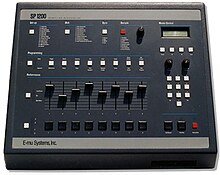

The E-mu SP-1200 is a sampling drum machine designed by Dave Rossum and released in August 1987 by E-mu Systems. Like its predecessor, the SP-12, it was designed as a drum machine featuring user sampling. The distinctive character of its sound, often described as "warm," "dirty," and "gritty," and attributed to SP-1200's low 26.04 kHz sampling rate, 12-bit sampling resolution, drop-sample pitch-shifting, and analog SSM2044 filter chips (ICs), has sustained demand for the SP-1200 more than thirty-five years after its debut, despite the availability of digital audio workstations and samplers/sequencers with superior technical specifications.

| SP-1200 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Manufacturer | E-mu Systems[1] Rossum Electro-Music (2021 reissue)[2][3][4] |

| Dates | 1987–1990, 1993-1998,[1][5][6][7] 2021–present[2][3][4] |

| Price | US $2,995 (1987)[6] US $3,999 (2021 reissue)[4][8] |

| Technical specifications | |

| Polyphony | polyphonic 8 voices[6] |

| Timbrality | Fully multi-timbral[6] |

| Synthesis type | 26.04 kHz 12-bit samples,[6] drop-sample pitch-shifting[9][10][11] |

| Filter | SSM2044,[5] SSI2144 (2021 reissue)[2][4] |

| Storage memory | 10 seconds sample time, 100 user patterns, 100 user songs,[6] 20 seconds sample time (2021 reissue)[2][4][8] |

| Effects | Independent level and tuning for all sounds[6] |

| Input/output | |

| Keyboard | 8 hard plastic touch-sensitive buttons[5][6] |

| External control | MIDI, SMPTE[5][6] |

The SP-1200 is associated with the golden age of hip hop. It enabled musicians to construct the bulk of a song within one piece of portable gear, a first for the industry, reducing production costs and increasing creative control for hip-hop artists. According to the Village Voice, "The machine rose to such prominence that its strengths and weaknesses sculpted an entire era of music: the crunchy digitized drums, choppy segmented samples, and murky filtered basslines that characterize the vintage New York sound are all mechanisms of the machine."

History and development

editE-mu Systems began as a manufacturer of analog modular synthesizers 1971 and pioneered applications of digital technology in electronic musical instruments including a digital sequencer and the first digital polyphonic keyboard.[5] E-mu supplemented income from modular synthesizers with royalties from the first ever analog chips (ICs) for analog synthesizers, created by Dave Rossum with Ron Dow and manufactured by Solid State Music (SSM), and by licensing and consulting for Linn, Oberheim, and Sequential.[5][9] E-mu first used the Zilog Z80 microprocessor in the 4060 Programmable Polyphonic Keyboard and Sequencer released in 1977 and continued to use Z80 processors in many of its designs through SP1200 in 1987.[1][5][6][12][13] Roger Linn hired Dave Rossum to review the electrical design of Linn LM-1, the first digital drum machine.[6][9] Precipitated by Sequential redesigning the Prophet 5 Rev 3 to use Curtis (CEM) chips (ICs) and no longer paying royalties to E-mu (for the earlier design using SSM chips), E-mu pivoted in 1980 from designing analog synthesizers to digital sampling technology and released the original Emulator sampling synthesizer in 1981.[5]

Just as engineering a digital sampler to operate using one shared memory had allowed Emulator to be made more attainable than systems including the Fairlight CMI, E-mu Systems co-founders Scott Wedge and Dave Rossum realized that an affordable digital drum machine could be invented using a shared memory, resulting in Drumulator, the first programmable digital drum machine priced under $1000, significantly below the LM-1 and Linndrum.[5][14] As a compromise between bandwidth and sampling time, the low 26.04 kHz sample rate was chosen early on.[5][6][15][16] A major success, Drumulator sold over 10,000 units from 1983 to 1985 and saw E-mu grow to a medium-sized company.[5][14]

After Emulator II in 1984, E-mu decided to pursue a drum machine to follow-up Drumulator, which would eventually become SP-12 and SP-1200. Design was led by Dave Rossum's electronic engineering, with functional design contributions from Marco Alpert (who would together go on to co-found Rossum Electro-Music, also known as "Rossum.")[5][10][14] Work began with modifications to existing Drumulator microcode by new engineer Donna Murray allowing pitch shifting (tuning) of sounds. Though the drop-sample interpolation introduced a lot of distortion, musicians at E-mu thought it musically useful. E-mu especially sought to apply their Emulator experience to add a drum machine with user sampling features to the successful Drumulator product line.[5][6][9][10][11][17] Scott Wedge invented a technology enabling dynamics to be performed using a piezo sensor on the circuit board listening for the button's impact.[5][6][13][18]

