Eucalyptus marginata, commonly known as jarrah,[5] djarraly in Noongar language[6] and historically as Swan River mahogany,[7] is a plant in the myrtle family, Myrtaceae and is endemic to the south-west of Western Australia. It is a tree with rough, fibrous bark, leaves with a distinct midvein, white flowers and relatively large, more or less spherical fruit. Its hard, dense timber is insect resistant although the tree is susceptible to dieback. The timber has been utilised for cabinet-making, flooring and railway sleepers.

| Jarrah | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Myrtales |

| Family: | Myrtaceae |

| Genus: | Eucalyptus |

| Species: | E. marginata

|

| Binomial name | |

| Eucalyptus marginata | |

| Subspecies | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

Description

editJarrah is a tree which sometimes grows to a height of up to 50 m (160 ft) with a diameter at breast height (DBH) of 3.5 m (11 ft), but more usually 40 m (130 ft) with a DBH of up to 2 m (6 ft 7 in). Less commonly it can be a small mallee to 3 m (9.8 ft) high.[8] Older specimens have a lignotuber and roots that extend down as far as 40 m (100 ft). It is a stringybark with rough, greyish-brown, vertically grooved, fibrous bark which sheds in long flat strips. The leaves are arranged alternately along the branches, narrow lance-shaped, often curved, 8–13 cm (3–5 in) long and 1.5–3 cm (0.6–1 in) broad, shiny dark green above and paler below. There is a distinct midvein, spreading lateral veins and a marginal vein separated from the margin. The stalked flower buds are arranged in umbels of between 4 and 8, each bud with a narrow, conical cap 5–9 mm (0.2–0.4 in) long. The flowers 1–2 cm (0.4–0.8 in) in diameter, with many white stamens and bloom in spring and early summer. The fruit are spherical to barrel-shaped, and 9–20 mm (0.4–0.8 in) long and broad.[9][10][11][12][13]

Taxonomy and naming

editEucalyptus marginata was first formally described in 1802 by James Edward Smith, whose description was published in Transactions of the Linnean Society of London. Smith noted that his specimens had grown from seeds brought from Port Jackson and noted a resemblance to both Eucalyptus robusta and E. pilularis.[14][15] The specific epithet (marginata) is a Latin word meaning "furnished with a border".[16] Smith did not provide an etymology for the epithet but did note that, compared to E. robusta "the margin [of the leaves] is more thickened".[15]

Distribution and habitat

editEucalyptus marginata occurs in the south-west corner of Western Australia, generally where the rainfall isohyet exceeds 600 mm (20 in). It is found inland as far as Mooliabeenee, Clackline and Narrogin and in the south as far east as the Stirling Range. Its northern limit is Mount Peron near Jurien Bay but there are also outliers at Kulin and Tutanning in the Pingelly Shire. The plant often takes the form of a mallee in places like Mount Lesueur and in the Stirling Range but it is usually a tree and in southern forests sometimes reaches a height of 40 metres (130 ft). It typically grows in soils derived from ironstone and is generally found within its range, wherever ironstone is present.[9][17][18]

Ecology

editJarrah is regarded as one of the six forest giants found in Western Australia; the other trees include; Eucalyptus gomphocephala (tuart), Eucalyptus diversicolor (karri), Eucalyptus jacksonii (red tingle), Corymbia calophylla (marri) and Eucalyptus patens (yarri).[19][20]

Jarrah is an important element in its ecosystem, providing numerous habitats for animal life – especially birds and bees – while it is alive, and in the hollows that form as the heartwood decays. When it falls, it provides shelter to ground-dwellers such as the chuditch (Dasyurus geoffroii), a carnivorous marsupial.

Jarrah has shown considerable adaptation to different ecologic zones – as in the Swan Coastal Plain and further north, and also to a different habitat of the lateritic Darling Scarp.[21]

Jarrah is very vulnerable to dieback caused by the oomycete Phytophthora cinnamomi. In large sections of the Darling Scarp there have been various measures to reduce the spread of dieback by washing down vehicles, and restricting access to areas of forest not yet infected.

Conservation status

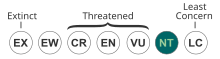

editEucalyptus marginata was added to the IUCN Red List as a "near threatened" species in 2019.[1]

Uses

editJarrah produces a dark, thick, tasty honey, but its wood is its main use. It is a heavy wood, with a specific gravity of 1.1 when green. Its long, straight trunks of richly coloured and beautifully grained termite-resistant timber make it valuable for cabinet making, flooring, panelling and outdoor furniture. The finished lumber has a deep rich reddish-brown colour and an attractive grain. When fresh, jarrah is quite workable but when seasoned it becomes so hard that conventional wood-working tools are near useless on it.[22] It is mainly used for cabinet making and furniture although in the past it was used in general construction, railway sleepers and piles. In the 19th century, famous roads in other countries were paved with jarrah blocks covered with asphalt.[5][9]

Jarrah wood is very similar to that of Karri, Eucalyptus diversicolor. Both trees are found in the southwest of Australia, and the two woods are frequently confused. They can be distinguished by cutting an unweathered splinter and burning it: karri burns completely to a white ash, whereas jarrah forms charcoal. This property of jarrah was critical to charcoal making and charcoal iron smelting operations at Wundowie from 1948 to 1981.[23] Most of the best jarrah has been logged in southwestern Australia.[citation needed]

A large amount was exported to the United Kingdom, where it was cut into blocks and covered with asphalt for roads. One of the large exporters in the late nineteenth century was M. C. Davies who had mills in the Augusta - Margaret River region of the southwest, and ports at Hamelin Bay and Flinders Bay.

