The Erie Plain is a lacustrine plain that borders Lake Erie in North America. From Buffalo, New York, to Cleveland, Ohio, it is quite narrow (at best only a few miles/kilometers wide), but broadens considerably from Cleveland around Lake Erie to Southern Ontario, where it forms most of the Ontario peninsula. The Erie Plain was used in the United States as a natural gateway to the North American interior, and in both the United States and Canada the plain is heavily populated and provides very fertile agricultural land.

Creation of the plain

editThe Erie Plain is a lacustrine plain[1] consisting largely of sediment laid down by a series of proglacial lakes.[2] These existed in the late Pleistocene Epoch, about 25,000 years ago to about 11,700 years ago, and were created by glaciers of the Wisconsin glaciation (the last ice age).[3] The largest of these was Lake Whittlesey. In some places in Pennsylvania and Ohio, the Erie Plain is broken by the very slight former shoreline of Lake Warren.[4] This glacial sediment was laid atop the Chagrin and the Cleveland shales created in the late Devonian Period (382.5 to 359 million years ago),[5] as well as early Carboniferous Period shale in and west of Cleveland (laid down 359 to 346 million years ago).[6] West of Sandusky, Ohio, these sediments lie atop limestone laid down in the Silurian and Devonian periods.[7]

Due to its lacustrine origin, much of the soil of the Erie Plain contains abundant clay, although in some areas it is quiet sandy where ancient beaches formed.[1] Beneath this relatively thin layer of soil is unconsolidated moraine, soil and rock left behind as the glaciers retreated.[8]

Description

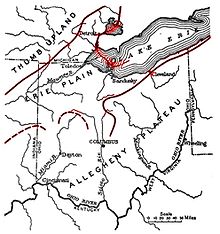

editThree geologically distinct plains border Lake Erie. The lowest of these is the Ontario Plain, followed by the Huron Plain and then the Erie Plain. Escarpments separate the plains from one another. Between the Erie Plain and the Appalachian Plateau is the Portage Escarpment.[9]

The Erie Plain begins just east of Auburn, New York, where the Onondaga Escarpment meets the Portage Escarpment.[10] The Onondaga Escarpment sharply distinguishes the Erie Plain from the Huron Plain east of Buffalo. But along the southern side of Lake Erie west of Buffalo, the Onondaga Escarpment is so slight that the Huron Plain and Erie Plain are essentially the same.[11][12] At Buffalo, the plain narrows to just 2 to 3 miles (3.2 to 4.8 km) wide as the Portage Escarpment moves closer to the Lake Erie shoreline,[13] and remains 2 to 4 miles (3.2 to 6.4 km) wide in Erie County, Pennsylvania.[14] From Erie, Pennsylvania, to Cleveland, the plain broadens to about 4 to 6 miles (6.4 to 9.7 km)[2] and is starkly defined by the Portage Escarpment,[15] which rises in three terraces.[16][17] The plain remains narrow until just west of Cleveland, where the Portage Escarpment moves to the south,[10] and the definition between the plain and escarpment becomes much less distinct.[18] The escarpment is broken in two places by the valleys of the Great Miami and Scioto rivers.[17][19] The plain expands to 4 to 5 miles (6.4 to 8.0 km) between the Cuyahoga River and the Rocky River, and to 17 miles (27 km) west of the Rocky River around the southwest and western sides of Lake Erie.[20] All told, the Erie Plain covers about one-fourth of the state of Ohio.[17] The Erie Plain extends into Michigan[1] where the Marshall Escarpment forms the inland boundary between the Erie Plain and the interior uplands.[21] The Erie Plain also covers most of the Southern Ontario peninsula between Lake Erie and Lake Huron. Here, the Niagara Escarpment separates the Erie Plain from the Huron Plain to the north.[10]

In Ohio, the combined Huron-Erie Plain begins at a mean altitude of 573 feet (175 m) above sea level, and gradually rises in a series of slight, rolling hills to more than 1,000 feet (300 m) above sea level. In Ontario, post-glacial rebound has lifted the Huron Plain in the north higher than the Erie Plain in the south. South of Georgian Bay, the Niagara Escarpment lifts the Huron Plain to more than 1,500 feet (460 m) above sea level.[10]