SP-12 was the first sampling drum machine released.[6] The main changes from Drumulator to SP-12 were the introduction of integrated 12-bit linear user sampling allowing users to record their own sounds and improvements to the user interface, while the playback electronics remained mostly unchanged.[1][5][6][12][14][17] E-mu SP-12 was initially advertised as “Drumulator II” by E-mu Systems at the NAMM Winter Music & Sound Market and Musikmesse Frankfurt in February of 1985 before its official launch that summer at the NAMM International Music & Sound Expo.[5][14][17][19][20] “SP” is an initialism for “Sampling Percussion,” and 12 is a reference to its 12-bit linear data format.[21] At $2745, SP-12 remained a more attainable sampling drum machine as compared to the Linn 9000, which started at $5000 (not including the sampling add-in-card released later), and the Studio 440 from Sequential when it was released in 1986, also priced at $5000.[5][6][22][23]

In contrast to implementing unique sound engines for each of its other samplers so far, beginning with Emulator and Emulator II, and growing in ambition and scope with purpose-built ICs designed by Dave Rossum, including E-chip powering Emax (1986) and F-chips used in Emulator III (1987), SP-1200's short and low-risk development updated the SP-12 sampling drum machine with more sampling time and an integrated disk drive, with E-mu reusing the sample playback engine used in SP-12 and in Drumulator since 1983.[5][6] SP-1200 would become both the last E-mu sampler to not integrate custom E-mu chips (ICs) and the last to include analog SSM chips, using SSM2044 in its dynamic filters until they became unavailable in 1998.[5][6] E-mu Systems updated SP-12 with improvements and a "Turbo" option expanding the total available sample time to 5 seconds before it was eventually replaced in the product line when SP-1200 was released in August 1987.[1][5][6][12] Combined with 10 seconds of user sampling time, SP-1200's $2995 price provided artists with a practical entrypoint to sample-based music production.[6]

Differences from the SP-12

editThe SP-1200 retained the capabilities, inputs and outputs of its predecessor, the SP-12, minus the cassette output and connectivity for the 1541 Commodore Computer 5.25" floppy disk drive.[6] In their place, the SP-1200 uses an integrated disk drive for storing and loading sounds and sequences, making it particularly attractive to producers.[5][6][9]

Unlike the SP-12 and Drumulator, the SP-1200 does not use any ROM-based samples; all samples are stored in volatile RAM and loaded from 3.5" disk.[3][5][6][24] Maximum sampling time was doubled from the upgraded SP-12 Turbo, to 10 seconds, though the maximum duration of an individual sound remained limited to 2.5 seconds.[3][5][6][7][25]

SP-1200 provides additional unfiltered versions of the signals from its first six channels (not available on SP-12) using TRS connections for each individual output, providing the option to use unfiltered signals from all eight channels / voices alternatively to their analog filters.[6][13][15][25][26]

Features

editThe SP-1200 can store up to 100 patterns, 100 songs, and has a 5,000-note maximum memory for sequences.[6] The sequencer enables musicians to create patterns using both step programming and real-time recording using the touch-sensitive[5][6] front panel buttons (and via external MIDI note input). Patterns can be organized into songs, and swing, quantization, and tempo and mix changes can be applied. SP-1200 can both generate SMPTE, MIDI, and analog clock signals and synchronize its tempo and sequencer to them. Users can also tap the front panel Tap / Repeat button or an external footswitch to program the tempo.[27][unreliable source?][13]

Selecting between banks A, B, C, and D gives access to each of the 32 sounds. Eight sliders are used to set sounds' pitch and volume parameters. Large buttons below each slider are used to select or play sounds with dynamics using a piezo sensor mounted on the circuit board.[5][6][13]

Sound

editThe distinctive character of SP-1200's sound is often described as "warm," "dirty," and "gritty."[2][5][6][7][9][25][28] The sound is attributed to SP-1200's low 26.04 kHz sampling rate[15] and 12-bit linear sampling resolution. SP-1200 is known for the character of its drop-sample pitch-shifting.[9][10][11] The analog SSM2044 filter chips (ICs) contribute to the timbre of E-mu's drum machines.[3][5][6][7] The characteristic sound has sustained demand for the SP-1200 more than thirty-five years after its debut, despite the availability of digital audio workstations and samplers/sequencers with superior technical specifications.[3][5][6][29][30][31]

