Floyd Perry Baker (November 16, 1820 – May 27, 1909) was an American lawyer, land speculator, politician, government official, farmer, blacksmith, teacher, and newspaper editor well known for his activities as an early resident and community leader in Kansas from the 1860s until 1904 when he moved to Buffalo, New York.[5]

Floyd Perry Baker | |

|---|---|

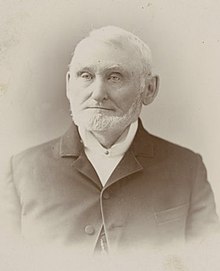

Baker circa 1875–1880[1] | |

| Born | November 16, 1820 |

| Died | May 27, 1909 (aged 88)[2] Topeka, Kansas, US |

| Resting place | Topeka Cemetery |

| Nationality | American |

| Other names | Fred Baker,[3] Father Baker |

| Occupation(s) | Newspaper editor & owner, lawyer government bureaucrat |

| Employer(s) | Self-employed, U.S. Government |

| Political party | Republican[4] |

| Spouse(s) | Eliza Wilson, Orinda Searle |

| Children | 6 |

Biography

editBaker was born at Fort Ann in Washington County, New York to Lois Comfort Chaffee Baxter, age 29, and Reuben Baker Jr., age 36. Because his father, Reuben, was a district school teacher[6] on a modest salary while supporting a wife and eleven children, Floyd was sent to live with a neighboring farmer Mathias Whitney from the age of eight until he was eighteen.[7]

Early years

editIn 1838, at the age of eighteen, Baker taught school for six months in Hamburg, New York. In the spring of 1839 he set up a blacksmith shop in Hillsdale, Michigan, located on Chicago Road.[7] He pursued that profession for one year then moved to Troy, New York, at which he owned an agency for packet boats on the Champlain Canal and a winter stage line between Albany and Whitehall, New York, a 72-mile route.[8] He operated these businesses for seven years.

On February 14, 1844, Baker married Eliza Folger Wilson in Amsterdam, New York. In 1847, Eliza gave birth to their son, Floyd Perry Baker Jr., in Troy, New York

About 1847, Baker entered into a contract to build two miles of the Hudson River Railroad near what was to become Irvington, New York. The venture bankrupted him.[9]

Wisconsin

editIn 1848, Baker relocated his family to Racine, Wisconsin where he studied law and was admitted to the bar. He also farmed and ran an insurance business. In the summer of 1849, while still living in Racine, Baker's wife, Eliza died. Nearly two years later, in the spring of 1851, Baker was remarried to Orinda Searle.[10] (Conflicting with this is the 1850 U.S. Census, taken on June 1, 1850, listing Floyd and Orinda Baker living in the same household.)[11]

In 1851, Albert Searle, the couple's first child was born. He died at the age of one in April 1852 in Racine.

While in Racine, Baker successfully ran for the positions of Justice of the Peace and Superintendent of Schools.[12]

After a 3-year stay in Wisconsin, he moved to San Francisco, California, at which he practiced law for 12 months until 1852.[13]

Move to Hawaii

editIn June 1853, Baker moved his family to the Sandwich Islands (Hawaii) where he was appointed as crown attorney and clerk of the district court of the islands. During the journey, which took the family down the Mississippi River, Floyd Perry Jr., Floyd's only child by his first wife, Eliza, died in New Orleans on January 5, 1853.[note 1] The trip took the Bakers from New Orleans to Aspinwall (Colon, Panama), the Atlantic-side terminus of the Panama isthmus railway, then to San Francisco and on the Sandwich Islands.[14] In August 1853, Floyd and Orinda's second son, Nestor Reuben, was born. On May 22, 1854, Floyd, residing in Hilo, was appointed by Register of Conveyances, Asher B. Bates and approved by the governor, George L. Kapeau, to the position of Agent for the Island of Hawaii.[15]

On October 14, 1854, a notice appeared in the newspaper, The Polynesian, announcing that Floyd Baker, Esq. had been replaced as District Attorney and Clerk of the Circuit Court for the District of Hilo by Richard R. Chamberlayne, Esq.[16]

One of his endeavors while in Hawaii was a real estate agency. On December 30, 1854, the newspaper Polynesian published an advertisement from Floyd promoting his law office in Honolulu at the corner of Beretania and Nuuanu Streets in which he solicited legal assistance to those having "houses, stores, farms, or other real estate for sale or rent, or money to loan..."[17]

On December 5, 1854, Baker appeared before the Chief Justice of the Hawaiian Islands Supreme Court in Honolulu to voluntarily declare bankruptcy.[18] In February, 1855, the Baker family left Hawaii, sailing first to San Francisco, then back to the central states via the Nicaragua route.[9]

Back to Wisconsin

editAfter returning to the U.S. from Hawaii, Floyd and his family resettled in Wisconsin where his fourth son (his and Orinda's third), Clifford Coan was born in May 1853.

