Paul Byrne (29 January 1959 – 13 September 2019[2][3]), who used the pseudonym Frank Key, was a British writer, illustrator, blogger and broadcaster[4][5] best known for his self-published short-story collections and his long-running radio series Hooting Yard on the Air, which was broadcast weekly on Resonance FM from April 2004 until 2019.[6] Key co-founded the Malice Aforethought Press with Max Décharné and published the fiction of Ellis Sharp. According to one critic, "Frank Key can probably lay claim to having written more nonsense than any other man living."[7]

Frank Key | |

|---|---|

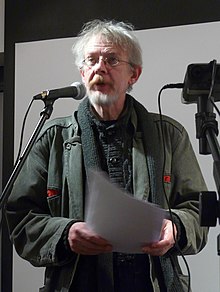

Key giving a reading in 2011 | |

| Born | Paul Byrne 29 January 1959 Barking, Essex, United Kingdom[1] |

| Died | 13 September 2019 (aged 60) London, United Kingdom |

| Occupation | Writer, broadcaster |

| Nationality | British |

| Education | University of East Anglia |

| Genre | short story, nonsense, satire |

| Website | |

| hootingyard | |

Life

editFrank Key was born Paul Byrne on 29 January 1959 in Barking, Essex.[8][9][1] His father Francis Byrne was a history teacher,[10] communist,[11] and Labour councillor;[12] his mother Lydia Brusseel was Belgian, a Flemish-speaker from Ghent, who had met her future husband when he was stationed in the city at the end of the Second World War.[13]

Key grew up on the Marks Gate council estate in Dagenham[14] "in a home where Catholic faith and Socialist politics were the twin pillars of a moral life".[15] He attended The Campion School, a Roman Catholic grammar school in Hornchurch[16][17] and went on to study Art History at the University of East Anglia.[18]

After university he returned to London, working as a human resources and welfare officer for the London Borough of Islington.[19][20]

But a period of heavy drinking disrupted his creative, professional and family life,[21] a decade he often referred to as his "wilderness years."[22][19] A revival came in 2003 with the launch of the Hooting Yard blog, and in the following year he began regular broadcasts on Resonance.fm, which ran until his death.

Key was divorced and had two sons.[23][24][25] In later years, he referred to a muse, Pansy Cradledew, who occasionally took part in Hooting Yard broadcasts.[26][27]

He died on 13 September 2019. In March 2020 a retrospective exhibition of his graphic work and writing, curated by Pansy Cradledew and crowd-funded by friends and fans, was held at the Menier Gallery in Southwark.[28]

Writing

editEarly writing

editKey began writing and drawing as a teenager, and his first attempt at publishing was to advertise photocopied stories for mail order in Vole, with very limited success.[21][29]

He continued writing and publishing at university and it was in this period that he adopted the pseudonym which was to attach to all his later work: Byrne and a group of fellow first-years at UEA decided that they needed pseudonyms for a "samizdat publication", and Byrne took the name "Frank Key" from an advert for a Nottingham builders' merchant.[30]

As well as stories, Key also wrote poems, drew cartoons, published film and TV reviews in student magazines, and created collaged postcards, which he sold on a weekly stall in Norwich.[28][31]

Malice Aforethought Press

editBy 1986 Key was living and working in London and, inspired by the postpunk DIY ethic, he joined with his university friend Max Décharné to found the Malice Aforethought Press. Over the next few years they published a large number of short-run pamphlets. Their first efforts, Stab Your Employer and Smooching With Istvan, were collaborations, each writer contributing a number of pieces to an anthology. Subsequently, they published separately and started to publish work by other writers, including Ginseng Fuchsia Lefleur, Ellis Sharp and John Bently. Key's most substantial Malice Aforethought publication was Twitching and Shattered, a collection of seventeen stories with illustrations.[32][33]

Malice Aforethought's pamphlets brought them contacts in the world of small press publishing, which led to the commissioning of pieces by Key for the ReR Quarterly, a combined LP and magazine. This in turn introduced the duo to Ed Baxter and the incipient Small Press Group, in which they then became active, helping at book fairs and contributing to the Small Press Yearbooks.[32] In the same period, Key contributed a piece to each volume of the Massacre: An Anthology of Anti-naturalistic Fiction series.[34]

