Elliott Lewis (November 28, 1917 – May 23, 1990)[1] was an American actor, writer, producer, and director who worked in radio and television during the 20th century. He was known for his ability to work in these capacities across all genres during the golden age of radio, which earned him the nickname "Mr. Radio".[2][3][4][5] Later in life, he wrote a series of detective novels.[6]

Elliott Lewis | |

|---|---|

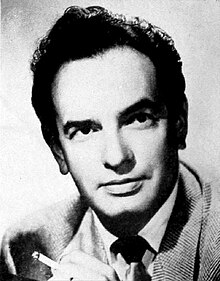

Elliott Lewis in 1954. | |

| Born | November 28, 1917 New York City, U.S. |

| Died | May 23, 1990 (aged 72) Portland, Oregon, U.S. |

| Occupations |

|

| Spouse | Ann "Nana" Wigton (m. August 30, 1940; annulled Sept. 1940)

Cathy Lewis (m. 1943; div. 1958) Mary Jane Croft (m. 1959) |

Early years

editElliott Bruce Lewis was born in New York City, on November 28, 1917, to Julius Lewis and Anne Rabinowitz Lewis.[7] His father was a printer.[8][9] He had one younger brother, Raymond.[10] By 1930, the family was living in Mount Vernon, New York.[9] Lewis headed west to Los Angeles to take a prelaw course in his 20s, but found himself drawn to acting. He attended Los Angeles City College, where he studied music and drama.[11]

Radio career

editLewis made his radio debut in 1936, at the age of 18. While Lewis was a student at Los Angeles CIty College, True Eames Boardman noticed him in a college play and invited him to read four lines in a biography of Simon Bolivar that Boardman was producing for Sunday Workshop.[12] Lewis' role was to scream and bang metal chairs in an earthquake scene. His mother drove him to the NBC studio, kissed him for luck, and waited in the car with the radio on. At the moment of her son's debut, a streetcar rumbled by, preventing her from hearing his big scene.[13] Another of his early roles was as Mr. Presto the Magician, on the transcription series The Cinnamon Bear (1937).[14] In 1939, he became the host of Knickerbocker Playhouse.[15]: 190–91 [16][17]

As an actor, Lewis was in high demand on radio, and he displayed a talent for everything from comedy to melodrama. He gave voice to the bitter Harvard-educated Soundman on the 1940–41 series of Burns and Allen and several characters (Rudy the radio detective, the quick-tempered delivery man, and Joe Bagley) on the 1947–48 series, many characters on The Jack Benny Radio Show (including the thuggish "Mooley", and cowboy star "Rodney Dangerfield"), a variety of characters on the Parkyakarkus show,[18] and Rex Stout's roguish private eye Archie Goodwin, playing opposite Francis X. Bushman in The Amazing Nero Wolfe (1945).[15][16] Lewis was one of several actors who had the title role in The Casebook of Gregory Hood,[15]: 66 [17] and he portrayed the title character in Hawk Durango.[15]: 147 He played Harry Graves on Junior Miss,[15]: 185–86 [16][17] Barney Dunlap on Speed Gibson of the International Secret Police,[15]: 311–12 [16] Mr. Peterson on This Is Judy Jones,[14]: 664 and adventurer Phillip Carney on the Mutual Broadcasting System's Voyage of the Scarlet Queen[15]: 348 [16][17]

Lewis was an announcer on Escape.[15]: 110 He was also heard as an actor on episodes of Adventures by Morse,[14]: 6–7 The Adventures of Maisie (1946–47),[16][17] The Adventures of Sam Spade,[14]: 12 Arch Oboler's Plays,[14]: 37 Best of the Week,[19] The Clock,[14]: 160 Columbia Presents Corwin,[14]: 167 [3][17] The Hermit's Cave,[14]: 318–19 I Love a Mystery,[14]: 337 [16][17] Latitude Zero,[19] Orson Welles Theater,[14]: 525 Plays for Americans[14]: 548 Suspense,[20] The Whistler,[20] and dozens of other shows. He found acting, except for comedy, dull, and he preferred to write and to direct.[21] He disliked hearing his own voice.[6]

He also taught radio classes at UCLA in the early 1950s.[13][22][12]