Missouri

editThen, Floyd Baker moved his family to Andrew County, Missouri for several years where the couple's fourth son, Isaac Newcomb, was born in 1855.[note 2] With a history of moving his household to better living conditions, Floyd moved in about 1860 from pro-slavery Missouri, to free-state supportive Kansas. As a northerner, Baker found community relations difficult in pro-secession Missouri.[19]

Kansas Years

editAfter living in Missouri, he first settled in Centralia in Nemaha County, Kansas, shortly after the town was founded in 1859, then moved again to the capital city of Topeka in 1863 after investing in the Kansas State Record. While he was living in Centralia, Kansas entered the Union as the 34th state. On November 14, 1860, Baker was a delegate to the first meeting of the Territorial Relief Convention in Lawrence, Kansas. One of the purposes of the commission was to aid in the obtaining of relief loans from eastern capitalists to assist those citizens seeking funds for heavy farm mortgages, operating expenses or improvements.[20] While in Centralia, Floyd practiced law with a focus on debt collection and real estate transactions.[21] During this time he was also Nehmaha County Attorney and the Superintendent of Schools.

From 1861 to 1862 Baker was a member of the Kansas State Legislature. During the 1862 session, the legislature passed the first compilation of the laws of Kansas; the preparation of which was accomplished primarily by Floyd Baker and Wilson Davis.[22] During this election, Floyd Baker and a group of fellow Republicans ran as independents in opposition to other Republican candidates.[23]

In 1864, the Confederacy staged a military operation utilizing cavalry from Tennessee through Kentucky into Missouri in a campaign called Price's Raid. The Kansas militia was activated in response to this activity and on October 11, 1884, a F.P. Baker was mustered in as a private in Company A of the 2nd Regiment commanded by George W. Veal. His unit marched into Missouri and participated in the Battle of Byram's Ford.[24] Floyd Baker's service was short as the unit was only active for about 20 days. Furthermore, when he was mustered out later in October, he was listed as "absent without leave".

During the 1860s and 1870s Baker was heavily involved in his community. In 1862, while living in Nemaha County, he served as the temporary presiding officer during the formation of the Kansas State Agricultural Society, precursor of the Kansas Department of Agriculture, and later served as treasurer. Later he was a founding member of the Kansas Historical Society. In 1865 he was a founding member of the Sons of Temperance, Grand Division, State of Kansas.[25]

In 1868, Floyd was appointed to a three-year term as a trustee of the Kansas State Blind Asylum in Wyandotte, Kansas (now part of Kansas City, Kansas).[26] Starting in 1873 he was the editor-in-chief and publisher of the Topeka Commonwealth[27] (later absorbed by The Topeka Capital-Journal).

Texas

editFloyd relocated with his family (later reports state that just Floyd and one son moved for two years) to Denison, Texas, where he founded the Denison Journal.[note 3] On January 24, 1874, he was confirmed by the U.S. Senate as postmaster for that community.[28]

Back to Kansas

editReturning to Topeka, Baker was immediately involved in local affairs as a founding board member of the Kansas Historical Society on December 14, 1875.[29]

- Paris Universal Exhibition of 1878

- On February 10, 1878 Floyd Baker was appointed Additional Commissioner for the U.S. to the Paris Universal Exposition - 1878 by President Rutherford B. Hayes.[27][30]

- To fulfill that mission Floyd sailed from New York on April 18 (or possibly the 20th), 1878 arriving at the Exposition in Paris on May 1. The Exposition was incomplete so he took one month to travel to Italy. When he returned to Paris at the end of May, he commenced an assignment to write a report on the topic of forestry for the U.S. government. He remained in Paris until the middle of August then spent four weeks traveling western Europe visiting England, Scotland, the Netherlands and Belgium.[9][27][note 4]

Baker was a member of the Independent Order of Odd Fellows (IOOF). In 1872, he was elected in Topeka as Grand Patriarch of the Grand Encampment.[31]

