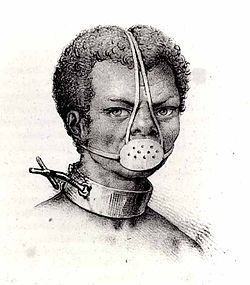

Escrava Anastacia (12 May 1740 – unknown) is a popular folk saint venerated in Brazil. An enslaved woman of African descent, Anastácia is depicted as possessing incredible beauty, having piercing blue eyes and wearing a punitive iron facemask. Although not officially recognized by the Catholic Church, Anastacia is an important figure in popular Catholic devotion throughout Brazil. She is also venerated by members of the Umbanda and Kardecist traditions. She has been portrayed in Brazil in books, radio programs, and a highly successful television miniseries bearing her name.[1]

Escrava Anastacia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 12 May 1740? |

| Venerated in | Folk Catholicism, Brazilian Catholic Church, Umbanda and Kardecismo |

| Attributes | African woman, blue eyes, facemask |

History of the Saint

editWithout an official history, stories of Anastacia's life vary. Some place her birth in Africa, where it is stipulated that Anastacia was the child of a black, female slave from the west coast of Africa. Her mother was raped by her enslaver, and Anastacia was the result — the first black child to be born with blue eyes. The plantation owner had the baby sent away, to hide the evidence of his ‘infidelity’ from his wife.

Others, on the other hand, emphasize her Brazilian origins where she was born in Africa, a Royal Princess who was enslaved and shipped to Brazil.[2][3] According to Carlos de Lima, a Brazilian historian, the enslaved Princess became a housekeeper on a sugar cane plantation. In all versions she is enslaved and cruelly treated by her enslavers. Anastacia stoically bears these traumas and treats all people with love. She is often purported to have possessed tremendous healing powers and to have performed other miracles. Eventually, she is punished by her owners by being forced to wear a muzzle-like facemask, which prevents her from speaking, and a heavy iron collar. The reasons given for this punishment vary: some stories report her aiding in the escape of other slaves, others claim she resisted rape by her master, and yet another places the blame on a mistress jealous of Anastacia's beauty. After a prolonged period of suffering, all the while performing more miracles of healing and peace, Anastacia dies of tetanus from the collar. It is often claimed that she healed the son of her master and mistress, and forgave their cruelty as she died.[citation needed]

History of veneration

editWhile there are reports of black Brazilians venerating an image of a slave woman wearing a facemask throughout the late 19th and early 20th century, the first wide-scale veneration of the Saint began in 1968 when the curators of the Museum of the Negro, located in the annex of the Church of Our Lady of the Rosary of Black Men and Saint Benedict in Rio de Janeiro erected an exhibition to honor the 80th anniversary of the Lei Áurea abolishing of slavery in Brazil. Among the displays was an engraving of a female slave wearing a punishment facemask. The image soon became the object of popular devotion and members of the Brotherhood of Black Men began collecting Anastacia stories in the early 1970s.[citation needed]

In the 1980s, the cult of Anastacia expanded from her original, poor, black base to include many progressive, middle-class whites. In 1984, an effort funded by the oil company Petrobras to officially canonize Anastacia brought her considerable attention. Seen as a symbol of racial harmony, her popularity expanded rapidly, especially among nurses, black women and prisoners. There were radio dramatizations of her life and on television, a popular miniseries and investigative reports were produced. She was also integrated into the Umbanda faith as one of the pretos velhos "old black slaves".[citation needed]

Present day

editLike other saints, devotion to Anastacia is a deeply personal experience amongst those who venerate her. The primary arena of this devotion is the use of small images—like prayer cards, medallions, statuettes, candles, etc.--through which the devotee prays for Anastacia to intercede on her behalf. Many also say prayers to Anastacia in times of difficulty or crisis. Often, devotees respond to intercessions by pilgrimage to one of several popular shrines. Here small offerings like flowers, jewelry, prayer cards and medallions are given to the image of the Saint.

