This article needs more reliable medical references for verification or relies too heavily on primary sources. (September 2019) |  |

Familial atrial fibrillation is an autosomal dominant heart condition that causes disruptions in the heart's normal rhythm.[1][2] This condition is characterized by uncoordinated electrical activity in the heart's upper chambers (the atria), which causes the heartbeat to become fast and irregular.

| Familial atrial fibrillation | |

|---|---|

| |

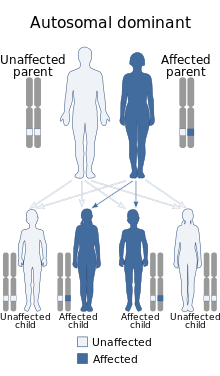

| Familial atrial fibrillation has an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance. | |

| Specialty | Medical genetics, cardiology |

Cause

editIt is associated with multiple genes:

| Type | OMIM | Gene | Locus |

|---|---|---|---|

| ATFB1 | 608583 | ? | 10q22-q24 |

| ATFB2 | 608988 | ? | 6q |

| ATFB3 | 607554 | KCNQ1 | 11 |

| ATFB4 | 611493 | KCNE2 | 21 |

| ATFB5 | 611494 | ? | 4q25 |

| ATFB6 | 612201 | NPPA | 1p36-p35 |

| ATFB7 | 612240 | KCNA5 | 12p13 |

| ATFB8 | 613055 | ? | 16q22 |

Mutations in the KCNQ1 gene cause familial atrial fibrillation. The KCNE2 and KCNJ2 genes are associated with familial atrial fibrillation. A small percentage of all cases of familial atrial fibrillation are associated with changes in the KCNE2, KCNJ2, and KCNQ1 genes. These genes provide instructions for making proteins that act as channels across the cell membrane. These channels transport positively charged potassium ions into and out of cells. In heart muscle, the ion channels produced from the KCNE2, KCNJ2, and KCNQ1 genes play critical roles in maintaining the heart's normal rhythm. Mutations in these genes have been identified in only a few families worldwide. These mutations increase the activity of the channels, which changes the flow of potassium ions between cells. This disruption in ion transport alters the way the heart beats, increasing the risk of syncope, stroke, and sudden death.[citation needed]

Most cases of atrial fibrillation are not caused by mutations in a single gene. This condition is often related to structural abnormalities of the heart or underlying heart disease. Additional risk factors for atrial fibrillation include high blood pressure (hypertension), diabetes mellitus, a previous stroke, or an accumulation of fatty deposits and scar-like tissue in the lining of the arteries (atherosclerosis). Although most cases of atrial fibrillation are not known to run in families, studies suggest that they may arise partly from genetic risk factors. Researchers are working to determine which genetic changes may influence the risk of atrial fibrillation.[citation needed]

Familial atrial fibrillation appears to be inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern, which means the defective gene is located on an autosome, and only one copy of the defective gene - inherited from one parent - is sufficient to cause the disorder.

Diagnosis

editIf untreated, this abnormal heart rhythm can lead to dizziness, chest pain, a sensation of fluttering or pounding in the chest (palpitations), shortness of breath, or fainting (syncope). Atrial fibrillation also increases the risk of stroke. Complications of familial atrial fibrillation can occur at any age, although some people with this heart condition never experience any health problems associated with the disorder. Atrial fibrillation is the most common type of sustained abnormal heart rhythm (arrhythmia), affecting more than 3 million people in the United States. The risk of developing this irregular heart rhythm increases with age. The incidence of the familial form of atrial fibrillation is unknown; however, recent studies suggest that up to 30 percent of all people with atrial fibrillation may have a history of the condition in their family.[citation needed]

Treatment

editThis section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (December 2017) |

References

edit- ^ Reference, Genetics Home. "Familial atrial fibrillation". Genetics Home Reference. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- ^ "Familial atrial fibrillation | Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program". rarediseases.info.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 20 January 2022. Retrieved 29 September 2019.