Baker was appointed as chief of the Bureau of Forestry for the Mississippi valley west to the Rocky Mountains in 1882 by George B. Loring, U.S. Commissioner of Agriculture (precursor of the United States Forest Service) .[32] During the same year he was elected as president of the Kansas State Editorial Association.[33]

Move to Buffalo, New York

editIn 1904, Baker moved, along with his wife and his son Clifford C. to Buffalo. It is likely that the move was initiated by Clifford as he had sold his interest in the Topeka City Railway and joined a gentleman named Kinne as a partner in the coal business.[19]

Appointments and Offices

edit| Year | Organization | Title | Term |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1852 | Racine, Wisconsin | Justice of the Peace | - |

| 1852 | Racine, Wisconsin | Superintendent of Schools | - |

| 1853 | Kingdom of Hawaii | Crown Attorney | - |

| 1853 | Kingdom of Hawaii | Clerk - Hilo District Court | - |

| 1860 | Kansas Territorial Relief Commission | Delegate | - |

| 1860 | Public Instruction - Nemaha County, KS | Superintendent | 1860 |

| 1861 | Kansas counties of Nemaha, Marshall and Washington | State Representative | 1861 - ? |

| 1862 | Kansas State Agricultural Society | Presiding Officer | - |

| 1864 | 2nd Kansas Militia Infantry Regiment, Co. A | Private | 1864 |

| 1865 | Sons of Temperance, Grand Division, State of Kansas | Grand Worth Associate | 1865 |

| 1866 | Independent Order of Odd Fellows - Kansas | Grand Master | |

| 1868 | Kansas State Blind Asylum | Trustee | - |

| 1872 | Independent Order of Odd Fellows - Topeka Grand Encampment | Grand Patriarch | - |

| 1874 | U.S. Postal Service | Post Master-Dennison, TX | - |

| 1875 | Kansas Historical Society | Founding Board Member | - |

| 1878 | U.S. Delegation to the Paris International Exposition | Additional Commissioner | 1878 |

| 1882 | Kansas State Editors Association | President | - |

| 1882 | Brush Electric Light and Power Company - Topeka | President[34] | - |

| 1882 | U.S. Bureau of Forestry - Western States Division | Chief | - |

| 1891 | Parsons Water Supply Company | Director[35] | - |

| 1898 | U.S. Postal Service | Post Master-Station B-Topeka, KS[36] | 1898-1903 |

Notes

edit- ^ The circumstances of this trip are somewhat unclear as Floyd was in San Francisco for 12 months prior to it. Perhaps he was there by himself and he traveled back to Racine to pickup his family. A water trip via the Mississippi would have been a more practical way for his wife and son to get to San Francisco than an overland route.

- ^ This move placed Floyd and his family in close proximity to the border conflicts between abolitionists and pro-slavery supporters that led up to the U.S. Civil War.

- ^ Denison was founded in 1872 simultaneously with the Missouri-Kansas-Texas Railroad.

- ^ While traveling in Europe Floyd wrote about 50 letters to his newspaper, The Weekly Commonwealth, Topeka, Kansas. Many were published. One such letter from the May 30, 1878 edition describes a 29-hour train trip from Paris to Genova.

References

edit- ^ Baker, Floyd Perry. "Floyd Perry Baker cabinet card". www.kansasmemory.org. Kansas State Historical Society. Retrieved January 6, 2016.

- ^ "An Old Timer Dead". The Wyandotte Herald. Kansas City, Kansas. June 3, 1909. p. 1.

- ^ "The Daily Globe". The Atchison Daily Globe. Atchison, Kansas. August 28, 1883. p. 2.

- ^ "Politics and Politicians". The Emporia Weekly News. Emporia, Kansas. November 24, 1881. p. 2.

- ^ "Bakers to Leave". The Topeka State Journal. December 23, 1903. p. 1. Retrieved February 15, 2019.

- ^ The Chaffee Genealogy. New York, New York: The Grafton Press. 1909. pp. 371–372.

- ^ a b "The Wandering Ulysses of Kansas Journalism". The Weekly Commonwealth. Topeka, Kansas. October 28, 1886. p. 2.

- ^ Palmer, Richard (January 9, 2023). "Principal Stagecoach Routes in New York State in 1843". Allegany County Historical Society Local History and Genealogy. Retrieved January 9, 2023.

