The Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt (notated Dynasty XVIII, alternatively 18th Dynasty or Dynasty 18) is classified as the first dynasty of the New Kingdom of Egypt, the era in which ancient Egypt achieved the peak of its power. The Eighteenth Dynasty spanned the period from 1550/1549 to 1292 BC. This dynasty is also known as the Thutmoside Dynasty[1]: 156 ) for the four pharaohs named Thutmose.

Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 1550 BC–1292 BC | |||||||||||

The Egyptian Eighteenth Dynasty's empire at its greatest territorial extent under Thutmose III | |||||||||||

| Capital | Thebes, Akhetaten (1351–1334) BC | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Middle Egyptian (to c. 1350 BC) Late Egyptian (from c. 1350 BC) Canaanite languages Nubian languages Akkadian (diplomatic and trade language) | ||||||||||

| Religion | Ancient Egyptian religion Atenism (1351–1334) BC | ||||||||||

| Government | Absolute monarchy | ||||||||||

| Historical era | New Kingdom of Egypt | ||||||||||

• Defeat of the Fifteenth Dynasty (expulsion of the Hyksos) | c. 1550 BC | ||||||||||

| c. 1457 BC | |||||||||||

| c. 1350–1330 BC | |||||||||||

• Death of Horemheb | 1292 BC | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

Several of Egypt's most famous pharaohs were from the Eighteenth Dynasty, including Tutankhamun, whose tomb was discovered by Howard Carter in 1922. Other famous pharaohs of the dynasty include Hatshepsut (c. 1479 BC–1458 BC), the longest-reigning woman pharaoh of an indigenous dynasty, and Akhenaten (c. 1353–1336 BC), the "heretic pharaoh", with his Great Royal Wife, Nefertiti. The Eighteenth Dynasty is unique among Egyptian dynasties in that it had two queens regnant, women who ruled as sole pharaoh: Hatshepsut and Neferneferuaten, usually identified as Nefertiti.[2]

History

editEarly Dynasty XVIII

editDynasty XVIII was founded by Ahmose I, the brother or son of Kamose, the last ruler of the 17th Dynasty. Ahmose finished the campaign to expel the Hyksos rulers. His reign is seen as the end of the Second Intermediate Period and the start of the New Kingdom. Ahmose's consort, Queen Ahmose-Nefertari was "arguably the most venerated woman in Egyptian history, and the grandmother of the 18th Dynasty."[3] She was deified after she died. Ahmose was succeeded by his son, Amenhotep I, whose reign was relatively uneventful.[4]

Amenhotep I probably left no male heir and the next pharaoh, Thutmose I, seems to have been related to the royal family through marriage. During his reign, the borders of Egypt's empire reached their greatest expanse, extending in the north to Carchemish on the Euphrates and in the south up to Kanisah Kurgus beyond the fourth cataract of the Nile. Thutmose I was succeeded by Thutmose II and his queen, Hatshepsut, who was the daughter of Thutmose I. After her husband's death and a period of regency for her minor stepson (who would later become pharaoh as Thutmose III) Hatshepsut became pharaoh in her own right and ruled for over twenty years.

Thutmose III, who became known as the greatest military pharaoh ever, also had a lengthy reign after becoming pharaoh. He had a second co-regency in his old age with his son Amenhotep II. Amenhotep II was succeeded by Thutmose IV, who in his turn was followed by his son Amenhotep III, whose reign is seen as a high point in this dynasty.

Amenhotep III's reign was a period of unprecedented prosperity, artistic splendor, and international power, as attested by over 250 statues (more than any other pharaoh) and 200 large stone scarabs discovered from Syria to Nubia.[5] Amenhotep III undertook large scale building programmes, the extent of which can only be compared with those of the much longer reign of Ramesses II during Dynasty XIX.[6] Amenhotep III's consort was the Great Royal Wife Tiye, for whom he built an artificial lake, as described on eleven scarabs.[7]

Akhenaten, the Amarna Period, and Tutankhamun

edit| |

Amenhotep III may have shared the throne for up to twelve years with his son Amenhotep IV. There is much debate about this proposed co-regency, with different experts considering that there was a lengthy co-regency, a short one, or none at all.