The Erie Plain lacks distinguishing features, except for occasional recessional moraines, and the remnants of proglacial lake beaches and lakeside cliffs.[10][17] In Pennsylvania, the plain is marked only by a series of slight terraces; the boundary between each marks ancient lake shorelines.[14] Cushing, Leverett, and Van Horn identify at least three moraines between Erie, Pennsylvania, and Ohio's Rocky River: The Cleveland, the Euclid, and the Defiance.[11] West of the Rocky River are three ridges (the North, Middle, and Butternut) roughly paralleling the modern lakeshore, ancient beaches formed by proglacial expansions of Early Lake Erie.[20] In Indiana, the lack of distinguishing features allows the plain to merge with the Mississippi River basin lowlands.[21] On the Niagara Peninsula, morainic ridges interrupt the Erie Plain close to the Niagara Escarpment, as well as a few east–west flowing river valleys.[22]

Settlement and economic development

editThe Erie Plain connects with the Mohawk Valley in the east, and provides the only natural, low-lying route north of the Gulf Coast to the North American interior from the Atlantic seaboard. Consequently, this area is heavily populated.[18] The city of Cleveland is largely built on sediments which form the Erie Plain.[23]

The Welland Canal cuts north–south across the Erie Plain on the Niagara Peninsula. The Deep Cut on the canal, between Allanburg, and Port Robinson, has created two distinct economic districts in the area. The northern district connects with shipping on Lake Ontario, while the southern district is much more aligned with shipping on Lake Erie.[24]

Settlement of Ohio largely occurred along the Erie Plain, following the natural barrier of the Portage Escarpment. In the far northwest of the state, settlement was inhibited by the poorly drained portion of the Erie Plain known as the Great Black Swamp. This area was heavily forested, but nearly all of this primeval forest (representing half of Ohio's woodlands) was clear-cut by 1900.[25] Although the Erie Plain was Ohio's richest farmland, it was also its least forested by the start of the 20th century.[26] Viticulture on the Erie Plain in Ohio has been extensive, both due to the fertile soil and the temperate climate.[27]

Watershed

editLake Erie essentially occupies a depression in the middle of the Erie Plain,[9] with the plain tilted toward the lake.[17] The watershed in Ohio is about 12,000 square miles (31,000 km2).[17][a]

The Erie Plain drains into Lake Erie, except for that portion east of Buffalo (which drains into Lake Ontario).[3] Water on the Appalachian Plateau, on the other hand, drains to the Gulf of Mexico.[29] In Ohio, brooks generally cut into the plain 10 to 40 feet (3.0 to 12.2 m), while rivers dig channels 40 to 100 feet (12 to 30 m) deep.[20] The plain is so narrow in Ohio that it has no watershed distinct from that which forms in the Portage Escarpment.[30] The Erie Plain in extreme northwest Ohio is not as well-drained as that in the rest of the state, as glacial moraines partially block water in the area.[17] This area was previously known as the Great Black Swamp, until drained by white settlers in the 1800s.[25]

Much of the Erie Plain lies beneath Lake Erie,[11] which has a relatively shallow average depth of just 62 feet (19 m).[31]

Climate

editFrom the beginning of recordkeeping in the early 1800s to 1921, the average rainfall on the plain was about 34 inches (86 cm) a year, with the rainiest months being June and July and the driest October.[32] Prior to human settlement, the combination of landform and rainfall left the Erie Plain with typical prairie plants.[33] Marshes and shallow lakes formerly dotted the landscape here, but human-caused drainage since 1800 has largely erased these and left highly fertile plains behind.[17] Southeastern Michigan, however, still contains many of these distinctive hardwood forest swamps and marshy prairies.[34]

The relatively flat nature of the plain presents little inhibition to wind and the flow of weather across the plain. However, the large cities which line Lake Erie tend to create urban heat islands which can cause local instabilities.[35] Lake Erie itself, however, tends to lessen the effects of cold arctic air masses coming from the north, making the Erie Plain more temperate.[27]

See also

editProglacial lakes of the Lake Erie Basin

References

edit- Notes

- ^ The Wisconsin glaciation is primarily responsible for the drainage patterns in Ohio. At first, the glaciers extended southward across most of Ohio. As they retreated, water shed from the glaciers carved channels southward to the Ohio River. When the glaciers retreated beyond the Portage Escarpment, water was trapped between the glaciers and the Portage Escarpment, creating ever-larger lakes. As the glaciers retreated northward again, the water found an outlet through the St. Lawrence River, carving new drainage valleys through the lake-facing side of the escarpment and the Erie Plain.[28]

- Citations

- ^ a b c Barnes & Wagner 2004, p. 372.