Military service

editDuring World War II, Lewis was a master sergeant who produced 120 shows for the Armed Forces Radio Network.[13] Much of his work involved recording programs from commercial networks and editing them before they were broadcast to military personnel. Lewis said, "We would take them off the air, take out anything that dated them or was commercial or censorable, reassemble them, and ship them."[23] In an era that preceded tape recording, that meant working with transcriptions on glass discs, which could easily be broken.[23] Lewis received the Legion of Merit citation for his service.[1][24] He left the Army on February 1, 1946, following three and a half years of service.[20]

The Phil Harris–Alice Faye Show

editPerhaps Lewis' most famous role on radio was that of the hard-living, trouble-making, left-handed guitar player Frankie Remley on NBC's The Phil Harris-Alice Faye Show.[1][3] This character, based in name only on the actual guitar player in Harris' band, served only one purpose - to get Phil into trouble.[3] Lewis's portrayal of the character, along with the rest of the Harris-Faye format, began on The Fitch Bandwagon (1946–48).[14]: 254 Lewis was credited with saving the role, which had been filled by the real Frankie Remley for one episode.[25]

Jeanine Roose, who portrayed Alice Jr. on the program, described Lewis as a "totally extroverted wild man," adding, "He and Phil would play off each other all the time; they had such good rapport and a genuine liking for each other."[26] Lewis said that, though he mostly played dramatic roles, he wished he could be a baggy-pants comic.[27]

The name "Frankie Remley" belonged to Harris's guitarist on The Jack Benny Program, on which Harris was a cast member.[28] Frankie Remley taught Lewis to play a few guitar chords[29] and allowed Lewis, who, like Remley, was left handed, to use Remley's left-handed guitar for one episode.[6]

When Benny moved his show from NBC to CBS in 1949, rights to use references to Remley supposedly went with him.[6] Recordings of the shows indicate, however, that the Remley character was still used at least as late as April 12, 1952, (in the episode "Alice's Easter Dress") while "Elliott Lewis" was being used for the character in the November 23, 1952, episode ("Chloe the Golddigger"). Harris left Benny's show at the end of the 1951–52 season, and the Frankie Remley name was changed in the first episode of the 1952–53 season of the Harris-Faye Show (October 5, 1952), "Hotel Harris", in which the character claimed "Frankie Remley" was just his stage name, and he now wanted to go by his given name of "Elliott Lewis". According to Lewis, the name change happened after lawyers convinced the real Remley to seek payment for the use of his name. Lawyers for both sides fought it out, until Harris, in frustration, decided to just call the character "Elliott Lewis". Lewis observed, "Frankie Remley" is a funny-sounding name, but "Elliott Lewis" is not.[6]

Radio production

editThe first radio script Lewis wrote was for Hermit's Cave ("The Drain"). Lewis' writing process involved thinking of a provocative sound or circumstance.[20]

He was considered one of the top talents in the radio world. In all, Lewis was involved in over 1200 radio productions, often working behind and in front of the microphone on the same episodes. Lewis took over directorship of Suspense from William Spier in 1950.[30] One noteworthy undertaking is his adaptation of William Shakespeare's Othello on Suspense in 1953. Lewis adapted, acted in, produced, and directed; his wife, Cathy, played Desdemona.[22][31] He received positive notice for episodes like "The Death of Barbara Allen".[32]

Lewis said he disagreed with studio executives and sponsors who, he said, would ask for changes to a script shortly before a show was to record. On his desk was a mug with a question printed that Lewis had heard from Fred Allen: "Where were you when the page was blank?" He would turn to face people who entered his office requesting many changes to scripts.[6] When studio executives tried to get a 1951 Suspense, "Murder in G-flat", which was to star Jack Benny, scrapped because they believed it was neither suspenseful nor funny, Lewis insisted on proceeding with the production, and it was a success.[6][33]

In 1946, Lewis and 26 other veterans who had worked in the AFRS joined forces to form Command Radio Productions for the creation of both transcribed and live radio programs. Lewis was second vice president of the company, which had offices in Hollywood and New York City.[34] Lewis remarked to Shirley Gordon of Radio Life: "Writing's fun. You can do it at home in your pajamas. You don't have to get dressed up and go some place."[20] He wrote episodes of many radio shows, including Suspense ("Can't We Be Friends?" and "My Dear Niece"),The Whistler ("Accident According to Plan), and Twelve Players.[20] As a producer, director, and writer, Lewis was a force behind such radio programs as The Lineup,[15]: 201–02 Mr. Aladdin,[14]: 462 Pursuit[14]: 555 Suspense,[14]: 647 [16][3][17] Broadway Is My Beat,[16] Crime Classics, and numerous other shows.[14]