The pamphlets were generally photocopied, initially by furtive weekend use of Key's office photocopier but later using commercial services. A few later publications, such as Twitching and Shattered, were paperbacks.[32][33] Print-runs were short, with as few as 25 copies and, as Sam Jordison remarked in 2007, "So rare are these books that very few have even seen them."[35] However, some of the stories were later republished on the Hooting Yard blog, and the site's archive has synopses of six of the early pamphlets.[36] A number Key's works from this period were later republished in print: Unspeakable Desolation Pouring Down From The Stars,[37] Obsequies For Lars Talc, Struck By Lightning[38] from 1994, and three early Massacre: Anthology pieces in We Were Puny, They Were Vapid.[39] Obsequies For Lars Talc, Struck By Lightning was reprinted in paperback in 2017, Key's last print publication.[38]

Hooting Yard

editIn the mid-1990s, with small presses giving way to the Internet for non-commercial publishing,[19] Key set up a web site to host his writings and drawings.[40] The site took its name, "Hooting Yard", from a snippet of verse that had appeared in the 1987 Malice Aforethought pamphlet Smooching With Istvan,[41] and was subsequently used for a series of illustrated hand-drawn "Hooting Yard Calendars".[42]

This first site was a static online repository for earlier work and not yet a blog with regular postings of new material.[43][44] On 14 December 2003, however, newly sober, Key relaunched Hooting Yard as a home for new writing.[43][21]

In its new incarnation "Hooting Yard" was no longer just the name of the site but an imagined territory with characters and locations shared between the individual pieces, even if there was little concern for consistency.[45] As a reviewer wrote, "His world is fully-formed and sits at a 45-degree angle to our own. It has its own geography (a lot of spinneys and marshes and wharves) and a cast of indelible characters."[46] The Dabbler refers to "the fully-formed parallel universe of Hooting Yard, with its forts and wharves, its strange cities and haunted zoos, its inexplicable violence and its cast of outrageous characters including intrepid explorer Tiny Enid, prolific pamphleteer Dobson, the hapless Blodgett and the terrifying Grunty Man."[47]

The stories from the web site were collected in six volumes published under the Hooting Yard imprint and available as paperbacks and eBooks via Lulu.[42]

In 2014, Key published By Aërostat to Hooting Yard - A Frank Key Reader, a selection of 147 previously published stories, with an introductory essay by Roland Clare, "the first major commentary on the Hooting Yard oeuvre."[47]

Other writings

editAlongside Hooting Yard, between August 2010 and February 2016 Key was a regular contributor to The Dabbler blog, with his weekly column "Key's Cupboard".[48]

In 2015 Constable published Mr Key's Shorter Potted Brief, Brief Lives, a "modern, updated version of John Aubrey’s Brief Lives... consist[ing] of a single, unadorned fact about each of my subjects."[49]

Broadcasting

editResonance FM

editInvited by Ed Baxter to contribute to Resonance FM, on 14 April 2004 Key began broadcasting a weekly half-hour show on the station. Entitled Hooting Yard on the Air, it was broadcast live from Resonance FM's South London studios and consisted almost entirely of Key narrating his own short stories and observations. To date, Hooting Yard is the longest continuously running series on Resonance FM.[50][51]

While some of the broadcasts drew on Key's published work for print, new material was written specifically for spoken performance.[19]

A highly-individual style of narration adds a significant dimension to Key’s verbal balletics.[21]

Key sounds like an affable old uncle, blathering on after a few too many drinks at the holidays, yet before you know it all the kids have gathered round to listen to him, and then the parents shut up and sit down too.[52]

Resonance broadcast a number of Hooting Yard special episodes. In December 2007 Key and the performance artist Germander Speedwell performed the whole of Jubilate Agno,[53] an epic devotional poem by Christopher Smart This was the first and only time that this poem has been performed in its entirety on live radio.[54] The entire performance was in excess of three hours.

Key appeared in Episode 3 of Resonance FM's Tunnel Vision,[55] a series recorded entirely in the sewers under London.