In the fifth year of his reign, Amenhotep IV changed his name to Akhenaten (ꜣḫ-n-jtn, "Effective for the Aten") and moved his capital to Amarna, which he named Akhetaten. During the reign of Akhenaten, the Aten (jtn, the sun disk) became, first, the most prominent deity, and eventually came to be considered the only god.[8] Whether this amounted to true monotheism continues to be the subject of debate within the academic community. Some state that Akhenaten created a monotheism, while others point out that he merely suppressed a dominant solar cult by the assertion of another, while he never completely abandoned several other traditional deities.

Later Egyptians considered this "Amarna Period" an unfortunate aberration. After his death, Akhenaten was succeeded by two short-lived pharaohs, Smenkhkare and Neferneferuaten, of which little is known. In 1334 Akhenaten's son, Tutankhaten, ascended to the throne: shortly after, he restored Egyptian polytheist cult and subsequently changed his name in Tutankhamun, in honor to the Egyptian god Amun.[9] His infant daughters, 317a and 317b mummies, represent the final genetically related generation of the Eighteenth Dynasty.

Ay and Horemheb

editThe last two members of the Eighteenth Dynasty—Ay and Horemheb—became rulers from the ranks of officials in the royal court, although Ay might also have been the maternal uncle of Akhenaten as a fellow descendant of Yuya and Tjuyu.

Ay may have married the widowed Great Royal Wife and young half-sister of Tutankhamun, Ankhesenamun, in order to obtain power; she did not live long afterward. Ay then married Tey, who was originally Nefertiti's wet-nurse.

Ay's reign was short. His successor was Horemheb, a general during Tutankhamun's reign whom the pharaoh may have intended as his successor in case he had no surviving children, which is what came to pass.[10] Horemheb may have taken the throne away from Ay in a coup d'état. Although Ay's son or stepson Nakhtmin was named as his father/stepfather's Crown Prince, Nakhtmin seems to have died during the reign of Ay, leaving the opportunity for Horemheb to claim the throne next.

Horemheb also died without surviving children, having appointed his vizier, Pa-ra-mes-su, as his heir. This vizier ascended the throne in 1292 BC as Ramesses I, and was the first pharaoh of the Nineteenth Dynasty.

This example to the right depicts a man named Ay who achieved the exalted religious positions of Second Prophet of Amun and High Priest of Mut at Thebes. His career flourished during the reign of Tutankhamun, when the statue was made. The cartouches of King Ay, Tutankhamun's successor appearing on the statue, were an attempt by an artisan to "update" the sculpture.[11]

Relations with Nubia

editThe Eighteenth Dynasty empire conquered all of Lower Nubia under Thutmose I.[12] By the reign of Thutmose III, the Egyptians directly controlled Nubia to the Nile river, 4th cataract, with Egyptian influence / tributaries extending beyond this point.[13][14] The Egyptians referred to the area as Kush and it was administered by the Viceroy of Kush. The 18th dynasty obtained Nubian gold, animal skins, ivory, ebony, cattle, and horses, which were of exceptional quality.[12] The Egyptians built temples throughout Nubia. One of the largest and most important temples was dedicated to Amun at Jebel Barkal in the city of Napata. This Temple of Amun was enlarged by later Egyptian and Nubian Pharaohs, such as Taharqa.

-

Nubian Tribute Presented to the King, Tomb of Huy MET DT221112

-

Nubian Prince Heqanefer bringing tribute for King Tutankhamun, 18th dynasty, Tomb of Huy

-

Nubians bringing tribute for King Tutankhamun, Tomb of Huy

Relations with the Near-East

editAfter the end of the Hyksos period of foreign rule, the Eighteenth Dynasty engaged in a vigorous phase of expansionism, conquering vast areas of the Near-East, with especially Pharaoh Thutmose III submitting the "Shasu" Bedouins of northern Canaan, and the land of Retjenu, as far as Syria and Mittani in numerous military campaigns circa 1450 BC.[15][16]

-

Egyptian relief depicting a battle against West Asiatics. Reign of Amenhotep II, Eighteenth Dynasty, c. 1427–1400 BC.