Lewis and his wife, Cathy Lewis, had wanted a half-hour weekly show over which they had creative control since at least 1946.[20] Beginning January 1, 1953, Lewis and Cathy co-starred in the character-driven anthology series On Stage on CBS.[16] Lewis also produced and directed the show over its two seasons.[35][14]

Lewis was against adapting movies for radio. "Material written for one medium shouldn't be used on an other. How can a story planned for 90 minutes of sight dimension be told in 21 minutes of sound?" He also believed that many movie stars were not suited for the work because they were uncomfortable performing for radio.[20] Both Lewises believed in name billing for all radio performers. "We think the listeners want to know whom they are hearing on their radios, and if radio isn't willing to 'build up' its own people, it is only hurting itself."[20]

Films and records

editLewis did work in film, although radio was his great passion, and he claimed to become extremely nervous in front of cameras.[12] On the big screen, he played the distraught father of a child killed in a car accident in The Devil on Wheels (1947), narrated The Winner's Circle (1948), and portrayed Rod Markle in The Story of Molly X (1949). He also appeared as a police officer in Ma and Pa Kettle Go to Town (1950), and as reporter Eddie Adams in Saturday's Hero (1951). He was tested for the title role in Jesse Lasky's The Great Caruso film.[36] The role ultimately went to Mario Lanza.

Lewis served as narrator and male lead of Gordon Jenkins' musical narrative album Manhattan Tower in both the original 10-inch LP and the later recorded, expanded 12-inch LP version of the musical story.[37]

Lewis and his second wife, Cathy, released two musical story albums orchestrated by Ray Noble: Happy Anniversary[38][39] (Columbia MC-160)[40] and Happy Holidays.[41] Lewis reported that though the records never made much money, years later, he learned that they were played annually by the CBS affiliate station in St. Louis, KMOX.[6]

Television

editThough he was initially critical of television,[42] Lewis began to work in the medium in the final years of the golden age of radio. Lewis was an announcer for the television series Escape, the visual counterpart of the radio program of the same name.[43] Lewis appeared on television only twice: with Phil Harris on an episode of All Star Revue,[44] and as a judge on episode two of the 1975 Sheldon Leonard sitcom Big Eddie.[45]

As the Golden Age of Radio ended, Lewis shifted his focus to television production, where he began by co-producing Climax and Kraft Television Theatre.[1] In 1953, Cathy Lewis, E. Jack Neuman, Irene M. Neuman, and he formed a radio and television production company, Hawk-Lewis Enterprises.[46] Lewis was one of three members of a "board of revue" established by NBC-TV to oversee development of color programming in 1955. Milt Josefsberg, Jess Oppenheimer, and he evaluated and supervised pilots of color programs and oversaw a development program for new writers.[47]

In 1956, he was executive producer of Tomado Productions' Crime Classics, a TV version of the radio program of the same title.[48]

By the 1960s, Lewis was directing such shows as The Mothers-in-Law,[49] Petticoat Junction, and Bill Cosby's and Andy Griffith's programs. He was director, producer, and writer for Bat Masterson, MacKenzie's Raiders, and This Man Dawson.[1] before producing Guestward Ho and The Lucy Show[1] (on which his wife Mary Jane Croft costarred as Lucy's sidekick Mary Jane Lewis – her married name).[4] He was promoted to executive producer of The Lucy Show for its 1963–1964 season[50] and stepped down at the end of that season.[51] Lewis joined Bing Crosby Productions in 1964 to work on new projects.[52]

His final credited work was as an executive script consultant for Remington Steele.[10]

Revival of radio

editIn the 1970s, Lewis produced radio dramas during a brief reincarnation of the medium. In 1973–74, he produced and directed Mutual's The Zero Hour, hosted by Rod Serling.[14]: 744 [53]

In 1979, Fletcher Markle and he produced the Sears Radio Theater, with Sears as the sole sponsor. Lewis wrote the episodes "The Thirteenth Governess" and "Cataclysm at Carbon River" (the latter was pulled by CBS due to its subject matter of a nuclear disaster, and was never aired), and acted on the episodes "Getting Drafted", "The Old Boy", "Here's Morgan Again", "Here's Morgan Once More", and "Survival".[54]

