Edward Joris (1876–1957) was a Belgian Flemish anarchist who was involved in the 1905 bombing in Constantinople known as the Yıldız assassination attempt, which was directed against the Sultan Abdul Hamid II as a retribution for the Hamidian massacres.[1]

Edward Joris | |

|---|---|

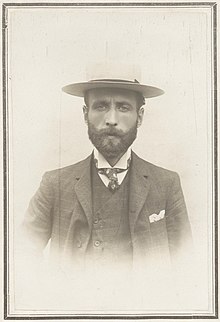

Edward Joris en 1905. | |

Through his anarchism, he took an interest in anticolonialism and became involved in the attempt after meeting two leaders of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF), Vramshabouh Kendirian and one of the founders of the organization, Christapor Mikaelian.[2]

He was sentenced to death, which triggered a significant protest movement in Belgium, involving both the Walloons and the Flemish, drawing comparisons to the Dreyfus Affair in France, with numerous political interventions advocating for his release.[3] Supporters of his release were referred to as "Jorisards" and, while connected to the French Dreyfusards, they managed to secure his release by exerting pressure on both French and Belgian authorities.[3]

Edward Joris was sent back to Belgium a few years later. He died in 1957 in Antwerp.[2]

Biography

editYouth and move into the Ottoman Empire

editBorn in 1876, Joris lost his father when he was 4 years old.[2]

He left school at 13 and worked as a shipping clerk. Engaging in left-wing politics, he was secretary of his local branch of the Belgian Workers' Party from 1895 to 1898, as well as for a trade union. He contributed to the anarchist newspaper Ontwaking under the pseudonym Edward Greene and defended an anarcho-syndicalist stance in his publications.[2]

In 1901 he travelled to Constantinople, where he was briefly employed writing commercial correspondence in French and English and then found work at the Singer sewing machine company. In 1902 his fiancée, Anna Nellens, joined him in Istanbul and they got married, even if he seemed to have been somewhat reluctant to do so.[2]

On August 14, 1902, he was dismissed by his employer and found employment again by the end of the year 1902 in a sewing company in Constantinople.[2]

Mosque Yıldız Attack

editThe connections between anarchists and the Armenian national liberation movement were established in the 1890s, notably with Alexander Atabekian. In 1904, during an annual congress bringing together Armenian and Bulgarian representatives, the Armenian Revolutionary Federation decided to assassinate Sultan Abdul Hamid II in response to the Hamidian massacres.[2] One of the French anarchist representatives sensitized to the Armenian issue, Pierre Quillard, attended the congress and reported to his anarchist colleagues that the Armenians intended to use 'extreme methods.'[4] Edward Joris later said that it was the reading of Quillard's journal, Pro Armenia, that motivated his choice to support the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF).[2]

In this context, Joris met a colleague named Vramshabouh Kendirian, nicknamed Vram. Vram introduced him to one of the leaders of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF), Christapor Mikaelian, representing the Marxist branch of the ARF.[2] He sheltered two conspirators in his home, and his house served as a meeting place for discussions and storage of explosives and firearms. Both Vramshabouh Kendirian and Christapor Mikaelian die in 1905 in Sofia, Bulgaria, while experimenting with explosive devices.[2]

His passport was found on Kendirian's body, and Joris expressed deep sorrow over Kendirian's death, referring to him as a "very good friend." In total, 39 individuals were involved in the plot, including his wife, Anna Nellens, and the self-proclaimed daughter of Christapor Mikaelian, Nadedja Datalian.[2]

Joris enabled the organization to bypass customs, allowing the cart carrying the explosives to pass through, coming from Vienna.[5] The explosives, consisting of 140 kilograms of picric acid, were conveyed by Bulgarian sailors.[2]

The bombing was carried out on 21 July 1905, killing 26 and injuring 58 but failing to harm the sultan himself. Joris was arrested six days later. He was brought to trial on 25 November and sentenced to death on 18 December. Due to diplomatic pressure from Belgium, the sentence was never carried out.[2][6] His wife was also sentenced to death, but in absentia, as she managed to escape before being apprehended by the Ottoman police. He spoke during his trial and declared:[2]

About a year before the attempt I read a manifest in the Parisian paper Pro Armenia for the poor Armenians. This made a deep impression on me. It was my duty to make myself available to the Armenian committee. That is how I came to Constantinople.

Contestation, Jorisards and freedom

editWhile he was imprisoned, awaiting his execution, a significant protest movement emerged in Belgium to support him.[3] Its members, referred to as the "Jorisards," demanded his immediate release and were likened to the Dreyfusards of Belgium by historians.[3][7] They received support from notable Dreyfusards, such as Georges Clemenceau, who published a letter from one of their leaders, Georges Lorand, a progressive Walloon deputy and leader of the Jorisards, in L'Aurore.[3] The Human Rights League in France also demonstrated for Edward Joris' release.[3] The movement quickly extended beyond the anarchist circle of Antwerp and spread throughout Belgian society, particularly among intellectual socialist and left-leaning elites, uniting both Walloons and Flemish.[3] On June 22, 1907, in Les Temps Nouveaux, a French anarchist journal, Jean Grave and Segher Rabaud published two statements of support for Edward Joris. In these, they declared, among other things:[8]

Our comrades remember Joris, accused in the plot against the Yldiz-Kiosk bandit, sentenced to death by the judges of the massacrer a year and a half ago. [...] The Armenians are arrested en masse, and Joris, the dangerous and terrible one, who from the depths of his cell makes the bombs dance, will suffer from closer surveillance due to the dirty exploits of the police scum.