Podcasting

editKey narrated for all of the Escape Artists podcasts: Escape Pod, Pseudopod, and PodCastle. In addition his short stories Bubbles Surge from Froth,[56] Boiled Black Broth and Cornets,[57] and Far Far Away[58] were performed by Norm Sherman on the short-fiction series Drabblecast.

Critical reception

editThe Guardian's literature columnist Sam Jordison described Frank Key as one of the most prolific living writers of literary nonsense.[59] The Guardian's David Stubbs wrote that Frank's prose "reminds of Max Ernst engravings gone Bonzo Doo-Dah".[60] The SF critic David Langford wrote "Frank Key's lumbering machinery is like nothing since Ralph 124C 41+ and other pillars of SF's wooden age, only more decrepit. He may even conceivably be writing steampunk.".[33] In a review of Twitching and Shattered, John Bently concluded, "It isn’t surrealism, it isn’t satire, it’s just not like anything else."[61] Edmund Baxter, the director of programming for Resonance FM wrote "Frank Key is one of the most important writers in English today".[6]

Published works

editPamphlets

edit- Key, Frank; Décharné, Maxim (1986). Stab Your Employer!.

- ——; —— (1987). Smooching With Istvan.

- Key, Frank (1987). A Zest For Crumpled Things.

- —— (1987). "Forty Visits to the Worm Farm".

- —— (1987). Hoots of Destiny.

- —— (1987). Tales of Hoon.

- —— (1990). He Keeps His Gutta-Percha in a Gunny Sack.

- —— (1988). The Churn in the Muck.

- —— (1989). The Brink of Cramp.

- —— (1989). The Immense Duckpond Pamphlet. Malice Aforethought. ISBN 1-871197-26-0.

- —— (1989). Twitching and Shattered. Malice Aforethought. ISBN 1-871197-90-2.

- —— (1989). Volleyball, Tar & Shuddering.

- —— (1989). House of Turps. Malice Aforethought. ISBN 1-871197-40-6.

- —— (1990). Sidney The Bat Is Awarded The Order of Lenin. Malice Aforethought. ISBN 1-871197-70-8.

- —— (1990). Penitence And Farm Implements.

- Natal, Perry; Key, Frank (1990). Bring Me the Head of Derek the Dust-Particle!. Indelible Inc. ISBN 1-871427-13-4.

- Key, Frank (1991). Crop Circles : The Crunlop Experiment. Malice Aforethought. ISBN 1-871197-80-5.

- —— (1991). "Danny Blanchfowler: A Life In Football". Malice Aforethought.

- —— (1993). Testimony of a Tundist.

- —— (1994). Obsequies For Lars Talc, Struck By Lightning. Malice Aforethought. ISBN 1-871197-41-4.

Books

editHooting Yard

edit- Key, Frank (2006). Befuddled By Cormorants. Hooting Yard.

- —— (2007). Unspeakable Desolation Pouring Down From The Stars. Hooting Yard.

- —— (2008). Gravitas, Punctilio, Rectitude and Pippy Bags. Hooting Yard.

- —— (2009). We Were Puny, They Were Vapid. Hooting Yard.

- —— (2010). Impugned by a Peasant. Hooting Yard.

- —— (2011). Porpoises Rescue Dick Van Dyke. Hooting Yard Global Domination Enterprises.

- —— (2012). Brute Beauty And Valour And Act, Oh, Air, Pride, Plume, Here Buckle!. Hooting Yard.

- —— (2014). The Funny Mountain. Hooting Yard. ISBN 9781326099442.

- Clare, Roland, ed. (2014). By Aerostat to Hooting Yard - A Frank Key Reader. Dabbler Editions.

- Key, Frank (2017). Obsequies For Lars Talc, Struck By Lightning (Reprint ed.). Hooting Yard. ISBN 9780244946227.

Other works

edit- Beckett, James; Key, Frank; Bradley, Will (2013). Works of James Beckett with constant interjections. New York: Westreich Wagner. ISBN 9780615726281.

- Key, Frank (2015). Mr Key's shorter potted brief, brief lives. London: Constable. ISBN 9781472115232.

