Agnes Elisabeth Lutyens, CBE (9 July 1906 – 14 April 1983) was an English composer.

Elisabeth Lutyens | |

|---|---|

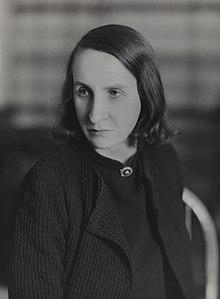

Lutyens in 1939 (from the National Portrait Gallery) | |

| Born | 9 July 1906 London, England |

| Died | 14 April 1983 (aged 76) London, England |

| Occupation | Composer |

| Spouses | |

| Children | 4 |

| Parent(s) | Edwin Lutyens Lady Emily Bulwer-Lytton |

| Relatives | Mary Lutyens (sister) Matthew White Ridley, 4th Viscount Ridley (nephew) Nicholas Ridley (nephew) |

Early life and education

editElisabeth Lutyens was born in London on 9 July 1906. She was one of the five children of Lady Emily Bulwer-Lytton (1874–1964), a member of the aristocratic Bulwer-Lytton family, and the prominent English architect Sir Edwin Lutyens. Elisabeth was the elder sister of the writer Mary Lutyens[1] and aunt of the 4th Viscount Ridley and the politician Nicholas Ridley.

Lutyens was involved in the Theosophical Movement. From 1911 the young Jiddu Krishnamurti was living in the Lutyens' London house as a friend of Elisabeth and her sisters. At the age of nine she began to aspire to be a composer. In 1922, Lutyens pursued her musical education in Paris at the École Normale de Musique, which had been established a few years previously, living with the young theosophical composer Marcelle de Manziarly, who had been trained by Nadia Boulanger. During her months in Paris Lutyens showed first signs of depression that later led to several mental breakdowns.[2]

She accompanied her mother to India in 1923. On her return to Europe she studied with John Foulds and subsequently continued her musical education from 1926 to 1930 at the Royal College of Music in London as a pupil of Harold Darke.[1]

Family life

editIn 1933, Lutyens married baritone Ian Glennie; they had twin daughters, Rose and Tess, and a son, Sebastian.[3] The marriage was not happy, however, and in 1938 she left Glennie. They divorced in 1940.[1]

She then became the partner of Edward Clark, a conductor and former BBC producer who had studied with Schoenberg. Clark and Lutyens had a son, Conrad, in 1941 and married on 9 May 1942.[3] She composed in complete isolation, a process greatly impeded by the drinking and partying at the Clark flat, and the responsibilities of motherhood.[1]

In 1946, pressured by Edward Clark and her mother, she decided to abort her fifth child. Two years later, she had a mental and physical breakdown that forced her to spend several months in a mental health institution. It was not until 1951 that she managed to regain control of her alcohol addiction, having endured days of extreme withdrawal.[4]

Lutyens was interviewed, in June 1975, by the historian, Brian Harrison, as part of the Suffrage Interviews project, titled Oral evidence on the suffragette and suffragist movements: the Brian Harrison interviews.[5] She reflected on theosophy and its influence on women’s suffrage, lesbianism in the suffrage movement and Edwardian attitudes towards sex and contraception, as well as her mother’s family relationships, including with Lady Constance Lytton.

Career

editWorks

editIn 1945, William Walton was able to repay the service Clark had rendered him in relation to the premiere of his Viola Concerto in 1929. Lutyens approached Walton for an introduction to Muir Mathieson with a view to getting some film music work. He readily agreed to pass on her name, but he went a step further: He invited her to write any work she liked, then dedicate it to him, and he would pay her £100 sight unseen. The work she wrote was The Pit.[6] Edward Clark conducted The Pit at the 1946 ISCM Festival in London, along with her Three Symphonic Preludes.[7]

She found success in 1947 with a cantata setting Arthur Rimbaud's poem Ô saisons, Ô châteaux. The BBC refused to perform it at the time because the soprano range was thought to go beyond the bounds of the possible, but the BBC was nevertheless the organisation that gave first performances to many of her works from the 1940s to the 1950s. Her work in this period included incidental music for a number of poetry readings, such as Esmé Hooton's Zoo in 1956.[8] The BBC began playing her music again when her friend William Glock became Director of Music. Lutyens is remembered for her intolerance of her better-known contemporaries among English composers including Vaughan Williams, Holst, Ireland and Bax.[9] She dismissed them as "the cowpat school" in a lecture she gave at the Dartington International Summer School in the 1950s, disparaging their "folky‐wolky melodies on the cor anglais".[9]