SP-1200 uses a 12-bit linear data format and the same 26.04kHz sample rate E-mu previously used in Drumulator and SP-12.[5][6][8][13][16][26] The sample rate was chosen early on in Drumulator’s development as a compromise between bandwidth and sampling time.[5][6][15] A reconstruction filter was deliberately omitted, resulting in a brighter sound due to imaging (sounds above the Nyquist frequency).[6][13][26][15] SP-12, and SP-1200 instead feature three pairs of analog lowpass filters at successively higher frequencies, including two dynamic SSM2044 filters on channels 1 and 2, while channels 7 and 8 are unfiltered entirely.[5][6][9][15][13][26]

SP-1200 uses drop-sample pitch-shifting (simply dropping or replaying sample data in order to pitch/speed the playback up or down), producing significant additional (unfiltered) audible artifacts and distortion which proved to be musical useful.[6][15] More advanced pitch-shifting algorithms like linear and higher-order interpolation reproduce high frequency data more accurately, but consequently may not sound as "warm" in comparison to simpler techniques.[9][10][11]

Technique

editUpon its release, hip-hop producers embraced sampling loops and musical phrases such as breaks in addition to individual drum sounds with SP-1200.[3][6][29][30][24][32] Early adopters soon innovated with techniques beyond looping by combining SP-1200's truncation and sequencing features to slice (or "chop") samples of drums and other instruments into shorter pieces and re-compose them to create original productions.[3][6][25][31][33][34]

Music producers discovered and shared techniques using SP-1200's tuning (pitch) features to enable samples longer than 2.5 seconds, and more than 10 seconds total sampling time, to be used. Using a tape machine, another sampler, or, most famously, a vinyl turntable with multiple and/or variable playback speeds, sounds can be pitched up (sped up), allowing them to be sampled with SP-1200 using less sampling time (RAM). SP-1200 can shift the pitch of the sounds down to the original pitch (and beyond) when they are played back. The prevalent technique compresses samples of longer durations into the available memory, while reducing their fidelity and introducing notably more audible artifacts.[6][25]

Longevity and reissue

editE-mu and Rossum Samplers and Drum Machines | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

1980 — – 1982 — – 1984 — – 1986 — – 1988 — – 1990 — – 1992 — – 1994 — – 1996 — – 1998 — – 2000 — – 2002 — – 2004 — – 2006 — – 2008 — – 2010 — – 2012 — – 2014 — – 2016 — – 2018 — – 2020 — – 2022 — – 2024 — – | Assimil8or[43] ESI[5] |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

SP-1200 enabled musicians to construct the bulk of a song within one piece of portable gear, a first for the industry.[1][3][24] This reduced production costs while increasing creative control for hip-hop artists.[3][33] The SP-1200 became associated with the golden age of hip hop.[1][3][6][7][25] According to the Village Voice, "The machine rose to such prominence that its strengths and weaknesses sculpted an entire era of music: the crunchy digitized drums, choppy segmented samples, and murky filtered basslines that characterize the vintage New York sound are all mechanisms of the machine."[25]

E-mu Systems's sampling drum machines had earned a strong following, especially from hip hop music producers seeking out its characteristic sound, by the time of SP-1200's initial discontinuation in 1990.[3][5][6][24] Owing to unending demand, SP-1200 was reissued by E-mu in 1993 with a cooler-running power supply and black chassis that complied with contemporaneous electrical regulations, and became E-mu's longest-lived product in 1996.[3][5][6] E-mu continued to build SP-1200 units until the unavailability of aging parts including the analog SSM2044 filter chips (ICs), forced the instrument's second discontinuation, marked by a "Final Edition" of SP-1200 units, in 1998.[2][5][6]

In 2015, E-mu Systems co-founder and original SP-12 and SP-1200 designer Dave Rossum returned to designing synthesizers, co-founding a new company, Rossum Electro-Music ("Rossum") that soon began receiving requests for SP-1200.[3][10] Sound Semiconductor's announcement of SSI2144, an analog filter chip (IC) using a modern manufacturing process with the same internal circuit and sonic character as the SSM2044 (also designed by Dave Rossum),[44][45] and Rossum's announcement of Assimil8or, a new hardware sampler in eurorack format in 2017,[43] further fueled speculation of a new SP-1200 product. Rossum announced an extremely limited 35th Anniversary edition of rebuilt SP-1200 units in 2020.[46][47]