In 1980, the series moved from CBS to Mutual and was renamed The Mutual Radio Theater, sponsored by Sears and other sponsors. Lewis scripted the episodes "Yes Sir, That's My Baby"[55] and "Our Man on Omega",[56] and acted on the episodes "Interlude",[57] "Night",[58] "Hotel Terminal",[59] and "Lion Hunt".[60]

Novelist

editIn his later years, Lewis wrote seven detective novels about Fred Bennett, a police officer who becomes a private investigator. The series was published by Pinnacle Books from 1980 to 1983.

- Two Heads Are Better (1980) ISBN 0523414390

- Dirty Linen (1980) ISBN 0523406533

- People in Glass Houses (1981) ISBN 0523414374

- Double Trouble (1981) ISBN 0523414382

- Bennett's World (1982) ISBN 0523415931

- Here Today, Dead Tomorrow (1982) ISBN 0523414390

- Death and the Single Girl (1983) ISBN 0523414773

Death and the Single Girl was nominated for a Shamus Award for Best Original P.I. Paperback from the Private Eye Writers of America in 1984, but lost to Dead in Centerfield by Paul Engelman.[61]

Personal life

editLewis was an avid reader. He enjoyed playing the piano and cooking.[13][20] He was a stamp collector and his collection contained some stamps from Franklin Delano Roosevelt's collection.[20]

Marriages

editOn August 30, 1940, Lewis eloped to Las Vegas with surfer and model Ann "Nana" Wigton. Five days later, they separated. Wigton filed for an annulment on the grounds that Lewis had tricked her into marriage by falsely claiming he wanted to start a family. The annulment was granted a month later.[62]

Lewis met singer and actress Cathy Lewis (who had the same surname before their marriage) as they recorded at The Woodbury Playhouse on November 6, 1940.[20] On April 30, 1943, while on leave from the Army, Lewis married Cathy Lewis at Chapman Park Hotel in Los Angeles. Lewis' uncle Eddie Raiden was best man.[63] Together, the couple worked on such old time radio classics as Voyage of the Scarlet Queen and Suspense. They earned a combined income of $90,000 per year.[22] The Lewises separated on their 14th anniversary, and Cathy filed for divorce, on the grounds of mental cruelty. The divorce was granted on April 16, 1958.[64]

In the spring of 1959, Lewis married actress Mary Jane Croft, and they remained together until Lewis' death from cardiac arrest at his home in Gleneden Beach, Oregon, on May 23, 1990.[10][1] His stepson Eric Zoller, from Croft's first marriage, was killed in Vietnam on January 22, 1967.[65][66]

Honors

editHe was nominated for induction to the National Radio Hall of Fame in 1999, but was not inducted.[67]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f g Oliver, Myrna (May 26, 1990). "Eliott Lewis; Actor, Producer, Mystery Writer". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on April 19, 2019. Retrieved January 31, 2020.

- ^ "The Cathy and Elliott Lewis On Stage Radio Program".

- ^ a b c d e Nachman, Gerald (2000). Raised on radio : in quest of the Lone Ranger (1st paperback ed.). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-22303-9. OCLC 43185889.

- ^ a b Sheridan, James; Monush, Barry (2011). Lucille Ball FAQ : everything left to know about America's favorite redhead. Milwaukee, WI: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-55783-933-6. OCLC 946707338.

- ^ "Information" (PDF). Radio TV Mirror. January 1954. p. 18. Retrieved February 24, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Dunning, John. Interview with Elliott Lewis. May 23, 1982.

- ^ "Lewis, Elliott Bruce". Contemporary Authors. 2003 – via Gale Literature.

- ^ Federal Census, United States census, 1920; Manhattan Assembly District 23, New York, New York; roll T625_1227, page 23B, line 43, enumeration district 1502.

- ^ a b Federal Census, United States census, 1930; Mount Vernon, Westchester, New York; roll FHL microfilm 2341396, page 14A, line 9, enumeration district 0218. Retrieved on February 26, 2020.

- ^ a b c "Obituaries". Variety. June 13, 1990. p. 92 – via Proquest.