Dating

editRadiocarbon dating suggests that Dynasty XVIII may have started a few years earlier than the conventional date of 1550 BC. The radiocarbon date range for its beginning is 1570–1544 BC, the mean point of which is 1557 BC.[18]

Pharaohs of the 18th Dynasty

editThe pharaohs of Dynasty XVIII ruled for approximately 250 years (c. 1550–1298 BC). The dates and names in the table are taken from Dodson and Hilton.[19] Many of the pharaohs were buried in the Valley of the Kings in Thebes (designated KV). More information can be found on the Theban Mapping Project website.[20] Several diplomatic marriages are known for the New Kingdom. These daughters of foreign kings are often only mentioned in cuneiform texts and are not known from other sources. The marriages were likely to have been a way to confirm good relations between these states.[21]

| Pharaoh | Image | Prenomen (Throne name) | Horus-name | Reign | Burial | Consort(s) | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahmose I / Ahmosis I | Nebpehtire | Aakheperu | 1549–1524 BC | Dra' Abu el-Naga'? | Ahmose-Nefertari Ahmose-Henuttamehu Ahmose-Sitkamose |

||

| Amenhotep I | Djeserkare | Kauwaftau | 1524–1503 BC | Tomb ANB? or KV39? | Ahmose-Meritamon | ||

| Thutmose I | Aakheperkare | Kanakhtmerymaat | 1503–1493 BC | KV20, KV38 | Ahmose Mutnofret |

||

| Thutmose II | Aakheperenre | Kanakhtuserpehty | 1493–1479 BC | KV42? | Hatshepsut Iset |

||

| Hatshepsut | Maatkare | Useretkau | 1479–1458 BC | KV20 | Thutmose II | ||

| Thutmose III | Menkheper(en)re | Kanakhtkhaemwaset | 1479–1425 BC | KV34 | Satiah Merytre-Hatshepsut Nebtu Menhet, Menwi and Merti |

||

| Amenhotep II | Aakheperure | Kanakhtwerpehty | 1427–1397 BC | KV35 | Tiaa | ||

| Thutmose IV | Menkheperure | Kanakhttutkhau | 1397–1388 BC | KV43 | Nefertari Iaret Mutemwiya Daughter of Artatama I of Mitanni |

||

| Amenhotep III | Nebmaatre | Kanakhtkhaemmaat | 1388–1351 BC | KV22 | Tiye Gilukhipa of Mitanni Tadukhipa of Mitanni Sitamun Iset Daughter of Kurigalzu I of Babylon[21] Daughter of Kadashman-Enlil of Babylon[21] Daughter of Tarhundaradu of Arzawa[21] Daughter of the ruler of Ammia[21] |

||

| Amenhotep IV/Akhenaten | Neferkepherure-Waenre | Kanakhtqaishuti (originally) Meryaten (later) |

1351–1334 BC | Royal Tomb of Akhenaten, KV55 (?) | Nefertiti Kiya Tadukhipa of Mitanni Daughter of Šatiya, ruler of Enišasi[21] Meritaten? Meketaten? Ankhesenamun Daughter of Burna-Buriash II, King of Babylon[21] |

||

| Smenkhkare | Ankhkheperure | (unknown) | 1335–1334 BC | KV55 (?) | Meritaten | ||

| Neferneferuaten | Ankhkheperure-Akhet-en-hyes | (unknown) | 1334–1332 BC | Akhenaten? Smenkhkare? |

Usually identified as Queen Nefertiti | ||

| Tutankhamun | Nebkheperure | Kanakhttutmesut | 1332–1323 BC | KV62 | Ankhesenamun | ||

| Ay | Kheperkheperure | Kanakhttjehenkhau | 1323–1319 BC | KV23 | Ankhesenamun? Tey |

||

| Horemheb | Djeserkheperure-Setepenre | Kanakhtsepedsekheru | 1319–1292 BC | KV57 | Mutnedjmet Amenia |