The local poet Dryblower Murphy wrote a poem, "Comeanavajarrah" that was published in The Sunday Times of May 1904, about the potential to extract alcohol from jarrah timber.[24]

As of the banning of native logging in Western Australia in 2024,[25] jarrah has become more highly prized, and can only be obtained as recycled timber from sources such as demolished houses and railway sleepers.

Jarrah is used in musical instrument making, for percussion instruments and guitar inlays.

Because of its remarkable resistance to rot, jarrah is used to make hot tubs.

Eucalyptus marginata have been used for traditional purposes as well. Some parts of the jarrah tree were used as a remedy for some illnesses and diseases. Fever, colds, headaches, skin diseases and snakes bites were traditionally cured through the use of jarrah leaves and bark.[26]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b Fensham, R.; Laffineur, B.; Collingwood, T. (2019). "Eucalyptus marginata". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019: e.T61913695A61913703. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-3.RLTS.T61913695A61913703.en. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ a b "Eucalyptus marginata". Australian Plant Census. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ^ "Eucalyptus marginata subsp. marginata". Australian Plant Census. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ^ "Eucalyptus marginatasubsp. thalassica". Australian Plant Census. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ^ a b "Jarrah - Eucalyptus marginata". Forest Products Commission - Western Australia. Archived from the original on 26 June 2019. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- ^ "Noongar word list". Kaartdijin Noongar. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- ^ Hewett, Peter Neil. "Information sheet - "Tall Trees"" (PDF). Forests Department Western Australia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 September 2018. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- ^ Nicolle, Dean (2019). Eucalypts of Western Australia - The South-West Coast and Ranges (1st ed.). WA: Scott print. pp. 274–5. ISBN 978-0-646-80613-6.

- ^ a b c Gardner, Charles Austin (1987). Eucalypts of Western Australia. Perth: Western Australian Herbarium, Dept. of Agriculture, Western Australia. pp. 8–10. ISBN 0724489983.

- ^ Wrigley, John (2012). Eucalypts: A Celebration. Crows Nest, N.S.W.: Allen & Unwin. p. 60. ISBN 978-1-74331-080-9.

- ^ Lintern, Melvyn; Anand, Ravi; Ryan, Chris; Paterson, David (2013). "Natural gold particles in Eucalyptus leaves and their relevance to exploration for buried gold deposits". Nature Communications. 4: 2614. Bibcode:2013NatCo...4.2274L. doi:10.1038/ncomms3614. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 3826622. PMID 24149278.

- ^ "Eucalyptus marginata subsp. marginata". Centre for Australian National Biodiversity Research. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- ^ Boland, Douglas J.; Brooker, Ian; McDonald, Maurice W. (2006). Forest trees of Australia (5th ed.). Collingwood, Victoria: CSIRO Pub. p. 520. ISBN 0643069690.

- ^ "Eucalyptus marginata". APNI. Retrieved 26 September 2016.

- ^ a b Smith, James Edward (1802). "Botanical characters of four New-Holland plants, of the natural order of Myrti". Transactions of the Linnean Society of London. 6: 302. Retrieved 26 September 2016.

- ^ Brown, Roland Wilbur (1956). The Composition of Scientific Words. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press. p. 157.

- ^ Brooker, Ian (2012). Eucalyptus: An illustrated guide to identification. Chatswood, N.S.W.: Reed New Holland. p. 214. ISBN 978-1-921517-22-8.

- ^ Barrett, Russell (2016). Perth Plants. Clayton South, VIC: CSIRO Publishing. p. 124. ISBN 978-1-4863-0602-2.

- ^ "Eucalyptus gomphocephala". Australian Seed. Retrieved 22 August 2017.

- ^ "Eucalyptus gomphocephala". Plants For A Future. Retrieved 28 April 2023.

- ^ Powell, Robert James and Emberson, Jane (1978).An old look at trees : vegetation of south-western Australia in old photographs Perth : Campaign to Save Native Forests (W.A.). ISBN 0-9597449-3-2 – has photographs of significant large old jarrah trees from the Swan Coastal Plain in the late 19th and early 20th centuries

- ^ "Jarrah Timber. (Eucalyptus marginata, Sm.)". Bulletin of Miscellaneous Information (Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew). 1890 (45): 188–190. 1 January 1890. doi:10.2307/4118419. JSTOR 4118419.

- ^ Relix & Fiona Bush Heritage and Archaeology. "WUNDOWIE GARDEN TOWN CONSERVATION PLAN" (PDF). Wundowie Progress Association.

- ^ Murphy, Edwin G. "Comeanavajarrah". The Sunday Times (Western Australia). Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- ^ Lynch, Jacqueline; Forrester, Kate (1 January 2024). "Will there still be firewood? How Western Australia's native logging ban could affect you". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 7 January 2024.

- ^ Barrett, Russell (2016). Perth Plants. Clayton South, VIC: CSIRO Publishing. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-4863-0602-2.

Further reading

edit- Powell, Robert (1990). Leaf and Branch: Trees and Tall Shrubs of Perth. Department of Conservation and Land Management, Perth, Western Australia. ISBN 0-7309-3916-2..

- Wrigley, John W. & Fagg, Murray. (2012). Eucalypts: a celebration. Crows Nest, N.S.W: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-74331-080-9

External links

edit- "Eucalyptus marginata". FloraBase. Western Australian Government Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions.