchitsu'umshtsn: Coeur d'Alene workbook I and II. Spokane: WA: Coeur d'Alene Tribe.

- ^ "Adee Dodge papers, 1930–2005". Connecticut's Archives Online, Western CT State University. Archived from the original on 2024-04-02. Retrieved 2024-04-02.

- ^ "Gladys Reichard – Anthropology". anthropology.iresearchnet.com. Archived from the original on 2018-08-25. Retrieved 2017-12-21.

- ^ a b "Gladys A. Reichard collection, 1883–1984". www.azarchivesonline.org. Archived from the original on 2017-12-22. Retrieved 2017-12-21.

- ^ "Gladys A. Reichard". barnard.edu – Barnard College. Archived from the original on 2018-05-27. Retrieved 2017-12-21.

- ^ "Gladys A. Reichard". arizonagravestones.org. Gravestone Photo Project (GPP).

- ^ a b Reichard, Gladys (1939). Dezba, Woman of the Desert. New York: J.J. Augustin.

- ^ Gladys Amanda Reichard Archived 2014-03-14 at the Wayback Machine - John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation

- ^ Women Anthropologists: Selected Biographies. University of Illinois Press. 1989. ISBN 978-0252060847.[page needed]

- ^ Reichard, Gladys (1928). Social Life of the Navajo Indians, with Some Attention to Minor Ceremonies. New York: Columbia University Press.

- ^ Reichard, Gladys (1932). Melanesian Design. New York: Columbia University Press.

- ^ Reichard, Gladys (1934). Spider Woman: A story of Navajo Weavers and Chanters. New York: Columbia University Press. Archived from the original on 2023-09-26. Retrieved 2024-04-02.

- ^ Reichard, Gladys (1936). Navajo Shepherd and Weaver. New York: J.J. Augustin.

- ^ Reichard, Gladys (1938). Boaz, Frans (ed.). Handbook of American Indian Languages: Coeur d'Alene. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 515–707.

- ^ Reichard, Gladys (1939). Navajo Medicine Man: Sandpaintings and Legends of Miguelito. New York: J.J. Augustin.

- ^ Reichard, Gladys (1939). "Stem – list of the Coeur d'Alene language". International Journal of American Linguistics. 10 (2/3): 92–108. doi:10.1086/463832. S2CID 145536775.

- ^ Reichard, Gladys; Bitanny, Adolph (1940). Agentive and Causative Elements in Navajo. New York: J.J. Augustin.

- ^ Reichard, Gladys (1944). The Story of the Navajo Hail Chant. New York: Barnard College, Columbia University.

- ^ Reichard, Gladys (1947). "Composition and symbolism of Coeur d'Alene Verb Stems". International Journal of American Linguistics. 11: 47–63. doi:10.1086/463851. S2CID 144928238.

- ^ Reichard, Gladys (1945). "Linguistic diversity among the Navaho Indians". International Journal of American Linguistics. 11 (3): 156–168. doi:10.1086/463866. S2CID 143774525.

- ^ Reichard, Gladys (1948). "Significance of aspiration in Navaho". International Journal of American Linguistics. 14: 15–19. doi:10.1086/463972. S2CID 144737470.

- ^ Reichard, Gladys (1948). "The character of the Navaho verb stem". Word. 5: 55–76. doi:10.1080/00437956.1949.11659352.

- ^ Reichard, Gladys (1950). Navaho Religion: A Study of Symbolism. Bollingen Series, 18. New York: Pantheon.

- ^ Reichard, Gladys (1951). Smith, Marian (ed.). Navaho Grammar. Publications of the American Ethnological Society. New York: J.J. Augustin.

- ^ Reichard, Gladys (1958–1960). "A comparison of five Salish languages. (Six parts)". International Journal of American Linguistics. 24–26: 8–15, 50–61, 90–96, 154–167, 239–253, 293–300. doi:10.1086/464478. S2CID 143819320.