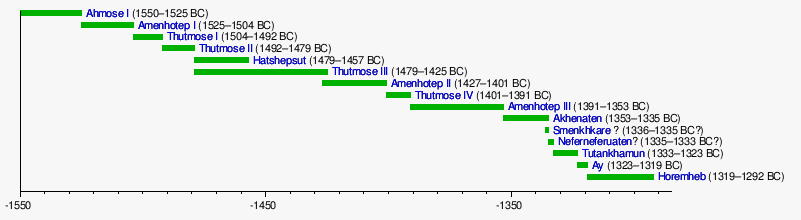

Timeline of the 18th Dynasty

edit

Gallery of images

edit-

Trial piece showing a head of an unknown king in profile. Uraeus on forehead. Limestone relief. 18th Dynasty. From Thebes, Egypt. The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London

-

Amenhotep I gained the throne after his two elder brothers had died. He was the son of Ahmose and Ahmose-Nefertari. He was succeeded by Thutmose I who married his daughter, Ahmose.

-

Amenhotep I with his mother, Ahmose-Nefertari. Both royals are credited with opening a workmen's village at Deir el-Medina. Deir el-Medina housed the artisans and workers of the pharaohs tombs in the Valley of the Kings, from the 18th to 21st dynasties. Amenhotep I and his mother were deified and were the village's principal gods.

-

Thutmose I. A military man, he came to power by marrying the sister of Amenhotep I, or may have been his son to a secondary wife. During his reign, he pushed the borders of Egypt into Nubia and the Levant. He is credited with the starting the building projects in what is now the temple of Karnak.

-

Sketch from temple relief of Thutmose II. Considered a weak ruler, he was married to his sister Hatshepsut. He named Thutmose III, his son as successor, but Thutmose III was too young to rule at his father's death and thus his stepmother Hatshepsut was his regent. Hatshepsut and Thutmose II had a daughter, Neferure.

-

Hatshepsut. Daughter of Thutmose I, she ruled jointly as her stepson Thutmose III's co-regent. She soon took the throne for herself, and declared herself pharaoh. While there were other female rulers and regents before her, she is the only one who used the symbolic beard.

-

Thutmosis III, a military man and member of the Thutmosid royal line is commonly called the "Napoleon of Egypt". His conquests of the Levant brought Egypt's territories and influence to its greatest extent. He also built numerous monuments, most famously his Festival Hall and "botanical garden" at Karnak, and ordered the construction of the city of Napata in Nubia.

-

Thutmose IV.

-

Amenhotep III, whose long reign over Egypt found it at the height of its imperial splendor. He built numerous monuments, including the palace of Malqata, the Colossi of Memnon, and extensive expansions of the Temples of Karnak and Luxor, and has more surviving statutes than any other ancient Egyptian monarch.

-

Queen Nefertiti, possibly the daughter of Ay, married Akhenaten. Her role in daily life at the court soon extended from Great Royal Wife to that of a co-regent. It is also possible that she may have ruled Egypt in her own right as pharaoh Neferneferuaten.

-

Queen Meritaten, was the eldest daughter of Akhenaten and Nefertiti. She was the wife of Smenkhkare. She also may have ruled Egypt in her own right as pharaoh and is one of the possible candidates of being the pharaoh Neferneferuaten.

-

Neferneferure and Neferneferuaten Tasherit. Shown here as children, they were two of six daughters born to Akhenaten and Nefertiti. It is possible that Neferneferuaten Tasherit was the one who may have been her father's co-regent and may have ruled as the female pharaoh, Neferneferuaten.

-

Smenkhkare, was a co-regent of Akhenaten who ruled after his death. It was once believed that Smenkhkare was a male guise of Nefertiti, however, it is accepted that Smenkhkare was a male. He took Meritaten, Queen Nefertiti's daughter as his wife.

-

Tutankhamun, born Tutankhaten, was Akhenaten's son and the successor to Neferneferuaten. As pharaoh, he instigated policies to restore Egypt to its old religion and moved the capital away from Akhetaten.

-

Ay served as a high official to Akhenaten, and a vizier to Tutankhamun. He may have been the father of Nefertiti. After the death of Tutankhamun, Ay laid a claim to the throne by burying him and marrying Tutankhamun's wife Ankhesenamun.