Edward Clark had resigned from the BBC in 1936 amid much ill-feeling. He was still doing contract work for the BBC as well as freelance conducting, but those opportunities dried up and he was essentially unemployed from 1939 until his death in 1962. He was involved with the ISCM and other contemporary music promotional organisations, but always in an unpaid capacity. Lutyens paid the bills by composing film scores for Hammer's horror movies and also for their rivals Amicus Productions. She was the first female British composer to score a feature film, her first foray into the genre being Penny and the Pownall Case (1948).[10] Her other scores included Never Take Sweets from a Stranger (1960), Don't Bother to Knock (1961), Paranoiac (1963), Dr. Terror's House of Horrors (1965), The Earth Dies Screaming (1965), The Skull (1965) (a suite from this was issued on CD in 2004), Spaceflight IC-1 (1965), The Psychopath (1966), Theatre of Death (1967) and The Terrornauts (1967). Lutyens did not regard her film scores as highly as her concert works, but she still relished being referred to as the "Horror Queen", which went well with the green nail polish she habitually wore.[11] She also wrote music for many documentary films and for BBC radio and TV programmes, as well as incidental music for the stage.[1]

By the late 1960s her music was in greater favour and she received a number of important commissions, including Quincunx for orchestra with soprano and baritone soloists (1959–60), which was premiered at the 1962 Cheltenham Music Festival and uses a quartet of Wagner tubas in the orchestra. The work was well received and recorded at the time, but didn't receive a live performance in London until 1999.[12] Her Symphonies for solo piano, wind, harps and percussion was a commission for the 1961 Promenade Concerts. In 1969 she was made a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE). And Suddenly It’s Evening (1966) for tenor and ensemble, setting a translation of words by Salvatore Quasimodo, was commissioned by the BBC in 1967 and performed at the Proms in 1967, 1974 and 1976.[12]

Writing

editHer autobiography A Goldfish Bowl, describing life as a female musician in London, was published in 1972. She once said that she hated writing the book and only did so to record her husband Edward Clark's earlier achievements.[13]

Death

editElisabeth Lutyens died in London in 1983, aged 76.[14]

Selected list of works

editSee also List of compositions by Elisabeth Lutyens.

Chamber music

edit- String Quartet I, Op. 5, No. 1 (1937) – withdrawn

- String Quartet II, Op. 5, No. 5 (1938)

- String Trio, Op. 5, No. 6 (1939)

- Chamber Concerto I, Op. 8, No. 1, for 9 instruments (1939–40)

- String Quartet III, Op. 18 (1949)

- Concertante for five players, Op. 22 (1950)

- String Quartet VI, Op. 25 (1952)

- Valediction, for clarinet and piano, Op. 28 (1953–54) – dedicated to the memory of Dylan Thomas

- Capriccii, for 2 harps and percussion, Op. 33 (1955)

- Six Tempi, for 10 instruments, Op. 42 (1957)

- Wind Quintet, Op. 45 (1960)

- String Quintet, Op. 51 (1963)

- Wind Trio, Op. 52 (1963)

- String Trio, Op. 57 (1963)

- Music for Wind, for double wind quintet, Op. 60 (1963)

- Oboe Quartet: Driving out the Death, Op. 81 (1971)

- Plenum II, for oboe and 13 instruments, Op. 92 (1973)

- Plenum III, for string quartet, Op. 93 (1973)

- Clarinet Trio, Op. 135 (1979)

Vocal and choral

edit- Ô saisons, Ô châteaux! – cantata after Rimbaud, Op. 13 (1946)

- Requiem for the Living, for soli, chorus and orchestra, Op. 16 (1948)

- Stevie Smith Songs, for voice and piano (1948–53)

- Motet: Excerpta Tractatus-logico-philosophicus, for unaccompanied chorus, Op. 27 (1951) – text by Ludwig Wittgenstein

- Nativity, for soprano and organ (1951)

- De Amore for soli, chorus and orchestra, Op. 39 (1957) – text by Geoffrey Chaucer

- Quincuncx, see full orchestra

- Motet: The Country of the Stars, Op. 50 (1963) – text by Boethius translated Chaucer

- Magnificat and Nunc Dimittis (SATB), Op. ?? (February 1965)

- The Valley of Hatsu-Se, for soprano, flute, clarinet, cello and piano, Op. 62 (1965) – on early Japanese poetry

- And Suddenly It's Evening, for tenor and 11 Instruments, Op. 66 (1965) – text by Salvatore Quasimodo

- Epithalamion, for soprano and organ, Op. 67 No.3 (1968)

- Essence of Our Happinesses, for tenor, chorus and orchestra, Op. 69 (1968) – texts by Abu Yasid, John Donne and Rimbaud

- In the Direction of the Beginning, for bass and piano, Op. 76 (1970) – text by Dylan Thomas

- Anerca, for speaker, 10 guitars and percussion, Op. 77 (1970) – on Eskimo poetry

- Requiescat, for soprano and string trio, in memoriam Igor Stravinsky (1971) – text by William Blake

- Voice of Quiet Waters, for chorus and orchestra, Op. 84 (1972)

Solo instrumental

edit- 5 Intermezzi, for piano, Op. 9 (1941–42)

- Suite for organ, Op. 17 (1948)

- Holiday Diary, for piano (1949)

- Sinfonia for organ, Op. 32 (1955)

- Piano e Forte, for piano, Op. 43 (1958)

- Five Bagatelles, for piano, Op. 49 (1962)

- Helix, for piano, Op. 68 (1967)

- The Dying of the Sun, for guitar, Op. 73 (1969)

- Plenum I, for piano, Op. 87 (1972)

