Eubotas of Cyrene was a two-time Olympic champion from the city of Cyrene.

Stadion runners

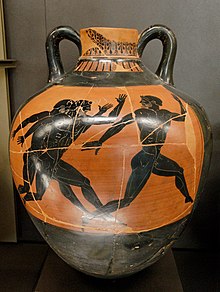

Panathenaic black-figure amphora, circa 500 B.C. Painter of Cleophrades (Louvre G65). | |

| Personal information | |

|---|---|

| Born | Cyrene |

| Sport | |

| Sport | Athletics |

| Event | |

As predicted by an oracle, Eubotas made history by winning the stadion (running race) at the 93rd Olympic Games in 408 BC. This victory marked the beginning of his legendary career in one of the most prestigious Games events. Forty-four years later, in 364 BC, at the 104th Games, he was awarded a second Olympic crown as owner of a carriage for the four-horse chariot race, the quadriga.

Biography

editVictory at the Olympic Games in 408

editAs Eubotas of Cyrene prepared for the stadion (about 192m) at the 93rd Olympic Games in 408, the oracle of Libya announced that he would win the event. In anticipation of this outcome, the athlete commissioned a statue to commemorate his victory.[1][2][3]

Eubotas' life took an unexpected turn in the months before the Games when he met a Corinthian hetairia named Laïs. She expressed a strong romantic interest in him and proposed marriage. Eubotas agreed to marry her but explained that he needed to focus on his Olympic preparations. He also declined her offer of services for the same reason.[1][4][5][6]

His victory in the stadion at the 93rd Olympic Games[1][7][8][9][10] was not just a typical win. It was a unique triumph, made even more impressive by the oracle's prophecy. Thanks to the oracle, he was among the few athletes to receive the olive wreath of victory and dedicate his statue[1][2][3] on the same day.

However, following his victory at the stadion, Eubotas was obliged to honor his oath to Laïs. At this juncture, he commissioned a life-size portrait of the young woman. By transporting the portrait to Cyrene, he demonstrated that he had fulfilled his oath.[1][4][5][6] In playing with the polysemy of the verb "to bring", which could mean "to marry"[5][Notes 1] or "to draw", Eubotas was able to create a subtle but effective narrative device. Some years later, his lawful wife commissioned a statue of Eubotas in Cyrene, celebrating his ability to resist temptation.[1][4]

Victory at the Olympic Games in 364

editThe τέθριππον / tethrippon, approximately 14 km long, was one of the oldest events at the ancient Olympic Games,[Notes 2][11] dating back to 680 BC. It was one of the most prestigious events and, above all, one of the most expensive. For this reason, the name of the carriage owner[12] was kept, not that of the auriga (charioteer). At the 104th Games in 364 BC, Eubotas of Cyrene was crowned a second time in Olympia, forty-four years after his first victory, as the owner of the winning carriage.[1][2][13]

However, the city of Elis, which had organized the Games, did not recognize the 104th Games. Indeed, in 364 BC, the Games were controlled by Pisa, a neighboring city allied with the Arcadians. Upon regaining control of the sanctuary, the Eleans declined to recognize the victories of the 104th Games, citing the unqualified status[1][2][3] of the Arcadian referees.

Other possible victories

editEpigram 86 from the Milan papyrus, generally attributed to Posidippus of Pella (2nd century BC), mentions a horse owner named Eubotas, who offers high praise for his horse, Aithon. Aithon won four races at the Nemean Games and two at the Pythian Games. This horse owner is often referred to as Eubotas of Cyrene. These six victories would, therefore, be added to his list of achievements.[14]

Hypothesis about another commemorative statue

editIn 2000, the Italian archaeological mission unearthed a badly damaged marble head while excavating at the sanctuary of Demeter in Cyrene. The head, measuring 9.5 cm in height, is believed to have represented a mortal. Through various details, the head is linked to Lysippus' "Hagias", a copy preserved in Delphi. The "Hagias", which celebrated a victorious pancratist at numerous Panhellenic games, was dedicated in Pharsalus for the original and in Delphi for the copy by the athlete's son, Daochos. This was done in honor of his father's victories.[15][16] Oscar Mei suggests that it is possible to conjecture that this Cyrenaic copy of Lysippus' "Hagias" may have been dedicated by Eubotas' son towards the end of the fourth century BC in honor of his father.[15]

See also

editNotes

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h Golden (2004, p. 63)

- ^ a b c d Pausanias (1796)

- ^ a b c Matz (1991, p. 55)

- ^ a b c Élien (1827)

- ^ a b c Sommerstein & Torrance (2014, pp. 266–267)

- ^ a b Golden (1998, p. 75)

- ^ Xénophon (1859)

- ^ Matz (1991, pp. 55, 123)

- ^ Diodore de Sicile (1851)

- ^ Eusèbe de Césarée (321, pp. 70–82)

- ^ Golden (1998, p. 169)

- ^ Matz (1991, p. 54)

- ^ Matz (1991, pp. 54–55)

- ^ Canali de Rossi (2011, pp. 50–51)

- ^ a b Luni (2010, pp. 117–120)

- ^ Homolle, Théophile (1897). "Statues du Thessalien Daochos et de sa famille". Bulletin de Correspondance Hellénique. 21 (1): 592–598. doi:10.3406/bch.1897.3566.

Bibliography

edit- Diodore de Sicile (1851). Bibliothèque historique (in French). Translated by Ferd Hoefer. Paris: ADOLPHE DELAHAYS.

- Élien (1827). Histoires variées (in French). Translated by Dacier. Paris: Imprimerie d'Auguste Delalain.

- Eusèbe de Césarée (321). Chronique (in French). Translated.

- Pausanias (1796). Description de la Grèce (in French). Translated by Nicolas Gedoyn. Paris: Debarle.

- Xénophon (1859). Helléniques (in French). Translated by EUGÈNE TALBOT. Paris.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Sommerstein, Alan H.; Torrance, Isabelle C.; et al. (Andrew J. Bayliss) (2014). ""Artful dodging", or the sidestepping of oaths". Oaths and Swearing in Ancient Greece. De Gruyter. ISBN 9783110200591.

- Canali de Rossi, Filippo (2011). Hippika : Corse di Cavalli e di Carri in Grecia, Etruria e Roma. Le radici classiche della moderna competizione sportiva (in Italian). Hildesheim: Weidmann. ISBN 9783615003840.

- Christesen, Paul (2007). Olympic Victor Lists and Ancient Greek History. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511550966. ISBN 9780511550966.

- Golden, Mark (1998). Sport and Society in Ancient Greece (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521497909.

- Golden, Mark (2004). Sport in the Ancient World from A to Z. Routledge. ISBN 9780415486729.

- Matz, David (1991). Greek and Roman Sport : A Dictionnary of Athletes and Events from the Eighth Century B. C. to the Third Century A. D. McFarland & Co Inc. ISBN 978-0899505589.

- Luni, Mario; et al. (Oscar Mei) (2010). "Una replica dell'Agia nel Santuario di Demetra a Cirene". Cirene nell'antichità (PDF) (in Italian). "L'Erma" di Bretschneider. p. 117.

- Moretti, Luigi (1957). Olympionikai, i vincitori negli antichi agoni olimpici (in Italian). Roma: Atti della Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei. pp. 55–199.

- Smith, William (1867). "Eubotas". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. Vol. 2. Little, Brown and co.

- Smith, William (1867). "Laïs". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. Vol. 2. Little, Brown and co.