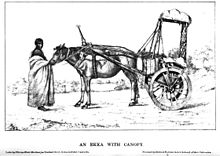

An ekka (sometimes spelt hecca,[1] ecka[2] or ekkha[3]) is a one-horse carriage used in northern India. Ekkas (the word is derived from Hindi ek for "one"[2]) were something like 'traps' (of 'a pony and trap'), and were commonly used as cabs, or private hire vehicles in 19th-century India. They find frequent mention in colonial literature of the period (for example, Kipling's "The Three Musketeers"). It is also said that some kind of ekkas were used by people of Indus Valley civilisation (without the spoked wheel).

Ekkas were typically drawn by a single horse, pony, mule (or sometimes bullock) and had a pair of large wooden wheels (and traditionally, a wooden axle[1]) and the carriage had a flat floor with a canopy providing shade to the passengers and the driver.[4] Traditionally, they lacked springs and seats, with the passengers having to sit on their haunches and withstand the jolts transmitted by the wheels. John Lockwood Kipling, artist and father of Rudyard Kipling, described the ekka as a "tea-tray on wheels" with the passengers sitting like "compressed capital N's". Bells were attached to the cart so as to warn people to stay out of the way of the cart.[5] The space below the carriage and between the wheels was available for baggage.[6][7] Wider versions with two bullocks have also been referred to as ekkas although larger two horse carriages with better seating are known as tongas.[8][9]

References

edit- ^ a b Stratton, Ezra M. (1878). The World on Wheels; or Carriages with their historical associations from the earliest to the present time. New York: Self-published. p. 203.

- ^ a b Yule, H.; A. C. Burnell (1903). Crooke, William (ed.). Hobson-Jobson (2nd ed.). London: John Murray. p. 336.

- ^ Devereaux, Captain Venus in India. London: Sphere, 1969; pp. 125-36

- ^ Sarkar, Benoy Kumar (1925). Inland transport and communication in medieval India. Calcutta University Press. pp. 22–23.

- ^ Kipling, John Lockwood (1904). Beast and Man in India. London: Macmillan and Co. pp. 190–193.

- ^ Gilbert, William H. Jr. (1944). Peoples of India. Washington: Smithsonian Institution. p. 21.

- ^ Austin, O. P. (1907). "Queer methods of travel in curious corners of the world". National Geographic Magazine. 18 (11): 687–714.

- ^ Forbes-Lindsay, C. H. (1903). India. Past and Present. Volume 2. Philadelphia: Henry L. Coates & Co. p. 98.

- ^ Randhawa, M. S. A History of Agriculture in India. Volume 3: 1757-1947. New Delhi: Indian Council of Agricultural Research. pp. 203, 205.