- ^ DeLong, Thomas A. (1996). Radio Stars: An Illustrated Biographical Dictionary of 953 Performers, 1920 through 1960. McFarland & Company, Inc. ISBN 978-0-7864-2834-2. p. 165.

- ^ a b c Steinhauser, Si (November 28, 1950). "Miss Lewis Met Mr. Lewis and Cupid Saw Stars". The Pittsburgh Press. Retrieved March 3, 2020.

- ^ a b c d "Elliott Lewis – He's Known As 'Mr. Radio'". The Ottawa Citizen. Canada, Ottawa, Ontario. September 12, 1953. p. 26. Retrieved January 30, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Dunning, John (1998). On the Air: The Encyclopedia of Old-Time Radio. Oxford University Press. p. 154. ISBN 978-0-19-977078-6. Retrieved January 29, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Terrace, Vincent (1999). Radio Programs, 1924–1984: A Catalog of More Than 1800 Shows. McFarland & Company, Inc. pp. 12–13. ISBN 978-0-7864-4513-4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Lackmann, Ronald W. (2000). The encyclopedia of American radio : an A–Z guide to radio from Jack Benny to Howard Stern. Lackmann, Ronald W. (Updated ed.). New York: Facts On File. ISBN 0-8160-4137-7. OCLC 41531878.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Buxton, Frank; Owen, Bill (1972). The Big Broadcast: 1920–1950. New York: Flare Books.

- ^ Nesteroff, Kliph (2015). The comedians : drunks, thieves, scoundrels, and the history of American comedy (1st ed.). New York: Open Road + Grove/Atlantic. ISBN 978-0-8021-2398-5. OCLC 921844606.

- ^ a b Abbott, Sam (September 6, 1941). "Hollywood" (PDF). Billboard. p. 7. Retrieved January 31, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Gordon, Shirley (November 3, 1946). "Radio A La Lewis" (PDF). Radio Life. Retrieved February 24, 2020.

- ^ Bertel, Dick; Corcoran, Ed (August 1977). "Elliott Lewis Interview". The Golden Age of Radio. Hartford, Connecticut.

- ^ a b c "Full Steam Ahead". Time. May 18, 1953. Archived from the original on December 22, 2008. Retrieved February 1, 2020.

- ^ a b Elliott, Jordan (Autumn 2017). "Mr. Radio". Nostalgia Digest. 43 (4): 26–31.

- ^ Bigsby, Evelyn (September 28, 1947). "The Voyage of the Scarlet Queen" (PDF). Radio Life. p. 7. Retrieved February 24, 2020.

- ^ "Radio Sidelights: Elliott Lewis Steps in to Save a Part, Make It a Hit". Kansas City Star. March 27, 1949. p. 12E – via Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Elder, Jane Lenz (2002). Alice Faye: A Life Beyond the Silver Screen. Univ. Press of Mississippi. p. 194. ISBN 978-1-57806-210-2. Retrieved October 7, 2017.

- ^ Ames, Walter (March 15, 1954). "Producers Admit They Are Really a Bunch of Very Frustrated Hams". Los Angeles Times. California, Los Angeles. p. Part I p 30. Retrieved January 31, 2020.

- ^ "Obituaries". Variety. Vol. 254, no. 11. February 1, 1967. p. 79 – via Proquest.

- ^ Maguire, Judy (January 23, 1949). "If Phil's Ever in a Jam" (PDF). Radio Life. pp. 4, 32. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- ^ Ames, Walter (June 20, 1950). "Television Radio Programs: Elliott Lewis Will Replace Spier on 'Suspense'". Los Angeles Times. p. 18 – via Proquest.

- ^ "Radio Reviews". Variety. May 13, 1953. p. 34 – via Proquest.

- ^ "Radio in Review: Your Cue: Shows You May Like: Suspense" (PDF). TV-Radio Life. October 31, 1952. pp. 22, 24. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- ^ "Radio-Television: Radio Followup". Variety. Vol. 182, no. 5. April 11, 1951. p. 40 – via Proquest.

- ^ "New Package Firm" (PDF). Broadcasting. July 29, 1946. p. 72. Retrieved February 4, 2020.

- ^ "air-casters" (PDF). Broadcasting. January 5, 1953. p. 54. Retrieved July 16, 2016.

- ^ Jones, Will (April 28, 1947). "Eyes Get Moist at 'Sea of Grass'". Star Tribune. Minnesota, Minneapolis. p. 18. Retrieved January 31, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Jenkins, Gordon. Complete Manhattan Tower. Capitol Records, 1956. T-766.

