Friendship Cemetery is a cemetery located in Columbus, Mississippi. In 1849, the cemetery was established on 5 acres by the Independent Order of Odd Fellows.[3] The original layout consisted of three interlocking circles, signifying the Odd Fellows emblem.[4] By 1957, Friendship Cemetery had increased in size to 35 acres, and was acquired by the City of Columbus. The cemetery was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1980 and was designated a Mississippi Landmark in 1989. As of 2015, the cemetery contained some 22,000 graves within an area of 70 acres and was still in use.[5] The Mississippi School for Mathematics and Science hosts a public event every April at night in the cemetery. Students complete a research project on someone buried at the cemetery, before dressing up and doing a performance as the person they researched.[6]

Friendship Cemetery | |

View within Friendship Cemetery | |

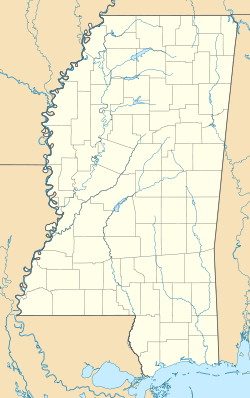

| Location | 1300 4th Street South, Columbus, Mississippi |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 33°28′51″N 88°25′50″W / 33.48083°N 88.43056°W |

| Area | 70 acres |

| Built | 1849 |

| NRHP reference No. | 80002287 |

| USMS No. | 087-CBS-1601-NR-ML |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | July 23, 1980[2] |

| Designated USMS | December 14, 1989[1] |

Memorial Day connection

editDuring the American Civil War, Columbus served as a military hospital center for the wounded, particularly after the Battle of Shiloh.[7] More than 2,000 Confederate soldiers were interred in Friendship Cemetery,[8] along with 40 to 150 Union soldiers.[9]: 127

In 1866, four women, who became known as the Decoration Day Ladies, organized a formal procession and ceremony to be held at Friendship Cemetery on April 26 so that a large group of Columbus women, both young and old, could place flowers atop the graves of these fallen Confederate and Union soldiers.[10] The women's tribute – treating the soldiers as equals – inspired poet Francis Miles Finch to write the poem, The Blue and the Gray, which was published in an 1867 edition of The Atlantic Monthly.[8][11] In 1867, the remains of all Union soldiers were exhumed and reinterred in Corinth National Cemetery.[3] Over time, these grave decoration days – honoring those who died in military service – eventually morphed into Memorial Day.[12]

Monuments

editThe cemetery contains two Confederate monuments:[3]

-

Monument to Confederate dead (1873)

-

Monument to an unknown Confederate soldier (1894)

Notable interments

edit- William Edwin Baldwin (1827–1864), Confederate brigadier general during the American Civil War.[8]

- William Barksdale (1821–1863), Confederate brigadier general during the American Civil War. Cenotaph only, Barksdale's remains were interred in Greenwood Cemetery (Jackson, Mississippi).[13]

- William S. Barry (1821–1868), member of the Provisional Congress of the Confederate States (1861–62).[3]

- William Cocke (1748–1828), U.S. Senator from Tennessee (1796–97, 1799–1805).[8]

- Cornell Franklin (1892–1959), judge who served as chairman of the Shanghai Municipal Council (1937–40).

- Jeptha Vining Harris (1816–1899), Confederate brigadier general during the American Civil War.[8]

- James Thomas Harrison (1811–1879), member of the Provisional Congress of the Confederate States (1861–62).[8]

- Clyde S. Kilby (1902–1986), noted American author and English professor.[8]

- Stephen Dill Lee (1833–1908), Confederate lieutenant general during the American Civil War.[8]

- Joshua Lawrence Meador (1911–1965), Disney animator.[14]

- Jehu Amaziah Orr (1828–1921), member of the Provisional Congress of the Confederate States and the Second Confederate Congress.[8]

- Jacob H. Sharp (1833–1907), Confederate brigadier general during the American Civil War.[8]

- Jesse Speight (1795–1847), U.S. Senator from Mississippi (1845–47).[8]

- Henry Edward Warden (1915–2007), Career officer in the US Air Force; father of the B-52.[15]

- Henry Lewis Whitfield (1868–1927), Governor of Mississippi (1924–27).[8]

- James Whitfield (1791–1875), Governor of Mississippi (1851–52).[8]

References

edit- ^ "Mississippi Landmarks (Lowndes County)". Mississippi Department of Archives and History. Retrieved 2018-01-02.

- ^ National Park Service, Digital Asset Management System (Friendship Cemetery) Retrieved 2018-01-02

- ^ a b c d "National Register of Historic Places Registration: Friendship Cemetery". National Park Service. April 28, 1980. Retrieved 2018-01-01. With 9 photos from 1980.

- ^ "Welcome to IOOF". www.ioof.org. Advanced Solutions International. Retrieved 2018-01-02.

- ^ "Historic Friendship Cemetery is still open for business". The Commercial Dispatch. Retrieved 2018-01-02.

- ^ McCollum, Anna. "Columbus students tell 'Tales from the Crypt'". Mississippi Today. Retrieved 2024-05-05.

- ^ "Lowndes County, Mississippi History". lowndes.msghn.org. Archived from the original on 2018-01-21. Retrieved 2018-01-02.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Brown, Alan (2016-09-26). Ghosts of Mississippi's Golden Triangle. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 9781439657591.

- ^ Lipscomb, William Lowndes (1909). A History of Columbus, Mississippi, During the 19th Century. Press of Dispatch printing Company.

- ^ "Image 191 of A history of Columbus, Mississippi, during the 19th century,". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved 2024-06-17.

- ^ Fallows, James. "A Famous Civil War Poem Comes to Life in Contemporary Mississippi". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2018-01-02.

- ^ "Memorial Day". www.usmemorialday.org. Retrieved 2018-01-02.

- ^ William Barksdale biography Archived 2013-09-16 at the Wayback Machine, Sons of Confederate Veterans.

- ^ Wilson, Sarah (October 18, 2009). "Son of Disney animator speaks on father's legacy". Dispatch. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- ^ Swopes, Bryan (2018-12-08). "8 December 1945". This Day in Aviation. Retrieved 2019-08-29.

External links

editMedia related to Friendship Cemetery (Columbus, Mississippi) at Wikimedia Commons