In November 2021, Rossum announced a reissue of the SP-1200.[2][3][4] The Rossum SP-1200 provides 20 seconds total sampling time, equal to twice the original SP-1200's 10 seconds.[2][4][47] A new SD card interface replaces the 3.5" disk drive.[2][3][4][47] The chassis is made entirely from metal to comply with modern emissions standards.[47] The unavailable SSM2044 filters are replaced with functionally identical SSM2144 filter chips (IC).[2][4]

Notable works

edit1988

editPublic Enemy - It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back (Def Jam, June 28, 1988)

- Produced by Chuck D, Rick Rubin, and Hank Shocklee[49]

N.W.A. - Straight Outta Compton (Ruthless, August 8, 1988)

Ultramagnetic MCs - Critical Beatdown (Next Plateau, October 4, 1988)

- Produced by Andre Harrell (exec.), Ultramagnetic MCs, Paul C, Ced-Gee[29]

1989

editBig Daddy Kane - It's a Big Daddy Thing (Cold Chillin', September 19, 1989)

- "Another Victory" and "Calling Mr. Welfare" (featuring DJ Red Alert) produced by Easy Mo Bee[31]

1990

editA Tribe Called Quest - People's Instinctive Travels and the Paths of Rhythm (Jive, April 10, 1990)[51][52]

Public Enemy - Fear of a Black Planet (Def Jam, April 10, 1990)

- Produced by The Bomb Squad[53]

1991

editA Tribe Called Quest - The Low End Theory (Jive, September 24, 1991)[52]

1992

editGang Starr - "Take it Personal" (Chrysalis, March 30, 1992)

- Produced by DJ Premier[28]

- Single from the album Daily Operation

Pete Rock & CL Smooth - "They Reminisce Over You (T.R.O.Y.)" (Elektra, April 2, 1992)

- Produced by Pete Rock[25]

- Single from the album Mecca and the Soul Brother

Miles Davis - Doo-Bop (Rhino, Jun 30, 1992)

- Produced by Easy Mo Bee[31][54]

1993

editA Tribe Called Quest - Midnight Marauders (Jive, November 9, 1993)[52]

Wu-Tang Clan - Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers) (Loud, November 9, 1993)

1994

editCraig Mack - "Flava in Ya Ear" (Bad Boy, July 26, 1994)

- Produced by Easy Mo Bee[31]

The Notorious B.I.G. - Ready to Die (Bad Boy, September 13, 1994)

- "Gimme the Loot", "Machine Gun Funk", "Warning", "Ready to Die", "The What" (featuring Method Man), and "Friend of Mine" produced by Easy Mo Bee[31]

- "Suicidal Thoughts" produced by Lord Finesse

1995

edit2Pac - Me Against the World (Interscope, March 14, 1995)

- "If I Die 2Nite" and "Temptations" produced by Easy Mo Bee[31]

The Pharcyde - Labcabincalifornia (Delicious Vinyl, November 14, 1995)

1996

editLord Finesse - The Awakening (Penalty, February 20, 1996)

1997

editDaft Punk - Homework (Virgin, January 20, 1997)[57][58]

1998

editJuvenile - "Ha" (Cash Money, October 17, 1998)

- Produced by Mannie Fresh[59]

- from the album 400 Degreez

2001

editDaft Punk - Discovery (Virgin, March 12 2001)[60]

2002

editJel - 10 Seconds (Mush, October 22, 2002)[61]

2003

editAlicia Keys - "The Diary of Alicia Keys" (J, December 2, 2003)

- "If I Was Your Woman"/"Walk on By" produced by Alicia Keys, Easy Mo Bee,[31] D'Wayne Wiggins

2012

editKid Koala - 12 Bit Blues (Ninja Tune, September 17, 2012)[62]

2014

editLord Finesse - The SP1200 Project: A Re-Awakening (Slice of Spice, July 28, 2014)

2019

editPete Rock - Return of the SP1200 (Tru Soul, April 13, 2019)

2022

editPete Rock - Return of the SP1200 V.2 (Tru Soul, Apr 23, 2022)

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Swash, Rosie (12 June 2011). "The SP-1200 sampler changes everything". The Guardian. Guardian News and Media Limited. Retrieved 16 July 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Mullen, Matt (4 November 2021). "Reissue of the classic SP-1200 sampler announced by Dave Rossum". MusicRadar. Retrieved 5 July 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Stokes, William (12 April 2022). "The E-mu SP-1200: How one sampler ushered in a revolution". MusicTech. NME. Retrieved 18 July 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Vincent, Robin (4 Nov 2021). "Rossum SP-1200: Authentic reissue of the iconic SP-1200 Sampling Drum Machine". GearNews. Retrieved 22 July 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba Keeble, Rob (September 2002). "30 Years of Emu". Sound on Sound. SOS Publications Group. Retrieved 5 July 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw Hyland, Simon (2011). SP-1200: The Art and Science. 27Sens. p. 35-37,46,55,61-63,82,86,99,116. ISBN 2953541012.

