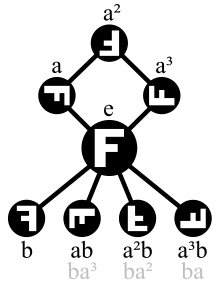

In algebra, a finitely generated group is a group G that has some finite generating set S so that every element of G can be written as the combination (under the group operation) of finitely many elements of S and of inverses of such elements.[1]

By definition, every finite group is finitely generated, since S can be taken to be G itself. Every infinite finitely generated group must be countable but countable groups need not be finitely generated. The additive group of rational numbers Q is an example of a countable group that is not finitely generated.

Examples

edit- Every quotient of a finitely generated group G is finitely generated; the quotient group is generated by the images of the generators of G under the canonical projection.

- A group that is generated by a single element is called cyclic. Every infinite cyclic group is isomorphic to the additive group of the integers Z.

- A locally cyclic group is a group in which every finitely generated subgroup is cyclic.

- The free group on a finite set is finitely generated by the elements of that set (§Examples).

- A fortiori, every finitely presented group (§Examples) is finitely generated.

Finitely generated abelian groups

editEvery abelian group can be seen as a module over the ring of integers Z, and in a finitely generated abelian group with generators x1, ..., xn, every group element x can be written as a linear combination of these generators,

- x = α1⋅x1 + α2⋅x2 + ... + αn⋅xn

with integers α1, ..., αn.

Subgroups of a finitely generated abelian group are themselves finitely generated.

The fundamental theorem of finitely generated abelian groups states that a finitely generated abelian group is the direct sum of a free abelian group of finite rank and a finite abelian group, each of which are unique up to isomorphism.

Subgroups

editA subgroup of a finitely generated group need not be finitely generated. The commutator subgroup of the free group on two generators is an example of a subgroup of a finitely generated group that is not finitely generated.

On the other hand, all subgroups of a finitely generated abelian group are finitely generated.

A subgroup of finite index in a finitely generated group is always finitely generated, and the Schreier index formula gives a bound on the number of generators required.[2]

In 1954, Albert G. Howson showed that the intersection of two finitely generated subgroups of a free group is again finitely generated. Furthermore, if and are the numbers of generators of the two finitely generated subgroups then their intersection is generated by at most generators.[3] This upper bound was then significantly improved by Hanna Neumann to ; see Hanna Neumann conjecture.

The lattice of subgroups of a group satisfies the ascending chain condition if and only if all subgroups of the group are finitely generated. A group such that all its subgroups are finitely generated is called Noetherian.

A group such that every finitely generated subgroup is finite is called locally finite. Every locally finite group is periodic, i.e., every element has finite order. Conversely, every periodic abelian group is locally finite.[4]

Applications

editThis section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (September 2017) |

Finitely generated groups arise in diverse mathematical and scientific contexts. A frequent way they do so is by the Švarc-Milnor lemma, or more generally thanks to an action through which a group inherits some finiteness property of a space. Geometric group theory studies the connections between algebraic properties of finitely generated groups and topological and geometric properties of spaces on which these groups act.

Differential geometry and topology

edit- Fundamental groups of compact manifolds are finitely generated. Their geometry coarsely reflects the possible geometries of the manifold: for instance, non-positively curved compact manifolds have CAT(0) fundamental groups, whereas uniformly positively-curved manifolds have finite fundamental group (see Myers' theorem).

- Mostow's rigidity theorem: for compact hyperbolic manifolds of dimension at least 3, an isomorphism between their fundamental groups extends to a Riemannian isometry.

- Mapping class groups of surfaces are also important finitely generated groups in low-dimensional topology.

Algebraic geometry and number theory

editCombinatorics, algorithmics and cryptography

edit- Infinite families of expander graphs can be constructed thanks to finitely generated groups with property T

- Algorithmic problems in combinatorial group theory

- Group-based cryptography attempts to make use of hard algorithmic problems related to group presentations in order to construct quantum-resilient cryptographic protocols

Analysis

editProbability theory

edit- Random walks on Cayley graphs of finitely generated groups provide approachable examples of random walks on graphs

- Percolation on Cayley graphs

Physics and chemistry

edit- Crystallographic groups

- Mapping class groups appear in topological quantum field theories

Biology

edit- Knot groups are used to study molecular knots

Related notions

editThe word problem for a finitely generated group is the decision problem of whether two words in the generators of the group represent the same element. The word problem for a given finitely generated group is solvable if and only if the group can be embedded in every algebraically closed group.

The rank of a group is often defined to be the smallest cardinality of a generating set for the group. By definition, the rank of a finitely generated group is finite.

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ Gregorac, Robert J. (1967). "A note on finitely generated groups". Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society. 18 (4): 756–758. doi:10.1090/S0002-9939-1967-0215904-3.

- ^ Rose (2012), p. 55.

- ^ Howson, Albert G. (1954). "On the intersection of finitely generated free groups". Journal of the London Mathematical Society. 29 (4): 428–434. doi:10.1112/jlms/s1-29.4.428. MR 0065557.

- ^ Rose (2012), p. 75.

References

edit- Rose, John S. (2012) [unabridged and unaltered republication of a work first published by the Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, England, in 1978]. A Course on Group Theory. Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-68194-8.