- ^ a b New York State Department of Transportation 1983, p. 22.

- ^ a b Cushing, Leverett & Van Horn 1931, p. 4.

- ^ Wilder, Maynadier & Shaw 1911, pp. 200–201.

- ^ Cushing, Leverett & Van Horn 1931, pp. 5–6, 34.

- ^ Cushing, Leverett & Van Horn 1931, p. 5.

- ^ Cushing, Leverett & Van Horn 1931, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Hubbard et al. 1915, p. 13.

- ^ a b Cushing, Leverett & Van Horn 1931, pp. 2–3.

- ^ a b c d e Cushing, Leverett & Van Horn 1931, p. 3.

- ^ a b c Cushing, Leverett & Van Horn 1931, p. 14.

- ^ New York State Air Pollution Control Board 1961, p. 58.

- ^ Cushing, Leverett & Van Horn 1931, pp. 3, 14.

- ^ a b Wilder, Maynadier & Shaw 1911, p. 200.

- ^ Tesmer & Bastedo 1981, p. 7.

- ^ Cushing, Leverett & Van Horn 1931, pp. 13–14.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Waller 1921, p. 48.

- ^ a b Cushing, Leverett & Van Horn 1931, p. 10.

- ^ Hubbard et al. 1915, pp. 10–11.

- ^ a b c Cushing, Leverett & Van Horn 1931, p. 15.

- ^ a b Hubbard et al. 1915, p. 9.

- ^ Jackson 1997, p. 7.

- ^ Cushing, Leverett & Van Horn 1931, p. 18.

- ^ Jackson 1997, p. 227.

- ^ a b Whitney 1994, p. 154.

- ^ Whitney 1994, pp. 154–155.

- ^ a b Hasenstab 2007, p. 169.

- ^ Hubbard et al. 1915, pp. 18–19.

- ^ Hubbard et al. 1915, p. 11.

- ^ Cushing, Leverett & Van Horn 1931, pp. 20–21.

- ^ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (March 9, 2006). "Great Lakes Factsheet No. 1" (PDF). National Research Council. Retrieved July 4, 2015.

- ^ Waller 1921, p. 52.

- ^ Waller 1921, p. 55.

- ^ Barnes & Wagner 2004, p. 379.

- ^ New York State Air Pollution Control Board 1961, p. 59.

Bibliography

edit- Barnes, Burton Verne; Wagner, Warren H. (2004). Michigan Trees: A Guide to the Trees of the Great Lakes Region. Ann Arbor, Mich.: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 9780472089215.

- Cushing, Henry Platt; Leverett, Frank; Van Horn, Frank R. (1931). Geology and Mineral Resources of the Cleveland District, Ohio. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office.

- Hasenstab, Robert J. (2007). "Aboriginal Settlement Patterns in Late Woodland Upper New York State". In Kerber, Jordan E. (ed.). Archaeology of the Iroquois: Selected Readings and Research Sources. Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 9780815631392.

- Hubbard, George D.; Stauffer, Clinton R.; Bownocker, John Adams; Prosser, Charles Smith; Cumings, Edgar Rosecoe (1915). Geologic Atlas of the United States, Issue 197. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Geologic Survey.

- Jackson, John N. (1997). The Welland Canals and Their Communities: Engineering, Industrial, and Urban Transformation. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 9780802009333.

- New York State Air Pollution Control Board (1961). Area Survey. Vol. 1 (Report). Albany, N.Y.: New York State Air Pollution Control Board.

- New York State Department of Transportation (1983). Southern Tier Expressway Study, Project Report II, Hinsdale, N.Y. to Erie, Pa (Report). Albany, N.Y.: N.Y. State Department of Transportation.

- Tesmer, Irving H.; Bastedo, Jerold C. (1981). Colossal Cataract: The Geologic History of Niagara Falls. Albany, N.Y.: State University of New York Press. ISBN 9780873955225.

- Waller, Adolph Edward (1921). The Relation of Plant Succession to Crop Production, a Contribution to Crop Ecology. Columbus, Ohio: The Ohio State University.

- Whitney, Gordon Graham (1994). From Coastal Wilderness to Fruited Plain: A History of Environmental Change in Temperate North America, 1500 to the Present. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521576581.

- Wilder, Henry J.; Maynadier, Gustavus B.; Shaw, Charles F. (1911). "A Reconnaissance Survey of Northwest Pennsylvania". In Whitney, Milton (ed.). Field Operations of the Bureau of Soils, 1908. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office.