- ^ a b c The United States Biographical Dictionary, Kansas Volume. S. Lewis & Company. 1879. pp. 580–581. Retrieved January 8, 2016.

- ^ Wisconsin, State of. Wisconsin Vital Records Index (Volume 1 ed.). Wisconsin Department of Health and Family Services. p. 0158.

- ^ 1850 United States Federal Census, Year:1850;Census Place:Racine, Racine, Wisconsin;Roll:M432_1004;Page:80B;Image:162

- ^ "Town Ticket". Racine Advocate. Racine, Wisconsin. April 7, 1852. p. 2. Retrieved January 7, 2016.

- ^ King, James L. (1905). Shawnee County, Kansas and Representative Citizens. Chicago, Illinois: Richmond & Arnold. pp. 594–597.

- ^ "50th Anniversary". The Topeka Daily Capital. Topeka, Kansas. March 8, 1900. p. 3. Retrieved January 17, 2016.

- ^ "By Authority". Polynesian. Honolulu, Hawaii. June 3, 1854. p. 2. Retrieved January 7, 2016.

- ^ "Appointment". Polynesian. October 14, 1854. p. 2. Retrieved January 7, 2016.

- ^ "Parties in Honolulu". Polynesian. Honolulu, Hawaii. December 30, 1854. p. 3. Retrieved January 7, 2016.

- ^ "Notice of Bankruptcy". Polynesian. Honolulu, Hawaii. January 13, 1855. p. 3.

- ^ a b Baker, Floyd (December 23, 1903). "Bakers To Leave". The Topeka State Journal. p. 1. Retrieved January 28, 2020.

- ^ "Territorial Relief Convention". The Topeka Tribune. Topeka, Kansas. November 17, 1960. p. 2. Retrieved January 8, 2016.

- ^ "Advertisement - F.P. Baker, Attorney and Counsellor at Law". White Cloud Kansas Chief. White Cloud, Kansas. May 8, 1862. p. 3. Retrieved January 8, 2016.

- ^ "The Kansas Legislature". The Topeka Daily Capital. Topeka, Kansas. September 18, 1886. p. 5.

- ^ "An Old Flag". The Daily Commonwealth. May 19, 1982. p. 4. Retrieved January 18, 2016.

- ^ "Kansas State Muster Roles". www.kansasmemory.org. Kansas Adjutant General's Office. p. 55. Retrieved September 4, 2017.

- ^ "Grand Division of the Sons of Temperance". Lawrence, Kansas: The Daily Kansas Tribune. October 3, 1865. p. 4. Retrieved September 4, 2017.

- ^ Taylor, R.B. (May 2, 1868). "Editorial Section". Wyandotte Commercial Gazette. p. 2. Retrieved January 18, 2016.

- ^ a b c Miller, Char (2004), "French Lessons, F.P. Baker, American Forestry, and the 1878 Paris Universal Exposition" (PDF), Forestry History Today (Spring/Fall 2005): 10–15, ISBN 0-89030-062-3, archived from the original (PDF) on December 8, 2015, retrieved November 29, 2015

- ^ "Nominations Confirmed by the Senate". The New York Times. New York, New York. January 24, 1874. p. 1.

- ^ "List of Members". The Topeka Daily Capital. October 23, 1898. p. 16. Retrieved January 7, 2016.

- ^ "Washington - Commissioners to Paris". The Atchison Daily Champion. Atchison, Kansas. February 10, 1878. p. 1.

- ^ "Odd Fellows". Fort Scott Daily Monitor. Fort Scott, Kansas. October 10, 1972. p. 1. Retrieved January 9, 2016.

- ^ "Kind Words form the Brethern". The Weekly Commonwealth. Topeka, Kansas. August 17, 1882. p. 1. Retrieved January 18, 2016.

- ^ "The Free Press belongs to no "Editorial Association",." The Osage City Free Press. Osage City, Kansas. June 22, 1882. p. 4. Retrieved January 18, 2016.

- ^ "Mr. Baker and the Dam". Kansas Democrat. Topeka, Kansas. April 18, 1891. p. 2. Retrieved January 9, 2023.

- ^ "Topeka Men and Money". Phillipsburg Herald. Phillipsburg, Kansas. June 11, 1891. p. 2. Retrieved January 18, 2016.

- ^ "Father Baker Quits". The Hutchinson News. Hutchinson, Kansas. July 3, 1903. p. 7. Retrieved January 18, 2016.