- Temenos, for organ, Op. 72 (1972)

- Plenum IV, for two organs, Op. 100 (1975)

- Five Impromptus, for piano, Op. 116 (1977)

- Seven Preludes, for piano, Op. 126 (1978)

- The Great Seas, for piano, Op. 132 (1979)

- Bagatelles, Books 1, 2 and 3 for piano, Op. 141 (1979)

- La natura dell'Acqua, for piano, Op. 154 (1981)

- Echo of the Wind, for solo viola, Op. 157

- ‘’Encore-Maybe’’, for piano, Op. 159

Small orchestra

edit- Chamber Concerto II, for clarinet, tenor sax, piano and strings, Op. 8, No. 2 (1940)

- Chamber Concerto III, for bassoon and small orchestra, Op. 8, No. 3 (1945)

- Chamber Concerto IV, for horn and small orchestra, Op. 8, No. 4 (1946)

- Chamber Concerto V, for string quartet and chamber orchestra, Op. 8, No. 5 (1946)

- Chamber Concerto VI (1948) was withdrawn

- Six Bagatelles, Op. 113, for six woodwind, four brass, percussion, harp, piano (doubling celeste) & five solo strings (1976)

Orchestral

edit- Three Pieces, Op. 7 (1939)

- Three Symphonic Preludes (1942)

- Viola Concerto, Op. 15 (1947)

- Music for Orchestra I, Op. 31 (1955)

- Chorale for Orchestra: Hommage a Igor Stravinsky, Op. 36

- Quincunx, for orchestra with soprano and baritone soli in one movement, Op. 44 (1959–60) – text by Sir Thomas Browne

- Music for Piano and Orchestra, Op. 59 (1963)

- Novenaria, Op. 67, No. 1 (1967)

Opera and music theatre

edit- Infidelio – seven scenes for soprano and tenor, Op. 29 (1954)

- The Numbered – opera in a Prologue and four acts after Elias Canetti, Op. 63 (1965–67)

- Time Off? Not the Ghost of a Chance! – charade in four scenes, Op. 68 (1967–68)

- Isis and Osiris – lyric drama after Plutarch, Op. 74 (1969)

- The Linnet from the Leaf – music-theatre for singers and two instrumental groups, Op. 89 (1972)

- The Waiting Game – scenes for mezzo, baritone, actor and small orchestra, Op. 91 (1973)

References

edit- ^ a b c d e Dalton, James. "Lutyens, (Agnes) Elisabeth (1906–1983), composer", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004. Retrieved 8 September 2020 (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- ^ Elisabeth Lutyens by Annika Forkert, accessed 19 December 2021

- ^ a b "Composer Elisabeth Lutyens, daughter of Edwin". The Lutyens Trust. Retrieved 8 June 2022.

- ^ Elisabeth Lutyens profile; accessed 19 December 2021.

- ^ London School of Economics and Political Science. "The Suffrage Interviews". London School of Economics and Political Science. Retrieved 5 September 2024.

- ^ Lloyd, Stephen (27 July 2001). William Walton: Muse of Fire. Boydell Press. p. 263. ISBN 9780851158037. Retrieved 27 July 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ Playback, The Bulletin of the National Sound Archive, Summer 1998 Archived 20 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine Bl.uk

- ^ "Zoo". Radio Times. No. 1679. BBC. January 1956. Retrieved 20 November 2020.

- ^ a b "cowpat music", Concise Oxford Dictionary of Music, Oxford University Press. Retrieved 8 September 2020 (subscription required)

- ^ Huckvale, p. 54

- ^ Huckvale, p. 5

- ^ a b Simeone, Nigel. Notes to Resonance CD RES10291 (2021)

- ^ Blume, Mary (5 November 1999). A French Affair: The Paris Beat, 1965-1998. Simon and Schuster. p. 179. ISBN 9781439136386. Retrieved 27 July 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Miss Elisabeth Lutyens", The Times, 15 April 1983, p. 12

Sources

edit- David Huckvale, Hammer Film Scores and the Musical Avant-Garde

Further reading

edit- Fockert, Annika (2104), Elisabeth Lutyens, MUGI online

- Fuller, Sophie (1994). The Pandora guide to women composers : Britain and the United States 1629 – present. London [u.a.]: Pandora. ISBN 0044408978. Retrieved 25 March 2017.

- Harries, Meirion and Susie, A Pilgrim Soul. The Life and work of Elisabeth Lutyens*Kenyon, Nicholas (2002). Musical lives. Oxford [u.a.]: Oxford Univ. Press. ISBN 0198605285. OCLC 50525691.

- Lutyens, Elizabeth, A Goldfish Bowl.

- Mathias, Rhiannon, Lutyens, Maconchy, Williams and Twentieth-Century British Music: A Blest Trio of Sirens (Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate, 2012); ISBN 9780754650195.

- Anthony Payne: 'Lutyens's Solution to Serial Problems', The Listener, 5 December 1963, p. 961

- Payne, Anthony; Calam, Toni (2001). "Lutyens, (Agnes) Elisabeth". Grove Music Online. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.17227. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0. (subscription or UK public library membership required)