- ^ a b c d e "Nine Samplers That Defined Dance Music". Attack Magazine. Retrieved 22 July 2024.

- ^ a b c "SP-1200". Rossum Electro-Music. Archived from the original on 5 July 2024. Retrieved 5 July 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Grandl, Peter (3 July 2015). "Interview: Dave Rossum E-MU, Part Two - English Version". Amazona.de. Retrieved 30 July 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g Grandl, Peter (15 July 2015). "Interview: Dave Rossum E-mu, Part Four - English Version". Amazona.de. Retrieved 30 July 2024.

- ^ a b c d "Assimil8or Operation Manual" (PDF). Rossum Electro-Music. Rossum Electro-Music. 2018. p. 46. Retrieved 31 July 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Vail, Mark (2014). The Synthesizer. Oxford University Press. p. 73-75. ISBN 978-0195394894.

- ^ a b c d e f g h SP-1200 Sampling Percussion System Service Manual. E-mu Systems. 1987. Retrieved 5 July 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Rossum, Dave. How did Dave first get into drum machines?. Rossum Electro-Music. Retrieved 27 August 2024 – via YouTube.

- ^ a b c d e f g Rossum, Dave. Why do SP-1200 channel outputs feature different analog filters?. Rossum Electro-Music. Retrieved 5 July 2024 – via YouTube.

- ^ a b E-mu Systems Drumulator Service Manual. E-mu Systems. 1983. Retrieved 5 July 2024.

- ^ a b c Rossum, Dave. "For whom was the SP-1200 originally designed?". youtube.com. Rossum Electro-Music. Retrieved 5 July 2024.

- ^ Rossum, Dave. "How do SP-1200's dynamic play buttons work?". Rossum Electro-Music. Retrieved 28 August 2024.

- ^ Vincent, Biff (October 21, 2022). "E-mu Systems - Frankfurt Music Show 1985". youtube.com. Denise Gallant.

- ^ Wiffen, Paul (August 1985). "Way Down Yonder". Electronics & Music Maker. Retrieved 27 August 2024.

- ^ Mark Katz (2010). Capturing Sound: How Technology Has Changed Music (revised ed.). University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-26105-1.

- ^ WIffen, Paul (April 1985). "Linn 9000 Digital Drum Machine and Keyboard Recorder". mu:zines. Electronics & Music Maker. Retrieved 29 August 2024.

- ^ Henrit, Ben (April 1985). "Linn 9000 Rhythmcheck". mu:zines. International Musician & Recording World. Retrieved 29 August 2024.

- ^ a b c d "Easy Mo Bee: "If It Wasn't For Marley Marl I Wouldn't Be Making Beats"". theurbandaily.com. Interactive One, LLC. Retrieved 2024-05-27.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Detrick, Ben (6 November 2007). "The Dirty Heartbeat of the Golden Age". The Village Voice. Retrieved 2020-05-29.

- ^ a b c d Davies, Steve (1985). SP-12 Sampling Percussion System Service Manual (PDF). E-mu Systems. Retrieved 5 July 2024.

- ^ The Emulator Archive

- ^ a b DJ Premier (October 19, 2021). "So Wassup? Episode 11 Gang Starr "Take It Personal"". youtube.com. DJ Premier. Retrieved 31 July 2024.

- ^ a b c Shapiro, Peter (2003). "Ultramagnetic MCs: Critical Beatdown". In Wang, Oliver (ed.). Classic Material: The Hip-Hop Album Guide. ECW Press. ISBN 978-1-55022-561-7.

- ^ a b Shapiro, Peter (2005). The Rough Guide to Hip-Hop (2nd ed.). Rough Guides. ISBN 1-84353-263-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Maru, Sean (2008). "Vintage Series Artist Connection E-MU SP-1200 Producer Easy Moe Bee". Producer's Edge Magazine. Retrieved 19 July 2024.