Due to diplomatic pressure from Belgium and France, the sentence was not carried out. A support committee was established by left-wing intellectuals in Belgium to maintain pressure on the Belgian government to work towards his release. Joris was kept in prison until 23 December 1907 and then returned to Belgium.[2] His letters from prison formed the basis of a later book about his involvement in the plot.[9]

After his return to Belgium, Joris worked as a bookseller and was secretary to the Antwerp branch of the Ligue des droits de l'homme.[10] After the First World War he was convicted of supporting the occupying forces' Flamenpolitik, and sought refuge in the Netherlands. He returned to Belgium after an amnesty in 1929 and worked as a self-employed publicity agent. He died in 1957.[2]

Anarchism and the Armenian national movement

editThe proximity between an anarchist internationalist and the Armenian national movement has been questioned, but Maarten Van Ginderachter believes that during that time, anarchist figures like Bakunin or Proudhon were open to supporting small anti-colonial national movements, such as the demands of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation:

Joris’s best friend Resseler explicitly mentioned Armenia in September 1901 as one example of bourgeois-capitalist violence toward the working class in a longer list: ‘Our whole bourgeois society is based on violence: all governments burn and kill in the Transvaal, in China, in the Congo, on Java, in Cuba and on the Philippines, in Armenia’. This was a clear example of the emphatic anarchist interest in anti-imperialism and anticolonialism.

From this synopsis it is important to remember that there is no necessary theoretical or practical contradiction between socialism (be it anarchist or reformist), nationalism (be it cultural or political) and internationalism. In general, anarchists were more drawn to anticolonial struggles in the Third World than Marxists. We do know from contemporary sources that Joris held radically internationalist, cosmopolitan ideas, in favor of ‘worldly solidarity’ and ‘humanity’. Recounting the court proceedings to his wife in an undated letter from his Istanbul prison, he claimed to have said in court: ‘The whole Universe is my fatherland, the whole of humanity is my family and all those who suffer are my brothers. I do not recognize any borders.' At the same time, however, Joris clearly believed in the existence of separate peoples that had distinct national qualities. His writings on Armenia are a case in point.[2]

References

edit- ^ Gaïdz Minassian, "The Armenian Revolutionary Federation and Operation 'Nejuik'", in To Kill a Sultan: A Transnational History of the Attempt on Abdülhamid II (1905), edited by Houssine Alloul, Edhem Eldem and Henk de Smaele (Palgrave Macmillan, 2018), p. 53.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Maarten Van Ginderachter, "Edward Joris: Caught between Continents and Ideologies?" in To Kill a Sultan: A Transnational History of the Attempt on Abdülhamid II (1905), edited by Houssine Alloul, Edhem Eldem and Henk de Smaele (Palgrave Macmillan, 2018), pp. 67-98.

- ^ a b c d e f g Beyen, Marnix (2018), Alloul, Houssine; Eldem, Edhem; de Smaele, Henk (eds.), "The 'Jorisards': Public Mobilization Between Local Emotions and Universal Rights", To Kill a Sultan: A Transnational History of the Attempt on Abdülhamid II (1905), London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, pp. 225–246, doi:10.1057/978-1-137-48932-6_8, ISBN 978-1-137-48932-6, retrieved 2023-08-15

- ^ "Les Temps nouveaux". Gallica. 1905-12-09. Retrieved 2023-11-16.

- ^ Çağlar, Burhan; Can, Ömer Faruk; Kılıçarslan, Hacer (2021-03-01). Living in the Ottoman Lands: Identities Administration and Warfare. Kronik.

- ^ Richard Bach Jensen, The Battle against Anarchist Terrorism: An International History, 1878–1934 (Cambridge University Press, 2014), p. 307.

- ^ Christophe Verbruggen, Schrijverschap in de Belgische belle époque: een sociaal-culturele geschiedenis (Ghent and Nijmegen, 2009), pp. 161-166.

- ^ "Les Temps nouveaux". Gallica. 1907-06-22. Retrieved 2023-11-16.

- ^ Walter Resseler and Benoit Suykerbuyk, Dynamiet voor de sultan: Carolus Edward Joris in Konstantinopel (Antwerp, b+b, 1997).

- ^ De Ligue Belge des Droits de l’Homme (1901-1939), Joost Depotter https://libstore.ugent.be/fulltxt/RUG01/002/162/503/RUG01-002162503_2014_0001_AC.pdf