Contributions to anthologies

editThe RēR Quarterly and its successor unFILEd: The RēR Sourcebook

edit- "Some Ponds, A Hotel, The Hollyhocks", Volume 2 No 2, Autumn 1987

- "Some Lesser-Known Editions Of The Bible", Volume 2 No 3, 1988

- "Making The Most Of Your Allotment", Volume 2 No 4, 1989

- "Woodenberry And Crunlop" (a cartoon strip), Volume 3 No 1, 1990

- "The Administration Of Lighthouses" Volume 4 No 2 (Unfiled) 1991(?)

The Massacre Anthology (Indelible Inc)

edit- "Woodenberry And Crunlop", Massacre 1 (1990)

- "Gigantic Bolivian Architectural Diagrams",Massacre 2 (1991)

- "Accidental Deaths Of Twelve Cartographers, No 8", Massacre 3 (1992)

- "The Book Of Gnats", Massacre 4 (1993)

- "The Phlogiston Variations", Massacre 5 (1994)

References

edit- ^ a b Clare 2014, p. 28.

- ^ Key, Frank. "An Important Anniversary". Hooting Yard. Resonance FM. Retrieved 19 September 2019.

- ^ "Frank Key RIP". Resonance FM. Archived from the original on 20 September 2019. Retrieved 19 September 2019.

- ^ "Welcome to Hooting Yard: The Exhibition". Menier Gallery. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- ^ "Frank Key". The Dabbler. Retrieved 22 March 2012.

- ^ a b Edmund, Baxter. "Six Years of Hooting Yard". Archived from the original on 19 August 2014.

- ^ Jordison, Sam (15 November 2007). "I'm talking nonsense. In a good way". The Guardian.

- ^ Key, Frank (30 July 2010). "Anathema". Hooting Yard. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

I'll have you know I was born in Dagenham… in Barking Hospital, to be precise.

- ^ Mixcloud. "Clear Spot: Return To Hooting Yard – 29th January 2020". Mixcloud. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

the late Frank Key, whose 61st birthday would have been today.

- ^ Clare 2014, p. 23.

- ^ Clare 2014, p. 26.

- ^ Tull, Rita Byrne. "On My Bookshelf – Slant Manifesto". Dispatches From the Former New World. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ Byrne, Stephen. "Francis Gabriel Byrne". Stephen Byrne Family Tree. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ Tull, Rita Byrne. "The Dream of an English Garden". Dispatches From the Former New World. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- ^ Tull, Rita Byrne. "On My Bookshelf – Slant Manifesto". Dispatches From the Former New World. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- ^ Key, Frank (19 October 2012). "My Favourite Jesuit". The Dabbler.

- ^ Key, Frank. "Campion Day". Hooting Yard. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- ^ Key, Frank (25 March 2013). "Comment on The Wild Ginger Man". The Dabbler.

- ^ a b c d Clare 2013.

- ^ Key, Frank (7 October 2014). "A Note On Nomenclature". Hooting Yard. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

In the mid-1980s I worked as a drudge and minion in a local authority office in London

- ^ a b c d Clare 2014, p. 15.

- ^ Langford 2020.

- ^ Key, Frank (16 April 2012). "On The Malice Aforethought Press". Hooting Yard. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- ^ Key, Frank. "Art". Hooting Yard. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ Key, Frank. "Father Hopkins". Hooting Yard. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ Key 2007, p. iii. "This book wouldn't exist without my Muse, Pansy Cradledew"

- ^ Key, Frank (8 March 2018). "The Dulcet Tones Of Pansy Cradledew". Hooting Yard. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ a b Cradledew, Pansy (30 January 2020). "Welcome to Hooting Yard: The Exhibition". Hooting Yard.

- ^ Key, Frank (11 September 2012). "On Out Of Print Non-Pamphlets". Hooting Yard. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- ^ Clare 2014, p. 53.

- ^ Key, Frank (29 December 2016). "A Postcard From The Last Century". Hooting Yard. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

In 1982 I spent much of my time making postcards, which I sold for a pittance to eager punters from what would now be called a pop-up stall in Norwich

- ^ a b c Key, Frank (16 April 2012). "On The Malice Aforethought Press". Hooting Yard. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- ^ a b c Langford 1993.