- ^ Muhammad, Ali Shaheed; Kelley, Frannie (September 12, 2013). "Microphone Check: Marley Marl On The Bridge Wars, LL Cool J And Discovering Sampling". NPR. Archived from the original on August 13, 2020. Retrieved August 10, 2020.

- ^ a b Sorcinelli, Gino (3 May 2017). "Easy Mo Bee Explains How a Historic Lawsuit Made Him a Better Producer". Medium. Retrieved 19 July 2024.

- ^ Serwer, Jesse (16 October 2012). "The 77 Best Rock Samples in Rap History". Complex Network. Complex. Retrieved 19 July 2024.

- ^ Wiffen, Paul (August 1985). "Way Down Yonder". Electronics & Music Maker. Retrieved 5 July 2024.

- ^ Vincent, Biff (October 21, 2022). "E-mu Systems - Frankfurt Music Show 1985". youtube.com. Denise Gallant.

- ^ Paul Wiffen (July 1995). "Emu Systems E64". Sound on Sound. Retrieved 2024-02-24.

- ^ a b Paul Wiffen (May 1997). "Emu E4X". Sound on Sound. Retrieved 2024-02-24.

- ^ a b White, Paul. "Emu E4XT Ultra". Sound on Sound. Retrieved 27 August 2024.

- ^ a b "Emulator X Studio". Sound On Sound. June 2004. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- ^ "Emu Emulator X2". Sound On Sound. August 2006. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- ^ "E-MU Emulator X3 review". Music Radar. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016.

- ^ a b Vincent, Robin. "Superbooth 2017: Rossum Electro-Music Assimil8or Phase Modulation Sampler". Gearnews. Retrieved 24 July 2024.

- ^ a b "SSI2144 Datasheet" (PDF). Sound Semiconductor. 2017. Retrieved 24 July 2024.

- ^ a b "Prophet X uses filter from new audio chip makers". Sound On Sound. 7 June 2018. Retrieved 24 July 2024.

Both the original SSM2044 and new SSI2144 were designed by electronic music icon Dave Rossum.

- ^ a b Kirn, Peter. "If you've got $7500, you can also have an E-mu SP-1200 sampler remake". CDM. Retrieved 24 July 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Gumble, Daniel. "A Hip-Hop Legend: Everything You Need to Know About the New Rossum SP-1200". Headliner Magazine. Retrieved 24 July 2024.

- ^ "Emulator X3". Creative. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- ^ Charnas, Dan. "Respect : Making Noise". Scratch (July/August 2005): pg. 120.

- ^ Brewster, Will. "Gear Rundown: Dr. Dre". Mixdown. Mixdown Magazine. Retrieved 31 July 2024.

- ^ Coleman, Brian (June 12, 2007). Check the Technique. Villard. p. 439. ISBN 978-0-8129-7775-2.

- ^ a b c "Exclusive: Q-Tip Interview". Moovmnt.com. Retrieved 31 July 2024.

- ^ Dery, Mark (2004). "Public Enemy: Confrontation". In Forman, Murray; Neal, Mark Anthony (eds.). That's the Joint!: The Hip-Hop Studies Reader. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-96919-0.

- ^ "Doo-Bop". Miles Davis. Retrieved 31 July 2024.

- ^ England, Adam (July 27, 2023). "RZA's signed E-Mu SP-1200 sampler sells for $70,000 in auction". MusicTech. MusicTech. Retrieved 31 July 2024.

- ^ Brewster, Will (November 9, 2023). "Gear Rundown: J Dilla". Mixmag. Retrieved 31 July 2024.

- ^ Hinton, Patrick (February 23, 2021). "Here's a List of All of the Gear Daft Punk Used to Make 'Homework'". Mixmag. Retrieved 31 July 2024.

- ^ "Daft Punk's Homework Synth Sounds". ReverbMachine. Retrieved 31 July 2024.

- ^ Sorcinelli, Gino (Oct 7, 2016). "Mannie Fresh Made Juvenile's Entire "Ha" Beat With an E-mu SP-1200". Medium. Retrieved 31 July 2024.

- ^ Brunner, Vincent (2001). "Interview with Daft Punk in "Keyboards"". Retrieved 31 July 2024.

- ^ Burns, Todd (September 1, 2003). "Jel - 10 Seconds". Stylus Magazine. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved July 31, 2024.

- ^ Chick, Stevie (2012). "Kid Koala 12 Bit Blues Review". BBC iPlayer. Retrieved December 1, 2014.