Controversies

editIn May of 2020, during a demonstration in Humboldt County, California protesting social distancing and mask wearing, one protestor held up a sign showing a picture of Anastacia reading “Muzzles are for dogs and slaves. I am a human being.” The woman holding the sign claimed to not know the significance of the image, while historians and others identified it as Anastacia.[4] Some took offense as the sign seemingly both condoned slavery and compared an at-the-time 2-month-old lockdown to the centuries old system of oppression. Others wished to have Anastacia’s name be more well known, as this usage of her image demonstrated how unknown she was to the wider world.[5]

Cultural Legacy

Anastacia has been used by multiple social movements to symbolize many different causes. Her image was used in 1988 in a march against racism, it is used by millions of Brazilian women daily in the form of medallions, pictures, and prayer cards to advocate for women’s rights, and her image is used to symbolize liberation and rebellion.[6] Despite her existence being contested, Anastacia is used by many today as a symbol of inspiration and hope.[7]

In Popular Culture

editIn 1990, a mini-series entitled "Escrava Anastacia" was produced for Brazilian television. Directed by Henrique Martins, written by Paulo César Coutinho and starring Ângela Correa, it portrayed Anastacia as a Nigerian princess captured by slavers. Anastacia is sold to a cruel master who falls in love with her and eventually tries to rape her. For refusing her master, Anastacia is punished by being forced to wear a face mask.[8] The image of Anastacia healing the son of her oppressors is an innovation developed for this program.

Free Anastacia - Monument to Anastacia's voice

editGiven the contemporary use of Anastacia’s image by Black movements, representing the struggle of all under enslavement during colonial times and resistance against racism afterward, it is surprising that the suggestion of portraying her as a free woman was only applied in 2019 by the Brazilian artist Yhuri Cruz. Cruz is a political scientist and social journalist with personal ties to the Afro-Brazilian religion Umbanda, which also prays to Anastacia. His intervention reimagines the original image by the French artist Jacques Arago, removing the torture device from Anastacia’s mouth and revealing a “secret-smile”, a reference to the portrait of the Sudanese saint Josefina Bakhita (1869-1947). The frame shows camellias, a symbol of abolitionist actions, beneath it the image reads “Free Anastacia”. The image was widely exposed in Rio de Janeiro in the form of holy or prayer cards, a Christian tradition of small, devotional pictures for the use of the faithful that usually depict a religious scene or a saint in an image about the size of a playing card. The reverse typically contains a prayer, which was the case of “Free Anastacia”, the prayer to free Anastacia reminds her violent past but praises her freedom today by God. Yhuri Cruz named the intervention “Monument to Anastacia's voice”.[9]

References

edit- ^ "Escrava Anastácia | Rede Manchete" (in Brazilian Portuguese). Retrieved 2025-02-12.

- ^ Hayes, Kelly; Handler, Jerome (2009-01-01). "Escrava Anastácia: The Iconographic History of a Brazilian Popular Saint". African Diaspora. 2 (1): 25–51. doi:10.1163/187254609X430768. ISSN 1872-5457.

- ^ "Blessed Anastacia : Women, Race and Popular Christianity in Brazil". Taylor & Francis. 2013-01-11. doi:10.4324/9780203610541/blessed-anastacia-john-burdick. Archived from the original on 2022-06-23.

- ^ Hertzman, Marc; Xavier, Giovana (2020-07-30). "Let's Build a Monument to Anastácia". Public Seminar. Retrieved 2025-02-12.

- ^ Member, Daniel Villarreal NW-Writer Newsweek Is A. Trust Project (2020-05-21). "Woman Apologizes for Lockdown Protest Sign Comparing Face Masks to Slavery". Newsweek. Retrieved 2025-02-12.

- ^ November 28th; Lauro, 2022 Sarah Juliet. "Anastácia Diptych". Monument Lab. Retrieved 2025-02-12.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Maxwell, Kenneth (1999). "Review of Blessed Anastácia: Women, Race, and Christianity in Brazil". Foreign Affairs. 78 (3): 144–145. doi:10.2307/20049322. ISSN 0015-7120.

- ^ Burdick, John (1998). Blessed Anastácia: Women, Race, and Popular Christianity in Brazil. Routledge. pp. 75–76. ISBN 978-0415912600.

- ^ Pereira, Edilson (2023-11-27). "Da escravidão à liberdade: a imagem de Anastácia entre arte contemporânea, política e religião". Horizontes Antropológicos (in Portuguese). 29: e670410. doi:10.1590/1806-9983e670410. ISSN 0104-7183.

Sources

edit- BURDICK, John (1998): Blessed Anastacia: Women, Race, and Popular Christianity in Brazil, New York, Routledge. ISBN 0-415-91260-1

- Escrava Anastacia (mini-series, 1990) at the Internet Movie Database