- ^ Key, Frank. "Books". Hooting Yard. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- ^ Jordison 2007a.

- ^ Key, Frank (17 April 2012). "On Mail Order In The Twentieth Century". Hooting Yard. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- ^ Key 2007.

- ^ a b Key 2017.

- ^ Key 2009.

- ^ Kohn 1996.

- ^ Clare 2014, p. 1555. "Traitor Bill shut up shop in Hooting Yard / And drowned himself in booze."

- ^ a b Key, Frank. "Books". Hooting Yard. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- ^ a b Key, Frank (14 December 2009). "Now We Are Six". Hooting Yard. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

a jumble of pre-Wilderness Years odds and ends

- ^ Key, Frank (18 December 2008). "Birthday Bewolfenbuttlement". Hooting Yard. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- ^ Clare 2014, p. 18.

- ^ Brit (24 November 2010). "Review: Impugned by a Peasant by Frank Key". The Dabbler. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- ^ a b "By Aerostat to Hooting Yard - A Frank Key Reader". The Dabbler. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- ^ Brit (20 September 2019). "RIP Frank Key". The Dabbler. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- ^ "Mr Key's Shorter Potted Brief, Brief Lives". Little Brown Book Group. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- ^ "A Hooting Yard Anthology". Resonance. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- ^ Clare 2014, p. 14.

- ^ Alden, Winston (2017). "Frank Key's Hooting Yard and the Tradition of Grand English Nonsense". steemit. Retrieved 28 July 2020.

- ^ "Frank Key presents Jubilate Agno". Resonance FM. Archived from the original on 19 August 2014.

- ^ Jordison 2007b.

- ^ "Tunnel Vision Episode 3".

- ^ Sherman, Norm. "Drabblecast Trifecta X".

- ^ Sherman, Norm (11 March 2009). "Drabblecast Episode 106". Archived from the original on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ^ Sherman, Norm (19 November 2008). "Drabblecast Episode 90". Archived from the original on 19 November 2009. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ^ Jordison, Sam. "I'm talking nonsense. In a good way". The Guardian.

- ^ Stubbs, David (15 June 2006). "Sounds eccentric". The Guardian.

- ^ Bently, John (2003). "Twitching and Shattered". In Bodman, Sarah (ed.). Artist's Book Yearbook 2003-2005 (PDF). Bristol: Impact Press. p. 11. ISBN 0953607690.

Sources

edit- Clare, Roland (25 September 2013). "Towards an article on Frank Key" (PDF). The Spoonbill Generator. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- Clare, Roland (2014). "Introduction by Roland Clare: Prelude and Fugue – Key of Frank". In Clare, Roland (ed.). By Aërostat to Hooting Yard - A Frank Key Reader. Dabbler Editions.

- Gompertz, Will (28 March 2020). "Pure gold: Will Gompertz reviews the pick of your online picks". BBC News. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- Jordison, Sam (15 November 2007). "I'm talking nonsense. In a good way". The Guardian.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Jordison, Sam (27 December 2007). "For I will consider Jubilate Agno". The Guardian.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Kohn, Marek (29 September 1996). "Technofile". The Independent. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- Langford, David (1993). "Mysteries of Frank Key". The New York Review of SF.

- Langford, David (3 March 2020). "Key, Frank". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

External links

editArchives

edit- The Hooting Yard Archives 1992-2019 — every known text, some with links to the podcasts.

- Hooting Yard on the Air podcast archive

- Unofficial Hooting Yard Archive Index, including an index by category.

- Hooting Yard Archives: Frank Key's original monthly compilations, December 2006 to March 2017 (Internet Archive).

- Principia Dobsoniana, a compilation of Hooting Yard pieces about Dobson, created by the Hooting Yard Archivists.

Other

edit- Frank Key, "On The Malice Aforethought Press", a brief history.

- Key's Cupboard - Frank Key at The Dabbler.

- Recipe for Gruel, animation by Sharon Smith for a piece by Frank Key.

- Alasdair Dickson, Frank Key remembered (forever)