- ^ Ray Noble and His Orchestra. Happy Anniversary (A Musical Story). With Cathy and Elliott Lewis. Columbia Records, 1948. CL 6011.

- ^ "Vox Jox". The Billboard. January 22, 1949. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- ^ "Album Reviews" (PDF). Billboard. June 12, 1948. p. 36. Retrieved February 3, 2020.

- ^ Ray Noble and His Orchestra. Happy Holidays: A Musical Story. With Cathy and Elliott Lewis. Columbia Records, 1949. CL 6053.

- ^ Humphrey, Hal (February 7, 1954). "Radio Freed from Chains Says Elliott Lewis". Detroit Free Press. p. 110. Retrieved March 3, 2020.

- ^ Terrace, Vincent (2011). Encyclopedia of Television Shows, 1925 through 2010 (2nd ed.). Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers. p. 311. ISBN 978-0-7864-6477-7.

- ^ "Radio-Television: Harris-Fronted 'Revue' Adds to Talent Roster". Variety. Vol. 192, no. 11. November 18, 1953. p. 34 – via Proquest.

- ^ Schaden, Chuck. "Interviews: Elliot [sic] Lewis. Speaking of Radio. August 27, 1975. Retrieved February 2, 2020.

- ^ "Production Shorts: Hawk-Lewis Enterprises". Broadcasting, Telecasting. Vol. 45, no. 25. December 21, 1953. p. 100 – via Proquest.

- ^ "NBC-TV Bears Down On Color Programs" (PDF). Billboard. October 22, 1955. p. 8. Retrieved February 3, 2020.

- ^ "Tomado to Film 2 New Series" (PDF). Billboard. March 24, 1956. p. 2. Retrieved February 3, 2020.

- ^ Tucker, David C. (2014). Eve Arden: A Chronicle of All Film, Television, Radio and Stage Performances. McFarland. pp. 158–166. ISBN 978-0-7864-8810-0. Retrieved January 31, 2020.

- ^ "Promoted on Lucy Show". Boxoffice. Vol. 83, no. 23. September 30, 1963. p. W-2 – via Proquest.

- ^ "Radio-Television: Elliott Lewis Exits As Lucy's Exec Producer". Variety. Vol. 234, no. 5. March 25, 1964. p. 25 – via Proquest.

- ^ "Programing" (PDF). Broadcasting. April 6, 1964. p. 160. Retrieved February 5, 2020.

- ^ "Radio's 'Zero Hour' Starts Monday". Santa Ana Register. August 30, 1973. p. C6 – via NewspaperArchive.

- ^ Cox, Jim (2009). American Radio Networks: A History. McFarland. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-7864-5424-2. Retrieved October 7, 2017.

- ^ "Yes, Sir, That's My Baby at RadioEchoes.com". www.radioechoes.com. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ^ "The Man from Omega at RadioEchoes.com". www.radioechoes.com. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ^ "Generic Radio Workshop OTR Script: Mutual Radio Theatre". www.genericradio.com. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ^ "Night at RadioEchoes.com". www.radioechoes.com. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ^ "Hotel Terminal at Generic Radio Workshop OTR Script: Mutual Radio Theatre". www.genericradio.com. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ^ "Lion Hunt at RadioEchoes.com". www.radioechoes.com. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ^ Death and the Single Girl by Elliot Lewis. Retrieved January 12, 2019.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ "Divorce news". Tulare Advance-Register. California, Tulare. September 26, 1940. p. 2. Retrieved January 31, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Lewis, Elliott. "Young Married World". Retrieved January 30, 2020.

- ^ "Irma's Friend, Husband Split". The Victoria Advocate. Texas, Victoria. Associated Press. April 17, 1958. p. 18. Retrieved January 31, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Obituaries". Variety. August 30, 1999. p. 166 – via Proquest.

- ^ "Obituaries". Variety. February 22, 1967. p. 71 – via Proquest.

- ^ "Newsbreakers: Radio Hall Of Fame Selects Nominees". R&R. No. 1290. Los Angeles. March 12, 1999. p. 16 – via Proquest.

External links

edit- Elliott Lewis at IMDb

- Elliott Lewis radio credits at the Radio GOLDINdex

- Elliott Lewis radio programs