-

After the death of Ay, Horemheb assumed the throne. A commoner, he had served as a military official to both Tutankhamun and Ay. Horemheb instigated a policy of damnatio memoriae, against everyone associated with the Amarna period. With no heir born to him, he appointed his own vizier, Paramessu as his successor.

-

Tiye was the daughter of the court official Yuya. She married Amenhotep III, and became his principal wife. Her knowledge of government helped her gain power in her position and she was soon running affairs of state and foreign affairs for her husband, Amenhotep III and later her son, Akhenaten. She was also Tutankhamun's grandmother.

-

Senenu, High Priest of Amun at Deir El-Baḥri, grinding grain, c. 1352–1292 BC, Limestone, Brooklyn Museum.

-

Beautiful Festival of the Valley (Celebration of the dead in Thebes)

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Wilkinson, Toby (2010). The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt. Random House. ISBN 978-0-679-60429-7.

- ^ Daniel Molinari (2014-09-16), Egypts Lost Queens, archived from the original on 2021-12-21, retrieved 2017-11-14

- ^ Graciela Gestoso Singer, "Ahmose-Nefertari, The Woman in Black". Terrae Antiqvae, January 17, 2011

- ^ Aidan Dodson, Dyan Hilton: pg 122

- ^ O'Connor & Cline 1998, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Aidan Dodson, Dyan Hilton: pg 130

- ^ Kozloff & Bryan 1992, no. 2.

- ^ Dodson, Aidan; Hilton, Dyan (2010). The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson. p. 142. ISBN 978-0-500-28857-3.

- ^ Dodson, Aidan; Hilton, Dyan (2010). The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson. p. 143. ISBN 978-0-500-28857-3.

- ^ Gardiner, Alan (1953). "The Coronation of King Haremhab". Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 39: 13–31.

- ^ "Block Statue of Ay". brooklynmuseum.org. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- ^ a b O'Connor, David (1993). Ancient Nubia: Egypt's Rival in Africa. University of Pennsylvania, USA: University Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. pp. 60–69. ISBN 0924171286.

- ^ Shaw, Ian (2004). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. p. 217.

- ^ "Early History", Helen Chapin Metz, ed., Sudan A Country Study. Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress, 1991.

- ^ Gabriel, Richard A. (2009). Thutmose III: The Military Biography of Egypt's Greatest Warrior King. Potomac Books, Inc. p. 204. ISBN 978-1-59797-373-1.

- ^ Allen, James P. (2000). Middle Egyptian: An Introduction to the Language and Culture of Hieroglyphs. Cambridge University Press. p. 299. ISBN 978-0-521-77483-3.

- ^ "Tomb-painting British Museum". The British Museum.

- ^ Ramsey, C. B.; Dee, M. W.; Rowland, J. M.; Higham, T. F. G.; Harris, S. A.; Brock, F.; Quiles, A.; Wild, E. M.; Marcus, E. S.; Shortland, A. J. (2010). "Radiocarbon-Based Chronology for Dynastic Egypt". Science. 328 (5985): 1554–1557. Bibcode:2010Sci...328.1554R. doi:10.1126/science.1189395. PMID 20558717. S2CID 206526496.

- ^ Aidan Dodson, Dyan Hilton: The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. The American University in Cairo Press, London 2004

- ^ "Sites in the Valley of the Kings". Theban Mapping Project. 2010. Archived from the original on 25 July 2010. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g Grajetzki, Ancient Egyptian Queens: A Hieroglyphic Dictionary, Golden House Publications, London, 2005, ISBN 978-0954721893

Bibliography

edit- O'Connor, David; Cline, Eric (1998). Amenhotep III: Perspectives on His Reign. University of Michigan Press.

- de la Bédoyère, Guy (2023). Pharaohs of the Sun: The Rise and Fall of Tutankhamun's Dynasty. Pegasus Books. ISBN 9781639363063.

- Kozloff, Arielle; Bryan, Betsy (1992). Royal and Divine Statuary in Egypt's Dazzling Sun: Amenhotep III and his World. Cleveland.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Kuhrt, Amélie (1995). The Ancient Near East: c. 3000–330 BC. London: Routledge. ISBN 9780415013536.

External links

edit- Hatshepsut: from Queen to Pharaoh, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF)